Abstract

Keywords: Perinatal depression, postpartum, perinatal well-being, second-time mothers well being

Literature Background

The perinatal phase, defined here as the period between pregnancy and the first year postpartum, is a time of transition characterized by significant changes that may cause worry and stress in some women. Perinatal anxiety and stress are strongly associated through different dimensions caused by a lack of monetary resources, inadequate social support, work/family duties, and pregnancy problems (Bayrampour et al., 2018). Around 17% of women have prenatal anxiety, whereas 84 percent of women experience perinatal stress (Woods et al., 2010). Perinatal anxiety and stress have been linked to an increased risk of premature delivery, low baby birth weight, miscarriage, and preeclampsia. Additionally, maternal behaviors such as alcohol intake, breastfeeding, and smoking are related to perinatal anxiety and stress. Adverse child outcomes include an increased chance of poor cardiovascular health, obesity, poor self-regulation, and challenges with neurodevelopment.

Women’s mental health during pregnancy and the postpartum period is understudied compared to the general public. As a multifaceted concept, “subjective well-being” encompasses both cognitive (such as contentment with one’s life and the ability to perform well) and emotional (such as positive and negative emotions) components that are both unique to each person’s experience and influenced by social norms and values (Organization, 2012). In the past, the phrase subjective well-being has been used interchangeably with the concepts of happiness and flourishing. Emotional well-being, satisfying life, vitality, resilience and self-esteem, positive functioning, and positive functioning are the seven core components of subjective well-being that were developed for use in the 7th round of the European Social Survey (ESS) and used in the context of this paper (supportive relationships, trust, and belonging) (Michaelson et al., 2009).

The connection between subjective well-being and physical health has long been recognized. Although the impact of well-being varies, it has a considerable influence on overall health and may be compared to other health behaviors promoted by public health initiatives, such as regular physical activity and a balanced diet (Michaelson et al., 2009). The relationship between well-being and health is now recognized in health policy, as the World Health Organization and the Department of Health England have both said that well-being is a shared government goal in European Health 2020 strategy (Health, 2010). Women’s emotional well-being is just as vital as their physical health in the eyes of the current maternity care policy, which takes this into account. There has been an increase in screening for mental health issues, but this has to be extended to include a more comprehensive examination of psychological health throughout pregnancy (Midwives, 2012).

Despite this, the word “well-being” is often used in policy and practice with little regard for the psychological concept of subjective well-being, as this study explains. Only a few studies employing a single question on happiness and literature on negative emotions, such as depression, have shown significant results. According to Feyrer et al. (2008), who studied parental happiness before and after the birth of a child, happiness increased in the year before birth and continued through the year after birth but then returned to its pre-child level. First-time parents who were older or more educated were more likely to express delight with the birth of their first child. The responses to happiness in the first two children were enhanced, but those in the third kid were not (Feyrer et al., 2008). In a large European sample, Aassve et al. (2012) showed that parents who had a spouse were generally happier than those who did not have one, but the presence of a partner was closely associated with happiness. When it comes to happiness, these studies utilized basic one-item questionnaires, and parental well-being around delivery is probably more nuanced than previously thought (Alderdice et al., 2017).

Positivity (such as happiness) and negativity (such as sadness) are considered when assessing one’s subjective well-being. Studies of negative affect and mental illness are the primary sources of information on prenatal well-being. Research has continuously emphasized the relevance of subjective well-being in the perinatal period from this opposing viewpoint. It is believed that 15–20 percent of new mothers suffer from sadness and anxiety in the first year after childbirth. According to a study by Paulson & Bazemore (2010) on fathers’ depression, which had a smaller sample size, 10 percent of men reported depression in the first three months after their child was born, increasing to 25 percent in the sixth month or so. Although having a baby is often seen as a joyous occasion for parents, these statistics show that further research is needed to enhance the best subjective well-being of all women and their families throughout pregnancy and the postnatal period.

