1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

In the contemporary market, there are several companies competing to survive and the inundation of companies in the market has saturated the feasibility of brand differentiation which is based on traditional attributes such as quality and price (Adiwijaya and Fauzan, 2012). The pressure for brands to differentiate themselves is more intense than ever, and many corporations are facing new consumer demands for them to be fully ethical in their corporate conduct, something which surpasses their own commercial interests (Brink et al., 2006). As a result, finding a cause that appeals to customers is increasingly believed as a method of strategically obtaining bot success and differentiation (Grad, 2004). In order to do this, a new marketing activity called cause-related marketing (CRM) which highlights a company’s social responsibility is becoming increasingly employed by many firms.

1.1.1 Cause-Related Marketing

It is widely accepted that Cause-related Marketing (CRM) was inaugurated in the 1980s when the American Express devised a scheme which gave one cent to a Statue of Liberty restoration project when the company’ credit card was used credit card. There was an outlay of 6 million pounds on this campaign, with one million pounds actually raised for the project and their card usage increased by a considerable 28%, which means the campaign was well worth conducting (Tanen et al. 1999, as cited in Berglind and Nakata 2005). Dupree (2000) explains the rationale behind CRM becoming more popular: consumers are also becoming more social conscious. Compared to empirical markets, consumers are having an increased focus on price and quality and social welfare and happiness (Belk, 1985). To satisfy this demand, many firms are now active users and proponents of the concept of cause-related marketing (CRM), which could allow them to meet the triumvirate of raising their standing and reputation among consumers, create a brand image which consumers can develop an affinity with and also ultimately increase their income and revenue. There have been numerous definitions of CRM, although one notable one which has been accepted is Varadarajan and Menon’s (1988) who define it definitively as:

“The process of formulating and implementing marketing activities that are characterized by an offer from the firm to contribute a specified amount to a designated cause when customers engage in revenue-providing exchanges that satisfy organizational and individual objectives“

(Varadarajan and Menon, 1988, p.80)

Essentially, CRM normally occurs when a firm pledges to make a donation to a charitable or philanthropic cause in proportion to each purchase of goods from their company. There is certainly a similar association between cause-related marketing and corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Kim et al., 2005). Here, when connecting the brand with corporate social responsibility (CSR), CRM could really set a company apart from its competitors and give it added credence (Brammer and Millington, 2006; Du et al., 2007, as cited in Bigne’-Alcaniz, et al., 2009). CRM is used heavily in CSR and ensures that altruistic actions which are undertaken, are heavily connected to improving the long-term performance of organisations (Singh et al., 2009; Hammad et al., 2014). In fact, the use of CRM as a new marketing platform has already been progressively employed by many companies that are of the disposition that modern consumers increasingly value the support of social causes of corporates (Cone, Feldman, and Dasilva, 2003, as cited in Youn and Kim, 2008). Perhaps a notable example of this is the One-for-One campaign from shoes brand TOMS which stipulates that the for every pair of shoes purchased of the company, they will match this by purchasing new shoes for a child in need, which increases both the company’s social standing and its reputation.

1.2. Gaps in the Literature

However, CRM does not seem to appeal all consumers equally and it is a difficult prospect to appreciate what the clear consequences of it are. Several studies have already come to the realisation that CRM might link with consumers’ perception or attitude (Sen and Bhattacharya, 2001). Nevertheless, there is a paucity of literature which solely focuses on analysing influence on CRM on consumer purchase intention and brand loyalty (Barone et al., 2000). Moreover, there have also not been a sufficient amount of studies which determine a comprehensive and clear linkage between antecedents of successful CRM and its outcomes in consumption. Fundamentally, information about antecedents of consumer traits and outcomes in real consumption such as consumer perception after CRM experience is scarce. This illustrates succinctly that there is a gap in the research which will be addressed by this study as it focuses on identifying antecedents and outcomes of CRM.

1.3. Research Objective

To completely clarify the mandate and scope of this study, a clear statement of the objectives of this research needs to be provided. The main objective of this paper is to identify and examine the factors of consumer antecedents and outcomes of cause-related marketing. The set of antecedents relates to personal characteristics of the consumer that effect how they respond to CRM campaigns (Hammad et al., 2014), something which is considered as a key evaluative instrument for understanding determinants of CRM. Next, this study will investigate to what extent CRM contributes to positive outcomes and whether it really influence consumer attitude, perception and brand loyalty. According to the IEG Sponsorship report (2014), marketers invested $11 billion on cause related marketing in 2005 and $1.34 billion in 2006, an extensive financial outlay which indicates that firms perceive there to be significant benefit to performing CRM. This research could have the advantage of contributing to the pool of knowledge available on CRM and allow the companies interested in CRM to produce more effective marketing activities as the research aims to inform them what antecedents should be considered and the real impact of CRM on outcomes which have been prevalent in a battery of other studies. Data collection methods included an online survey and SPSS; correlation, bivariate regression and multiple regression tests were conducted to analyse the data and draw valid conclusions from it.

1.4. Contribution of the study

This study will attempt to clarify which antecedents positively affect CRM and the outcomes that are influenced by CRM, as there is insufficient previous research on consumer characteristic drivers and specific outcomes of CRM. This study addresses this gap in research and is exploratory and innovative to some degree as no previous research has been conducted into this specific topic. The study also has the advantage of providing initial information which can be used to supplement and inform the composition of further studies by scholars and be a point of reference for them. It is noteworthy that merely increasing the budget of investment in CRM does not guarantee satisfactory changes in consumers or results (Green and Peloza, 2011). Realising which types of consumers are more favourable to CRM prior to using it is undoubtedly important not only for segmentation but also for strategic contents of CRM campaign. Furthermore, a clear understanding of outcomes of CRM is also significant so that corporations can acknowledge the significance of the results they are expecting. The outcomes of this research could be applicable to many companies and allow them to try to comprehend and satisfy highly demanding consumers through CRM campaigns.

1.5. Structure of this study

Ultimately, this study will evaluate the antecedents and outcomes of CRM in consumption by analysing previous authoritative academic literature on factors influencing successful CRM and consequences of CRM in the literature review portion of this dissertation. Furthermore, it will assess the efficacy of methods used in this study with the research design, operationalisation of constructs and sampling process design all under consideration. The sampling and research methodology will be communicated which distributes questionnaires to 120 respondents and analyses the findings using the widely-used statistical program, SPSS.

It will cross-reference the previous literature against the primary research findings to evaluate the hypotheses used in this dissertation, which should provide an accurate indicator of the alignment between theory (literature) and practice (the outcomes of this research project). The study will address the implications of certain recurrent findings and also assess the strengths and limitations of this study impartially.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Introduction

This chapter has four main objectives: firstly, it will examine and appraise the various construal’s and definitions of cause-related marketing and the research which is relevant to it; secondly, it will examine historical literature and studies to gain an more in-depth understanding of CRM; thirdly it will both identify and evaluate drivers (i.e. antecedents) of CRM which the literature refers to, finally, it will examine how successful CRM affects consumers.

2.1.1. Concept of CRM

Cui et al. (2003 p. 310) refers to CRM as “a general alliance between businesses and non-profit causes that provide resources and funding to address social issues and business marketing objectives.” Basically, the main function of CRM activities is based on the premise of affecting people’s emotions so that they purchase the company’s goods and ‘buy into’ the brand attitude and ethos (Tsai, 2009). As expressed above, CRM is emotionally-motivated and appeals to a person’s need to give and the positives of people that do (Polonsky and Speed, 2007). Unlike CSR, CRM is a transaction-based marketing tool that elucidates that if consumers purchase a product from a for-profit company, then the company will subsequently donate a proportion of the product’s purchase price to the associated charitable cause (Davidson, 1997). The rationale behind this is that it appeals to consumers who want to change society through their purchasing behaviour (Bronn and Vrioni, 2001).

2.2 Theories in CRM

The intention of this chapter is to supplement the content of the study with a sound understanding of the theoretical tenets of Cause-Related Marketing. This chapter will commence with the attribution theory which is the basic theoretical framework in CRM. The concept of exchange theory in marketing field will also be discussed and lead the chapter forward to the description of CRM. Both theories will allow an understanding to be obtained of how consumers perceive CRM and the rationales of their engagement.

2.2.1 Attribution Theory

Attribution theory is normally used as a vehicle to identify how consumers actually look at companies’ CRM campaigns. Attribution is where people connect underlying causes or explanations to specific events (Kelly, 1973). Perhaps similar to this, individuals try to think of why certain actions have happened and make assumptions regarding the causality behind events (Dean, 2003). Relating specifically to CRM, Ellen et al. (2000) explained that consumers respond to CRM campaigns by making assumptions about a firm’s underlying motives behind the prosocial behaviour before they look at the marketing campaign. This has the implication that consumers use aspects of a CRM offer to make assumptions about a company’s motive. If consumers perceive a CRM offer as self-interested behaviour, they may view CRM as just being an adjunct to achieving the financial objectives of the company, such as sales and profits, and will thus view this brand unfavourably. However, if consumers observe some altruistic or other commendable motives to the CRM offer, they might respond to it in a better manner (Smith and Alcorn, 1991; Webb, 1999, as cited in Cui et al., 2003). Therefore if consumers develop attributions regards corporate motives for improving society from CRM campaign, these attributions should exert some positive influence on later attitudes and behaviour (Dean, 2003). However, the attribution process is subjective, depending on consumers’ own characteristics that influence who they respond to a CRM campaign (Cui et al., 2003) which means different consumers may have different attribution process that would interpret CRM in a whole host of manners. Therefore, in order to achieve effective and successful CRM, recognising the characteristics of consumers are significant underlying antecedents.

