Introduction

Behavioural economics has risen to prominence in the last several decades. The Economics behaviourists have proved how an individual’s decision-making may cause people’s choices to deviate from the conventional wisdom based on the assumptions of complete information, constant discount rate, and perfect rationality (Webster et al., 1992). Among those impacts, the first one was discovered as the anchoring impact, which indicates that while people are presented with any initial declared amount indicating a few numerical values, they might function as a reference point (The Effects of Anchoring Bias on Human Behavior, n.d.). It challenged rational models of cognition, social sciences, and economics to show that people’s decisions failed in obeying probability and logic rules.

This way, the participants were told to have written down the last three numbers of their ID card as the “anchoring number” in a bid to establish, among others, which one of the two hypotheses accurately predicts human behaviour and, on the other hand, shows the existence of anchoring. Their next mission was to state the most they would pay for a chocolate bar. The results showed that the anchoring number – the last three digits — strongly predicts people’s willingness to pay. Contrastingly, this contradicts the classic economic model assumption that people make choices based on underlying values which happen to be stable and exact. Assumptions of the behavioural economic model support that people are subject to cognitive biases such as anchoring effect and preferences are built in a gathering process (Rakitta & Wernery, 2021).

Theoretical Basis of the Anchoring Effect

According to Müller (2023), common sense would suggest that conventional thinking ought to suggest judgments are almost invariably derived logically and reasonably. But as the case with the anchoring effect appears, this assumption is seriously questioned. Evidence from choice experiments indicates when the anticipated value model and the conventional economic theory do not always hold (Mariel et al., 2021). By drawing on psychological principles and loosening up the conventional model, behavioural economics explains a few of the most pertinent assumptions made by this model and a few of these outliers (Pidduck et al., 2024). These two models predict WTP outcomes in contradiction if applied to the same good and an “irrelevant” anchor point.

Moreover, forecasting Economic Model with SEM The following, therefore, summarizes the assumptions under which the standard economic model (SEM) is based with regards to rationality and expected maximization of utility:

According to the SM, decision-makers have access to all relevant data, are in a position to weigh all conceivable courses of action (completeness), and can arrive at coherent decisions (transitivity). The fourth element relates to the usefulness term with values, preferences, and choices, assuming that its customers are rationally driven by maximizing their utility and unaffected by moods or additional cognitive biases. Thus, the ordinary consumer does not need an “unrelated” anchoring regarding his WTP for this service as every customer will have adequate knowledge and experience on a regular market commodity. Thus, a successful WTP should reflect precise and uniform consumer preferences for a product that has reached maturation in the market (Morone et al., 2021). Thus, by convention, an anchor price does not influence subsequent WTP values.

Prediction of the Behavioral Economic Model

The most radical concept concerning the anchoring effect negates the conventional paradigm based on which most economic theories rest. It practically challenges the very amount of pure logic and reason upon which human decision-making is assumed to be based. While these assumptions are the base for conventional economic theory and anticipated benefit model yet, as done by the research, it often turns out to be the case that people defy these rules. These behavioural economics try to explain these outliers by bringing in psychological principles and relaxing the basic assumptions of the conventional model.

According to the standard economic theory (SM), common assumptions are that people are fully informed, have full agency to weigh all the available options and make choices within their central beliefs. SM assumes that the purchasers are rational beings who seek only to redress their utility function if it is hampered at any step of availing services. Here, it is assumed that customers are devoid of emotions or other cognitive preconditions in the SM equation utility term. A “greatly insignificant” anchor should not influence WTP as it could be reasonably postulated that, on the contrary, WTP captures actual consumer preference.

According to conventional wisdom, there is no way in which anchor values and the first WTP approximation are related. They underline that the SM theory is based on rationality and predicted utility maximization, summarizing the SM into an equation. However, the anchoring effect is the obstacle of the SM. Behavioural economics deals with this outlier through a psychological approach of reducing the magnitude of the assumptions in the conventional model, which are so stringent, and then filling them with psychological theory.

Additionally, behavioural economists research how cognitive consumers’ biases affect spending habits to decrypt the anchoring effect. The customers hold the initial value they come across during purchasing with high regard, an occurrence referred to as the anchoring effect. On the other hand, behavioural economists state that we are exposed to various cognitive biases. All these biases affect the value we assign to commodities and services under] the anchoring effect.

Conversely, the anchoring effect severely tests the conventional economic paradigm that all people’s choices are purely rational when they have complete relevant information. The incorporation of psychological insights and the relaxation of some of the basic assumptions of the standard model has been understood to have made behavioural economics a field aimed at bringing to light the anomalies found through conventional economics. One of such outliers, the anchoring effect, brings to mind the importance of considering cognitive biases when comprehending customer behaviour.

