Abstract

The threat to political order, even in the most developed liberal democracies, is serious when violence against politicians ensues. (Krakowski et al., 2022) Shows more than two hundred attempted assassinations of heads of government in the twentieth century. During 1950-2004, a national leader was assassinated in two out of three years (Krakowski et al., 2022). This doctoral research aims to perform a comprehensive analysis of the violence against members, with a specific focus on its manifestations and the nuanced role of gender. This study takes a dual approach by employing a strong literature review and broad analysis of media to provide an extensive insight into violence against politicians from various points. By relying on different theories of political violence, lines from feminist theories and the risks associated with negative campaigning in politics, this research will establish a new paradigm for thinking through this crucial issue.

Research Question and Literature Review

Research Question

How does violence against parliament members manifest itself, and what is the role of gender?

Relationship to Theory

The research is based on the power-threat framework that posits political violence arises from threats to established authorities. Additionally, feminist views are incorporated to assess the challenges that women leadership encounters in politics and communication theories help research on political violence created as a result of negative campaigning.

Objectives

- Identify patterns and manifestations of violence against parliament members.

- Examine the role of gender in incidents of violence against politicians.

- Analyze the impact of negative campaigning on the prevalence of violence.

Hypotheses/Expectations

- Anticipate that certain gender-related factors may contribute to the occurrence and nature of violence.

- Expect that negative campaigning may influence the frequency and intensity of attacks against parliament members.

Literature Review

Theoretical Framework

Political violence is a phenomenon widely discussed in theories. This aspect has been taken up and studied by such people as Bardall et al. (2019) in the power-threat framework where it postulates that violence is a course of action undertaken when one feels threatened over their statuses or powers are under threat. This framework helps understand the forces involved in political violence, shedding light on its dynamics (Kuperberg 2021).

Moreover, theories of gender-based violence have been helpful in elucidation the gendered side of political violence. Krook (2017) adds to this debate by saying that feminist theories point out the issues faced by women politicians who are usually subjected to violence simply because they happen to be female. If one reviews political violence, it must be explored in its entirety to understand the gendered motives of the individuals involved.

Feminist Perspectives on Violence against Women in Politics

Biroli 2018 shows that violence against women in politics is not only a consequence of the rivalry, but it often has the reverse side of misogynism. According to Biroli (2018), male counterparts use political violence against women as a tactic to hold onto their positions of authority since it is based on sexist institutions, beliefs, and behaviours. Domestic violence is viewed as a systemic social activity. When members of specific groups, like the women in this instance, discover that systematic violence is just outside the reach of social imagination and that they may experience it at any time merely by belonging to a particular group (Bjarnegård et al., 2020). This understanding includes physical assaults along with embarrassment, harassment, intimidation and stigmatization. Even though women are differentially affected as well as have gendered experiences that are also determined by colour, class, sexual orientation, generation, as well as nationality, systemic violence targets women simply because they are women. This context highlights the necessity to identify and address political violence in gendered terms.

Building from this, Krook and Sanín (2016) argue that violence against women in politics should be treated as a separate category from other forms of political violence. They contend that the goal of this type of violence is to stop women from participating in society as women, which hurts democracy, gender equality, and human rights. Family members and fellow party members may undermine women’s political campaigns in the name of upholding traditional gender norms; feminist activists may face online harassment, mockery, and threats of rape or murder from anonymous sources; and women may be prevented from voting or forced to vote a certain way by traditional or religious leaders, or even by their husbands (Krook and Sanín, 2017). These dynamics of intimidation and harassment are often combined with threats physical acts of violence, including murder. By undermining the participation of women in specific fields, it seeks to convey a clear and loud message that women should not be collectivized for political activities (Brollo & Troiano 2016; Piscopo, et al. 2016). This point of view contributes to the academic knowledge about this phenomenon, pointing out that women have specific political problems. Understanding the intersectionality of gender, race, and other identity markers will help to understand that violence against women in political roles is a multifaceted problem.

Negative Campaigning and Its Implications

The research on negative campaigning by Krakowski et al. (2021) provides a higher dimension to the literature review analysis. The potential of Aggressive Negative Campaigns for contributing to climate inciting violence against politicians has been realised. The report asserts that such negative campaign approaches may lead to resentment and make public servants more prone to violent attacks and intimidation. The effects of negative campaigning on violence also need to be understood, especially given the growing tendency in modern politics. According to (Brollo & Troiano, 2016), how leaders react to acts of violence against politicians affects public perception. Politicians who take a conciliatory approach in the face of violence are more likely to win support than those who adopt aggressive postures and engage in negative campaigning against their opponents.

