Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, which started at the end of 2019, evolved quickly into a global health crisis of the most significant size among the recent ones. Highly infectious, the pandemic has drastically changed the typical characteristics of nations worldwide, causing health emergencies, economic disruption, and unprecedented transformations in daily life. From healthcare provision and financial instability to mental health consequences, it has been a critical test for all public health systems and a call for a global reexamination of healthcare strategies and capacities. In the United Kingdom, the ramifications of COVID-19 were devastating and complex enough to tear up the healthcare system. The UK’s response to the pandemic has been a journey of ups and downs, mistakes and amendments, showing at the same time the resilience and the weaknesses of the country’s healthcare system. The pandemic brought to the fore the role of healthcare in the national security and overall well-being of society, as well as the areas which need to be strengthened. The main focus of this report is to study the specific challenges and changes in the United Kingdom’s healthcare sector caused by COVID-19. This section will focus on the health system’s adaption to the overwhelming demand, healthcare workers’ roles and implications, and emerging innovations, including telemedicine and digital health services. The report will look at these areas to give a complete picture of the health sector’s answer to a global health problem and its flexibility and future planning.

Literature Review

The once-in-a-century COVID-19 pandemic has put public health systems face to face with the global challenge, which has become one of the most severe healthcare crises in the history of modern healthcare systems. This literature review pulls together facts from academic articles, government documents, and healthcare journals to analyze the UK healthcare system’s answer to the pandemic, emphasizing the initial reaction, resource management, the part played by telehealth and the consequences on healthcare workers and patients.

According to Slater (2021), the response of the United Kingdom government to COVID-19 compared to other nations was a time of constant evolution and pressing adaptation, characterized by both quick and decisive actions and noticeable setbacks. After the very first day, the government received praise for introducing the number one deadly disease as a High-consequence infectious disease, which preorganized the emergency measures for the spread of the disease. This early classification was essential as it attracted the immediate attention of the sector and the public towards the virus’s rapid and destructive course, which became increasingly evident with time. However, this prompt classification contrasts with critiques in academic works and reports that depict the UK’s reluctance to incorporate public health measures such as lockdowns and mass testing, especially compared to other European countries. In this context, critics could say that it contributed to the spread of the virus at its early stages.

Majeed, Maile and Bindman (2020) explained that the healthcare system also came under stress from preparations they had to make. Studies by the National Health Service have shown how testing capacities could not ramp up and how the procurement and risk of shortage of personal protective equipment for healthcare workers were a problem. Besides, the healthcare system was under so much pressure that it identified a significant issue involving the adequacy of a preparedness approach towards pandemics, which also brought emergency measures to the healthcare planning system. The gap between a fast recognition of the virus as a significant risk factor, on the one hand, and a delayed response on the provision of overall protections, on the other hand, is a matter of great concern and has specific suggestions for future health care policy and crisis management, if generalized.

Supady et al. (2021) stated that the pandemic increased current issues and forced acute resource allocation. The study of academic journals and state records gives the readers a clue about how triage protocols and resource allocation operations like ventilators and ICU beds were carried out. What I find striking and also very touching in reading many journals is learning about the ethical dilemmas healthcare providers had to face in deciding which patients to care for during extreme shortages. Along with this, the papers touch upon the measures taken to lessen these problems, for instance, redesigning the hospital space, relocating the non-medical facilities, and seeking overseas supplies. Such adaptation may help maintain some level of service despite shortages in resources, but the fragility of the system will become evident as more limitations are revealed.

Olayiwola et al.(2020) argued that the pandemic facilitated the pace of telehealth service implementation, and the growing trend of teleconsultation and remote diagnosis can testify to this fact. Academia delves into telemedicine controversy, evaluating its efficiency and the problems created for patients and healthcare staff. The fellow with the evident advantages in sustaining the connection and cutting down the infectious risks, the literature also contains drawbacks such as technology barriers and unsuitability for certain kinds of intake. At the same time, some papers assert that the pandemic could also change telehealth from a digital healthcare tool to a more persistent solution in the post-pandemic era.