2.2.2 Exchange theory

In social science context, exchange theory explains human interactions as being a process where each party (or person) exchanges commodities, skills or resources in an attempt to optimise the amount of resources at their disposal (Ross et al., 1991). For the transaction to be successful, it must be beneficial to all parties (Howard & Crompton, 2004). When the theory is applied to marketing, Bagozzi (1975) elucidates that marketing exchanges can be categorised into utilitarian, symbolic or mixed. In a CRM campaign, the exchange is not monetary, rather it is a symbolic exchange, which has value and authenticity (Ross et al., 1991). Cause-related marketing is a strategic positioning method and marketing tool that publicly associates a for-profit organisation with a non-profit company and a relevant social cause, thus possibly appealing to the consumer’s emotions (Southall and Nagel, 2007). This can raise money for the non-profit entity and probably benefit the company conducting CRM campaigns (Polonsky and Macdonald, 2000; Pringle and Thompson, 2001).

2.3 Antecedents of CRM

CRM was realised as being powerful, with the antecedents of it being valuable to be identified. Tsai (2009) conjectures that the motivational attribution process, which determines perceptions of certain corporate motives for CRM engagement, is the central determinants for the success or failure of CRM activities. The occurrence of positive attribution induces consumers’ personal moral judgement or characteristics (Hammad, 2014), which would be basic antecedents of a successful CRM campaign. There have been many studies conducted which have attempted to determine the eminent attributes of consumers who are likely to respond positively to corporate social activities (Bennett, 2009; Bloom et al., 2006). The personal morals of the individual generally form the consumer’s own world view and perceptions toward different kinds of activities (Ladero et al., 2014).

2.3.1 Altruism

The engagement of individuals in such prosocial activities stems from an association between altruism and happiness (Hammad et al., 2014). Benefits of such an altruistic purchase include the welfare of society or others from the pro-social behaviour such as donation (Koschate-Fischer et al., 2012). Green and Peloza (2011) note that that consumers recognise a company’s social or cause related activities as an altruistic behaviour, if it is not tarnished by the perhaps underlying theme of obtaining more financial remuneration. A significant amount of the literature has suggested that CRM possess socio-psychological underpinning altruism (Moosmayer and Fuljahn, 2010). The altruistic values of consumers is an important antecedents for operating CRM campaigns, empathy is usually stated as something which can drive people to behave more altruistically and prosocially (Moosmayer and Fuljahn, 2010). One may get a positive feeling from donating to others (Hammad et al., 2014; Strahilevitz, 1999). The stipulations of altruism is such that it people who commit such altruistic acts are defined as being ‘altruistically motivated helping is directed toward the end-state goal of increasing the other’s welfare’ (Batson et al., 1983: 291). Simply, people who are more altruistic tend to believe that corporate motives are more altruistic and are more likely to react positively toward companies’ such activities (Ferle et al., 2013).

2.3.2 Egoism

It has been widely stated that, as the antithesis of altruism, egoism refers to the benefits derived from making themselves better (Koschate-Fischer et al., 2012). This is related to an individual’s ego-enhancement motivation such as self-esteem or self-confidence which can have an effect about caring for other’s well-being (Capara and Steca, 2005). Ego enhancement motivation usually allows individuals to help others in order to protect and enhance their personal egos (Basil and Weber, 2006). A research based on volunteerism has stated that, apart from being motivated by altruism, people are also likely to perform pro-social behaviour for the reasons of their personal growth and self-development (Clay et al., 1998). Evidently, pro-social behaviours such as donating or volunteering can allow individuals to prevent or enhance their self-esteems or egos (Basil and Weber, 2006). Therefore, self-confident individuals tend to believe their capacities which can effectively help others in need and are more likely to positively and actively react to the social events that influence social issues (Youn and Kim, 2008). However, a study conducted by Green and Peloza (2011) shed more light on this matter where respondents answered that functional value of products such as quality is something of greater importance to them and were not likely to integrate self-confidence in their decision-making.

2.3.3 Social resources

It has been stated that social capital can crucially affect the contributions that people make to the social welfare or helping (Bekker et al., 2005). This is often obtained from information, contacts and encouragement, which are gleaned from social networks (Lin, 2001). The greater the ranges of social networks people have the more stock of opportunities and information could be harnessed. However, human capital is a more affective factor than social capital for one’s prosocial activities. For example, people who are highly educated or have more skills and knowledge may bring more to their volunteering or social activities (Bekkers et al., 2007). This elevated status can also be attributed to higher and more sophisticated social networks among the higher educated (Brown 2002). If people are higher educated, they have access to similar people (Lin, 2001). In essence, it seems that it is essentially social resources which crucially mediate the effect human capital has in prosocial behaviour. It has been clearly stated that social resources such as relationship with friends or volunteering experience play a vital role in providing more opportunities to participate such social activities (Wilson, 2000). Extroverts may have the personality, inclination and connections to contribute more to pro-social and volunteering projects (Youn and Kim, 2008).

2.3.4 Skepticism

Skepticism is widely recognised as an individual’s doubtful and suspicious propensities toward an action (Gupta and Pirsch, 2006). The Oxford Dictionary (1982) formally defines a sceptic as a person who is inclined to enquire about the truth of facts, inferences, and so forth. Kanter and Mirvis (1989: 301), add that ‘sceptics doubt the substance of communications; cynics not only doubt what is said but the motives for saying it’. In the marketplace, skepticism generally emerges when consumers question the company’s motives for participating in its activities (Singh et al., 2009). That is, when consumers see a firm’s motive is self-serving or when they perceive that the firm is being deceptive and duplictious about its true motives (Foreh and Grier, 2003). When the consumers’ skepticism is applied to advertising, consumers tend to distrust and doubt advertising motives and claims (Thakor and Goneau-Lessard, 2009, as cited in Hammad, 2014). Advertising skepticism, a tendency toward disbelief of advertisements, could be influenced by corporate brand image or its corporate social responsibility (Boush et al., 1994). Consequently, this kind of propensity may lead low participation and ignorance against pro-social and charitable activities (Hammad et al., 2014). Consumer knowledge of advertisers’ motives and strategies impacts on how they interpret and respond to persuasive messages (Friestad and Wright, 1994). If a person adopts a critical stance towards advertising, they would interpret the contained messages from commercial advertising in a very negative manner. It seems true that as a component of persuasion knowledge, advertising skepticism refers to consumers’ negative attitude toward the motives of advertisers (Mangleburg and Bristol, 1998).

2.4 Outcomes of CRM

CSR is a particularly important asset and component of CRM and it has been strongly studied by companies, mostly likely due to its positive influence on consumer behaviour (Sen and Bhattacharya, 2001). CRM increases revenue and enhances perception through the firm’s support of charitable and worthwhile causes (Barone et al., 2000). The impact of CRM has been set against variables like consumer attitudes, consumer purchase intention, consumer perception and brand loyalty, with the final two attributes deemed to be the most important (Qamar, 2013; Quester and Lim, 2003).

2.4.1 Consumer Attitude

Consumer attitude is composed of three main attributes, namely consumer belief, feeling and behavioural intentions (Perner, 2010). Consumer attitude is key to a business marketing context, with many companies resorting to using CRM to try and change consumer attitude for the better (Ibid). The elaboration likelihood model stipulates that individuals will peruse over campaigns (and the messages encapsulated within them) for a lengthy period of time before changing their attitudes (Clow and Baak, 2005). When people recognise the message as being commensurate and aligning with their ideals and thoughts, high elaboration is formed and more positive attitude is shaped than when they consider as unimportant (Petty and Wegener, 1990). Marketing strategies exploit the growing conscience of people in society. For example, corporations have been promoting their activities of altruism and philanthropy in order to accentuate their positive corporate image and make a good impression in the mind of the consumers on the company (Qamar, 2013). Furthermore, Fuljahn and Moosmayer (2010) hypothesised that consumer attitude is influenced by a company’s pro-social activities.

2.4.2 Consumer Perception

Hanna and Wozniak (2013: 75) explain perception as ‘the process of selecting, organising, and interpreting sensations into a meaningful whole’. Historically, perception was affected by sense (hearing, sight, smell and taste), but this concept is redundant in modern society. Perception is highly subjective in that not only different people perceive same stimulus differently but even same person perceive given situations differently at difference circumstances and time (Hanna and Wozniak, 2013). Consumer perception is based on perceived value that the consumers’ overall assessment of utilities of certain products or brand (Zeithaml, 1988). Consumer perception theory verbalises that consumer perception contributes how individuals form opinions about corporations and the products they offer through the purchases they make. The consumer, as the largest group of stakeholders, considers ‘‘claim, ownership, rights, or interests in a corporation and its activities, past, present, or future’’ (Clarkson, 1995: 106). Companies try and get consumers to have a positive perception of them through the implementation of diverse marketing strategies. Consumer perception also refers to the reputation of the company, which can be enhanced by linking the brand or corporate name with socially worthy causes, enabling a company to strengthen its brand identity in the perceptual minds of consumers (Lavack and Kropp, 2003).

2.4.3 Brand awareness & Loyalty

Brand awareness

Brand awareness is an important concept in CRM. Keller (2003) defines brand awareness as consumers being able to differentiate one company from its competitors in the market. Consequently, many companies are trying to exploit the effects of brand awareness, particularly through the use of CRM (Shabbier et al., 2009). Looking at the significance of the associations people make with companies (Kaufmann, 2004), the majority of companies adopt CRM to increase brand awareness among their consumers to actively change their perceptions (Skory et al., 2004).

