Introduction

The global overfishing of fisheries has turned into a major issue, compromising both marine biodiversity and the sustainability of fisheries, especially in China. Such a problem leads to a deficit of fish stock and the wreckage of the marine ecosystem that is caused by uncontrolled fishing activities. Governments around the globe acknowledge that to address the issue; they bring in various measures such as taxation and quotas aimed at curbing overfishing and promoting sustainability.

The Necessity of Government Intervention

The overexploitation of fishery resources in China has been the cause of the so-called tragedy of the commons that happens when people act individually in their self-interest to deplete shared resources for the sake of society as a whole (Jimin, 2023).

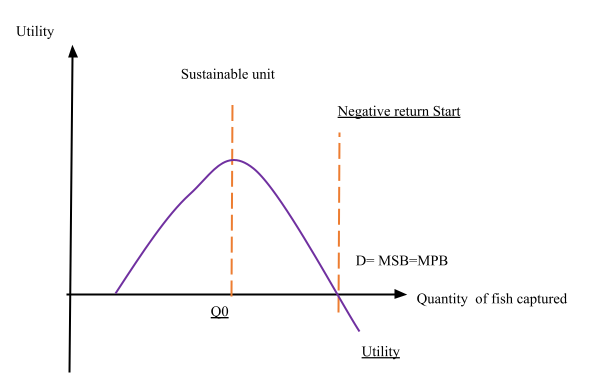

Figure 1Relationship between fish capture and utility

It should be noted that, as shown in Figure 1, oceans are regarded as common property and thus are exploited by everyone. While this open access leads to a case in which all individuals try to maximize their catch without thinking of the long-term consequences, it can be a common situation. Initially, as the endowment of the fish increases, the social utility is enhanced up to sustainable levels where the fish stocks become depleted, the ecosystems are disrupted, and social welfare lowers down.

Analysis of Negative Externalities

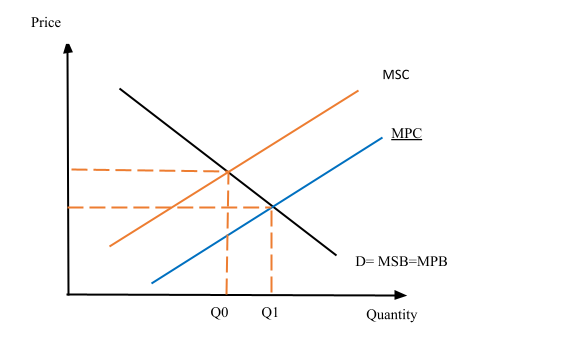

Fish farming not only entails private benefits to fishers but also inevitably leads to environmental shocks, such as negative externalities. These costs range from the destruction of habitats to bycatch of the unintended sorts, as well as pollution from fishing vessels. The marginal social cost (MSC) of fish production is greater than the marginal private cost (MPC) because of these unexpected consequences, as the diagram in Figure 2 shows.

Figure 2 Marginal benefit and marginal cost of catching fish

Consequently, an imbalance is created that ignores the overall social costs of overfishing, giving rise to an imbalance that results in excessive utilization of the fisheries resources. Overstocking of the fisheries causes the quantity to be greater than the MSC; this brings about negative externalities and leads to the exhaustion of natural resources. Market failure arises from the incapability of the market mechanism to allocate resources productively. As a result, a misallocation of goods and services occurs. Concerning overfishing, the tragedy of the commons and negative externalities cause market failure, in which there is no motivation for individual fishers to preserve fish stocks and keep the environmental costs of their actions (Zhang, 2022). Governments must take measures to fix this market failure since the goal is the sustainability of fish resources. Policies like fishing quotas, license regulations, and marine protected areas can also be used to create individual incentives that will help promote societal welfare and the long-term viability of marine ecosystems.

Efforts that the government can take to address the deficit.

To address the problem of over-fishing of aquatic resources, governments should implement efficient tools in the promotion of sustainable fishing practices as well as ecosystem conservation. This may include the use of taxation or the application of quotas.