Billings et al. (2021) stated that The pandemic of COVID-19 exposes the heavy strain on health workers through the literature and illustrates the difficulties encountered in providing care. Research shows the fact that many healthcare professionals have increased workloads that can be a significant cause of their psychological disorders like depression and physical exhaustion. The repeated experience of working under increased stress conditions, coupled with being exposed to emotional anguish from assisting with patient deaths frequently, has affected their emotional stability. And the pressure is rising more and more as the threat of getting infected as well as their own families increases day by day, which causes the anxiety to rise to a new level. Simultaneously, the healthcare sector experiences heightened scrutiny regarding the procedures taken to manage the surgical electives and the allocation of the majority of resources to COVID-19 treatment. Such decisions are often painful, but they may undermine the health of the people who have not yet had COVID. It is these decisions that have brought out the questions of the healthcare system’s resilience and the ability of the system to allocate resources between the pandemic and regular healthcare during the crisis, leading to the call for comprehensive strategies to take care of both pandemic patients and the regular patients who need the care at the same time.

Yamaguchi et al. (2022) showed that the pandemic’s impact on patient care did not end with those affected by the virus but on the health care workers and medical facilities. Studies from medical journals and healthcare analytics showcase deprivation wardrobe routine and elective healthcare services that could result in delays in diagnoses of non-COVID-19 conditions. Such disruption has extended to the whole of society and to people likely to experience detrimental consequences in their health. Moreover, information obtained through patient satisfaction surveys and qualitative studies during the COVID-19 pandemic reflects the changes in the doctor-patient relationships and the perception of the patients about healthcare during the crisis. The literature reveals a multifaceted picture of the healthcare response to COVID-19 in the UK. It sheds light on the adaptability and resilience of the sector, and it also shows the critical areas for planning with more resources. With the pandemic still unfolding, this research provides a timeless document that helps us comprehend the challenges faced and look to the future for healthcare policy and practice.

Analysis of the chosen issues

The COVID-19 pandemic has reminded the entire UK healthcare system about several components that have been brushed aside. Here, we talk about the slow hospital admissions and treatment delays, the impact of telemedicine, the emotional and physical toll on healthcare professionals, and the new health policies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hospital Admissions and Treatment Delays