Studies have been conducted on the well-being of pregnant women. For instance, a novel Well-being in Pregnancy Scale created by Alderdice et al. (2017) was compared to general well-being measures in a sample of 312 pregnant women and showed that the mean Satisfaction with Life Scale score was more significant than those reported in earlier research in a variety of non-pregnant populations. However, the fact that women’s WHO5 Well-being scores were lower than those of the general population shows the complexity of well-being. Two of the five statements, ‘I felt energetic and vigorous’ and ‘I woke up feeling fresh and refreshed,’ had fewer positive answers than the other three, indicating the physical effects of pregnancy rather than overall well-being. For this reason, it is essential to examine whether or not to use the above measure on pregnant women and the necessity of doing more studies into how delivery and the transition to parenting might affect one’s overall health and well-being. As a first step, this article uses a systematic search to gather information on women’s subjective well-being in the postpartum period as a starting point.

Rationale

There is little doubt that the current level of treatment for women’s perinatal mental health needs in the maternity system is inadequate. Pregnant and postpartum women may be under-or over-examined regarding their mental health and emotional well-being. Many women are afraid to discuss their mental health and emotional well-being with healthcare practitioners because of a “culture of silence” surrounding mental health and a focus on the physical health of the mother and baby. Hence, this paper aims to review the existing studies on women’s well-being throughout the perinatal period, emphasizing the first three months after the delivery of a second child.

Objective

The objective of the systematic review is to develop a better understanding of the factors that affect women’s well-being during their perinatal period.

Method

The technique followed a methodical structure, allowing for the incorporation of many forms of literature and methods to aid in comprehending the study issue (Long, French & Brooks, 2020, p. 32).

Review Scope

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Papers that explained well-being – theory, context, well-being as a whole, and perinatal well-being | Studies reviewing mental health |

| Perinatal period as a whole | Studies focusing on the antenatal period only |

| Perinatal or postpartum experiences that may affect well-being or cause problems | Studies reviewing medical issues before the birth of baby |

| Second-time mothers’ experiences | Research on glands and organs in mothers |

| Women over 18years of age | Women under eighteen years |

| Perinatal/postpartum experiences | |

| Factors affecting mothers’ well-being, e.g., complications at birth, birthing method, breastfeeding, low birth weight, and sleep impairment |

Literature Research Process

The literature search was conducted using two distinct methodologies. EBSCOhost was used to conduct an electronic search of psychological databases such as CINAHL Complete, MEDLINE, PsycArticles, PsycInfo, and Psychology and Behavioural Sciences. This search aimed to find important literature using key phrases and the PICO tool (table 1), which is often the most comprehensive search tool (Long, French & Brooks, 2020, p. 34). No further constraints were imposed, owing to the brevity of the study title and objectives. This returned fourteen results. Following that, a manual check of the references was undertaken, deleting duplicates, and then the abstracts and titles of the publications were reviewed, leaving six articles that were read in their entirety (table 2).

Literature search strategy

Table 1: PICO tool electronic search terms.

| P (Patient, Problem or population) | I (Intervention) | C (Comparison, control group or comparator) | O (Outcomes) |

| Mothers | Perinatal | well-being | |

| Mother | well being | ||

| Mum | postnatal | Well-being | |

| Mums | antenatal | Quality of life | |

| parents | postpartum | Wellness | |

| Parent | Health | ||

| women | Positive affect | ||

| woman | life satisfaction | ||

| female | lifesatisfaction | ||

| MOTHERHOOD | QOL | ||

| Marternal | Qol | ||

| AND | AND | ||

| second time mums | Experience | ||

| second time mum | Experiences | ||

| second time mother | experienced | ||

| second time mothers | |||

| second-time parents | |||

| second-time parent | |||

| three months post-birth | |||

| Three months post-birth | |||

| second-time pregnancy | |||

| second-time motherhood | |||

| second time maternal | |||

| SECOND TIME PARENTING |

Quality Assessment

A peer review was undertaken to determine the quality of the research. The framework is intended to assess the general theoretical debate and contributions to specific research fields. It assessed the methodology’s clarity, the sample size chosen, the measurements used, the definitions of well-being and the perinatal period, the study’s design, adherence to protocol, attrition management, and explanation of findings. When peers differed on their ratings, conversations were made to elucidate the reasons, and an agreed-upon rating was established. The included papers varied in their approaches; some were quantitative, while others were qualitative. Therefore, an empirical synthesis was not suitable for this review.