Van (2023) argues that the impact of empathy is a consistent result of political killings because people tend to feel sad for the politicians who have died, regardless of their political affiliation. However, if the victim’s politicians are combative and use their grief as an excuse for aggressive political campaigning, these sympathetic concerns might not reach the victim’s broader political party (Krakowski et al., 2022). The public’s worries of a violent escalation and the uncertainty that goes along with it also influence the rally effect: the more people worry that widespread violence may break out, the more probable it is that they will converge on the government. Politicians’ reactions to assassinations, in turn, influence these worries (Krakowski et al., 2022). These factors suggest that politicians who respond aggressively to killings of non-incumbents enrage the public. Fears of violent escalation, as well as uncertainty, are made worse by aggressive responses. This further strengthens the rally effect, which boosts support for the incumbent over the opposition.

Gender and Politics

Common values form the basis of political ideology, some of which centre on the privilege and domination of some groups at the detriment of others. These ideologies offer the uniting themes, objectives, and action plans that enable followers to be organized into a potent combat force (Daniele et al., 2023). Furthermore, the subjugation of women to males in politics, society, the economy, and sexual relations is the most pervasive normative prescription in conflict. Because the most powerful men are the ones who create and manage the political and economic systems that subjugate women and reap the most significant benefits from them, these systems of dominance and subordination continue despite the costs to most men and women (Krook & RestrepoSanín, 2019; Poljak, 2022). High-status males greatly benefit from utilising their influence to maintain their control over women’s ability to procreate and produce offspring, both financially and reproductively (Hadzic & Tavits, 2019). To put it briefly, power imbalances serve to maintain harmful institutions that affect women, children, and most men while also raising the prevalence of political and domestic violence.

The larger body of research on gender and politics sheds light on women’s obstacles while trying to participate in politics. According to research by Kuperberg (2018), patriarchal overtones and cunning on the side of male politicians make it less probable for women in politics to be re-elected, even when they are less corrupt than their male colleagues. Many facets of political violence are heavily impacted by gender. It first helps to make it happen. Second, during times of war, sexual assault results in great suffering (Hadzic & Tavits, 2019). Finally, the involvement and inclusion of women is essential for sustained peacekeeping. Men’s domination over women in many facets of political, social, and economic life is the foundation for the gendered significance of political violence. When family law injustices and marriage market perversions—particularly polygyny—support male dominance hierarchies, political violence is more likely to occur and is more costly for everyone involved (Raney, 2023). This highlights the nuanced ways in which gender prejudice appears in political environments and may foster a violent atmosphere.

Severe cases of beatings and killings of female politicians are occurring worldwide (Krook & RestrepoSanín, 2019). Furthermore, women’s political engagement is restricted by gendered attitudes and beliefs in the day-to-day practice of politics. These include gendered media coverage that trivialises, objectifies, or insults female politicians; a masculine, adversarial style of politics that supports and encourages sexual harassment in legislative chambers; and the exclusion of women from significant committees as well as meetings (Krook & RestrepoSanín 2019; Schneider & Carroll, 2020). Scholars define VAWIP as a continuum that includes severe and everyday abuses (Krook and Restrepo Sanín, 2016).

Analysis

Overview of Incidents

The abilities, diverse viewpoints, and structural and cultural distinctions that female legislators bring help to solve problems creatively and effectively represent the people’s interests. Attacks against female lawmakers are a severe obstacle to society’s advancement. Peace, democracy, and sustainable development depend on women’s active and complete involvement in legislative decision-making, free from restrictions and fear of persecution. Among the incidents that have happened globally are:

Sen. de Lima, a PGA member from the Philippines, is an example. She is a strong fighter for human rights, including a woman who has publicly criticised her administration. As a result, she has faced persecution, mischief, and incarceration on false accusations. The global membership of PGA has repeatedly demanded that President Duterte’s administration free Sen. de Lima from her more than four-year jail sentence. Despite worldwide efforts and outrage, Sen. de Lima is still unlawfully denied her fundamental right to liberty (PGA, 2021).