Brand Loyalty

The high levels of brand awareness generate greater consumer loyalty toward the brands (Keller, 2003). The increased brand loyalty helps the company to maintain strong market share and generate higher profit. For many brands, establishing brand loyalty and repurchasing behaviours is central to their success (Hallowell, 1996; Reynolds & Betty, 1999. Brand loyalty refers to the repeated purchasing behaviours of consumers over time (Bloemer and Kasper, 1995; Traylor, 1981). This means it has become more important for marketers to understand factors influencing brand loyalty to allow consumers to remain loyal to their brands. Fournier (1998) emanates that individuals, who are involved with many of brands, are likely to add some meanings to their lives some of which can be utilitarian or some are psychological and emotional. In modern society, it is clear that the perception of commendable corporate behaviour is increasingly affecting the overall evaluation of service by consumers which leads to brand loyalty (Salmones et al., 2005). If an association is made between the brand and other social values the customers’ values, this subsequently makes it possible for consumers to identify themselves with the brand and thus builds a stable and firm committed relationship with it (Adiwijaya and Fauzan, 2012).

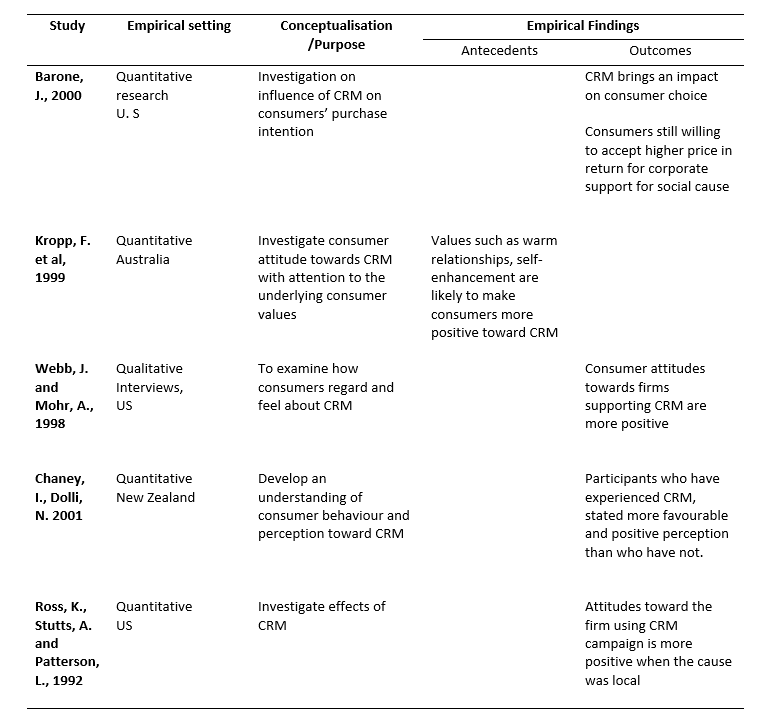

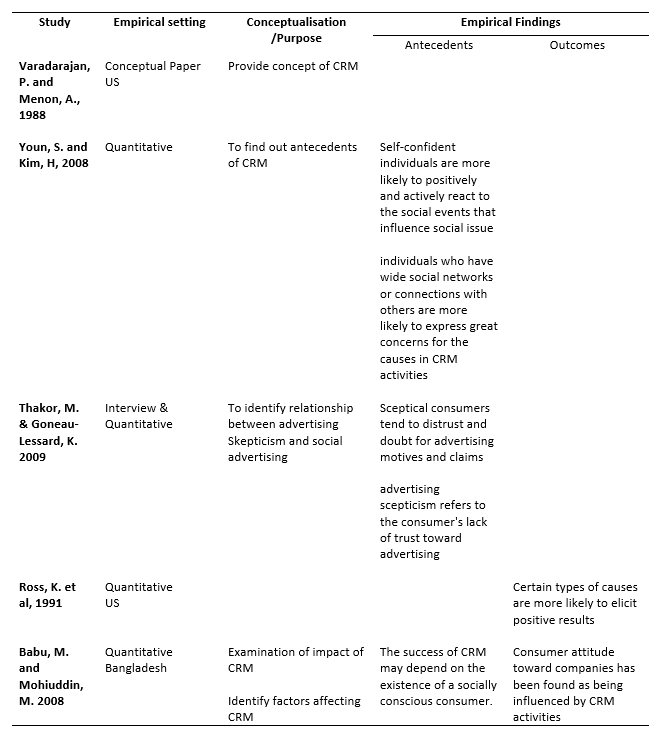

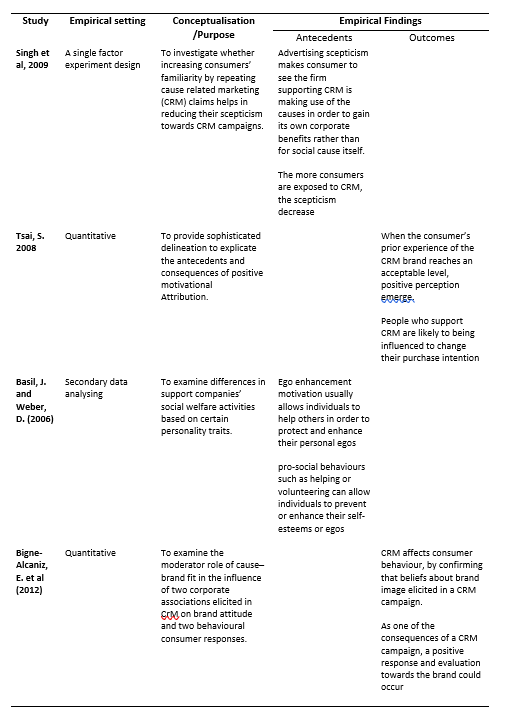

2.5 Empirical Findings

In the present business sphere, there have been a wide range of studies which have scrutinised the historical aspects of cause-related marketing. Many of studies have acknowledged that understanding relationships between drivers and CRM is crucial for their future segmentation of CRM activities (Barnes, 1992). However, it is still debateable whether CRM actually influences positive outcomes in practice. For example, according to a focus group survey by Boulstridge and Carrigan (2000), their respondents did not treat corporate’s philanthropic commitment as an important factor in their purchasing decisions but did value brand reputation or price as being more eminent factors. Despite this, the majority of the researchers discovered more than a scintilla of empirical evidences that supports the argument that a sustained commitment to ‘good’ causes by a company can affect customers’ choice and perception towards that firm (Barone et al., 2000).

2.5.1 Relationship between Drivers and CRM

Altruism and Egoism

Alluding to the work of previous studies, it is clear that altruistic behaviours such as caring about the welfare of others are motivated by a desire to help sustain one’s ego or persona, which contributes to the success of CRM campaigns (Basil and Weber, 2006; Clary et al, 1998; Crocker and Luthtanen, 1990; Staub, 1978). In contemporary society, the concept of ‘impure altruism’ which states that instead of being motivated solely for helping others or society welfare, people expect to receive other utility an exchange for giving, such as perks or other self-serving purposes (Koschate-Fischer et al., 2012). The individuals’ prosocial behaviour may be based on egoism (levels of self-confidence) and corporate cause supporting activities are used to maintain or enhance their self-confidence and prove to themselves that ‘they are doing good in society’ (Tesser, 1988). The brand marketer is advised to ensure that the consumer perceives the CRM promoted activities in more a egoistic way and contribute to a charity cause in order to gain self-satisfaction, which could be difficult to attain, if the advertising is concurrently trying to attract consumers by overtly highlighting their charitable behaviour and their altruistic motives in doing so (Mohr, 2006; Youn and Kiml, 2008; Tsai, 2009). Through the good that they procure, consumers may feel satisfaction with their self-confidence being maintained and this affirmation may drive them to repeat purchasing behaviour (Polonsky and Speed, 2001). According to Polonsky and Wood (2001), when consumers purchase such products, they may see themselves as ‘making a difference’ to society.

Social resources

The success of a CRM strategy may ultimately depend on how socially conscious a consumer is (Babu and Mohiuddin, 2008). People who are more extroverted may be more likely to participate in CRM campaigns and have greater social networks than introverts (Wilson, 2000). Networks increase the likelihood of connecting with other like-minded individuals (Becker and Dhingra, 2001). Brown and Ferris (2007) demonstrate that there is a positive correlation between a person’s social network and the extent of a person’s prosocial behaviour and that the magnitude of this relationship exceeds that of between volunteering and charitable giving to religious causes and between volunteering and charitable giving to secular causes. Essentially, the success of CRM relies on a consumer whose purchase behaviour will be influenced by an opportunity to help others (Webster, 1975).

Skepticism

It has been discovered that, as a part of general skepticism, advertising skepticism refers to the consumer’s lack of trust toward advertising (Thakor and Goneau-Lessard, 2009) and this sceptical attitude may reduce interest and recognition of the positive tenets of CRM. Singh et al. (2009) emphasise that those who are highly sceptical of advertising in general are likely to demonstrate a similar level of disbelief and scepticism towards CRM campaigns. This scepticism can be a real barrier to the success of CRM campaigns (Forehand and Grier, 2003).