Results

Of the six papers, five met all the criteria for their specific methodology (see Appendix A) (Wadephul, Glover & Jomeen, 2020). All of the studies clearly stated their research questions or aims. The importance of studies’ qualities has been highlighted for unbiased systematic reviews (Khan et al., 1996). However, this review did not aim at meta-analysis but rather to comprehensively gather existing research to understand experiences. Therefore, this study was not excluded from the final synthesis. The result of MMAT was instead used to note the study’s limitations. One study was qualitative, four quantitative studies and only one was classified under mixed-method studies, as shown in the table below.

To assist in determining the acceptability of the research materials, a quality evaluation technique based on CASP (2018) recommendations was used. Notably, the papers were examined for the existence of a clear statement of objectives and the appropriateness of the qualitative technique adopted. Following that, the study evaluated the design and the recruiting approach used to see if they were appropriate for the research’s objectives. Additionally, data obtained throughout the procedure was analyzed to determine the relevance of the study topic to current practice. Additionally, it aided in determining if the link between the study and its participants was sufficiently examined. Having a concise explanation of results and a thorough data analysis procedure allowed for an effective technique of ensuring that all potential clinical outcomes targeted for the research were considered.

One of the publications assessed, Chong and Choi’s (2001), satisfied all of the criteria for the CASP checklist for qualitative research (See Appendix B). As a result, the CASP checklist is an efficient technique for ensuring that the articles examined are suitable for use in similar evaluations. The article had a concise description of acceptable objectives for qualitative research methodologies. Similarly, the study established that the analysis was thorough in establishing the statement of results. Chong and Choi (2001) completed all of the requirements for randomized control trials using the CASP criteria checklist. The article was of good quality, and it included a large number of participants who were all accounted for at the study’s end. Following that, the paper might readily be reproduced in various other scenarios. The remaining five papers satisfied eight of the eleven CASP requirement criteria, classifying them as of medium quality.

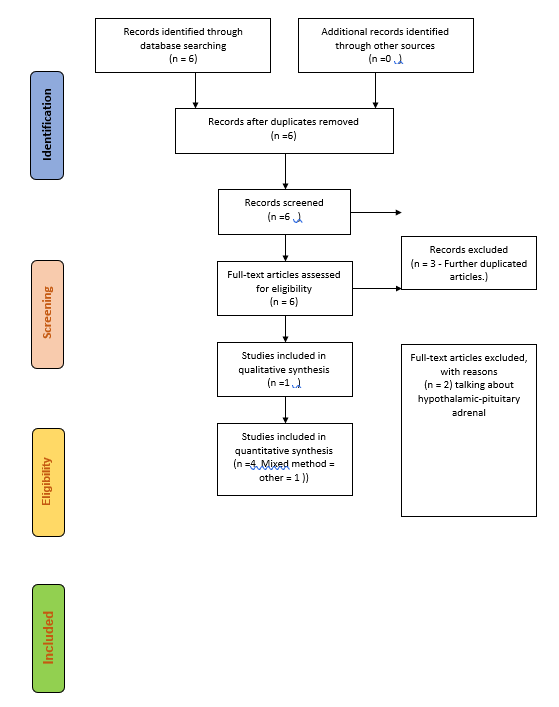

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram

Data and model by Moher, Liberati,Tetzlaff & Altman (2009), reterived from www.prisma-statement.org.

Findings

Four themes of women’s lived well-being experiences during the perinatal period were identified.

Theme One: Understanding Birth Trauma

Childbirth may be a traumatic event for many women, with long-term implications for their physical and mental well-being. According to many women, no matter what sort of delivery they had or what happened after that, their birth experience was traumatic or stressful. Traumatic birth may be an emotional experience in which the mother has extreme emotional responses such as terror and a sense of powerlessness throughout the labor process. Even after the baby is delivered and the physical wounds have healed, women with a history of trauma are more likely to bear the mental scars of delivery for years to come. Two of the six articles reviewed were keen to highlight trauma issues among second-time mothers in dealing with perinatal illnesses and the lack of well-being. Bick et al. (2010) highlighted how perineal trauma has an adverse impact on the new mother’s recovery and psychological well-being. Besides dealing with emotional challenges, perineal trauma affects a mother’s ability to bond with her child. Rather than focus on the baby, the mother is forced to change focus on her health, which most times finds her in excruciating pain. Similarly, Hannah et al. (2002, p. 4) also hinted at how perineal trauma affects the mother. In most instances, the trauma leads to medical complications, which aggravate the mother’s recovery ability. The process is worse for women who undergo delivery through caesarian sections as they must nurse their wounds and take care of the needs of their young ones (Hannah et al., 2002).

