Description of China’s Double Trap

China’s double trap equilibria is a complicated and complex interaction between institutional quality and earnings levels within the Chinese economic panorama. The People’s Republic of China has witnessed high-quality economic growth and development since 1978, and between 1978 and 2005 witnessed annual growth prices of 10%. These exceptional economic boom and development correlate with adopting market-orientated reforms (Kar et al., 2019). Equally, Chinese economic growth and development correlate to its incessant funding of technological innovation and integration into the worldwide economies on the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) side. As a result, it has leveraged these factors to propel its financial dominance globally, reducing poverty rates for several million citizens (Glawe & Wagner, 2023). The approach also enabled it to acquire a strong position as one of the fastest-developing economies and the second-most largest after the US.

Nevertheless, China has constantly encountered massive debacles amidst this tremendous economic boom due to institutional integrity issues within the political leadership. Institutional integrity, like corruption, opacity, and inconsistency in property rights enforcement, have posed huge impediments to its sustainable improvement (Glawe & Wagner, 2023). They have exacerbated wealth inequality, although it has witnessed massive economic growth and development since the late 1970s. While China is regarded as one of the fastest-growing economies, with the vast emergence of middle-income populations, income disparities are still rampant (Glawe & Wagner, 2023). These exacerbating wealth disparities among citizens of a country witnessing massive economic growth are worrying, necessitating reevaluation of its institutional frameworks.

Additionally, several elements tend to perpetuate a cycle of stagnation and continue widening its income differential. This trend indicates the prevalence of unstable institutional frameworks applied to implement and sustain Chinese economic growth and development. These inept establishments act as huge barriers and impediments to economic expansion, as they not only stifle technological innovation but also increase social discords, particularly amongst low and center-income societies (Glawe & Wagner, 2021). It demonstrates a direct correlation between good/effective governance and the country’s capability to harness its sizeable financial capacity and foster equitable and holistic economic growth and development. Hence, institutional integrity is imperative to sustainable Chinese economic growth and development, including continuing to spur the already achieved economic trajectories (Glawe & Wagner, 2021).

Nevertheless, China has witnessed significant milestones in poverty and income inequality reduction over the past forty years. However, these two challenges (poverty and wealth disparities) have remained ubiquitous among Chinese citizens, necessitating a vast need to understand the role of its institutions (Glawe & Wagner, 2021). As a result, China must break free from the current challenges orchestrating underdevelopment to steer itself toward more resilient and sustainable economic growth and development. It should prioritize reforms fostering enhancing institutional efficacy and transparency (Glawe & Wagner, 2021). Hence, China will witness equitable economic growth, empowering all segments of society to thrive holistically when it adopts the proposed frameworks and contributes to its collective advancements.

Moreover, tackling institutional deficiencies is an important framework for helping China navigate the double trap equilibria, ensuring its strategic economic and improvement goals align with efforts to facilitate sustainable and inclusive monetary empowerment. Its policymakers must concentrate on legislating the current policies to harmonize economic liberalization frameworks (Glawe & Wagner, 2023b). The approach must also foster institutional reforms, as this will facilitate sustainable and fair economic progress. The current institutional deficiencies have not permitted it to distribute resources equitably among citizens, leaving many citizens in poverty. As a result, it must prioritize institutional reforms augmented with transparency measures and the rule of law. China can liberate itself from the current double trap predicaments and unlock its economic prosperity and comprehensive societal development (Glawe & Wagner, 2023b). However, it must undertake some significant reforms within governmental and non-governmental institutions. These frameworks will allow China to compete with developed countries like the US and the European Union. It will cultivate an economic environment embracing diversity and sustainable growth and development. China will also succeed in nurturing and sustaining an all-inclusive society where opportunities are equitable and distributed (Glawe & Wagner, 2023b). Besides, exogenous factors alone are responsible for China’s tremendous economic growth, as institutional arrangements, policy choices, and historical legacies have also contributed to these milestones. These economic equilibria will most likely continue creating self-reinforcing dynamics, where China hardly succeeds in breaking out of low-income traps and sustaining holistic and sustainable economic growth and development (Glawe & Wagner, 2023b). Hence, this challenge will continue entrenching a cycle of stagnation in the Chinese endeavors to spur its economic growth and development.