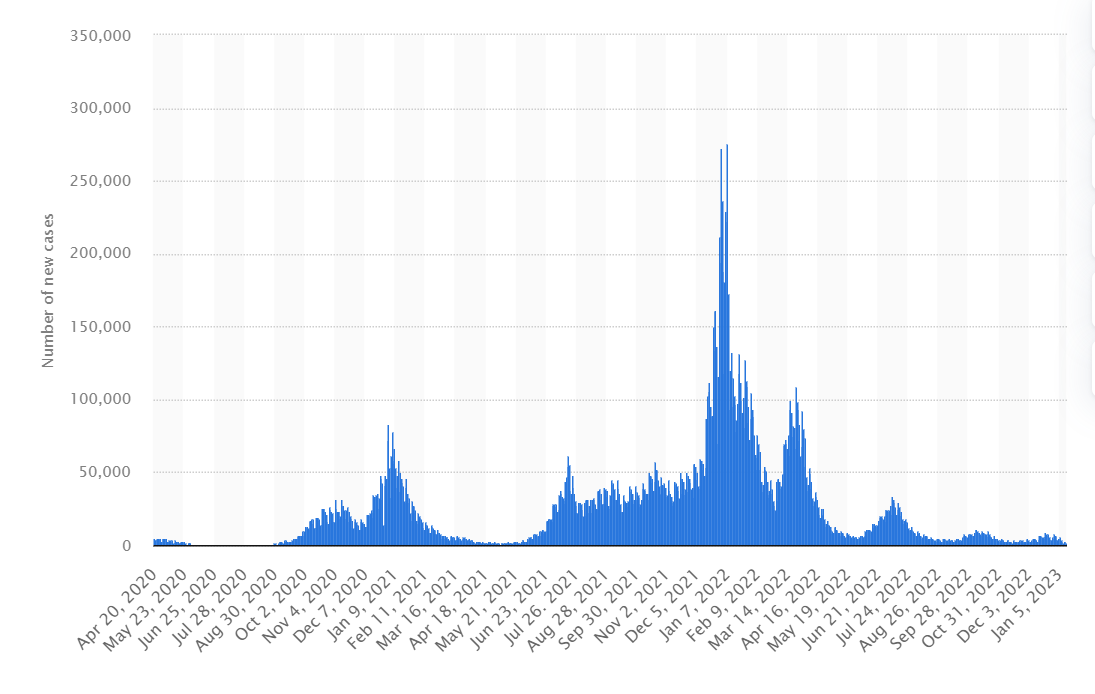

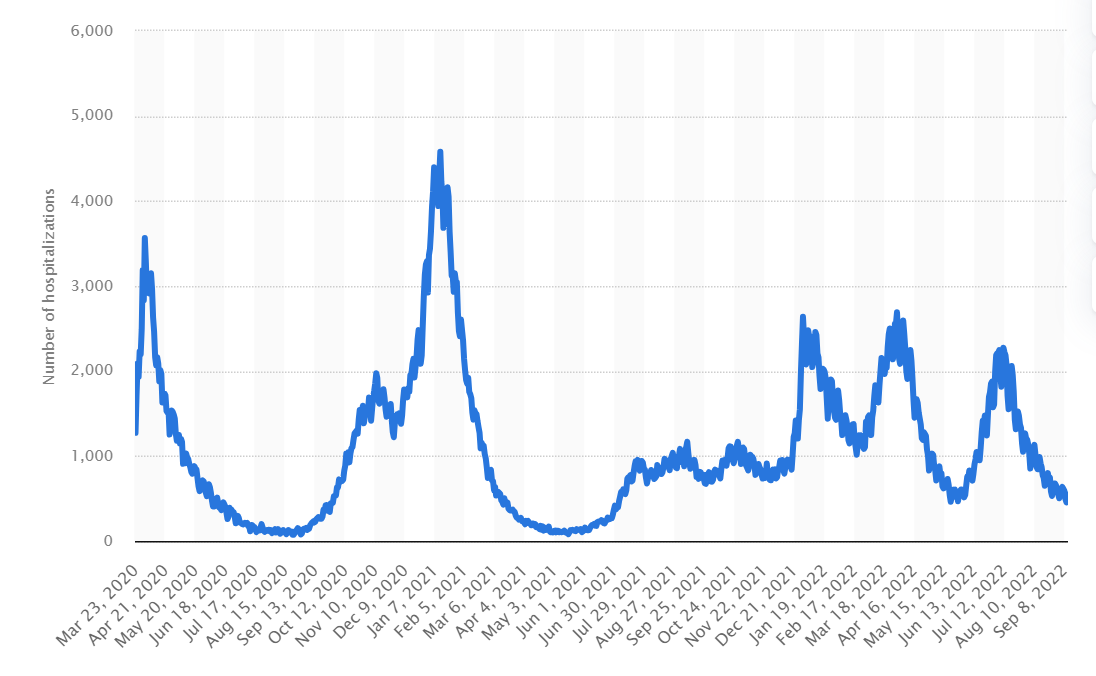

The COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to a never-before-seen increase in UK hospital admissions and has posed a challenge previously unknown to healthcare. The NHS England data unquestionably indicate this rise, especially at the wave crests, by all means posing a threat to healthcare staff. Hospitals that already had a high volume of coronavirus patients had to juggle the care issues for those who did not have it as well (Nourazari et al., 2020). The same journals, like The Lancet or BMJ, issued their studies, all of which revolved around the prolongation or delay in curative or therapeutic procedures for non-COVID patients. The reallocation of staff, beds and tools to Covid 19 care meant that elective operations were postponed or cancelled, and effective chronic disease management took a lot of Work to implement. As a result, the health conditions of the patients needing urgent medical attention probably deteriorated further because of the extended waiting time.

NHS trusts’ reports play an essential role in displaying a clear link between a higher rise in COVID-19 cases and increased waiting times for emergency services, which clearly confirms the pandemic’s impact (Warner et al., 2021). This illustrates the significant challenges in hospitals, where the facilities are already overworked, and staff find themselves in an exhausting situation with no break. Such a crisis brought many issues to the forefront, including the effect of the pandemic on patient care as well as the concerns about the healthcare system’s ability to seize such upheavals. This data highlights the need for adequately designed and flexible healthcare strategies to manage rapid surges in patient numbers during an emergency without compromising a standard medical treatment.

Efficacy of Telemedicine

The pandemic-introduced telemedicine was a significant breakthrough in the medical delivery system, which moved the way care is accessed and provided. It is pronounced that this migration, being reported in digital health journals and NHS reports, represents a significant innovation in the current healthcare background (Galiero et al., 2020). The most influential positive contribution of telemedicine has been the one that helped maintain care continuity, in addition to a drastic decrease in the transmission of COVID-19. Through its remote consultation feature, telemedicine has also bridged the gap caused by government-introduced lockdowns and social distancing protocols such as quarantines. This notably has not been uniform in all medical fields. Success has been significantly higher in mental health services and primary care because consultations do not necessarily mean physical examination.

