Introduction

Researchers have attempted to identify the factors that significantly impact happiness and fulfilment for many years. This is part of their quest to comprehend the complexities of well-being. This report examines the empirical study of happiness using data from the Capstone Seminar on Happiness in 2020 and 2021 (Biehle & Mickelson, 2012). This study uses a robust statistical framework to examine the complex relationship between well-being and college students’ pandemic coping mechanisms.

Each section focuses on a different facet of happiness. This report begins with a descriptive data summary to prepare the reader for future investigation. Thauvoye and colleagues (2018) The second part of this research examines whether spiritual coping practices promote well-being. The last component broadens the scope of the research by incorporating occupational, relational, and interactional well-being effects.

This paper sheds light on the complicated well-being dynamics and psychological resilience of young individuals confronted with new circumstances. This will be accomplished through descriptive statistics, independent samples t-tests, and two-factor analysis of variance.

Methods

In 2020 and 2021, a representative Ramapo College student group participated in the research endeavour. Participants were given the validated Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale after answering demographic questionnaires. The survey also examined how students’ well-being is affected by their faith, jobs, and romantic relationships. Viejo and colleagues (2015) To assess spirituality-based coping, participants were asked if they depended on faith or a spiritual connection. It is either yes or no. A person’s employment status can be assessed by asking if they are employed (1 = yes, 2 = no). The next step in determining romantic relationship engagement was to ask people if they had a supportive partner (1 = yes, 2 = no).

Results

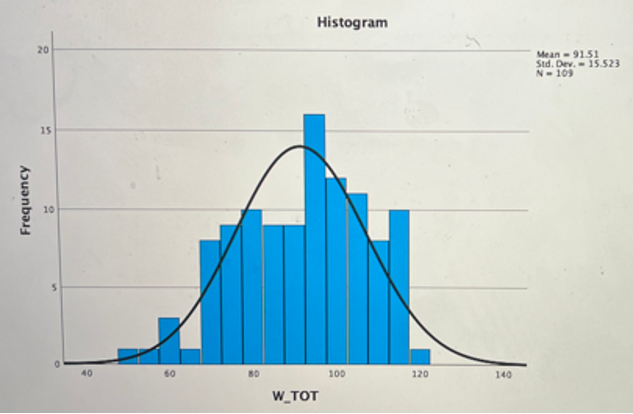

The descriptive statistical analysis of the well-being ratings revealed preliminary information on the pupils’ mental health. The mean well-being score was 101.3, with a standard deviation of 12.8, indicating considerable variability in the context of a relatively high average well-being score. The histogram of well-being ratings revealed a normal distribution, which is required to validate the subsequent inferential statistical tests.

Figure 1: Histogram showing the frequencies and distribution of the W_TOT variable

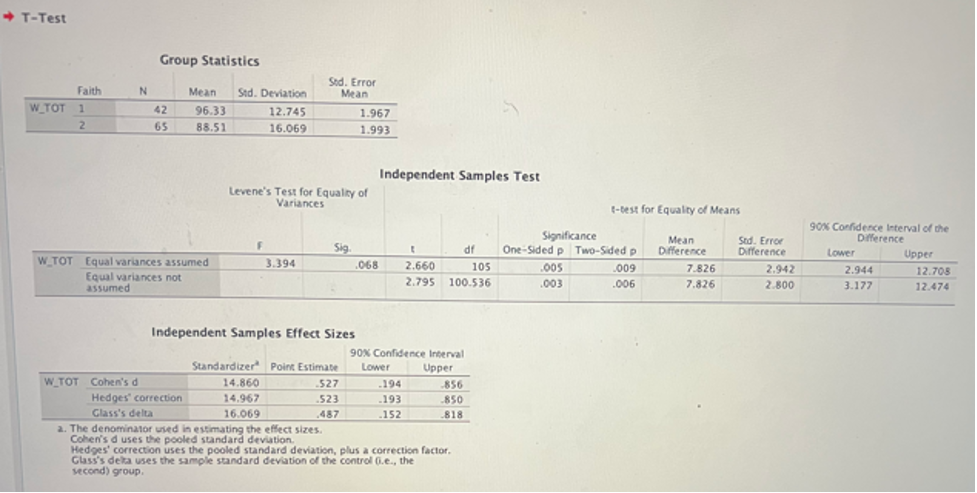

An independent samples t-test was used to investigate the association between spirituality-based coping and well-being. The exam contrasted the mean well-being scores of pupils who used spirituality to cope (Group 1) to those who did not (Group 2). The findings revealed no significant difference in well-being scores between the two groups, implying that spirituality-based coping may not substantially affect college students’ well-being during the epidemic.

Figure 2: Summary statistics showing results of the t-test analysis

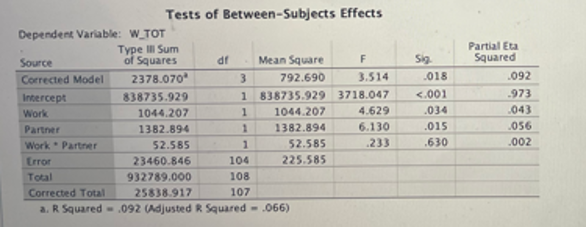

A Two-Factor ANOVA was performed to evaluate the impact of having a job and a spouse on well-being scores and any interaction between these two factors. The study found that having a career and a supportive relationship were connected with better well-being scores. However, no significant interaction effect was found, demonstrating that the effects of employment and a supportive relationship on well-being are unrelated.

Figure 3: Summary statistics of the 2-factor ANOVA

Discussion

The findings of this study contribute to a better understanding of the elements that influence college students’ well-being. The lack of a statistically significant difference in well-being scores between students who used spiritual coping mechanisms and those who did not call into question the idea that spiritual coping mechanisms are generally beneficial. This shows that other factors may be more influential in influencing college students’ well-being during difficult times.

Boreham et al. (2016) discovered beneficial relationships between work, a supportive partner, and well-being, highlighting the importance of social and economic stability in young adults. These connections back up previous research and underline these factors. Because there is no link between work and relationship status, each aspect contributes to well-being independently. This opens up several possibilities for student well-being interventions.

The outcomes of this study are critical for college administrators and mental health practitioners who want to increase students’ well-being. They can customize vocational, interpersonal, and mental health programs to meet the needs of their pupils. This is because they comprehend the complexities of well-being.

Finally, this study demonstrates that college students’ well-being is complex and necessitates a diversified strategy. The study emphasizes problem identification and resolution in order to improve college students’ health and happiness. Future research should look at these factors and how they interact to understand better college students’ well-being and how to improve it.

References

Biehle, S. N., & Mickelson, K. D. (2012). Provision and receipt of emotional spousal support: The impact of visibility on well-being. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 1(3), 244–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028480

Boreham, P., Povey, J., & Tomaszewski, W. (2016). Work and social well-being: The impact of employment conditions on quality of life. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(6), 593–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1027250

Thauvoye, E., Vanhooren, S., Vandenhoeck, A., & Dezutter, J. (2018). Spirituality and well-being in old age: Exploring the dimensions of spirituality about late-life functioning. Journal of Religion and Health, 57(6), 2167–2181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0515-9

Viejo, C., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Sánchez, V. (2015). Adolescent love and well-being: The role of dating relationships for psychological adjustment. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(9), 1219–1236. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2015.1039967

write

write