Introduction

According to Bass (2019), leadership is the process of leading an organisation or a group of people to attain certain laid or known objectives, whereas leadership principles are guiding beliefs, actions, or attitudes that leaders implement to attain the set goals. However, several scholars have had diverse perspectives on defining leaders. For instance, Samimi et al. (2022), affirmed that a person or organisation undertakes leadership to lead other crowds or firms. Notably, the implemented principles play a critical role in defining what kind of a leader is; fundamentally, poor, or sustainable. Diverse from management, leadership is about more than just seniority or ranking positions in hierarchies of organisations, who are path-followers, but innovative personnel ambitious to attain organisational goals (Samimi et al,. 2022). In reference to Samimi et al., (2022), strategies deployed by a leader significantly define what kind of leaders firms have. Leaders are not managers, although they have several common traits in the jurisdiction of their service. Management is all about controlling people or entities to attain a certain goal, while leadership is more about the ability to motivate, influence, and enable subordinates to contribute towards the realisation of set objectives (Samimi et al., 2022). Therefore, to inspire and influence make managers different from leaders, but not control and possession of power. Millions of leaders have failed to achieve their goals mainly because they need to differentiate themselves from managers (Samimi et al., 2022). For instance, M.K Gandhi was an Indian hero who inspired crowds of residents to fight for the country’s independence in 1947 (Balasubramanian et al., 2020). Gandhi’s vision was everyone’s dream and ensured his strategies were unstoppable. Therefore, the globe will always require leaders like him who think beyond problems, have a vision and are always ready to inspire. According to (Haque and Ahmed (2021), over the last two decades, the globe has been highly depicted with aggressive entities eager to dominate the market, particularly the automobile sector. Besides, the markets have been severely ruined by disasters, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, issues of Global Financial Crises (GFC), talent shortages, wars, oil crises and other issues of economic recession (Jain & Siddiqui, 2022. According to Jain and Siddiqui, 2022) courtesy of such unfortunate issues have made established corporations not withstand or bear, and instead collapse, whereas the states bailed down others. BMW’s ultimate status was highly dependent on the leaders’ quality before and during the reigns of economic crises (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). For instance, if the corporations had sustainable and competent leaders, prospered well during the severe reigns and did not go into insolvent cases. This essay is predominantly about Bayerische Motoren Werke (BMW) and how it manoeuvred during periods of economic recession courtesy of competent leaders.

The Organization (BMW)

The entity was founded in 1916 by Camillo Castiglioni, Karl Rapp, Gustav Otto, and Franz Popp and headquartered in Munich, Germany, to manufacture aircraft engines. Over the decades, the firm witnessed various commercial crossroads, making it not stick to a single business. For instance, the corporation manufactured aircraft engines from 1917 to 1918 and terminated the business from 1933 to 1945 during the recession that the World Wars triggered (Moellers et al., 2019). Nowadays, BMW has about 96,000 employees at its 24 production sites in 13 countries and, perhaps, conducts global sales in over 120 countries (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). Over the reigns, the company has diversified its production to manufacture cars and motorbikes to reach broader markets under three interdependent brands: MINI, BMW, and Rolls Royce (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). Auspiciously, in an industry highly depicted with mergers, acquisitions and consolidations, BMW has been and is an independent entity that makes considerable profits, despite being hit by varied tragedies; Global Financial Crises (GFC), Covid-19 pandemic, and oil crises. Amongst other thousands of automobile companies, BMW emerged strongly, recording massive profits in 2010 (Moellers et al., 2019). In reference to Avery and Bergsteiner (2011), most automobile car companies were shut down, and others took insolvency after the recession periods. For instance, entities such as General Motors (GM) and Fiat experienced difficulties mandating them to insolvency levels (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). Prior to the GFC, BMW had made significant profits and, during the recession, firmly survived and continued to pay dividends, although profits fell sharply. In regards to Avery and Bergsteiner (2011), in 2010 after the recession, BMW had a net worth of about $42 and was in a solid financial position. However, after the depression period, automobile entities started to recover strongly.<a