2.5.2 Relationship between CRM and consumer Attitude

It is clear that a useful CRM strategy could result in shaping favourable consumer attitudes toward the firms. The majority of empirical researches have confirmed some positive effects of CRM on consumer attitudes (Kim and Kim, 2001). Bigne-Alcaniz et al. (2012) highlight the CRM effects on changing consumer attitude such as behaviour by ratifying that the opinions consumers hold over brand image displayed in a CRM campaign will influence the behaviour they display towards both the CRM campaign and the brand. In a survey conducted by Gard (2004), 60% of teens felt more favourably to and were more likely to buy brands that support charitable causes, perhaps reflecting the more acute morals possessed in society today (Gard, 2004). Nan and Heo (2007) also discovered that respondents who experienced CRM campaign or watched related messages were much more positively disposed toward an organisation compared to those who viewed a normal advert where CRM was not present. The differences of consumer attitudes toward CRM between buyers and non-buyers of CRM products were depicted in the research of Langen et al. (2013). Through the research, they found that while buyers agreed more strongly about the meaningfulness of CRM activities, non-buyers still held a relatively weak positive attitude regarding the companies’ pro-social activities. CRM was also proved to change consumers’ future attitude such as purchase behaviour. Irwin et al. (2003) uncovered that 45% to 65% of consumers respond that they will switch brands to those supporting social causes, although these findings should be taken with a degree of caution, given that it is only study. If consumers are convinced by the efforts of a CRM campaign, they are more likely to view it in a better light (Tsai, 2009).

2.5.3 Relationship between CRM and consumer perception

When CRM affiliates a company with a well-known and laudable cause, consumers can become more accepting of the brand (Berglind and Nakata, 2005), thinking that the company is motivated by philanthropic means, rather than for their own benefit (Barome et al., 2007). More and more companies are becoming engaged in cause-related charitable activities due to the positive outcomes CRM can have (Demetriou et al., 2009). Consumers eventually come to relate the brand with the charitable cause after intense CRM campaigns (Becker- Olsen et al., 2006, as cited in Bigne ́-Alcaniz et al., 2009). A quantitative research conducted by Chaney and Dolli (2001) saw that participants who have experienced or bought CRM products, possess more positive perception of the supporting company than the non-buyers, which seems a rational conclusion. A company needs to make it explicit that they are supporting a charitable cause to receive the full benefits of successful CRM campaign (Bloom et al., 2006; Tsai, 2008).

2.5.4 Relationship between CRM and brand loyalty

A significant amount of the prior research also revealed that cause-related marketing contributes generation of positive brand loyalty as increasing brand awareness (Polonsky and Speed, 2001), which make consumers motivated to buy a certain brands’ products continuously. Brink et al. (2006) looked at the extent to which CRM influences brand loyalty, with some studies revealing that consumers display more loyalty towards a brand if it supports a social cause rather than if it does not (Webb and Mohr, 1998). Research undertaken by Sen (2006) found that if consumers were more aware of the social causes a firm supported then they would be much more likely to show brand loyalty. Simply, if a brand has connotations of altruism, this means that a consumer will commit to a long term association with the brand (Adiwijaya and Fauzan, 2012).

3. Research Model and hypothesis

3.1 Introduction

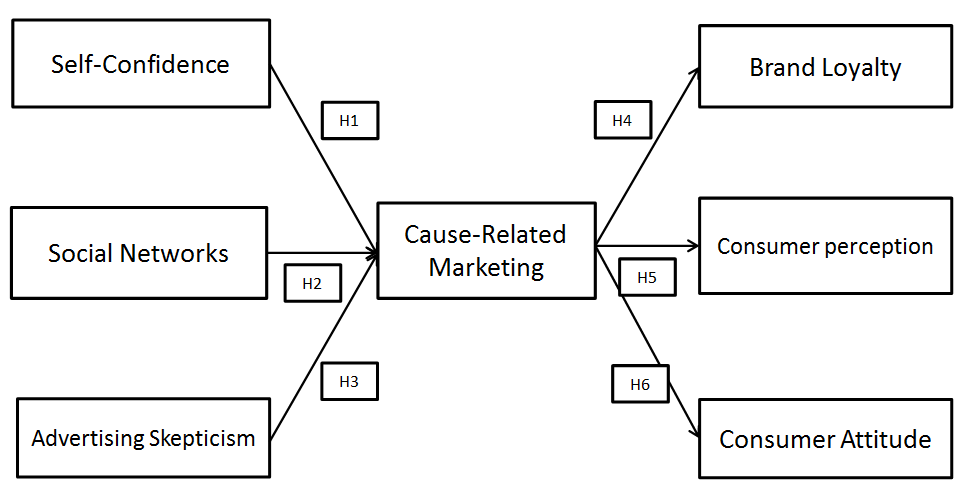

The research has been informed by the basis of a theoretical model which has been formed by a multitude of existing research and studies in this field (Erdogan et al., 2014 Thakor and Goneau-Lessard, 200 Babu and Mohiuddin, 2006; Fuljahn, 2010 Creyer and Ross, 1997, Erdogan et al., 2014, Quester and Lim, 2003; Brink et al, 2006, Salmones et al., 2005, Youn and Kim, 2008, Basil and Weber, 2006; Tsai, 2009, Hammad et al, 2014). A conceptual framework shows the three antecedents of CRM, with numerous hypotheses constructed to appraise the relationship between the variables (see next section).

3.2 Hypothesis development

Youn and Kim (2008) argue theorise that tied in with self-confidence; if people buy products which are linked to social causes then they feel this is a way of helping others. The CRM campaign relies on consumers whose choices of goods they wish to purchase will be influenced by an expectation of opportunity to help others (Webster, 1975). Under the guidelines of attribution theory, if consumers perceive the motives of CRM as corporate altruistic behaviour such as improving social welfare or helping people in need, they might buy the marketed products in order to enhance their self-confidence via the prosocial purchasing behaviour. In a similar manner to ego-enhancement, individuals engage in prosocial activities in order to create a desirable self-identity. Bigne’-Alcaniz, et al. (2009) theories that this modality of altruistic attribution is the most powerful antecedent to CRM campaign and can have a significant bearing on its success (Adiwijaya and Fauzan, 2012). Therefore, the following hypothesis is designed:

H1. People who have high level of self-confidence will positively support CRM campaigns

Kropp et al. (1999) theorises that people who have warm relationships with those in their lives are more inclined to volunteer or purchase socially ethical products. The social capitals from the relationship or membership which form a social network is regarded as one of the important influential motives for their supports toward cause-related activities (Penner, 2002). For example, the high levels of social networks may increase and provide possibility or opportunities to participate or access volunteering or social campaign. In regards to CRM, individuals who have considerable connections with others are likelier to be touched by the concerns listed in CRM activities as they may be more aware of the positive effects of the campaigns (Youn and Kim, 2008). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2. People with strong social networks will tend to positively support CRM campaigns

Individuals who are highly sceptical to advertising usually tend to show lack of connection with adverts and their purchase intention (Obermiller et al., 2005). They are likely to distrust marketing or any other advertising and this could make them believe that CRM is merely a strategy for a firm’s commercial interest and are less likely to respond positively (Bronn and Vrioni, 2001). Singh et al. (2009) supplement this argument with the point that skepticism of consumer is tied to the fact that they believe the company is only interested in themselves rather than genuine concern for the social cause itself. Exchange theory stipulates that a transaction may not occur if one side (or party) thinks there is nothing to gain. That is, people who are sceptical towards CRM would not feel anything to obtain through the purchase of CRM products. Therefore, those who are not sceptical about advertising would be more receptive to CRM. Hence, the hypothesis:

H3. Consumers with a low level of advertising skepticism will positively support CRM activities

Once consumers are familiar with a CRM brand to a certain level, this can instigate stronger moral satisfaction, which could leave them more likely to purchase the items in the future (Tsai, 2008). Consumers are more inclined to purchase goods from companies who are associated with causes (Nan and Heo 2007; Ross et al., 1992; Webb and Mohr, 1998). In this context, CRM could be used to elicit desirable attitude from consumers. Therefore, it is supposed:

H4. CRM will generate a positive change in consumers’ attitude towards promoted brands

As a major consequence of a CRM campaign, a positive response and evaluation towards the brand could occur (Bigne-Alcaniz, 2012). The impact of CRM initiatives could be that consumers’ positive perception of brand-social cause association would be accentuated. For example, if consumers hold a positive perception of certain brands, this may allow them to differentiate corporate image and be used as a shield against public criticism (Dean, 2003). When viewing a CRM campaign, consumers observe altruism from CRM-supporting companies and subsequently a positive perception of the brand emerges (Tsai, 2008). CRM can evidently improve brand image (Andreasen and Drumwright 2000; Carringer 1994, as cited in Polonsky, 2001) and this positive perception could culminate in brand loyalty. Therefore it is hypothesised that:

H5. CRM will positively affect consumer perception about certain brands

CRM, as a marketing purpose, provides several benefits to launched brands, with one of them being enhancing consumers’ loyalty and retention (Sheikh and Beise-Zee, 2011). CRM can certainly help cultivate better attitudes towards the organisation who (Nowak and Washburn, 2000; Lichtenstein et al., 2004, Hill and Becker-Olsen, 2006). People who support social cause would patronage specific brands and may not be easily swayed by the efforts of other brands. Brand loyalty allows companies to increase or charge premium prices and loyal customers are still willing to pay, as they see it as being a worthwhile cause that their profits are going to (Brink et al., 2003). The outcomes of a research project undertaken by Langen et al. (2013) were that 1 in 2 of the CRM consumers deviated from their normal brand to one which was promoted by CRM and actually stayed with it in the long term.