Following her public admission of being a survivor of sexual assault in July 2020, US lawmaker Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez came under fire from Republican congressman Ted Yoho for using a sexist epithet. Asambleísta Soledad Buendía, a human rights fighter and past head of the PGA National Group in Ecuador, is still living in exile following threats against her life, media attacks, political persecution, and grave breaches of her bodily and mental integrity (PGA, 2021).

In Belarus, one of the biggest obstacles to Alexander Lukashenko’s victory was Ms. Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya’s primary opposition presidential campaign, which took place in July 2020. This time, President Lukashenko specifically targeted female politicians, activists, as well as their families, threatening they would face gender-specific retaliation, including warnings to subject them to sexual assault (PGA, 2021).

The incident in Kerugoya Town, Kenya: Kirinyaga County MP Hon Njeri Maina was attacked following a meet-the_people tour in Kerugoya Town. There are concerns about the security of National Assembly Members when they reach out to their constituencies after this incident that Members of Parliament denounced. Hon. Kimani Ichung’wa, The Leader of the Majority Party, updated Hon. Maina’s status and requested quick action against those who attacked him. The Hon. Opiyo Wandayi, the Leader of the Minority Party, insisted and highlighted that enquiry should go beyond those who attacked to catch financiers as well.

Inter-Parliamentary Union’s Insights: The Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) shows the global violence against women parliamentarians. According to the IPU’s data, women make up slightly more than 26% of parliamentarians around the globe and are facing various barriers like sexism, harassment as well as gender-based assault (IPU, 2022). Gender stereotyping and sexist attitudes significantly affect women MPs’ experiences owing to patriarchal traditions and practices. 82% of the women MPs responding to IPU’s 2016 study reported psychological violence (IPU, 2022). It is necessary to understand the reasons and consequences of violence against women in politics to ensure gender equality as well as remove obstacles to their participation in political life.

Parliamentarians for Global Action: Parliamentarians for Global Action States that sexism and misogyny, combined with democratic backsliding and authoritarian trends, constitute the fertile soil in which violence against women politicians is institutionalized (PGA, 2021). Violence manifests itself in many forms – physical, verbal and sexual abuse; economic crimes like looting or taking people’s resources against their will; child abduction, and robbery with violence attached (PGA, 2021). It can also be seen through harassment of any nature, arbitrary arrest by security forces, and even online attacks. The pandemic has escalated online violence against women parliamentarians, impacting their ability to wield human rights. Cases in the Philippines, the US, Ecuador, El Salvador, Belarus, and Zimbabwe show that such attacks are universal and require international attention for focused efforts to tackle mishaps (PGA, 2021).

Gendered Perspectives

Gender and Political Violence (Krook, 2017) provides research that focuses on gendered barriers to women in politics, which makes them vulnerable to violence because of their gender. Per the global survey by IPU (2022), women are more prone to aggression and harassment than men, particularly those campaigning for the rights of girls.

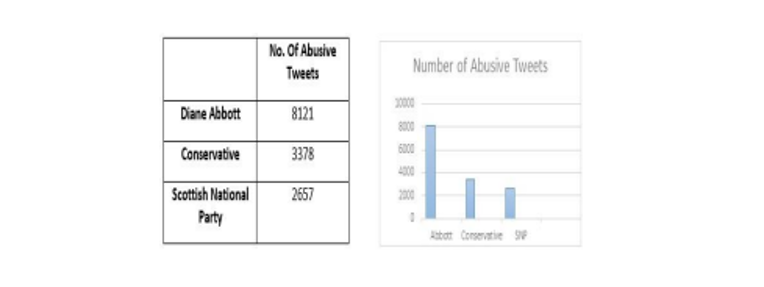

Figure 1: Number of abusive tweets received

Online Violence Against Women Parliamentarians: For instance, Twitter is considered one of the leading platforms for cyber abuse towards women MPs (IPU,2022). There are limitations in identifying abusive content via Automated algorithms, with only 15% accuracy in some cases (IPU,2022).

Negative Campaigning and Violence

The literature indicates that negative campaigning could be associated with the prevalence of violence against politicians (Raney, 2023). Incident analysis with the negative campaigning lens helps provide insight into a larger political picture. Negative campaigning results in a hostile political climate, which could lead to violence against politicians (Raney, 2023). The incidents of negative campaigning reveal the ways this tool is used to influence public sentiments and create favourable conditions for violence.