Survival Techniques

Avery and Bergsteiner (2011), clarified that the efficient survival of the entity in depression and immediate resilience were contributed by three factors: the creative initiatives deployed, its business model, and eventually, its sustainable leadership approach. However, these aspects are ignited and anchored to the entity’s long-term strategies that necessitate dynamic performance and easy flow of events when attaining suitability in everything engaged. Multiple strategies were deployed, but the previously affirmed ones played a pivotal role in transforming the entity.

Business Model

In its business model, BMW incorporates flexibility for clients, employees and the firm (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). Therefore, in the business model, all stakeholders are critically cared for by the entity. Primarily, BMW makes vessels on conditions. For instance, they pave the opportunity for manufacturing cars only if an order has been made by clients, especially during recession periods (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). Like other industries, the automobile is predominantly occupied with luxury goods, which clients only choose when they have settled their basic needs.

Moreover, since BMW was launched adhered to producing quality goods, which made it acquire a significant market share in the industry due to meeting diverse client preferences and eventually attaining a competitive advantage. Therefore, making cars only on an order basis will facilitate the entity to retain clients and evade and avoid material wastage, in case new brands pave that are more innovative. According to Avery and Bergsteiner (2011), the principle also allows the entity to scale on working periods and production of cars depending on the demand for the ordered cars. In its strategies, BMW has deployed mass customisation for the clients to specify what they need in the car in detail, a strategy that seduces thousands of consumers to their products (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). Courtesy of such reputation has made BMW upturn their sales even during severe reigns of economic recession. In reference to Avery and Bergsteiner (2011), the model allows about 300 work-time patterns that necessitate optimal utilisation of company employees’ skills and experience despite a huge unionised workforce. However, the company’s conventional three-shift model of the employee’s working strategies waves flexibilities in the working protocols as their offer workers extra hours during peak seasons and draw on them when tasks diminish (Wiprächtiger et al., 2019).

Creative Solutions

According to Krasheninnikova et al. (2019), increasing sales and attaining a significant market share is not a big deal, but retaining and maintaining sales is an awkward strategy. BMW deployed various creative initiatives to cater to the issue and maintain its competitive edge. For instance, to some extent, like the recession that occurred in 2008, which mandated the entity to reduce its working overheads, an incident severely altered its comparative and differential advantages (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). Therefore, to avoid massive losses and losing the entity’s reputation, BMW was eager to initiate close partnerships with unions and sought voluntary redundancies, encouraged workers to take early retirements, and not to have vacant positions that could make the entity incur additional costs. Alternatively, BMW terminated renewing contracts for temporary employees.

On the other hand, BMW was anxious and hesitant to lose its massive skilled and experienced employees, who would be instantly required when things turned right (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). Instead of terminating their contract and partially or wholly sacking them, BMW collaborated with the German federal government to shift entity employees to work four days a week instead of the entire week. In those regards, BMW could only pay wages for four days while the government could afford to pay them 80% of the fifth day instead of the total week’s unemployment wages (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). Apparently, this meant that the entity employees only lost 20% of their week’s wages and retained their jobs (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). This strategy reduced the company wages and retained skilled and experienced personnel.