Experimental Design

For example, an experiment conducted by Ariely et al. (2003) showed that people’s later willingness to pay for various consumable products was influenced by the last two digits of their social insurance number. Anchoring, in which people use a numerical number as a benchmark for future judgments, was supported by this discovery. The present study aimed to verify whether this type of anchoring will influence consumers’ willingness to pay a specific price for a piece of chocolate, with the identified variable being used and with the same experimental design most recently conducted.

In collecting data for this study, the subjects were interviewed such that they would note down the last three numbers of their identification card (ID) and how much they could possibly spend to purchase a chocolate bar. It is essential to remember that personal information or demographics are asked for. The premise was that the numbers on the participant’s IDs would account for differences in their propensity to spend money on the candy bar.

Furthermore, 23 surveys were collected and reviewed in the study to determine if this anchor number positively correlated with paying for a chocolate bar. The target population was limited number-wise, so there will always be concerns about generalization. The researchers’ goal in conducting the statistical analysis was to shed light on how ID anchoring could influence WTP. Subsequently, although the study results are yet to be ascertained, it is most likely to support the finding provided by Möller et al, (2020) that anchoring effects do exist in WTP for a consumable good.

Results

The results indicated that the number of digits in an ID was positively correlated with the WTP for a bar of chocolate. The average WTP for the most minor ID digits in the first quartile from the interquartile ranges was at $4.14 according to the data set, while for the most prominent ID digits in the third quartile, the WTP was $9. The coefficient of Pearson’s correlation has been used to determine whether the anchoring effect exists throughout the research on demonstrating the pattern and magnitude of associations between two variables.

| Subjects | ID | WTP |

| 1. Person 4 | 227 | 2.0 |

| 2. Person | 114 | 1.0 |

| 3. Person 7 | 370 | 2.0 |

| 4. Person 11 | 411 | 4.0 |

| 5. Person | 410 | 4.1 |

| 6. Person | 441 | 6.0 |

| 7. Person 13 | 445 | 7.0 |

| 8. Person | 440 | 6.0 |

| 9. Person | 435 | 6.0 |

| 10. Person 7 | 530 | 6.0 |

| 11. Person 10 | 325 | 3.0 |

| 12. Person | 617 | 6.0 |

| 13. Person 3 | 733 | 7.0 |

| 14. Person 6 | 710 | 0.0 |

| 15. Person 9 | 617 | 6.0 |

| 16. Person 21 | 754 | 9.0 |

| 17. Person 19 | 634 | 0.0 |

| 18. Person | 441 | 6.0 |

| 19. Person 12 | 815 | 14.0 |

| 20. Person 20 | 912 | 8.0 |

| 21. Person | 411 | 4.0 |

| 22. Person 17 | 910 | 8.0 |

| 23. Person 1 | 930 | 9.0 |

| Table 1. Stated WTP about ID -Digits | To test for the presence of the anchoring |