The participants in these categories gained access to real-time counselling, medication management and continuous support due to virtual capabilities. However, some specialities heavily relying on physical examination and procedures like surgery in an emergency medicine department have faced more hurdles when adjusting to the telehealth healthcare model. However, it is indeed possible to use telemedicine for limited physical examinations, and specific diagnostic tests remotely have raised the risks of misdiagnosis and delayed treatment of more complex medical conditions. Post-service surveys generally reflect a positive response towards telemedicine, appreciating its convenience and accessibility (Brown et al., 2022). Nevertheless, these surveys also indicated something terrible that could be improved, notably missing in physical examinations, which patients feel are critical for correct diagnosis and treatment plans. This partial virtual response shows the weight of a mixed approach for telemedicine applications, combining the strength of remote physician consultations with traditional in-person services when they are required. The target must be to incorporate telemedicine as an additional strategic option in the healthcare system, encouraging accessibility and accuracy while maintaining the quality of healthcare services.

Impact on Healthcare Professionals

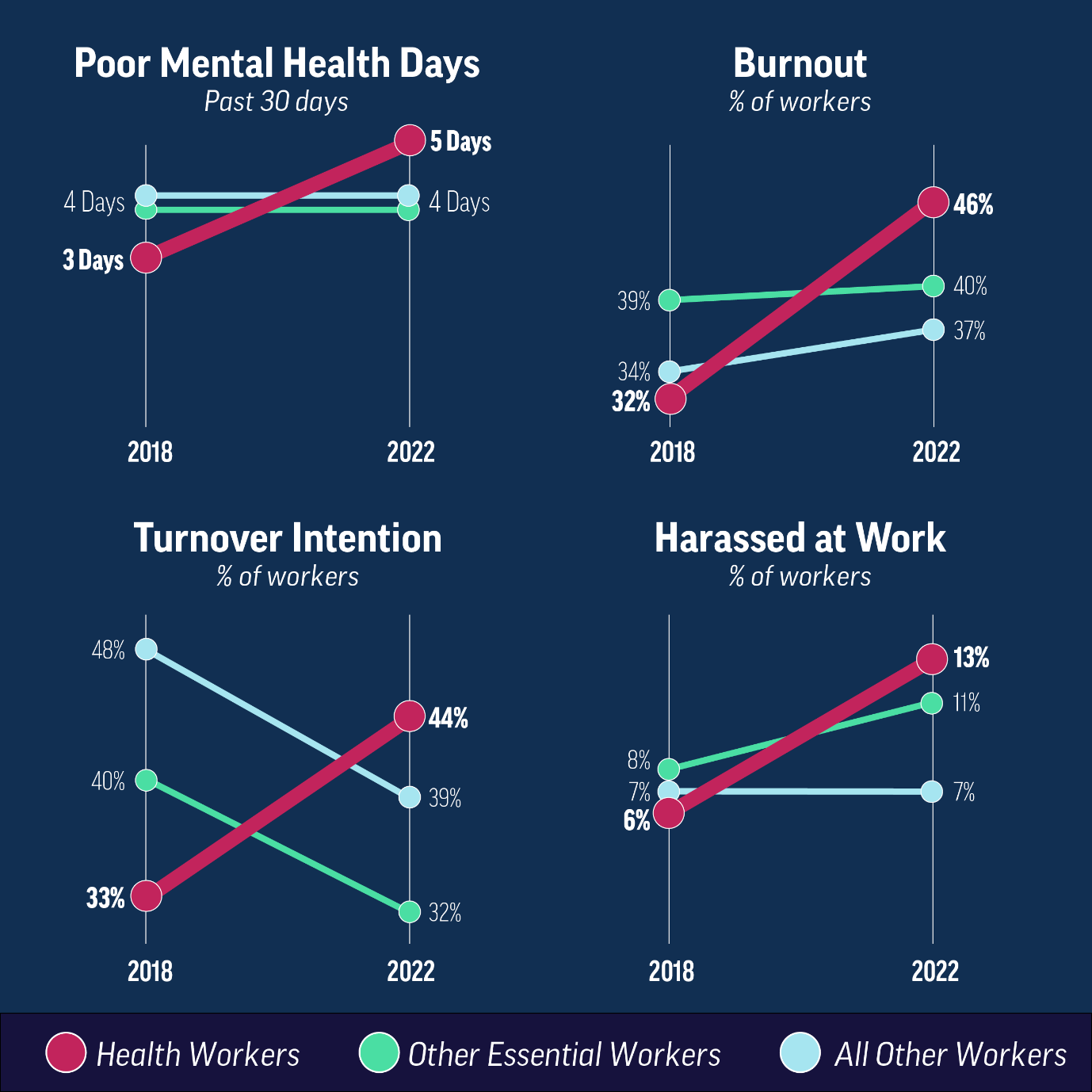

The medical workers’ mental and physical health has dramatically changed and seemed complex and multifaceted during the pandemic. Many trials in psychological journals and workforce surveys have seamlessly demonstrated excessive stress, anxiety and also fatigue among healthcare workers. Mainly, emotional problems, which were caused by long working time, massive deaths among patients and the fear of contracting COVID-19 themselves, had been faced by medical staff. The pandemic, in which insensitivity has continued with endless waves, and the fear of saving lives has placed a significant burden on the mental state of these professionals (Mojca Ramšak, 2024). Meanwhile, physically, healthcare workers have experienced overwhelming exhaustion that is directly tied to doing excessively long shifts and the intense work rhythm amid the COVID pandemic. The increasing physical discomforts and problems arising from the personal protective equipment (PPE) further add to their burden. Which, in turn, demonstrates a crucial concern for comprehensive systemic support mechanisms. Tailor-made mental health services that can provide suitable care and coping methods for healthcare workers are in high demand. Ensuring enough downtime and promoting policies that help one balance Work and life are needed. Without these programmes, the health workers themselves will be in danger, and the sustainability of the healthcare system will be in doubt. In contrast, they ensure that the health professionals working on the frontlines are attended to and supported, giving their patients the best possible care.

Evolution of Healthcare Policies