According to Avery and Bergsteiner (2011), the other creative approach that necessitated BMW to prosper was the management of its suppliers, particularly during the recession periods. Over the time the entity was operating, suppliers played a vital role in affirming the entity about consumer preferences, an issue that has made the firm survive efficiently. In response, BMW has valued its suppliers and deployed significant efforts to maintain them. For instance, BMW conducted risk management to trace its suppliers’ perils of insolvency and gave loans, expert advice, and other benefits to keep them afloat, especially those ruined during the GFC (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). However, the creative solutions tackling BMW’s issues did not mean it was always the right strategy. In reference to Yadgarovna and Husenovich (2020), being creative does not mean always being right. Therefore, being creative comes along with various disadvantages that can be anticipated to happen randomly. Being creative takes people into the world of exploration and imagination, an instance that cannot determine whether our minds are always right (Yadgarovna & Husenovich, 2020). Employees’ minds can be unstable in specific processes and make petty or undesirable decisions. Eventually, having skilled labour means the skills are incorporated in employees’ minds that are severely impaired by mood swings and depression. Consequently, BMW’s utilisation of creative solutions did mean it will always be right to utilise it as a working weapon when similar situations wave.

Sustainable Leadership Practices

For any organisation, the leadership department has become an inevitable section that must be addressed regardless of the organisation’s level and size. Conspicuously, any organisation’s success or failure lies in the hands of the leaders entitled to the organisation (Iqbal & Ahmad 2021). An organisation can either have non-sustainable or sustainable leaders. Sustainable leaders are goal-oriented personnel with micro and macro perspectives of the organisation. Sustainable leaders build communities and initiate stakeholder collaboration to develop long-term values because they consider their entity interdependent (Iqbal & Ahmad 2021).

In contrast, non-sustainable leaders are highly seduced to achieve short-term benefits to investors and petty bonuses to senior executives. Iqbal and Ahmad (2021), clarified that sustainable leaders are highly socially responsible and eager to protect any stakeholder incorporated into their industry. However, sustainable leaders are highly costly compared to non-sustainable mainly because their wages are relatively high as they correspond to the services they manipulate to the organisation.

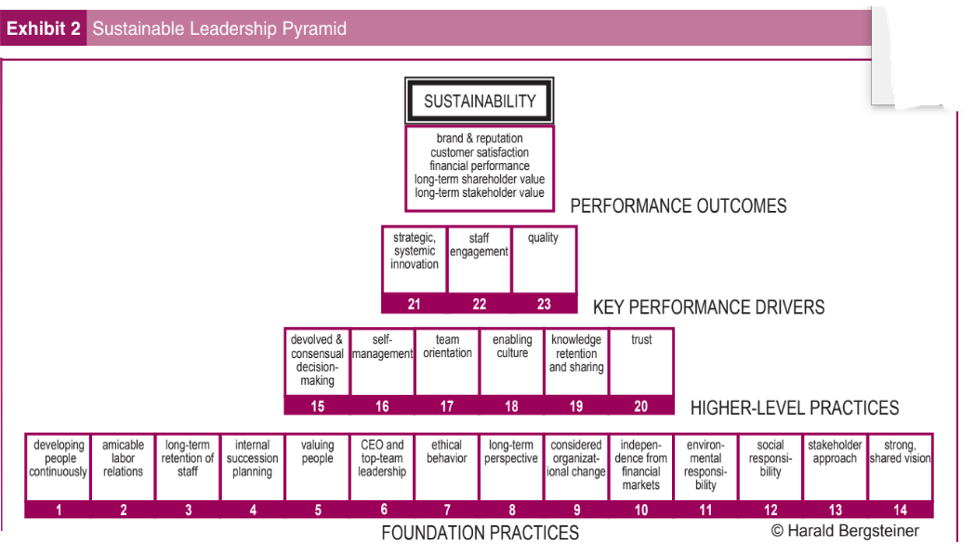

According to Avery and Bergsteiner (2011), BMW Inc. sets an excellent example of entities that have survived severe recession periods courtesy of deploying sustainable leaders over the decades. In BMW, leaders can be categorised into four interdependent groups: foundation practices, higher-level practices, key performance drivers, and those engaged in performance outcomes (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011).

Foundation Practices

In reference to Avery and Bergsteiner (2011), the foundation practices are composed of lower-level leaders who are fully engaged in the company’s internal affairs, and the management can embark on any time of their choice. The fundamental issue of the foundation practice is developing employees continually. BMW has taken it as a responsibility and role to train its employees as an act of developing workers, staff members and special groups (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011).