Taxation as a Measure

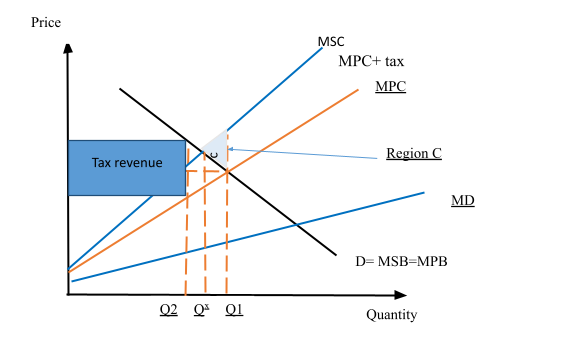

Taxation, indeed, turns out to be a key tool to confront the widespread problem of overfishing, providing an instrument to redefine the economic structure linked to fishing activities. By imposing a tax on the capture of fish, governments put forward a financial admonition that changes the economic reasoning for fishers (Laude, 2023). With this shifting cost structure, actors in the industry are made to reconsider their fishing efforts. As a result, they rethink the way they carry out their catch activities. The government will impose special taxes such that the greater the MSC-MPC discrepancy in the fishing industry, the higher the tax will be imposed. This is indeed a comprehensive approach, which recognizes that marine resources also have other environmental externalities.

Figure 3 Adding a tax on catching fish.

Fundamentally, the fish tax brings about a dramatic shift in the fishing landscape, leading to obvious cuts in the volume of fishing.

As portrayed in Figure 3, such monetary measures will undeniably result in the quantity of fish that will be extracted from the marine life dropping as it will increase the cost of the fish, which will then lead to the demand in the market and availability being decreased. This subsequent decrease in the fishing intensity, thereby, can be regarded as a crucial mechanism that is effective in dealing with the terrible state of overexploitation of fishery resources. Nevertheless, policymakers have the duty to acknowledge the consequences which may appear when tax policy being applied. The main effect of the imposition of taxes will be the demonstration of deadweight loss (DWL), which is evident from the inefficiencies that emanate from the reduced market activity, as displayed by Region C. The overall effect will, however, lead to a reduction in the exploitation of fishery because the quantity supplied will be less than the equilibrium level Q2, therefore depicting reduced exploitation of the resources.

Quotas as a Measure

The quota becomes a colossal regulatory tool in a set of measures to cease the unstoppable over-exploitation present in the fish sectors. This system works by imposing limits on fish volumes harvested during a specified time period.

With the imposition of fishing license limitations, the authorities have a say on the number of fish caught in a certain timespan that may lead to an excessive marine resources exploitation. Deployment of strategic quota system constitutes buffer against the catastrophic drop down of fish stocks by ensuring symbiotic level of harmony among exploitation activities and goals of conservation.

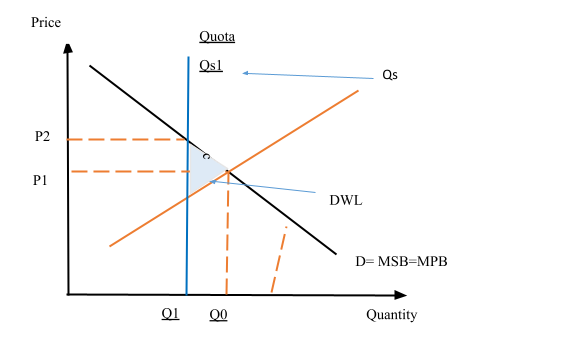

Figure 2 gives a representation of the vital role played by quotas in attaining the desired goal of sustainable utilization of fishery resources. This graphical figure discloses that the introduction of such a regulatory system will allow for the maintenance of a delicate balance between fishing activities and ecosystem conservation in China. In contrast with taxation, which does the major job through the modification of the cost structure, quotas can impose a direct and selective restriction on the volume of fish that can be harvested by limiting the extracted amount to Q1. This may defy the market demand since the supply will be altered by the quotas and move to point Qs1 as the government has imposed it. Through limiting the amount of extraction permitted, quotas give a sophisticated approach to minimizing overfishing which would subsequently enable the partial avoidance of grave consequences of unsupervised exploitation of available resources.