Application of Theory to China’s Double Trap

The Chinese economic development indicates an intricate interplay of various factors shaping its trajectory in the realm of multiple equilibria theory. Guangdong and Zhejiang are prosperous coastal provinces in China, while Guizhou and Gansu are struggling inland regions. The dichotomy between the prosperous coastal provinces and struggling inland areas illustrates the tapestry of a double trap inside its economic growth and development landscape (Gustafsson & Sai, 2023). Since 1978, Guangdong and Zhejiang have witnessed huge economic boom and development due to strong institutional reforms. Equally, coastal provinces have comparative advantages over other provinces, consisting of strategic geographic places and positioning. Strategic geographic positioning has seen those areas growing strong connectivity to the global markets, improving their universal financial boom and improvement (Gustafsson & Sai, 2023). Consequently, these factors have facilitated their monetary increase and development, spurring growth, attracting overseas and local investments, and boosting industrialization. However, inland regions have not witnessed economic milestones within the coastal provinces. These inland areas still have warfare in numerous demanding situations. They have inadequate infrastructure, excessive literacy levels, and institutional deficiencies, restricting their financial progress (Gustafsson & Sai, 2023). Equally, these regions are marred by factors impeding monetary improvement, while the coastal regions are flourishing economically. Therefore, China’s economic growth and development must foster incisive growth throughout inland and coastal regions to steer it within an extra-balanced and sustainable development trajectory.

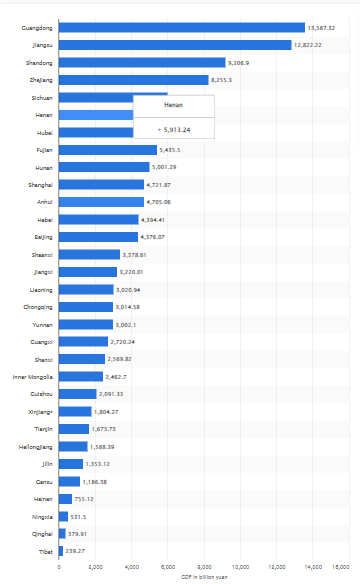

The Chinese urban-rural dichotomy indicates a conundrum with its institutional high exceptional and sticky profits ranges. Its fundamental urban provinces, which include Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, thrive economically on the expenses of different areas, indicating the giant roles of robust and powerful institutional frameworks in championing economic growth and development. The Chinese regions witnessing higher poverty rates indicate a need to reform the prevailing institutional frameworks, as other regions are growing at faster rates than the. While Chinese cities are growing rapidly, the rest of the country is still marred with various challenges, including high unemployment rates, horrible infrastructures and social facilities, and high illiteracy rates (Glawe & Wagner, 2020a). For example, rural provinces like Guizhou and Gansu struggle with deplorable situations like poor infrastructure and inadequate social amenities. They are also struggling with unresolved land tenure disputes and income inequality among populations, which is exceptionally higher than in urban regions. The perpetuated contrasts in economic growth and development between the rural and urban provinces indicated a deep-rooted urban-rural division orchestrated by institutional ineptness (Glawe & Wagner, 2020a). China witnesses a dual-track development trajectory, with people residing in urban regions enjoying massive economic benefits, as those in the rural areas languishing in poverty. For instance, consider Figure (1) highlighting the gross domestic product (GDP) composition by region across China in 2023. The Figure indicates that most urban areas contribute more to the country’s GDP. This indicates the deep-rooted poverty problems in rural regions, unlike in the urban regions. Therefore, enhancing institutional capacities in urban regions could facilitate holistic economic growth and development across the Chinese regions.

Figure 1: The Chinese gross domestic product (GDP) by region (2023).