Theme Two: Barriers and Frustrations

For most mothers, fear of the unknown after childbirth affects mothers well-being and health (Wigert et al., 2020). Accordingly, those who undergo childbirth for the second time may undergo changes that were not necessarily present during their first birth (Barnes, 2013). Although the theme does not present itself directly in the studies, two out of the six studies illuminated incidences of barriers and frustrations among women, which impact their perinatal cognitive state.

For instance, Lee and Kimberly (2009) record that women described the lack of attention, understanding, and perceived empathy from their husbands as a source of frustration. Chung and Chao (2001) also hinted that frustrations impact the mother’s ability to lead a peaceful life after birth. The need to ensure that perinatal have enough support to help diminish aspects of anxiety provides a unique aspect for the study that ought to be further exploited. Accordingly, mothers who support their spouses will most likely have an easy time taking care of the needs of their children compared to those that lack the same support (Lee and Kimberly, 2001, p. 2). Thus, giving perinatal women peace after birth is an indirect way of offering support in taking care of their young ones.

Theme Three: Training

It was identified that individuals were unaware of the need to train the new mothers on how to take care of their young ones. Accordingly, three of the studies admitted that the fact that mothers enter the task of parenting new babies from different life contexts demands that they ought to undergo the relevant training to enable them to perform their motherly duties (Grace et al., 1993); (Bick et al., 2012) and (Bick et al., 2010). Grace (1993, p 432) hinted that maternal roles constantly evolve. Similarly, Wadephul, Glover, and Jomeen (2020; p. 8) admit that the perinatal role constantly changes. Thus, women must undergo training to help them perform their responsibilities. The fact Because the world is changing regarding research and the development of new products, it is prudent that health experts offer women the leverage to understand the changes that would come about with their daily routines to help realize optimal growth among their children.

Consequently, Bick et al. (2012, p. 7) acknowledge that training should not necessarily be restricted to child care. Women undergo several changes after birth. Thus, the need to impart the relevant skills to enable them to perform their daily routine cannot be ignored. A training package helps in the mitigation of any adverse reactions among women. Training is bound to ensure that women understand the importance of developing effective sleep patterns after birth. Self-care among women after birth is often ignored, thereby exposing individuals to the possibilities of postnatal depression. Chung and Chao (2001) also hint at how important it is for the woman to ensure that she develops a sense of control in becoming a new self. The above studies were identified for inclusion in the review regarding the importance of training for women post-birth.

Bick et al. (2010) also introduce different concept of training. Their research highlights that the need to identify the correct method and procedure to help manage individual issues correctly and align them to facilitate healing is imminent. Bick et al. (2010) identified only 20% of the midwives and 48% of the trainees received training that would be classified as good standards. Equipping experts with the relevant skills stands out as a critical ingredient that would help in enhancing the quality of life led by women after perinatal birth. The need to train women on self-care and take care of their children has an adverse impact on their mental wellness after birth (Grace et al., 1993). Accordingly, the development of programs that seek to empower women to fosters positive development and maintains their sense of control. In other cases, the training can extend to the role of other family members, thereby enabling women to gain a sense of self-love, control, and security.

Theme Four: Supportive Environment

A supportive environment is a critical ingredient in enabling women to deal with the trauma they face after their second children’s birth. All the studies admitted that perinatal women require the support of their partners or family members to help them get through the illnesses they face after birth. Besides struggling with ensuring that their newborn children feed well, it emerges that women also face personal challenges, which they must attend to.

In the study by Bick et al. (2012, p. 5), women who needed emotional support reported 18.9% more incidences of vaginal bleeding compared to those that were emotionally fine. The study also confirmed that perinatal women required support to lead a healthy life after discharge from the hospital. A look at Lee and Kimble’sesults illuminresults The results show that women do not receive the desired help and support after their delivery. Moderate fatigue is allowed. However, when the woman is forced to stay awake, she experiences fatigue due to lack of sleep they are likely to develop depression.

