Overview & Introduction

Bernard Chaus, Inc. creates and markets women’s clothing under several trademarks. Made mainly in Asia, they are available in over 4,000 department shops across the United States (Davenport et al., 2012). Many firms started to struggle in 2008 due to the global financial crisis and economic slump. At this point, merchants began having trouble controlling their margins and inventories. As a result, they started to pressure their suppliers for advice on trends and shipment changes. To build their replenishment plans, a company like Bernard Chaus would get information from factories and customers via regular phone conversations at the time (Davenport et al., 2012). Hence, this was vague Regarding identifying particular stock-keeping units (SKUs) in more demand than others. For example, it might be possible to identify a style, but only sometimes, the specific color or size of the style was in high demand. The Bernard Chaus leadership promptly took action to identify the issue and find a remedy.

Identifying A Problem

Retailers were impacted by consumers’ reluctance to spend money during the recession. Various merchants started to pressure their suppliers to supply data analytics, such as which products are selling well, which ones should be discounted, and how much of an item should be provided depending on that information. It has been an issue since Chaus’s primary method of receiving data flow was through weekly phone conversations. Software that could monitor sales data, freight information, seasonal trends, and other descriptive analytic metrics in almost real time was implemented to respond to an issue discovered. Therefore, this system would allow the sending and receiving essential data at every level, from Chaus’ factories to retail outlets. CIO Ed Eskew decided to locate the company’s best data analytics software option as it was the solution.

Understanding the Fix

Primarily, getting a thorough grasp of the company was the first stage in Eskew’s selection procedure. He contacted business unit presidents and their subordinates to ascertain the data needed to enhance the supply chain (Davenport et al., 2012). As he was effectively creating a tool and a database, both of which might be challenging to deploy if they are not well welcomed by the end users, this was an excellent answer to the problem. In order to build a solid rapport between Chaus and its clients and foster trust that would ultimately be advantageous in its own right, Eskew made sure this tool was developed by and for the end-user before employing a software vendor. After that, the merchants took the initiative to recognize internal issues and asked for the tool to help them develop fixes. As a result, this is one of the initial phases in building an effective database (Storey et al., 1997). Therefore, by then, Chaus’ clients knew a remedy was in the works and could let their staff know it would need more time to arrive.

Executive Support

The other executives’ backing was the next thing to do. A corporate choice needs support from the top to last. Gaining the backing of the program’s senior executives gives lower-level staff members the impression that their work is valued and beneficial to the company (Saiyed, 2019). It does not take long for a project to collapse when company executives cast doubt on it. The chief executive officer and chief financial officer saw Chaus’s problems. After presenting them with his thoroughly studied perspective on data analytics, they agreed to help him locate a program that would help with tasks like seasonal sales forecasting and factory communications. Eskew’s continued project leadership is approved by the senior executives as well.

Picking the Vendor

Eskew needed to choose the right provider after gathering data and requirements from his clients and getting approval from his leadership. Therefore, this prompted the third phase to rank the criteria the suppliers had to fulfill to be considered for this project. The first was the capacity to store and provide easy access to past data. Thirdly, the software company’s prior expertise in the retail industry; and secondly, the startup and implementation expenses of the program (Davenport et al., 2012). Although assigning these three criteria the highest priority was a bold move, it was the right one, as the tool became a huge success. Even though these three factors rank highest, other factors also influenced the choice. Eskew was determined to work with a vendor that could develop a solution that would deliver precise data regarding manufacturing and sales, together with shipping considerations, in a timely way. Eskew chose SKYPAD, a retail analytics and business intelligence platform, after a rigorous evaluation.

Implementation

Chaus’s approach was effectively facilitated by the database tool SKYPAD. It could get data from emails, images, Excel files, and other sources. Chaus chose SKYPAD as their provider, and in three weeks, they had a product that all of their merchants could utilize. This tool was a prototype with only the components necessary to address the issues. From the beginning, the tool was a huge success. Before SKYPAD was used, one of the problems that were found early on was that during the weekly phone talks about supply, a retailer might say that a particular dress was selling well, but what they meant to say was that a particular color of the dress in a particular size was selling well. As a result, this created somewhat false information (Davenport et al., 2012). Retailers, Chaus, and its warehouses could see precisely which SKUs were selling—or not—and where they were selling with the help of this new technology.