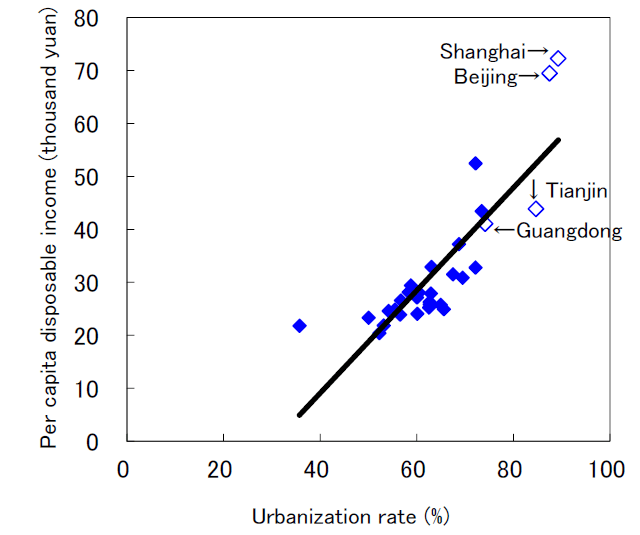

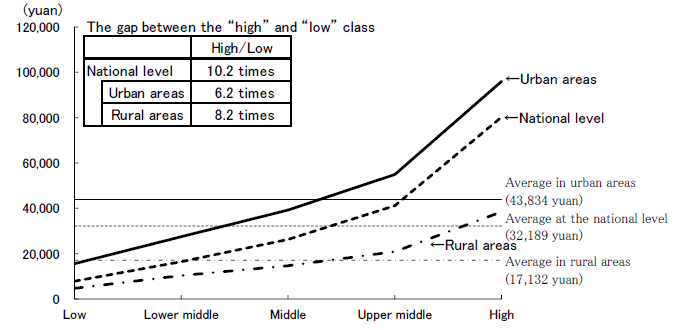

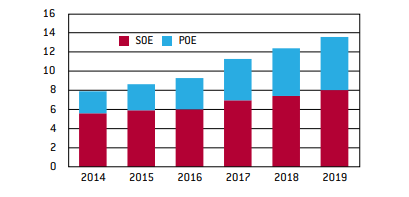

Furthermore, the gap between urban and rural dwellers has remained large across China despite witnessing massive economic growth and development. Currently, the per capita disposable income across the country is approximately 39,218 yuan ($5,511). Unfortunately, per capita disposable income in rural areas is 17,132 yuan, unlike 43,834 in urban areas (Glawe & Wagner, 2020a). It indicates that rural dwellers earn approximately 43% less than urban Chinese despite being in the same country. Figure 2 indicates that urbanized regions, especially urbanized provinces, autonomous regions, and centrally planned municipalities, have higher per capita disposable income than rural regions. Likewise, Figure 3 indicates that in the five classes of income distributions, including high, upper middle, middle, lower middle, and low, the urban populations earn approximately 8.2 times more than rural dwellers. The disparities in the Chinese income distribution between the urban and rural populations indicate laxities within its institutional frameworks. Besides, the income distribution conundrum is evident across companies in this country, with state-owned enterprises (SEOs) having vast income endowment over private enterprises (Figure 4). Figure 4 indicates that state-owned companies have more resources than private companies, suggesting biased government support. SEOs possess strong political ties with the state and, thus, enjoy preferential treatment and access to resources more than privately owned entities (POEs).

Figure 2: Per capita disposable income in rural and urban Chinese regions (2024).

Figure 3: Per capita disposable income by classes across China regions (2024).

>

Figure 4: Chinese listed firms, asset size by ownership (%).

No, given my answer in (b), I do not think that the presence of mechanisms automatically implies the existence of multiple equilibria, as we discussed in the case of the hunger poverty trap. The Chinese double traps indicate an intricate and multifaceted correlation between institutional quality and income levels. It creates a dynamic landscape where several or multiple equilibria, including governmental policies, influence resource allocation, shaping its economic growth and development path. For instance, China boasts of an extraordinary economic boom and development between 1978 and date (Glawe & Wagner, 2020b). Unfortunately, income inequality is still a substantial undertaking amongst rural dwellers, with poverty being more severe in rural regions than in urban areas. These variations correlate to institutional frameworks implemented in city and rural areas to facilitate financial boom and development. Hence, this creates more than one equilibria situation (Glawe & Wagner, 2020b). For instance, provinces like Guangzhou, Beijing, and Shenzhen have witnessed brilliant financial increases and improvements amidst China’s rapid monetary progress. Unfortunately, unlike these towns, inland regions like Guizhou and Gansu still stack in persistent poverty regardless of rapid urbanization and economic boom. This correlation indicates complex developmental demanding situations and constraints across the Chinese areas. Although institutional weaknesses have contributed to its profit distribution disparities, different factors may have also contributed to this task, which aligns with the dynamics of a couple of equilibria.