This gives substance to the formulation of the following hypothesis:

H6. Cause-Related Marketing will positively influence the promoted companies’ brand loyalty

4. Methodology

4.1 Introduction

Churchill (1995) reveals that the research design indicates the overall framework of a study, and the various processes entailed within it. Selecting a research design is regarded as a significant methodological decision, particularly in empirical research (Kinnear and Taylor, 2001). This chapter will critically appraise the selection of research design and the rationale for choosing this and how the sample was selected.

4.2 Research Design

In this research, as the data collection method, quantitative observation has been adopted in a structured manner in order to source quantitative data to produce numerical insights of antecedents and outcomes (Wilson, 2006). In order to explore pre-selected drivers influencing successful CRM, and impacts of CRM on consumer attitudes, perception and brand loyalty, a large sample size was required so that proper statistical analysis could be conducted. A qualitative approach is widely adopted when there is a problem in operationalisaion of concepts and hence it is difficult to use numerical methods of data collection (Barnes, 1996). Qualitative data collection method is used due to its potential to explore all potentially possible issues or variables regarding the phenomenon rather than test pre-identified hypothesis or questions in the forms of interview or observation (Harper, 1994). Therefore, quantitative research method was deemed appropriate for studying the large number of respondents and testing hypothesis using numerical analysis based on surveys (Harris, 2011) was selected.

Mainly, the research design could be separated into two broad concepts which are exploratory and conclusive design. Exploratory design is usually adopted with the primary objective to provide a more in-depth picture of the nature of marketing phenomenon (Malhotra and Birks, 2006). With a relatively malleable process, the research determines specifics, rather than general conclusions. As such, the forms of qualitative and quantitative exploration, unstructured observation, secondary data and qualitative interviews are used as methods of the research (Ibid). Contrary to this, conclusive research is designed to describe certain phenomenon, identify specific relationships and test hypotheses. Compared to exploratory research, typical conclusive research is more structured and based on a large representative sample. For that reason, researchers who planning qualitative research such as interviews are likely to adopt exploratory design while quantitative research is more fitting for survey based research. This is because exploratory research is appropriate when someone wants to obtain information where prior research has been conducted into the phenomenon. This research, which aims to identify hypotheses and which has been designed based on previous literature, therefore decided to opt for conclusive research.

Conclusive design can be sorted into causal and descriptive research. The major objective of causal research is to discover the evidence about cause-and-effect relationship mainly through an experimental method (Malhotra and Birks, 2006). Marketers try to see the causal relationship between factors and prove this through causal research. In the causal research, to find out causality, the environment is highly controlled and then researchers manipulate independent variables (cause) and check variance in dependant variables (effect), which could lead it open to accusations of bias. On the other hand, as a type of conclusive research, descriptive research aims to describe some characteristics or phenomenon (Malhotra and Birks, 2006). Unlike exploratory research, the research is based on prior formulation of specific research hypotheses and questions. Through the testing hypothesis, descriptive type of research helps to provide data that allows readers to identify and examine the connection between two items (Aaker et al., 2000). In this study, due to time constraints and restrictions on venues available for appropriate causal research experiments, a descriptive research design was instituted. Furthermore, compared to other types of research, a descriptive study is inflexible, structured, and normally encompasses a large sample size (Churchill and Iacobucci 2004; Hair et al., 2003). This research was planned using results collected from a survey method of research which necessitates a large sample size and aimed to determine relationships between each 6 variables (self-confidence, social-network, skepticism, attitude, perception and brand loyalty) with CRM. Further justification is given for using this research method as numerous researchers have noted that descriptive research designs are more effective for quantitative research in nature (Burns and Bush 2002; Churchill and Iacobucci 2004; Hair et al. 2003). Consequently, considering the characteristics of this study, descriptive research design was found to the best fitting for this study.

Cross-sectional studies, a common data collection method in descriptive research, collects information from a given sample group of the population at only one point in time while the longitudinal method is based on over a longer period of time with consistent participants (Burns and Bush 2002; Malhotra 1999). Longitudinal data enables marketing researchers to identify trends and monitor variables more closely. This could be useful in detecting changes due to some variables, however due to the inevitable time constraints, cross-sectional techniques has been adopted for this research instead. The cross-sectional study should minimise bias as it is a survey where participants are required to respond to a set of standardised and structured questions about what they think, feel and do (Hair et al. 2003), which should result in an accurate response.

4.3 Operationalisation of Constructs

Quantitative research was adopted because it is better suited to research tasks that involve the concrete operationalisation of constructs and statistical analysis of causal relationships (Denzin and Lincoln, 1994). Operationalisation concerns the manner in which a specific construct is to be measured. Measurement normally involves allocating numbers to set of items using a given scale or set of rules (Mlhotra, 2006). Constructs are the building blocks of academic research. Frazier (1999) notes that constructs represent abstractions that are intended to help researchers understand their field better. Measurement in research refers to the process of connecting the abstract concepts in the mind of the investigator with empirical indicators (Bagozzi, 1984). In essence, this part will provide an accurate assessment of the validity and success of the study.

4.3.1 Cause-Related Marketing

Importers were asked to clarify what extent that they agree or disagree with the statements with reference to pre-designed questionnaires from existing studies. Again the respondents followed the Likert seven point scale, ranging from (1) ‘Strongly disagree’ to (5) ‘Strongly agree’.

Table 1: CRM

| Items | Source |

| It really bothers me to find out that a firm that I buy from has act unethically | Creyer and Ross (1997), Erdogan et al., (2014) |

| I really care whether the brands I patronize have a reputation for CRM | Creyer and Ross (1997), Erdogan et al., (2014) |

| Whether a firm is ethical is not important to me in making my decision what to buy | Creyer and Ross (1997), Erdogan et al., (2014) |

| I really care whether the brands whose products I buy have a reputation for CRM | Creyer and Ross (1997) |

| It really please me to find out that a brand I buy from has acted CRM | Creyer and Ross (1997) |

| Companies’ efforts to support a social cause or solve a socialproblem with CRM campaigns are so beneficial | Erdogan et al. (2014) |

| CRM campaigns contribute to the improvement of society | Erdogan et al. (2014) |

4.3.2 Antecedents of Cause-Related Marketing

In order to ascertain the relationship between CRM and the three selected antecedents, participants were required to communicate the degree to which they agree or disagree with the statements collected from pre-designed questionnaires from existing studies. Again, the respondents followed the Likert seven point scale, ranging from (1) ‘Strongly disagree’ to (5) ‘Strongly agree’ to depict their answer.

Table 2 (Self-Confidence)

| Items | Source |

| I have more self-confidence than most of my friends by using CRM brands | Youn and Kim (2008) |

| I am the kind of person who knows what I want to accomplish in life | Youn and Kim (2008) |

| I feel satisfaction when I helping others | Hammad et al. (2014) |

| Participating in the CRM campaign induces pleasure and satisfaction in me | Hammad et al. (2014) |

| I feel like altruistic person when I purchase CRM brands’ products | Hammad et al. (2014) |

| Personally, assisting people in trouble is very important for me | Hammad et al. (2014) |

Table 3 (Social Networks)

| Items | Source |

| I would rather spend my time at social cause events rather than staying alone. | Youn and Kim (2008) |

| I have friends or neighbors who are already doing volunteering or other social events. | Becker and Dhingra (2001) |

| I wish I could spend more volunteering for good cause with my friends | Youn and Kim (2008) |

| I have worked in an organization for social cause | Becker and Dhingra (2001) |

| I enjoy participating in socially-friendly events | Youn and Kim (2008) |

Table 4 (Advertising Skepticism)

| Items | Source |

| Advertising for CRM brands insults my intelligence | Youn and Kim (2008) |

| I avoid buying products advertised on shows with too much social issue. | Youn and Kim (2008) |

| TV commercials place less emphasis on social causes | Youn and Kim (2008) |

| Advertising presents a false picture of the company being advertised as CRM brands. | Singh et al. (2009) |

| Most cause-related marketing do not provides consumers with essential information for social cause. | Singh et al. (2009) |

| Cause-related ads have unrealistic expectations about the type of desirable behaviors I should practice | Thakor and Goneau-Lessard (2009) |

| The messages conveyed in CRM advertising do not show reality as it really is. | Thakor and Goneau-Lessard (2009) |

4.3.3 Outcomes

The next part of the survey entailed respondents being asked to provide answers to what extent they agree or disagree with the below statements with regards to outcomes of CRM. Again, a Likert 5-point scale has been employed, anchored by (1) ‘Strongly Disagree to (5) ‘Strongly Agree’ to quantify whether the outcomes are affected by CRM or not.