The imposition of quotas is one of the most important instruments for the maintenance of fish stocks levels through the calculation of maximum catch quantities that lead to the conservation of fish resource. Such a proactive mode of resource management testifies about the intention to conserve the marine ecosystems for the generations to come. The legislators should acknowledge the efficiency of quotas in creating a paradigm shift oriented toward ecological extraction in the fishing industry.

Taxation is useful as it decreases fishing efforts, but it also causes deadweight loss and enforcement problems. On the one hand, quotas offer a quantitative and achievable path toward curtailing overfishing, but on the other hand, this approach requires strong monitoring and effective participation from stakeholders. A holistic approach, which incorporates the two types of interventions, could make the most of the opportunities offered by these different types of interventions. By combining taxation to discourage excessive fishing with quotas that directly limit harvest volumes, a powerful model for fisheries sustainability is forged.

Implications of Policies for 3 Nations

In order to respond to the problem of fishery resource overexploitation, different governments across the world have come up will different regulations such as taxation and quotas, to ensure sustainable fishing practices.

Norway

Norway has put a total fisheries management system in place that combines taxation and quotas in order to foster the implementation of environmentally friendly fishing methods. The Norwegian government has determined the total quota for 2024 to be approximately 31,301 tons, which is 15 per cent higher than it was previously (McBride, 2023). Also, there is a salmon farming levy of 25% set up, which is the main objective of the government to fix the environmental issues resulting from aquaculture activities (Furuset and Welling, 2023). The imposed tax here adheres to the theory of taxes, which are used as a cap to cover the externalities and bridge the gap in overfishing.

Based on empirical data, it has been demonstrated that fishing restrictions have been beneficial in achieving the sustainability of stocks even under seasonal changes. Rigorous rules and coping tactics are in place to ensure sustainable use of fish stocks. Individual transferable quotas (ITQs) have made the process of resource allocation more efficient, thus encouraging fishermen to abide by sustainable catch limits. However, the fact that the quota is concentrated among the larger companies might lead to the industry inequalities getting worse.

Iceland

Likewise, Iceland applies a quota-based fisheries management system intertwined with a corresponding tax scheme to control fishing activities more efficiently. The Icelandic quota system allows fishing rights to vessels according to the catch shares level and enables the transactions of quota shares among the fishers. For instance, 1% of the total quota in cod equals 1 kg of the quota (Island.is 2024). Such a system offers fishers incentives to utilize their quota wisely and to invest in sustainable fishing methods.

Research indicates the significant achievements of the quota system in Iceland in the aspect of sustainability of resources and economic enhancement. Nevertheless, two issues arise related to social justice and access to fishing rights (Gunnlaugsson and Saevaldsson 2016). The transferability of quotas opens the door for industry consolidation, which raises eyebrows about monopolistic behaviour and the absence of opportunities for small-scale fishers. Besides, the capacity of taxation to control overfishing is also dependent on the level of enforcement and compliance of governance, which hence needs continuous reforms.

New Zealand

Fishery management in New Zealand is basically based on a system of quota management instead of taxation. The fish stocks have different quotas that are separated into QMAs and are independently administered. Each year, the quota share is allocated across fishers, determining their entitlement to catch certain species within specified levels (Industries, 2020). Although QMS has helped with better stock assessment and reduced discards, challenges still remain regarding the equity of fishing rights allocation and addressing compliance matters. The centralization of quota ownership among a limited set of participants has provoked doubts regarding monopolistic behaviour and the uneven distribution of economic gains (Gibbs 2008). Furthermore, the lack of taxation as one of the regulatory tools reduces the government’s chances of generating funds for fisheries management and conservation activities, which can create a loophole in the regulatory framework.

Comparison and Theoretical Analysis

A comparison of governance in Norway, Iceland, and New Zealand shows that different approaches are needed when designing effective policies to tackle overexploitation. The theoretical analysis highlights the anticipated advantages of taxation and quotas in encouraging sustainability and offsetting any environmental damage. The empirical evidence from these nations suggests, to some extent, that in line with the theoretical framework, positive effects on resource management and economic efficiency can be seen.