The track of healthcare policy changes in light of the pandemic is undoubtedly one of the main points of interest. Government statistics, procedures, and health records show a rapid change focused on emergency intervention, resourcing management, and public health messaging (Kessler and Aunger, 2022). The early stages of the pandemic were a time of hasty policymaking. Then, the lockdowns and emergency healthcare facilities were decided. Resource management and distribution were among the essential components of policymaking, including procuring PPE and vaccines. The public health information developed changed with time to replicate the evolving understanding of the virus and balance public health measures with socioeconomic factors. Working on the whole health sector response aspects provides a clearer picture of how the health sector responded to the pandemic. The data reveals the system’s recurring desirable and undesirable elements and becomes a valuable lesson for the health sector in planning better emergency response. Telemedicine adoption, workforce resilience, and volatility will somehow affect healthcare delivery in Britain post-COVID.

Conclusion

The report looks into how COVID-19 has severely affected the UK’s health sector, evident from enormous challenges, instant policy changes, and digital healthcare growth. The pandemic placed high pressure on the healthcare system as more patients required hospital admission, consequently contributing to crowds and treatment delays. Amid these challenges, the healthcare sector demonstrated remarkable resilience, mainly by adapting the telemedicine service quickly, which set the stage for improved present but more accessible healthcare models and services.

Doctors and nurses had to bear physical and emotional burdens among them, raising the priority for their well-being and professional growth. By way of policy, the area underwent drastic changes, from imposing lockdowns to campaigning for vaccinations, which thus illustrated the necessity of agile and evidence-based health policies.

Furthermore, the pandemic is a milestone that has accelerated the transformation in the healthcare learning process. It highlights, in particular, the importance of healthcare systems that can withstand turbulence, sustained financial contributions to technology and infrastructure, and workforce improvements. The experience envisages collaborative policymaking in healthcare to guarantee improved preparedness and response to crises like the recent one.

Recommendation

To address the challenges highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic and improve the UK healthcare sector, several key recommendations are proposed:

Firstly, a significant component of this strategy is strengthening the healthcare infrastructure. Along with other activities, this encompasses increasing hospital capacity to deal with the wave of patients showing up and having a strong supply chain of the only medical supplies. ICU capacities can be improved, and bulk material things, such as personal protective equipment and ventilators, can be built. Hence, we are well prepared for impending health emergencies. Furthermore, the government has to make telemedicine and other digital health technologies more popular through government institutions.