Wadephul et al. (2020, p.2) also emphasized that giving women the support they require to fulfill their role has long-lasting benefits on their perinatal well-being. Thus, the development of effective methods to help women deal with the challenges they face after delivery ensures that women diminish the possibilities of developing depression during the perinatal period.

Discussion

The aim of this literature review was to collate current research and explore the gaps surrounding the factors that affect women’s well-being during their perinatal period. The review was specific to highlighting the understanding of birth trauma. Complicating a traumatic delivery experience are superficial and often well-intentioned remarks such as “oh well, at the very least, you have a happy, healthy kid.” Many women believe they are not entitled to an emotional response to their labor if they have been ‘blessed’ with a healthy baby. This might effectively discredit the woman’s experience and instill the belief that they cannot or should not respond in this manner. Often, women may reflect on other tales about infertility, miscarriage, or unwell newborns and minimize their own experience, as if theirs is unworthy of the tremendous emotions they are experiencing (Watson et al., 2021). This may exacerbate the rehabilitation process after a birth trauma by adding guilt to an already stressful situation. This may also restrict the mother’s inclination to seek treatment or speak about the incident with trustworthy persons in her life, exacerbating any emotional effects. While birth trauma may have a profound effect on a woman and her family, there are several techniques available to assist women in overcoming this event. Perhaps most importantly is understanding that birth, regardless of the result, was a terrible process. Additionally, it might be critical to examine the event’s influence on significant connections with family, spouse, or even infant and how to restore or repair them (Watson et al., 2021). Other critical actions for women after a traumatic delivery experience include being kind to themselves, attempting to alleviate feelings of guilt or self-blame that might impede healing, and speaking with a trusted person capable of providing the necessary emotional support.

Also, the review focused on barriers and frustrations. Barriers to physical activity (P.A.) may be broken down into environmental and individual variables, and research from postpartum women suggests that both elements should be considered before beginning any exercise program. A mother’s circumstances include her income and the number of children she cares for (Albright et al., 2006). Lack of child care and exercise partners and other social support issues, such as unfavorable family attitudes, are additional variables that contribute to a lack of physical activity. On the other hand, environmental influences are beyond the mother’s control and direct experience. Public transportation, neighborhood safety, recreational facilities, and the absence of an informed health care system are all examples of these issues. In several research, it has been reported that these obstacles have the greatest impact on limiting people’s exercise participation.

Postpartum women’s impediments to P.A. must be examined in the context of both personal and environmental factors. Evidence from such studies may be used to promote social support methods such as fitness programs and policy reforms. Taking a strategic approach to P.A. involvement, which is a difficult habit that may be difficult to establish and sustain, can help to increase P.A. participation. A social-ecological model may best characterize these factors (Giles-Corti & Donovan, 2003). This concept necessitates a detailed investigation of the variables influencing P.A. involvement. Women in their reproductive years may benefit from adopting such a framework, which has been proven to be effective in promoting physical activity among Latino women (Larsen et al., 2013).

In addition, the review focused on training as another factor. Being a parent may be a stressful and challenging experience for many people. Nurse facilitators have been the main approach utilized by public health units to provide parent education (prenatal and postnatal) to assist parents during this difficult period. Parent education is described as “A process including the growth of insights, understandings and attitudes and the acquisition of information and skills regarding the development of parents and children and the interactions between them” (Campbell et al., 2004, p. 18). Because of the assumption that increasing information would decrease parental stress, improve parenting knowledge and awareness, and enhance parent-child connections, parent education programs have been implemented. Children’s growth is the ultimate purpose of this instruction (McDermott, 2006). The term “parent education” refers to various activities that are aimed to meet the requirements of a child’s social, psychological, and physical development.