Table 5 (Consumer Attitude)

| Items | Source |

| I would go several miles out of my way to buy from a brand that I knew to act CRM | Creyer and Ross (1997) |

| I would pay more money for a product from a CRM brand | Creyer and Ross (1997) |

| Given a choice between two firms, one with CRM and the other not especially so, I would always choose the CRM brand | Creyer and Ross (1997) |

| I will change a brand if it is not involved in any cause related activities | Babu and Mohiuddin (2008) |

| I will adopt a brand that does have any involvement with cause related marketing | Babu and Mohiuddin (2008) |

| In case of purchasing a new brand, I will choose the one which is involved in cause related marketing | Babu and Mohiuddin (2008) |

| If two brands are of the same price and quality, I will buy theone which supports a social cause. | Erdogan et al (2014) |

Table 6 (Consumer Perception)

| Items | Source |

| Firms who launch CRM activities should do well in the marketplace | Creyer and Ross (1997) |

| I believe to obtain more satisfaction from a brand that supports a social cause | Hammad et al. (2014) |

| My perception towards a brand changes if it is found to be involved in CRM | Fuljahn and Moosmayer (2010) |

| A brand affiliated with a cause can always carry the best benefits | Hammad et al. (2014) |

| After supporting CRM brands, I am now more willing to repurchase from those brands | Fuljahn and Moosmayer (2010) |

| CRM brands are a good way to raise money for a cause | Fuljahn and Moosmayer (2010) |

Table 7 (Brand Loyalty)

| Items | Source |

| I always think CRM brands over other brands when I consider buying something | Quester and Lim (2003) |

| I would pay more attention to CRM brand over other brands | Quester and Lim (2003) |

| I feel much attached to the particular CRM brands over other brands | Quester and Lim (2003) |

| Even though another brand is on sale, I would buy CRM brands | Quester and Lim (2003) |

| I would always find myself consistently buying CRM brands over other brands. | Quester and Lim (2003) |

| I shall continue with my operating CRM brand in the next few years | Salmones, M. et al. (2005) |

| I would recommend CRM brand if somebody asked my advice | Salmones, M. et al. (2005) |

4.4 Questionnaire design process

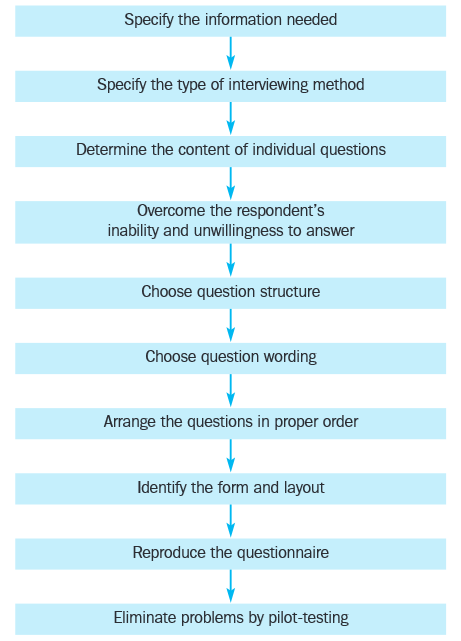

In this method of gaining information from a survey, for obtaining quantitative primary data, a standardised data collection process is required for accuracy and ease of analysis. A questionnaire can be defined as ‘A structured technique for data collection consisting of a series of questions, written or verbal, that respondents answer’ (Malhotra and Birks, 2006: 326). A standardised questionnaire ensures comparability of the data and increases the accuracy of the research (Ibid). Here, a ten step process has been initiated:

Questionnaire Design Process

(Mallhotra and Birks, 2008)

At the first step, the information needed should be specified. This is crucial as without clearly specifying what information is needed; there would be ambiguity in research questions. This study, which aimed to find out drivers and outcomes of cause-related marketing, needed information about how respondents think about three antecedents, CRM and three outcomes. After this, the data collection methods are considered. Questionnaires could be designed differently, depending on the types of method, for instance personal interviews and surveys need different questionnaires. This study based on online survey collected data as a type of self-administered survey. As the quantitative research was targeting many respondents (more than 100), the internet based method was superior to traditional survey methods.

Once the needed information is specified and type of method is decided, the next step is to determine the content of individual questions. Each question in a questionnaire should be related and contribute to information needed unless that question should be eliminated (Malhotra and Birsk, 2006). As mentioned in the ‘Operationalisation of Constructs’ stage, all questions in this research were abstracted from existing literature for reliability and validity. The next stage entails the researchers attempting to overcome the respondents’ inability and reticence to answer. For example, respondents are not fully informed about the topics of survey. Therefore, this survey provided brief description of the concept of CRM with examples for helping the understanding. In addition, as surveys were anonymous, this should have helped to reduce barriers, increase consent and allow participants to give a more honest response (Naser, 2014).

The 5th step is choosing a question structure in that a question could be structured or unstructured. This survey has been conducted with structured questions which give the participants answer using a set of already defined responses (Wilson, 2006). Apart from questions regarding demographic information, respondents were asked to rate the items using a five point Likert scale (ranging from 1= Strongly Disagree to 5=strongly agree) that requires the respondents to choose degree of agreement or disagreement with each of the statements (Malhotra and Birks, 2007). After this, the wording of the question should be made clear so that the respondents understand it with limited ambiguity. In order to limit bias and increase accuracy, questions had been carefully designed with clear wording. Questions are free from technical jargon and avoid ambiguous language such as ‘usually’ and ‘normally’. After the wording of the questions has been decided, the arrangement of the questions is subsequently considered. Items for CRM are firstly asked and three antecedents and three outcomes are arranged subsequently. The forms, spacing and positioning of questions have a significant effect on the results, particularly in this kind of online self-administered survey, so care must be taken not to influence the participants’ responses (Malhotra and Birks, 2006).

After arrangement of the questions, the form and layout was identified. Questions in each part were numbered and questionnaires were divided into several parts. In the penultimate stage, questionnaires were reproduced to make them accessible to read and easy to answer. The final step constitutes a pilot (or preliminary) test, which tests the questionnaires on a small-size sample of participants to amend the study if potential problems are selected. In order to see whether the questions are easy for participants to understand, the questions include any ambiguous questions to indicate if these are superfluous to the research project (Brace, 2004). From the test, it was discovered that one or two questions were confusing, meaning they were subsequently amended. For example, the leading question ‘TV commercials place too much emphasis on sex’ was modified, with ordinary and topic-relevant statement, to ‘TV commercials place less emphasis on social causes’.

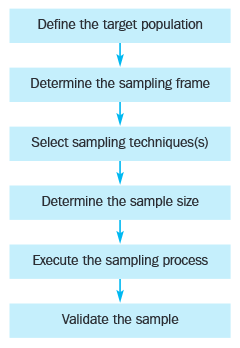

4.5 Sampling design process

A sample is took of the total population being sampled due to the time constraints which constrict the study and practicality reasons. In order to draw an appropriate sample for this research, the widely-renowned six-step of sampling process has been adopted (Malhotra and Birks, 2006).

The Sampling Process Design

Source: Malhotra and Birks, 2008

Initially, the target population was carefully considered and specified. In this study which was designed to find out what drives successful CRM and its outcomes, actual consumers who have CRM experience who are older than 18 were included in the target population. Once the target population is defined, the next step is to determine sampling frame which is a representation of the target population (Ibid), which could be drawn from a list or database. Unfortunately, there has not a proper sampling frame to access for the database of cause-related marketing. Therefore, a pre-email was distributed to see whether participants had purchased CRM products or not.

The third step involves selecting what sampling technique will be used. This research applied the traditional sampling approach with the entire of the sample being selected before the data collection. Furthermore, sampling without replacement was used that once selected sample was removed from the frame. As the final and the most important decision about sample technique, probability sampling technique was operated. Compared to non-probability sampling which relies on judgement of the researchers, probability sampling depends on change (Malhotra and Birks, 2006). This is that the sample was selected randomly without any pre-judgement. Sample size refers to the number of participants to be included in the survey and is the next step of this model. As the appropriate sample size for the marketing studies, Malhotra and Birks (2006) suggest 200 participants in their scholars. This meant that 200 respondents were determined as the size of the survey and targeted. After this, the sampling process was executed that through the social media message and email has been sent to randomly selected sample. Finally, sample validation was performed as the ultimate stage of sample design process.

4.6 Conclusion

Corporations employing CRM campaign or planning can consult the results of this study, which provides good generalisation of the results (Westat, 2002). This method is precise and convenient in that statistical software (SPSS) is used instead of the researcher analysing the data manually (Johnson and Christensen, 2010. In the next chapter, the statistical results and findings will be analysed by SPSS and interpreted to prove the hypothesis.

5. Analysis & Results

5.1 Introduction

The principal objective of this research is to investigate whether the antecedents (self-confidence, social networks and advertising skepticism positively affect cause-related marketing and influence of CRM on expected outcomes (consumer attitude, perception and brand loyalty). The collected data was analysed through a series of mathematical tests: Pearson correlation, bivariate regression and multiple regression analysis all being applied. As both the independent and dependant variable of all the hypotheses are continuous, ANOVA or t-test which is appropriately for categorical variables is redundant in this case and was not applied. Even though categorising the independent variables into a high and low group was possible, this could distort the pattern of the data and result in inaccurate results. A correlation has been conducted for proving relationship between independent and dependant variables and bivariate and multiple regression methods were used for proving hypothesis. To prove hypotheses 1, 2 and 3, that there are three independent variables (self-confidence, social networks and advertising skepticism) and one dependant variable (CRM), multiple regression has been conducted. In contrast, bivariate simple regression has been used for validating (or not) hypotheses 4, 5 and 6 which have one independent and dependant variable respectively.

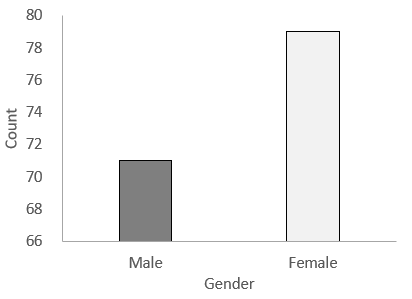

5.2. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Sample

The bar charts below show that in total, 150 people participated in this survey and male respondents accounted for 47.3 per cent (71) and 52.7 per cent were female (79). The actual number of participants was 164, although 14 questionnaires were not completed and thus were removed from the data collection.