Social Media Analysis

To consider the changing nature of communication, the study design includes a detailed examination of social media platforms. The information gleaned from Facebook and Twitter is the main topic of this section.

Twitter Analysis: The examples shown highlight how commonplace threats and sexist remarks directed at female politicians are on the internet. According to Harman (2021), abuse on Twitter is a problem that hinders women from participating in politics and has consequences for democracy. In recent years, there has been a particular concern in the UK over violence and harassment directed at female members of parliament (MPs). For instance, MP Anna Soubry has been the target of several tweets threatening to kill her. A Scottish nationalist who was intoxicated has acknowledged insulting SNP MP Joanna Cherry on Twitter. After a whisky-fueled binge last month, Grant Karte sent the Edinburgh South West MP five unsettling internet messages. Nicola Sturgeon is another known victim of assault. As seen in Figure 1 below, she has received several tweets. Amnesty International employed machine learning in September 2017 to quantify and examine online harassment directed at female Members of Parliament who were active on Twitter in the United Kingdom between 1 January and 8 June 2017, emphasising the six weeks preceding the UK General Election. The investigation confirmed how online abuse targets diverse identities and discovered that, on her alone, Diane Abbott, the UK’s debut black female MP and Shadow Home Secretary, got over half (45.14%) of all the abuse directed at female MPs who were active on Twitter during this time. This supports the accounts of the other ladies named in the tweets.

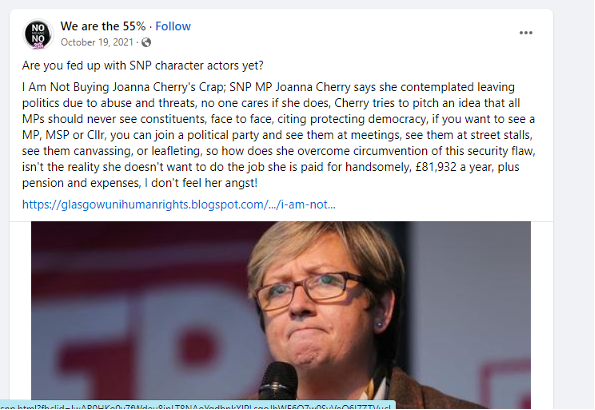

Figure 2: Illustration of violence against women

Facebook Analysis: The analysis highlights how automated algorithms cannot accurately detect inappropriate information on Facebook (Stimson, 2021). For instance, Facebook’s algorithms could only accurately identify 15% of the two million objectionable content violating the site’s policies. Online aggression against women lawmakers has real-world repercussions, including threats, imprisonment, and persecution (PGA, 2021). () reports that MPs have questioned Facebook and Twitter executives on how the social media platforms address online harassment directed at lawmakers. Lawmakers contended that this kind of hate went against democratic values. Figure 2 depicts violence against Joanna Cherry.

Figure 3: Illustration of violence against women

Conclusion

There were several key findings from the investigation that were guided by a research question which sought to understand how violence towards parliament members manifests and what role gender plays in these incidents. The theoretical framework that included a power-threat framework and feminist perspectives offered a solid basis for understanding the motives for political violence and what women in politics go through. The literature review outlined the gendered features of violence against women in politics as a systemic and complex phenomenon. Another critical factor was negative campaigning, which could lead to a hostile political environment favouring violence against politicians.

The research design, which involved a twin strategy of literature review and media analysis, ensured an all-encompassing approach to the study. Global analysis of varied parliamentary incidents bearing differences in political premises was done. Incorporating social media sites such as Twitter and Facebook enabled accurate time analysis of public opinions regarding violence-related cases or incidents. Specific incidents show the dynamics and circumstances of violence against parliament members. Insights from the Inter-Parliamentary Union, Parliamentarians for Global Action and gendered perspectives highlighted the need for global attention in dealing with challenges that women face in politics, such as sexism, harassment and gender-based violence. Social media analysis offered a contemporary view of online violence against women parliamentarians. Twitter and Facebook were found to be considerable spaces of online abuse, affecting women’s political participation as well as democracy itself. This led to limitations of automated algorithms in identifying offensive content on these platforms, highlighting the gulf between online violence and effective ways of curbing it.