To be effective, new parent education programs need to engage public health nurses who are well-versed in child health issues and parents for whom these programs are intended. Recent studies have begun to challenge whether parent education programs have the reach and effect commensurate with the resources necessary to create and sustain high-quality programs (Gilmer et al., 2016). The main premise of parent education is that a lack of information causes difficulties in parenting and parental discomfort. This assumption is made both implicitly and overtly. Because of this, it is expected that prenatal and postnatal education will assist in alleviating this lack of understanding (Gilmer et al., 2016). Parent education is founded on the concept that when parents are given new information, it will lessen their stress and lead to positive changes in their attitudes and behaviors. Good adjustments in parental behavior can only create a caring atmosphere for children. Even though parent education has the goal of more than just educating parents (e.g., lessening isolation, meeting other parents, and building a relationship of trust with the facilitator), the primary objective of these programs is to provide a curriculum that instructs people on how to be better parents (McDermott, 2006).

Finally, the review focused on a supportive environment as another factor to consider. It is difficult to separate the impacts of genetics, prenatal exposure, and larger social confounding from the specific consequences of postnatal mental illness, which typically begin during or before pregnancy. According to theoretical and empirical evidence, impaired attachment, which is associated with low maternal sensitivity and “parental mentalization,” is a key mechanism for risk transmission to infants (Van Ijzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2019). Externalizing childhood difficulties are linked to attachment problems that are either insecure or disorganized. The importance of a thorough developmental history in prenatal settings is underscored by the fact that disturbed attachment is more strongly linked to mothers’ early trauma experiences (including emotional neglect) than to particular maternal diseases. Positive parenting by a healthy co-parent (father or mother) can protect children from the negative effects of perinatal mental illness but mental illness in both parents and inter-parental conflict are red flags for adverse child outcomes (Barker et al., 2017).

Another important link between maternal depression and children’s externalizing and internalizing disorders has been found in studies of risk factors associated with maternal depression (such as substance misuse, poor social support, interpersonal violence, low educational level, young age). In a study of a large English pregnancy cohort, researchers found that each additional risk factor raised the chances of developing an internalizing or externalizing disorder, highlighting the necessity of multidisciplinary treatment approaches (Howard & Khalifeh, 2020). A recent comprehensive analysis indicated that postnatal depression was linked to higher mortality and hospitalization for infants in the first year of life. There was an association between postnatal depression and one of the leading causes of infant mortality, diarrheal illness. Still, confounders were not adequately addressed in the studies included in this review (Howard & Khalifeh, 2020). Postnatal depression has been linked to infant morbidity, but the evidence for a direct link between the two is scanty. However, perinatal mental disorders are likely to be a marker for high-risk infants, particularly in low- and middle-income countries and high-income countries.

Conclusion

One of the recommendations is that general psychiatric services will always serve women of reproductive age since many of these women will get pregnant, whether on purpose or not, and give birth to children. In general, mental health practitioners need to be taught to “think family” to provide treatment with a life cycle lens, keeping in mind pregnancies and families to do their jobs effectively. Another recommendation is that women require support after birth. Notably, attention is normally paid to first mothers assuming that they are highly vulnerable and hence need the desired support to perform their motherly duties. For second-time mothers, society presumes that they have experience and thus offer little support to enable them to deal with the mental issues that affect them after birth. The possibility of developing mental health challenges is high due to the lack of support and assumption that they can take of themselves after birth. It has a negative impact on their mental health. Thus, based on the emerging four themes, the systematic review confirms that well-being of perinatal women is due to the surroundings and environment of women, all of which affect their abilities to take care of their newborns. Investing in perinatal well-being, especially when backed by a broader evidence base on treatments, is likely to lessen suffering for women and favorably influence their families, even if preconception and public health policies have the largest effect on population health.

Limitations

Several weaknesses stand out in the paper. The perinatal period being investigated in the systematic review spans across three months after the second birth (Bick et al., 2010); (Bick et al., 2012); and (Hannah et al., 2002). Unfortunately, due to the nature of the mental well-being of the patients being assessed, some of the reviews had data looking for the patient’s condition for up to two years of care after the child’s birth (Wadephul, Glover & Jomeen, 2020). Similarly, Grace (1993) spanned its focus across six months, beyond the recommended period. Thus, the studies evaluated the symptoms recorded for women experiencing a second-time pregnancy. The differences in terminologies used may also affect the study’s outcomes due to the long study period. A significant issue of concern when conducting the review is the difference in terminologies, thereby limiting the PICO search process outcomes. While Americans use the terminology fourth trimester, the U.K. terminology for the state is perinatal women. Worse, the Chinese version is secondipara. The differences make it hard to collate similar data on the same topic.