Chart 1 (Gender)

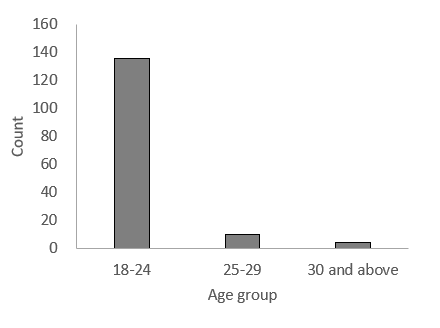

Chart 2 (Age group)

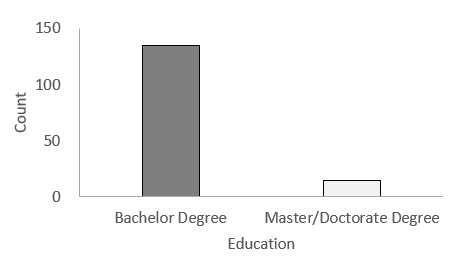

Chart 3 (Education)

The vast majority of participants (136) are aged between 18-24, with only 10 and 4 people being from 25-29 and 30 and above groups respectively. In terms of the educational attributes of the sample, 90 (135) per cents of participants have a Bachelor degree and only 15 people have a Masters or Doctorate degree, with the small proportion of the sample having studied past Undergraduate (Bachelor) level being seemingly representative of the population.

5.3 Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics are normally used as a method of displaying and summarising the collected data. This part of the data analysis is particularly useful for an individual who wants to make some general description regarding the data collected through the survey before starting analysis (Coakes et al., 2007). Descriptive statistics mainly provide values such as mean and median (measures of central tendency) and standard deviation (measure of spread). Appendix 2 illustrates the percentages of responses on each scale of each question of variables.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | Range

|

Mean | Std.Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||

| Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Std. Error | Statistic | Std. Error | |

| Cause-Related Marketing | 1-5 | 3.59 | .657 | -.541 | .198 | .664 | .394 |

| Self-Confidence | 2-5 | 3.72 | .610 | -.685 | .198 | .693 | .394 |

| Social Networks | 1-5 | 3.85 | .639 | -.847 | .198 | 1.528 | .394 |

| Advertising Skepticism | 1-5 | 2.87 | .696 | -.418 | .198 | -.261 | .394 |

| Consumer Attitude | 1-5 | 3.09 | .648 | -.303 | .198 | .366 | .394 |

| Consumer Perception | 1-5 | 3.63 | .691 | -.881 | .198 | 2.168 | .394 |

| Brand Loyalty | 1-5 | 2.86 | .803 | -.136 | .198 | -.273 | .394 |

The chart above illustrates the summary of each variable. For example, the minimum scale of CRM is one and the maximum is 5 with 3.59 mean values and .657 Std. Deviations. Deviation refers sto the spread of set of observation in that the greater the standard deviation is, the greater the dispersion of the observations. Descriptive statistics also provides information about the distribution of scores (normality) on continuous variables (skewness and kurtosis). The skewness value indicates the symmetry of the distribution whereas kurtosis provides information about the ‘peakedness’ of the distribution (Pallant, 2007). All skewness values are less than 2 (<2) and all kurtosis values are less than 4 (.4), which shows that there is no problem in normality.

5.4 Reliability check

Prior to commencing analysis, there is one other technique which must be used to ensure validity. As all the questions of each variable group are based on scales, it is important see whether the scale are reliable or not before using them (Pallant, 2007). Therefore, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient has been instituted as an indicator of the reliability of scales and also check their internal consistency. Internal consistency is importantly used to explore the extent to which all the items in the survey measure the same concept and hence it is directly connected to the inter-relatedness of the items in the test (Tavakol and Dennick, 2011). Therefore, if the value of Cronbach’s Alpha does not meet a certain level, some items should be removed or modified prior to beginning analyses. There are several different reliability coefficients, but one of the most prevalently used and reputable indicator is Cronbach’s alpha, hence providing the rationale for using it in this study.

Table (Cronbach’s Alpha)

| Group | Cronbach’s Alpha | Cronbach’s Alpha Based on Standardized Items | N of Items |

| Cause-Related Marketing | .823 | .824 | 7 |

| Self-Confidence | .764 | .773 | 6 |

| Social Networks | .765 | .772 | 5 |

| Advertising Skepticism | .830 | .827 | 7 |

| Attitude | .805 | .805 | 7 |

| Perception | .860 | .861 | 6 |

| Brand Loyalty | .918 | .919 | 7 |

It is clear from the results above that all the Cronbach’s alphas exceed 0.7. Ideally, Cronbach’s alpha should be higher than 0.7 and above (DeVillis, 2003, as cited in Pallant, 2007). Even though some groups such as Self-Confidence and Social Networks might be higher after modification and amendment based on standard items, they are still reliable enough to analyse (over .7). No question was deleted.

5.5 Correlation Analysis

For the purposes of assessing the direction and strength of a relationship between two variables (i.e. CRM and each variable), correlation analysis was instituted. Pearson’s correlation coefficients have been measured in this study and they are widely regarded as the most appropriate indicator assessing the association between variables that are measured using interval or ratio type scales. A positive (0<r<1) correlation indicates that when the value of one variable increases, that of the other variable also tends to increase and negative (-1<r<0) correlation means a relation that as one increase the other one tends to decrease (George and Mallery, 2000). If there is a Pearson’s value of 0, this means that there is no relationship between two variable and 1 indicates that there is a perfect positive correlation while the value of -1.0 means the inverse, a totally negative correlation (Pallant, 2007). The magnitude of this Pearson’s figure is illustrated by Cohen (1988) who suggests the guidelines of interpretation which is small (r=.10 to .29), medium (r= .30 to .49) and large (.50 to 1.0). Significance (p), indicates ‘how much confidence we should have in the results obtained’ (Pallant, 2005: 133). As all the variables in this research are continuous variables, a parametric Pearson correlation analysis was instituted. Additionally, due to the theoretical frameworks used in the study (Youn and Kim, 2008; Singh et al., 2009; Tsai, 2009), the direction of relationship has been known in advance (antecedents (i.e. self-confidence, social networks, advertising scepticism) to CRM and CRM to outcomes (attitude, perception and brand loyalty), which meant that the 1-tailed significance was selected.

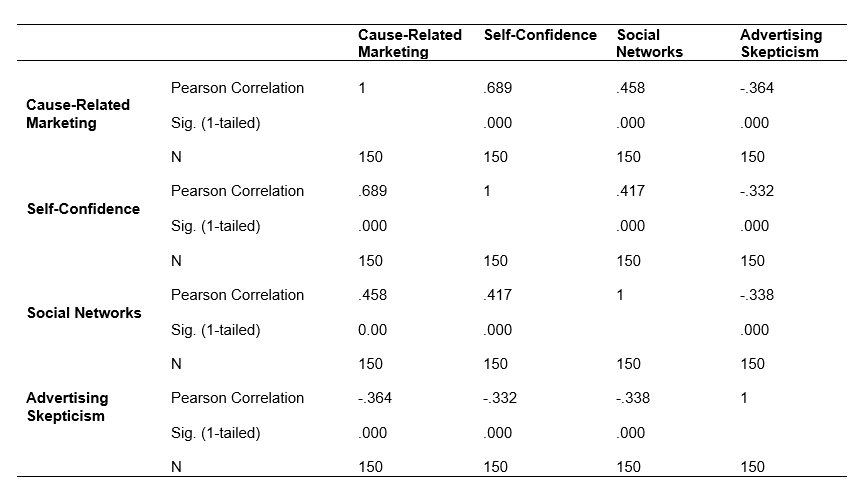

Table (Correlation-1: Antecedents and CRM)

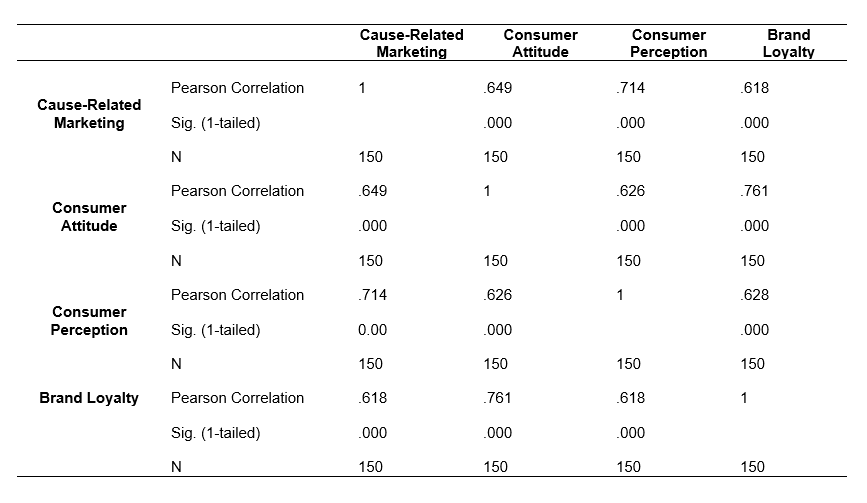

Table (Correlation-2: CRM and Outcomes)

From the table of CRM and antecedents variables, the Pearson Correlation (r) between CRM and self-confidence and social networks are positive (.689 and .458). This means that there is a strong correlation between CRM and self-confidence and medium correlation with social networks. In contrast, there is a medium-sized negative (-.364) correlation between CRM and advertising scepticism which infers that as one of the variables increase, the other one tends to increase and vice versa. Looking at the results of the CRM and outcomes table, Pearson Correlation (r-value) for CRM and all variables are above .5 (.649, .714 and .618) and positive, so this means that it has the implication that there is a significant positive correlation between CRM and each outcome variable. From the results, it is found that there is the most significant relationship between CRM and Consumer Perception (.714) and the weakest correlation in CRM and advertising scepticism (-.364).