The pandemic has uncovered the power of telehealth in terms of the continuation of treatment and an increase in the reach, accessibility, and efficiency of quality medical services via technology integration. It is vital to think about the digital health technologies training for healthcare staff and the implementation of cybersecurity measures, which will ultimately result in protecting medical records from hackers.

Finally, maintaining the health of healthcare workers is of profound importance. Over the years, the illness has been a vital emphasizer of the state where their mental and physical well-being has been severely impaired. Approaches must be engaged for regular mental screening services, provision of counselling facilities, and creating policies for work-life balance and avoiding burnout. Doctors, nurses, and other medical staff are not just provided with a safe and comfortable working place but are also the foundations that improve the health delivery system. As such, we will not only formulate the changes for healthcare services in Britain but also create the foundation that will support the healthcare system when new hurdles arise, thereby keeping it receptive, patient-centred and resilient.

Reference list

Billings, J., Ching, B.C.F., Gkofa, V., Greene, T. and Bloomfield, M. (2021). Experiences of Frontline Healthcare Workers and Their Views about Support during COVID-19 and Previous Pandemics: a Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. BMC Health Services Research, [online] 21(1). doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06917-z.

Brown, A.D., Kelso, W., Velakoulis, D., Farrand, S. and Stolwyk, R.J. (2022). Understanding Clinician’s Experiences with Implementation of a Younger Onset Dementia Telehealth Service. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 36(4), pp.295–308. doi https://doi.org/10.1177/08919887221141653.

Galiero, R., Pafundi, P.C., Nevola, R., Rinaldi, L., Acierno, C., Caturano, A., Salvatore, T., Adinolfi, L.E., Costagliola, C. and Sasso, F.C. (2020). The Importance of Telemedicine during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Focus on Diabetic Retinopathy. Journal of Diabetes Research, 2020, pp.1–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/9036847.

Kessler, S.E. and Aunger, R. (2022). The evolution of the human healthcare system and implications for understanding our responses to COVID-19. Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, 10(1), pp.87–107. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/emph/eoac004.

Majeed, A., Maile, E.J. and Bindman, A.B. (2020). The primary care response to COVID-19 in England’s National Health Service. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, [online] 113(6), pp.208–210. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076820931452.

Mojca Ramšak (2024). Slovenian COVID-19 discourse in the context of verbal as well as physical violence against medical professionals. Journal of European Studies. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/00472441231221275.

Nourazari, S., Davis, S.R., Granovsky, R., Austin, R., Straff, D.J., Joseph, J.W. and Sanchez, L.D. (2020). Decreased hospital admissions through emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.11.029.

Olayiwola, J.N., Magaña, C., Harmon, A., Nair, S., Esposito, E., Harsh, C., Forrest, L.A. and Wexler, R. (2020). Telehealth as a Bright Spot of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Recommendations From the Virtual Frontlines (‘Frontweb’). JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, [online] 6(2). doi: https://doi.org/10.2196/19045.

Slater, D. (2021). A Systems Analysis of the UK COVID-19 Pandemic Response: Part 2 – Work as imagined vs Work as done. Safety Science, 146(105526), p.105526. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105526.

Supady, A., Curtis, J.R., Abrams, D., Lorusso, R., Bein, T., Boldt, J., Brown, C.E., Duerschmied, D., Metaxa, V. and Brodie, D. (2021). Allocating scarce intensive care resources during the COVID-19 pandemic: practical challenges to theoretical frameworks. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, [online] 0(0). doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30580-4.

Warner, M., Burn, S., Stoye, G., Aylin, P.P., Bottle, A. and Propper, C. (2021). Socioeconomic deprivation and ethnicity inequalities in disruption to NHS hospital admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national observational study. BMJ Quality & Safety, 31(8), p.bmjqs-2021-013942. doi https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2021-013942.

Yamaguchi, S., Okada, A., Sunaga, S., Kurakawa, K.I., Yamauchi, T., Nangaku, M. and Kadowaki, T. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare service use for non-COVID-19 patients in Japan: retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open, [online] 12(4), p.e060390. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060390.

Appendix

Appendix 1: Mental Health Statistics of Healthcare Workers

Appendix 2: COVID-19 Case Numbers Over Time in the UK

Appendix 3: Hospital Admission Rates During COVID-19 in UK

write

write