Future Research

Future research may delve into specific themes of the review to help assess how specific factors affect perinatal illnesses among second-time mothers. Particularly, a look at training and the role of a supportive environment in enabling women to deal with perinatal depression will ensure that society is well informed on how to take care of second-time mothers. The study offers a guide to help health workers develop an essential checklist for taking care of women after the birth of their second child to ensure that they do not face perinatal depression.

References

Aassve, A., Goisis, A., & Sironi, M. (2012). Happiness and childbearing across Europe. Social Indicators Research, 108(1), 65–86.

Alderdice, F., McNeill, J., Gargan, P., & Perra, O. (2017). Preliminary evaluation of the Well-being in Pregnancy (WiP) questionnaire. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 38(2), 133–142.

Bayrampour, H., Vinturache, A., Hetherington, E., Lorenzetti, D. L., & Tough, S. (2018). Risk factors for antenatal anxiety: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 36(5), 476–503.

Bick, D. E., Kettle, C., Macdonald, S., Thomas, P. W., Hills, R. K., & Ismail, K. M. (2010). PErineal Assessment and Repair Longitudinal Study (PEARLS): protocol for a matched pair cluster trial. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 10(1), 1-8.

Bick, D., Murrells, T., Weavers, A., Rose, V., Wray, J., & Beake, S. (2012). Revising acute care systems and processes to improve breastfeeding and maternal postnatal health: a pre and post intervention study in one English maternity unit. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 12(1), 1-9.

Chung, F.F., Chao, Y.M. (2001). The lived experience of secondipara in childbirth. Journal of Nursing Research (Taiwan Nurses Association) (J NURS RES), 9(1): 65-75. (11p)

Feyrer, J., Sacerdote, B., & Stern, A. D. (2008). Will the stork return to Europe and Japan? Understanding fertility within developed nations. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(3), 3–22.

Grace, J. T. (1993). Mothers’ self‐reports of parenthood across the first 6 months postpartum. Research in nursing & health, 16(6), 431-439.

Hannah, E., Chalmers, B., Kung, R., Willan, A., Amankwah, K., Cheng, M., … & Gafni, A. (2002). Outcomes at 3 months after planned cesarean vs planned vaginal delivery for breech presentation at term: the international randomized Term Breech Trial. Jama, 287(14), 1822-1831.

Health, D. of. (2010). Healthy lives, healthy people: Our strategy for public health in England (Vol. 7985). The Stationery Office.

Khan, K. S., Daya, S., & Jadad, A. (1996). The importance of quality of primary studies in producing unbiased systematic reviews. Arch Intern Med, 156(6), 661-666.

Lee, S. Y., & Kimble, L. P. (2009). Impaired sleep and well-being in mothers with low-birth-weight infants. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 38(6), 676-685.

Long, H. A., French, D. P., & Brooks, J. M. (2020). Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Research Methods in Medicine & Health Sciences, 1(1), 31-42.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J.,& Altman, D.G.(2009). The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097 www.prisma-statement.org.

Michaelson, J., Abdallah, S., Steuer, N., Thompson, S., Marks, N., Aked, J., Cordon, C., & Potts, R. (2009). National accounts of well-being: Bringing real wealth onto the balance sheet.

Midwives, R. C. of. (2012). Maternal emotional well-being and infant development: A good practice guide for midwives. RCM.

Organization, W. H. (2012). Measurement of and target-setting for well-being: An initiative by the WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Paulson, J. F., & Bazemore, S. D. (2010). Prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers and its association with maternal depression: A meta-analysis. Jama, 303(19), 1961–1969.

Wadephul, F., Glover, L., & Jomeen, J. (2020). Conceptualising women’s perinatal well-being: A systematic review of theoretical discussions. Midwifery, 81, 102598.

Wigert, H., Nilsson, C., Dencker, A., Begley, C., Jangsten, E., Sparud-Lundin, C., . . . Patel, H. (2020). Women’s experiences of fear of childbirth: a metasynthesis of qualitative studies. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Health and Wellbeing, 15(1).

Woods, S. M., Melville, J. L., Guo, Y., Fan, M.-Y., & Gavin, A. (2010). Psychosocial stress during pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 202(1), 61-e1.

write

write