5.6 Hypothesis Tests

Regression analysis is considered a useful and powerful analytical method and is frequently employed to investigate all types of dependence associations (Field, 2013; Hair et al., 2013). For the purpose of this thesis, the current study also employed regression analysis in order to examine and analyse the relationships between both a single dependent variable and a single or several independent variables. There are two types of regression analysis that when the problem includes a single independent variable, simple regression analysis is applied, but when it includes two or more independent variables multiple regression analysis is employed (Field, 2013; Hair et al., 2013). Therefore, in this study, multiple regression was demonstrated in order to test the hypotheses 1, 2 and 3, while simple regression had the function of examining the association between CRM and each outcome (i.e. hypothesis 4, 5, and 6).

5.6.1 Antecedents of CRM

In order to prove hypothesis 1, 2, and 3, multiple regression analysis has been conducted. The analysis was used to investigate the effects of independent variables (self-confidence, social networks and advertising scepticism) upon a solitary dependant variable (cause-related marketing).

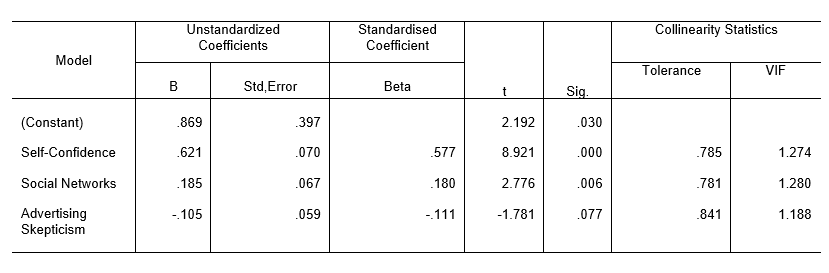

Table 6 (Coefficients: Multiple regressions)

SPSS provides ‘collinearity statistics’ part in the Coefficients table on the variables as part of the multiple regression procedure. This helps to identify the problem of multicollinearity that if the problem is found, the multiple regression will fail to run (Kinnear and Gray, 2008). Two values are given which are Tolerance and VIF. Tolerance is “an indicator of how much of the variability of the specified independent is not explained by the other independent variables in the model” (Pallant, 2005: 150). If this value is minute (less than .10), it indicates that the multiple correlation with other variables is high, suggesting the possibility of multicollinearity problem. The other value given is the VIF (Variance inflation factor), which is the inverse/reciprocal of the Tolerance value (1 divided by Tolerance). If the VIF values are above 10, this would be a concern here, indicating multicollinearity. However, as can be observed from the coefficients table, all Tolerance values are higher than .10 (.785, .781, and .841) and all VIF values also less than 10 (1.274, 1.280, and 1.188), meaning that this multi regression can be run.

Moving on from this to the beta part, self-confidence and social networks variables have positive Beta value (.577 and .180). This explains that both variables positively affect variation of dependant variable. Conversely to this, the Beta value of Advertising Skepticism is negative which means that negatively effects the dependant variable. The Beta in standardised coefficients chart identifies the independent variable which exerts the strongest influence on a dependent variable. Therefore, variation in Self-Confidence independent variable (0.577) causes the biggest variance in dependent variable (CRM) than others (.180, -.111). The p value (Sig.) is used as an indicator to prove or disprove hypotheses. When p is lower than 5% (i.e. p<.05), it is evident that the variable is significantly contributing to the equation for predicting ‘math achievement’ (Morgan et al., 2013: 168). Therefore Self-Confidence and Social Networks, which have acceptable p values (.000 and .006<.05) and have positive Beta values, positively affect CRM, which corroborates earlier evidence provided in this literature review. Even though the Beta value of Social Network is small (.180), the p-value is lower than .05, meaning that while the influence is not strong or statistically significant, social networks still positively influence CRM. This means that hypothesis 1 and 2 are supported. However, the p value of Advertising Skepticism, which is bigger than .05 (.077), indicates that there is no significant influence in the variable on CRM, which means that hypothesis 3 is rejected.

5.6.2 Outcomes of CRM

In order to test and examine the hypothesis 4, 5 and 6, which has been designed to find out whether the independent variable (Cause-related Marketing) has a positive influence upon each outcome variables, a simple bivariate regression has been conducted. According to the stipulations of the framework model, while the relationship between antecedents and CRM has three independent variables and one dependent variable, there is only one independent variable (CRM) and three different dependent variables in the relationship between CRM and outcomes. Therefore, unlike the hypothesis 1, 2 and 3, which used multiple regression analysis, a simple bivariate regression has been applied to test hypotheses 4, 5 and 6. Initially, the relationship between CRM and Consumer Attitude has been analysed.

Table (Model Summary (CRM-Consumer Attitude))

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Durbin-Watson |

| 1 | .649 | .421 | .417 | 1.716 |

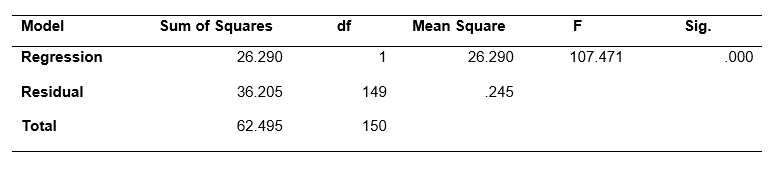

ANOVA- Table (Cause-related Marketing-Consumer Attitude)

From the model summary table, the R Squared value has been checked in order to find out what extent the independent variable makes a difference to customer satisfaction. This value indicates how much of the variance in the dependent variable is explained by the model. Therefore, it could be surmised that CRM accounts for 42% of the variations in Consumer Attitude. The next step demonstrates that the ANOVA table provides the test of the statistical significance of the regression (Morgan et al., 2013). Essentially, this table presents whether the regression model predicts the dependent variable significantly well or not. From the ANOVA tables, it was revealed by the Significance column which tells it is suitable for using regression (P=0.000 <.05). This illustrates that the independent variable is significantly intertwined and connected with the dependent variable. Hence, hypothesis 4 is accepted.

Table (Model Summary (CRM-Consumer Perception))

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Durbin-Watson |

| 1 | .714 | .509 | .506 | 1.839 |

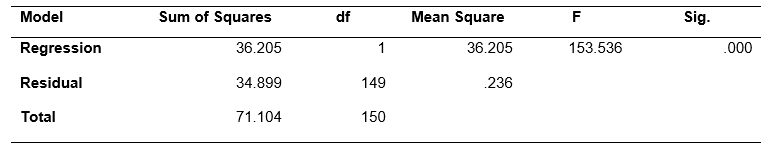

ANOVA- Table (Cause-related Marketing-Consumer Perception)

For the hypothesis 5, identical to before, simple regression was used to investigate how well CRM predicts consumer attitude. The model summary table (R Square value) indicates that 51% of variance in Consumer perception is explained by CRM. P value (<.05) in ANOVA table tells the regression can significantly be used to project the relationship between CRM and Consumer Perception. Therefore, hypothesis 5 (that CRM has positive influence upon consumer perception)n is accepted.

Table (Model Summary (CRM-Brand Loyalty))

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Durbin-Watson |

| 1 | .618 | .382 | .378 | 1.725 |

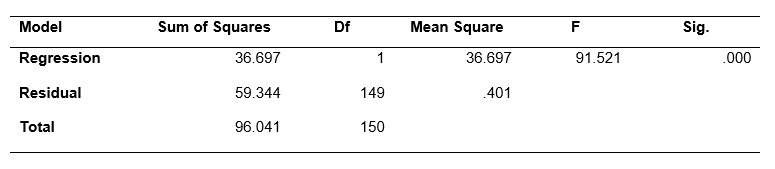

ANOVA- Table (Cause-related Marketing-Brand Loyalty)

Finally, CRM and Brand Loyalty has been analysed in order to test the validity of hypothesis 6. The results were statistically significant (p<.05) and suitable to use for regression analysis. The value of R value was 0.38 and this indicates that 38% of the variance in brand loyalty was explained by CRM. Cohen (1998) views this as having a large effect. The ANOVA table also shows it is acceptable to use simple regression (p<0.05). This means that hypothesis 6 has been proved.

5.7 Summary

From the analysis, all hypotheses, except 3, have been accepted. From the multiple regression analysis, self-confidence is revealed as the most influential antecedent for a successful CRM campaign. Adjacently, through the simple bivariate regression analysis, it is determined that CRM has the most significant impact on consumer perception (51%) and consumer attitude and brand loyalty respectively (42% and 38%).

The acceptance (or rejection) of the two hypotheses is summarised in the following table:

| Hypothesis | Accept/reject |

| H1. People who have high level of self-confidence will positively support CRM Campaigns | Accept |

| H2. People with strong social networks will tend to positively support CRM campaigns | Accept |

| H3. Consumers with a level of advertising skepticism will positively support CRM activities | Reject |

| H4. CRM will generate a positive change in consumers’ attitude towards promoted Brands | Accept |

| H5. CRM will positively affect consumer perception about certain brands | Accept |

| H6. Cause-Related Marketing will positively influence the promoted companies’ brand loyalty | Accept |

6. Conclusion and discussion