Besides, all stakeholders, such as suppliers, are entitled to special teaching programs that wave consciousness on the features of the new products and how cars are produced (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). Reaching all local and foreign consumers for teaching poses several difficulties; therefore, incorporating some education into marketing and advertising programs reaches millions of thousands. For instance, in 2010, the entity invested $181 in workers’ training (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). To evade cases of exploiting and maintaining employees’ standardisation, BMW launched amicable relations with labour and federal governments in diverse markets (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). Moreover, BMW has strived to retain its past experienced and skilled workers through succession sanctions of promotions by sourcing employees from the firm. BMW has taught its leaders to be competent in various ways. For instance, an organisation leader must have good communication skills (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). Communication is more than talking fluently but about the right thing at the right time.

Although the issue is highly constrained by communication barriers that make the strategy seem expensive, BMW has experts from various foreign markets that encounter the issue (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). An effective leader is highly intertwined with effective communication. Therefore, as a leader, one must be influential to his/her subordinates in various orders mandated by the management. In BMW plants and premises, discipline is non-negotiable. BMW has undertaken different steps to develop an ethical environment and initiated responsible governance (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011).

Additionally, BMW launched an ethics advisory committee that employees and other stakeholders can report to in case of misconduct. Nowadays, organisational change has advanced to become a non-negotiable strategy, especially in the Artificial Intelligence (AI) evolutions. Like other automobile companies, BMW must employ AI robots in production sites to cater for costs and speed issues and enhance standardised production quality (Zhao et al., 2019).

Besides, BMW has employed AI innovations in the entire supplier chain systems to; enhance accurate goods management, timely deliveries, end-to-end visibility, warehouse efficiencies, and quick and intelligent decision-making processes (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). However, organisational change is highly depicted with varied complexities that have severely posted BMW into future uncertainties. For instance, for BMW to accept any change, there is usually a need for a clearer vision of the change deployed. In cases posed by the issues of GFC, BMW was uncertain for how long the tragedy would persist and how much it could pay the retained employees who had adequate experience in producing (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). When exposed to change, employees usually suffer from change fatigue, an issue that was delayed being diagnosed in most cases. Since its invention, BMW has been environmentally responsible for its conduct, an issue witnessed in its ventures (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). In reference to Avery and Bergsteiner (2011), these programs can be traced back to the early 1970s when they sanctioned an environmental policy within its structural plans and applied it to its entire supply chain systems. For instance, the issue of production and waste recycling has facilitated the exploitation of materials (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011).

In addition, anchoring its supply chain to AI systems has facilitated environmental conservation, like employing conveyor belts, robots, and drones to monitor personnel (Zhao et al., 2019). The utilisation of solar energy instead of fossil fuels has imperatively conserved the environment. BMW values retaining clients the same way it loves client acquisition since all are meant to buy entity products (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). However, not all clients return to buy new products, but others come to buy spares or feedback. In most cases, retained clients have few complaints since they have more or little experience with the company’s goods, an issue that BMW highly values. To keep consumers, BMW has employed varied strategies; has emphasised paving optimistic consumer experience that is met in various ways. For example, it has considered client service critically when making purchases to scrutinise whether they will continue purchasing. Thus, ensure proper and efficient consumer service and encourage them to visit the website to assess; accessibility, usability, and quality.

Moreover, BMW has consumer loyalty programs encouraging clients to make recurring purchases in exchange for rewards (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). BMW has stayed in touch with its clients by frequently consulting them. Unfortunately, retaining clients for BMW has not been an easy strategy, as it has posed some issues. For instance, there are incurring costs for initialising and maintaining retention programs. The programs require an expert staff whom the clients can consult at any time. Therefore, for the consultant, it would be time-consuming and can stay long without being consulted and be consulted often since there are no set schedules.