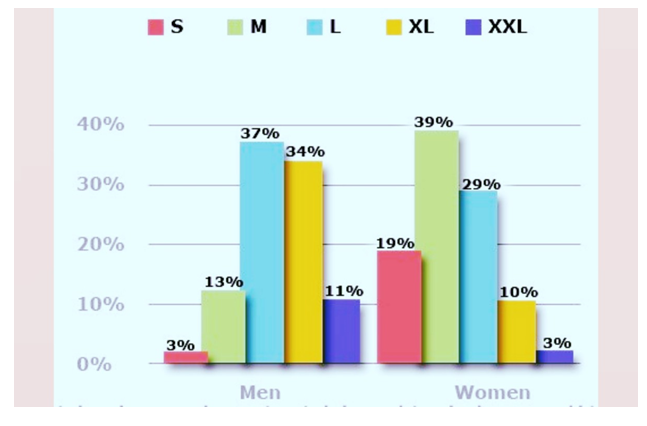

Figure 1

The graph below illustrates how products are sold according to size and gender.

(O’Dell, 2014)

The end users were pleased with the outcomes, and Eskew improved the program’s quality of life over time by adding choices and adjusting the user interface. Launching the tool as a prototype rather than a full-fledged application was a wise decision to avoid overwhelming users and foster an atmosphere where helpful criticism for their particular circumstances could be readily provided.

Post-Production

After SKYPAD was implemented, Bernard Chaus started to reap the rewards even in its most basic version. There were now weekly meetings where the main objective was identifying ways to reduce costs. Users trusted SKYPAD because they were involved in its development. Chaus collaborated with business units that consistently utilized the product with minimal resistance. Davenport et al. (2012) used SKYPAD to stay on top of demand planning, operational efficiency, sales trends, and predictive analysis. Chaus was also able to handle their end-of-season inventories by recommending discount timing to merchants using the program. For their seasonal trend research, several of the business divisions only rely on Chaus. Eskew deserves credit for this confidence during the tool’s creation process. Chaus has been the go-to business for new challenges because of Eskew’s one-on-one interactions with clients. Regarding quantifiable measures to assess whether this initiative was successful, it is projected that using SKYPAD has saved Bernard Chaus upwards of $1 million in freight expenses and decreased markdowns. However, the tool’s development costs were around $50,000. By cutting its quarterly sales revenue losses from marked-down inventory by approximately 50% over the previous year, Chaus was able to enhance margin performance in the first year, according to IBM (2010).

Conclusion

Bernard Chaus set out to address the deficiency in their present data-collecting process, which they recognized needed to be improved. Ed Eskew went out to comprehend the industry and obtain firsthand feedback from those directly accessing the data. Hence, this is significant because it indicates that the software solution and requirements would provide the intended outcomes since the data would be what people who require it would need. For data to be used successfully in business, the intended impact must drive the strategy for integrating and implementing data and technology. Put differently, a company has to establish clear business objectives before deciding which software would best help it reach those objectives (Heidrich, 2016).

Moreover, Eskew established specifications for the software pertinent to Chaus once the critical performance indicators (KPIs) were established, and he was tasked with locating the appropriate software. Eskew anticipated that there would be less of a learning curve for the software by mandating that the software provider have prior expertise in a retail setting. Choosing two software programs that worked well together allowed the right people to move freely and access the data. Therefore, this made it possible to achieve significant savings swiftly. Eskew’s method made sense since he consulted the employees who would be using the information and program he chose. Therefore, this made the program functional and enabled it to meet KPIs even in the most basic version of SKYPAD. Then, Bernard Chaus will continue seeing supply chain enhancements and earnings by hosting weekly meetings to discuss new business prospects.

References

Davenport, T. H., Barth, P., & Bean, R. (2012). How big data is different. MIT Sloan

Management Review, 54(1), 43-46. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-

com.ezproxy2.apus.edu/scholarly-journals/how-big-data-is-

different/docview/1124397830/se-2?accountid=8289

Heidrich, T. (2016). Exploiting Big Data’s Benefits. IEEE Software, 33(4), 111–116.

https://doi.org/10.1109/MS.2016.99

IBM Solution Keeps Bernard Chaus Fashion Operations Moving Forward. (2010, November 18). Retrieved from https://www-03.ibm.com/press/us/en/pressrelease/33031.wss

O’Dell, C. (2014, June 9). Bernard Chaus, Inc. Prezi. Retrieved from

https://prezi.com/isv06fzb4mi6/bernard-chaus-inc/

Saiyed, A. A. (2019). The role of leadership in business model innovation: A case of an entrepreneurial firm from india. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship, 22(2), 70-

88,70A. doi: http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy2.apus.edu/10.1108/NEJE-08-2019-0040

Storey, V.C., Chiang, R.H., Dey, D., Goldstein, R.C., Sundaresan, S. (1997). Database design with common sense business reasoning and learning. ACM Transactions on Database Systems, 22(4), 471–512. https://doi.org/10.1145/278245.278246

write

write