Nonetheless, inequalities continue to exist regarding equity allocation of catch quotas, industry concentration and regulatory enforcement. While taxation and quotas are real instruments of fisheries management, their effectiveness largely depends on the context, including the capacity of governance, the structure of the industry, and socioeconomic factors. Norwegian, Icelandic and New Zealand experiences’ insights can help policy-makers design flexible solutions, which will help resource efficiency and ecosystem conservation to survive new challenges.

Conclusion

The management of the fishery resources calls for a multi-pronged strategy which balances economic interests and environmental conservation requirements. Governments can, in this way, regulate fishing activities by taxation and quotas so as to align the personal interests of individuals with the broader social welfare goals. However, despite the challenges of the consolidation of industries and compliance, the lessons learned from Norway, Iceland and New Zealand illustrate that regulatory measures can have positive intended outcomes in promoting sustainable development. Insights taken from these instances will assist officials in coming up with solutions that will help ensure the sustainability of these resources for the benefit of future generations.

Bibliography

Furuset (a_furuset), A. and Welling (d_welling), D. (2023). A salmon farming tax of 25% officially adopted by the Norwegian parliament, ending 8-month saga. [online] IntraFish.com | Latest seafood, aquaculture and fisheries news. Available at: https://www.intrafish.com/salmon/salmon-farming-tax-of-25-officially-adopted-by-norwegian-parliament-ending-8-month-saga/2-1-1459069?zephr_sso_ott=qWWrTL [Accessed 5 Apr. 2024].

Gibbs, M. (2008). The historical development of fisheries in New Zealand with respect to sustainable development principles. The Electronic Journal of Sustainable Development, [online] 4(2), p.1. Available at: https://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/bitstream/handle/10535/2883/THE_HISTORICAL_DEVELOPMENT_OF_FISHERIES_IN_NEW_ZEALAND_WITH_RESPECT_TO_SUSTAINABLE_DEVELOPMENT_PRINCIPLES.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Accessed 1 May 2022].

Gunnlaugsson, S.B. and Saevaldsson, H. (2016). The Icelandic fishing industry: Its development and financial performance under a uniform individual quota system. Marine Policy, 71(6), pp.73–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.05.018.

Industries, M. for P. (2020). Fish Quota Management System | MPI – Ministry for Primary Industries. A New Zealand Government Department. [online] www.mpi.govt.nz. Available at: https://www.mpi.govt.nz/legal/legislation-standards-and-reviews/fisheries-legislation/quota-management-system/#:~:text=or%20tell%20apart. – [Accessed 5 Apr. 2024].

Island. is (2024). Permits to fish | Ísland. is. [online] island.is. Available at: https://island.is/en/permits-to-fish/quota-system.

Jimin, C. (2023). China’s Rampant Illegal Fishing Is Endangering the Environment and the Global Economy. [online] Diálogo Américas. Available at: https://dialogo-americas.com/articles/chinas-rampant-illegal-fishing-is-endangering-the-environment-and-the-global-economy/ [Accessed 5 Apr. 2024].

Laude, Y. (2023). The Chinese fishing industry: a global threat to. [online] Renew Europe. Available at: https://www.reneweuropegroup.eu/news/2023-09-20/the-chinese-fishing-industry-a-global-threat-to-fishing-resources-that-must-be-contained#:~:text=China%20alone%20is%20responsible%20for.

McBride, O. (2023). Norway satisfied to reach Fisheries Agreement with EU and UK for 2024. [online] The Fishing Daily – Irish Fishing Industry News. Available at: https://thefishingdaily.com/latest-news/norway-satisfied-to-reach-fisheries-agreement-with-eu-and-uk-for-2024/#:~:text=About%20the%20agreement&text=The%20parties%20have%20agreed%20on [Accessed 5 Apr. 2024].

Zhang, H. (2022). China’s efforts to reel in overfishing | East Asia Forum. [online] East Asia Forum. Available at: https://eastasiaforum.org/2022/08/03/chinas-efforts-to-reel-in-overfishing/ .

write

write