Higher-Level Practices

Higher-level practice, this group, although interdependent, has set definite roles that make it occupy a central position in BMW (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). The hierarchy initiates the devolution structure of BMW to the foundation level, and it plays a pivotal role in creating consensual decision-making processes. The level paves the roots for self-management since a person cannot manage others while cannot manage himself. This group decides and designs training needs when necessary for the teams. At this level, individual employees are expected to be conscious of the company’s protocols and commercial issues, an issue that can only be possible with a dedicated, skilled, and loyal workforce emphasised on achieving entity goals (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011).

On the other hand, this level is highly dependable on orders and commands from the higher levels that are not guaranteed to be correct. In such situations, one may be mandated to do a well-conscious issue is wrong, but being a path follower must adhere to the command. At some levels, employees can share skills, but with diverse systems, subordinates only follow orders from the seniors, and there is no room to seek help from colleagues other than following the commands (Fransen et al., 2020).

Key Performance Drivers

Key performance drivers are the third-level employees enormously occupied in the macro activities of BMW (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). According to Avery and Bergsteiner (2011), the issues of innovation deployment, quality of goods, and staff engagement are tackled by this group. In reference to Avery and Bergsteiner (2011), at BMW, this level is central, based on consumer experience, and highly integrated into its culture. Innovation plays a significant role in driving an entity’s premium brand strategy; every employee at this level should be innovative (Klein, 2020). BMW tips substantial payments for innovative perspectives catering to working protocols, safety, and efficiency issues. However, the section poses some challenges to the entity. For instance, the department is composed of senior executives who are allocated massive funds to cater to their issues of salaries, allowances and bonus programs (Ries Gisler & Guttormsen, 2020).

Performance Outcomes

According to Avery and Bergsteiner (2011), this level is composed of highly ranked employees who determine the entity’s future at BMW. At this level, the entity is desired to have a considerable brand reputation; consumers are delighted, financial performance is met efficiently, and it caters to matters of long-term shareholders values and long-term stakeholder values of the entity. Being at the top must be sustainable for the entity to remain n competitive in an industry highly depicted with competing rivals. The levels of endeavours in BMW must produce equitable performance outcomes to evade issues of organisational losses that might pertain to the firm (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). The department at BMW is highly responsible for initiating sanctions and guidelines, laying out the firm’s strategic goals and ensuring procedures are followed.

Additionally, it establishes those responsible and has the mandate to hold them accountable for various management systems (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011). Performance outcomes provide accountability for practicality and efficiency in quality management systems in varied ways. For example, quality sanctions and standardised goals are paved for a quality management system. According to Klein (2020) the top management should integrate quality management requirements into BMW’s commercial processes. In addition, top leaders must be risk-takers who employ process approaches and be innovative personnel. Klein (2020) asserted that leaders should ensure the availability of resources that might deny the firm from attaining its objectives efficiently. They should always communicate the significands of effective quality management. Like the subordinates, top management is open to change. When challenges wave, top management seeks possible remedies to cope with the entity’s situation. For instance, they can launch benchmarking schemes that will enable them to realise their strengths and weaknesses pertaining to the company (Klein, 2020). Besides, discussion programs can be scheduled. At this level, the entity is highly constrained by decreased performance levels. Although not highly committed, the available tasks are delicate and should be balanced. There might be poor teamwork between top management and subordinates, an issue that might constrain the entity from attaining laid objectives. Moreover, the level must be occupied by skilled and experienced staff who requires vast salaries and massive allocation of allowances (Klein, 2020). There are issues of scepticism where the employees question the transparency and accountability of the top management in the entity.