References

Bardall, G., Bjarnegård, E., &Piscopo, J. M. (2019). How is political violence gendered? Disentangling motives, forms, and impacts. Political Studies, 68(4), 916-935. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719881812

Biroli, F. (2018). Violence against women and reactions to gender equality in politics. Politics & Gender, 14(4), 681-685. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1743923x18000600

Bjarnegård, E., Håkansson, S., & Zetterberg, P. (2020). Gender and violence against political candidates: Lessons from Sri Lanka. Politics & Gender, 18(1), 33-61. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1743923x20000471

Brollo, F., & Troiano, U. (2016). What happens when a woman wins an election? Evidence from close races in Brazil. Journal of Development Economics, 122, 28-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.04.003

Daniele, G., Dipoppa, G., &Pulejo, M. (2023). Attacking women or their policies? Understanding violence against women in politics. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4587677

Hadzic, D., &Tavits, M. (2019). The gendered effects of violence on political engagement. The Journal of Politics, 81(2), 676-680. https://doi.org/10.1086/701764

Inter-Parliamentary Union. (2016). Sexism, harassment and violence against women parliamentarians. Human Rights Documents Online. https://doi.org/10.1163/2210-7975_hrd-1021-2016006

Inter-Parliamentary Union. (2022, November 24). Violence against women parliamentarians: Causes, effects, solutions. Inter-Parliamentary Union. https://www.ipu.org/news/news-in-brief/2022-11/violence-against-women-parliamentarians-causes-effects-solutions-0

Krakowski, K., Morales, J. S., & Sandu, D. (2022). Violence against politicians, negative campaigning, and public opinion: evidence from Poland. Comparative Political Studies, 55(12), 2086-2118. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/00104140211066211

Krook, M. L. (2017). Violence against women in politics: A Rising Threat to Democracy Worldwide. Journal of Democracy, 28(1), 74-88. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2017.0007

Krook, M. L., & Sanin, J. R. (2016). Violence against Women in Politics: A Defense of the Concept. Política y gobierno, 23(2).

Krook, M. L., &RestrepoSanín, J. (2019). The cost of doing politics? Analyzing violence and harassment against female politicians. Perspectives on Politics, 18(3), 740-755. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1537592719001397

Kuperberg, R. (2018). Intersectional violence against women in politics. Politics & Gender, 14(4), 685-690. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1743923x18000612

Kuperberg, R. (2021). Incongruous and illegitimate: Antisemitic and Islamophobic semiotic violence against women in politics in the United Kingdom. Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict, 9(1), 100-126. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlac.00055.kup

Parliament of Kenya. (2023). 𝐇𝐎𝐔𝐒𝐄 𝐂𝐎𝐍𝐃𝐄𝐌𝐍𝐒 𝐀𝐓𝐓𝐀𝐂𝐊 𝐎𝐍 𝐊𝐈𝐑𝐈𝐍𝐘𝐀𝐆𝐀 𝐂𝐎𝐔𝐍𝐓𝐘 𝐌𝐄𝐌𝐁𝐄𝐑 𝐎𝐅 𝐏𝐀𝐑𝐋𝐈𝐀𝐌𝐄𝐍𝐓. Parliament of Kenya. http://www.parliament.go.ke/node/20645

Parliamentarians for Global Action. (2021, December 21). S.T.O.P. Violence Against Women Parliamentarians. Parliamentarians for Global Action – Mobilizing Legislators as Champions for Human Rights, Democracy and a Sustainable World. https://www.pgaction.org/news/stop-violence-women-parliamentarians.html

Piscopo, J. M. (2016). State Capacity, Criminal Justice, and Political Rights: Rethinking Violence against Women in Politics. Política y gobierno, 23(2), 437-458.

Poljak, Ž. (2022). The role of gender in parliamentary attacks and incivility. Politics and Governance, 10(4). https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v10i4.5718

Raney, T. (2023). Violence against women in politics: An urgent problem the political science community must take seriously. Politics & Gender, 19(3), 938-943. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1743923x23000429

Schneider, P., & Carroll, D. (2020). Conceptualizing more inclusive elections: Violence against women in elections and gendered electoral violence. Building Inclusive Elections, 60-77. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003051954-4

Van der Vegt, I. (2023). Gender Differences in Abuse: The Case of Dutch Politicians on Twitter. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.10769. https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.10769

write

write