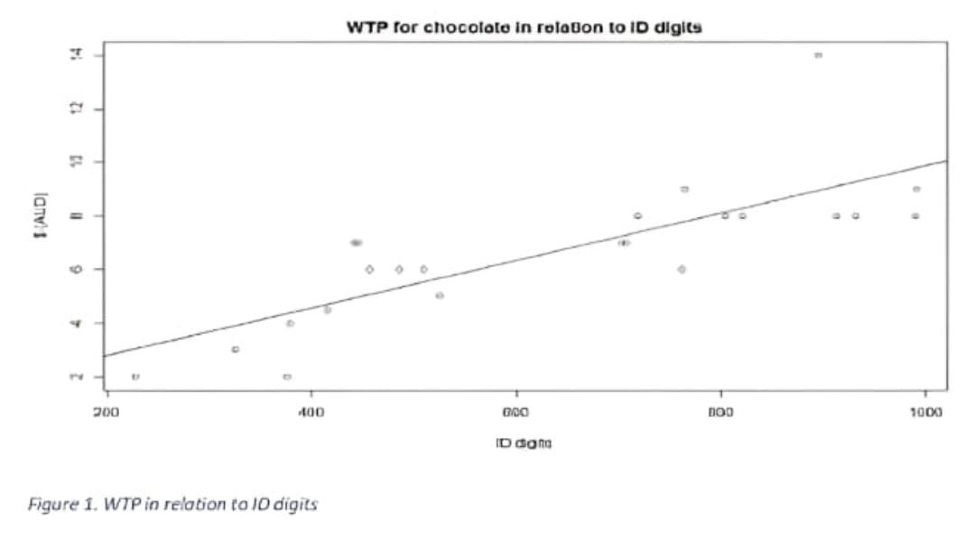

The statistically significant result that rejected the null hypothesis was substantial, and there was a positive correlation between position (ID digit) and WTP. The Pearson correlation score of 0.79 indicates a very positive relationship between the ID digits and the WTP for a piece of chocolate. Figure 1 graphically illustrates the positive relationship between ID digits and WTP. It can be clearly said by observing through Figure 1 that the number of ID digits in the amount of WTP for a bar of chocolate is increasing at a proportional rate. The results indicate that the anchoring effect affected the participants’ value of the chocolate bar. One example of an anchoring effect would relate to the fact that people tend to base their subsequent evaluations (WTP, which is for the chocolate bar) on the first piece of information given to them in numbers, the ID numbers.

Consequently, the results showed an anchoring effect as the WTP is significantly oversized for people with more significant ID digits than their miniature counterparts. A statistically significant positive correlation (t=5.9626, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.5655045,0.9082455]) was established between the ID digits and WTP in the Pearson correlation coefficient applied from the study to prove the relationship. Figure 1 outlines this graphically to see how the ID numbers influenced the participants’ evaluation of the chocolate bar. These results demonstrated how all-important it is to perceive anchorage concerning pricing and customer behaviour programs.

Conclusion

Putting everything together, the statistical results for the given coefficients align with the predictions made under the SH model, supporting the second alternative hypothesis where an anchor number positively relates to WTP. Other factors that could confound refer to differences in what they make of a dollar or a percentage and should be considered in subsequent inquiries of this kind in the future to better interpret the anchoring effect. Income questions to confound a favourable effect on WTP (e.g., Karasmanaki, n.d.) or questions about education levels/cognitive capacity could fall under this category. For instance, Abed et al. (2022) carried out an experiment that proved that the greater the cognitive capacity, the smaller the anchoring effect (though it does not vanish into thin air). A sample size of any future experiment will be given more credit should use a larger sample.

Yet, the experiment results show that people only sometimes follow the recommendations of the conventional economic model. It reflects the nature of behavioural economics to shed light upon the decisions and actions of people. It would call for a scholarly basis for further research based on behavioural models, integrating psychology and psychological elements from philosophy, sociology, economics, anthropology, and econometrics to enhance our understanding.

References

Abed, J., Rayburg, S., Rodwell, J., & Neave, M. (2022). A Review of the Performance and Benefits of Mass Timber as an Alternative to Concrete and Steel for Improving the Sustainability of Structures. Sustainability, 14(9), 5570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095570

Mariel, P., Hoyos, D., Meyerhoff, J., Czajkowski, M., Dekker, T., Glenk, K., Jacobsen, J. B., Liebe, U., Olsen, S. B., Sagebiel, J., & Thiene, M. (2021). Environmental Valuation with Discrete Choice Experiments: Guidance on Design, Implementation and Data Analysis. In library.oapen.org. Springer Nature. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/43295

Möller, J. N., Löder, M. G. J., & Laforsch, C. (2020). Finding Microplastics in Soils: A Review of Analytical Methods. Environmental Science & Technology, 54(4), 2078–2090. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b04618

Morone, P., Caferra, R., D’Adamo, I., Falcone, P. M., Imbert, E., & Morone, A. (2021). Consumer willingness to pay for bio-based products: Do certifications matter? International Journal of Production Economics, 240, 108248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2021.108248

Muhanna, W. A., & Pick, R. A. (1994). Meta-Modelling Concepts and Tools for Model Management: A Systems Approach. Management Science, 40(9), 1093–1123. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.40.9.1093

Müller, J. F. (2023). An Epistemic Account of Populism. Episteme, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/epi.2023.39

Pidduck, R. J., Hechavarría, D., & Patel, A. (2024). Cultural tightness emancipation and venture profitability: An international experience lens. Journal of Business Research, 172, 114363–114363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114363

Rakitta, M., & Wernery, J. (2021). Cognitive Biases in Building Energy Decisions. Sustainability, 13(17), 9960. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179960

The Effects of Anchoring Bias on Human Behavior. (n.d.). SAGU. https://www.sagu.edu/thoughthub/the-affects-of-anchoring-bias-on-human-behavior/

Webster, F. E. (1992). The Changing Role of Marketing in the Corporation. Journal of Marketing, 56(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251983

write

write