Conclusion

For any firm to proper in all its endeavours efficiently and effectively, it must predominantly employ leadership personnel and principles. Notably, the success or failure of commercial entities lies in the hands of the leaders, who, in response, must be competent by all means. To be regarded as a capable leader, one must conceive all leadership skills and principles, which can be recognised when in action. Therefore, organisations must have willing and energetic leaders who are always dedicated to achieving laid objectives. Courtesy of deployment of competent and skilled personnel has enhanced BMW to prosper and remain competitive for several decades, despite being hit severely by economic crises. BMW has strived hard and, in response, remained competitive. For instance, during the financial crises, such as GFC that occurred prior to 2010, BMW has maintained its sales due to the employment of various strategies; keeping competent and skilled technicians, not renewing temporary contracts, collaborating with the national government in paying wages for the company employees, and being innovative in its production. Moreover, BMW was eager to retain old clients like it was to acquire new ones. Similarly, retaining customers took work for the entity, as it was costly.

References

Avery, G.C. and Bergsteiner, H., 2011. Sustainable leadership practices for enhancing business resilience and performance. Strategy & Leadership, 39(3), pp.5-15.

Avery, G.C. and Bergsteiner, H., 2011. How BMW successfully practices sustainable leadership principles. Strategy & Leadership, 39(6), pp.11-18.

Samimi, M., Cortes, A.F., Anderson, M.H. and Herrmann, P., 2022. What is strategic leadership? Developing a framework for future research. The Leadership Quarterly, 33(3), p.101353.

Bass, B.L., 2019. What is leadership? Leadership in Surgery, pp.1-10.

Balasubramanian, T., Dhanalakshmi, N., Saravanakumar, A.R., Paranthaman, G., Manikandan, M. and Chinnappar, G., 2020. Mahatma Gandhi’s life and freedom struggle. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University, pp.927-941.

Haque, I.U., Rashid, A. and Ahmed, S.Z., 2021. The role of the automobile sector in the global business case of Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of International Affairs, 4(2).

Jain, K. and Siddiqui, M.H., 2022. The bigger fall: COVID-19 vs global financial crisis (08-09) impact on Indian MSMEs. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(2), pp.2570-2584.

Brassington, F. and Smith, A., 2000. Competitions and problem-based learning: The effect of an externally set competition on a cross-curricular project in marketing and design. Educational Innovation in Economics and Business V: Business Education for the Changing Workplace, pp.187-208.

Moellers, T., von der Burg, L., Bansemir, B., Pretzl, M. and Gassmann, O., 2019. System dynamics for corporate business model innovation. Electronic Markets, 29, pp.387-406.

Wiprächtiger, D., Narayanamurthy, G., Moser, R. and Sengupta, T., 2019. Access-based business model innovation in frontier markets: Case study of shared mobility in Timor-Leste. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 143, pp.224-238.

Krasheninnikova, E., García, J., Maestre, R. and Fernández, F., 2019. Reinforcement learning for pricing strategy optimisation in the insurance industry. Engineering applications of artificial intelligence, 80, pp.8-19.

Yadgarovna, M.F. and Husenovich, R.T., 2020. Advantages and disadvantages of the method of working in small groups in teaching higher mathematics. Academy, (4 (55)), pp.65-68.

Iqbal, Q. and Ahmad, N.H., 2021. Sustainable development: The colours of sustainable leadership in learning organisation. Sustainable Development, 29(1), pp.108-119.

Zhao, Y., Li, T., Zhang, X. and Zhang, C., 2019. Artificial intelligence-based fault detection and diagnosis methods for building energy systems: Advantages, challenges and the future. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 109, pp.85-101.

Fransen, K., Haslam, S.A., Steffens, N.K., Peters, K., Mallett, C.J., Mertens, N. and Boen, F., 2020. All for us and us for all: Introducing the 5R shared leadership program. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 51, p.101762.

Klein, M., 2020. Leadership characteristics in the era of digital transformation.

Ries Gisler, T. and Guttormsen, S., 2020. Advantages, disadvantages and barriers to changing continuous professional development (CPD) for registered nurses in Switzerland. Perspectives of experts in nursing education and nursing management: First results of a mixed methods study.

write

write