Furthermore, while China has witnessed exquisite financial increase and development targeting various sectors, this progress now does not obligate the deep-rooted disparities in income distribution and poverty among city and rural divides. The nuanced interaction of institutional pleasant and admission to financial avenues across rural and concrete areas has been attributed to the gaps between the richer coastal provinces and the destitute inland areas (Glawe & Wagner, 2020b). Equally, institutional first-class and admission to financial avenues correlate to disparities between urban regions and rural groups. However, looking into other troubles, apart from regulatory establishments, could divulge elements exacerbating inequality and disparities throughout China (Glawe & Wagner, 2020b). Arguably, the traits of the S-fashioned curve will not align with the dynamics of institutional satisfaction and profit levels, elements believed to be the number one reasons for profit disparities, no matter witnessing wonderful financial boom and improvement. Hence, these factors will not correlate or be accompanied by a couple of equilibria. For example, over time, China has been below persistent profit gaps among rural and concrete populations. It has applied various frameworks to cope with earnings disparities amidst economic reforms, but this problem has endured (Glawe & Wagner, 2020b). It has enforced numerous development frameworks at some stage in regions. However, it has managed to reduce it slightly slower than other advanced international places, indicating the multifaceted nature of these disparities. Therefore, this trouble might emanate from several elements, along with government hints, evolving market dynamics, and deeply ingrained socio-cultural norms.

Finally, the Chinese struggle with numerous developmental demanding conditions is evidence of multiple equilibria because it suggests the intricacy of more than one element in defining a country’s financial improvement course. However, assuming that exceptional governmental elements contributed to this mission leaves some loopholes, necessitating the adoption of possibility clarification and exploring different factors that have continuously exacerbated the Chinese struggles. Factors exacerbating earnings inequality amongst city and rural dwellers, including institutional weaknesses, are also outraged through a couple of equilibria. Historically, China has been acknowledged for its centrally planned economic structures. Unfortunately, this centrally deliberate financial structure keeps affecting its financial and improvement paths. Other factors like shifts in management priorities and political guidelines have also contributed to this mission, as the government spearheads the country’s monetary effects and institutional reforms. However, between the 19870s and early 1980s, China started competing against leading economies worldwide after adopting a mass transformation of its centrally planned economic system into a market-mixed economic system. Notably, these transitions contributed to its development dynamics’ complexities. For example, the entry of multinational corporations from international markets like the US and the European Union contributed to improving coastal cities like Shanghai and Shenzhen, as they found them appealing over Gansu. Therefore, contextualizing the work of institutional integrity issues into the broader socio-economic panorama is critical in establishing the intricate correlations of double trap equilibria in the Chinese economic landscape.

References

Glawe L, Wagner H (2020a). China is in the middle-income trap. China Econ Review, 60(101264), pp. 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2019.01.003

Glawe, L., & Wagner, H. (2020b). The role of institutional quality and human capital for economic growth across Chinese provinces–a dynamic panel data approach. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies, 18(3), 209–227.https://doi.org/10.1080/14765284.2020.1755140

Glawe, L., & Wagner, H. (2021). Convergence, divergence, or multiple steady states? New evidence on the institutional development within the European Union. Journal of Comparative Economics, 49(3), 860–884.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2021.01.006

Glawe, L., & Wagner, H. (2023). New evidence on the human capital dynamics within China: Is there a human capital trap? The Singapore Economic Review, pp. 1–45.https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217590823500145

Glawe, L., & Wagner, H. (2023). The “Double Trap” in China—Multiple Equilibria in Institutions and Income and their Causal Relationship. Open Economies Review, 34(3), 703–757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-022-09693-3

Gustafsson, B., & Sai, D. (2023). China’s urban poor were compared twice as high as the poverty between residents and migrants in 2013 and 2018. China Economic Review, 80, 102012.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2023.102012

Kar, S., Roy, A., & Sen, K. (2019). The double trap: Institutions and economic development. Economic modeling, 76, 243-259.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2018.08.002

write

write