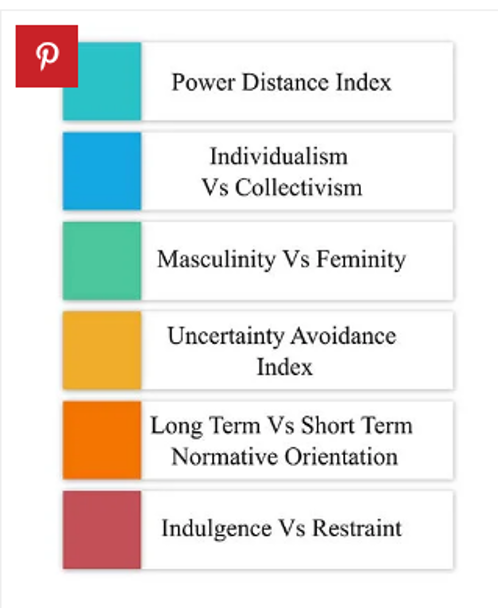

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimension is a helpful model for understanding cultural variations in countries. It is an analytical criterion that offers six dimensions, as shown in (Figure 1) for assessing business situations. Businesses focus on economic, political, and social or cultural contexts when outlining management and marketing strategies generated by Hofstede’s Model (Kang et al., 2021, p2). Scholars factor in behavioural diversity to study marketplace practices to assist businesses with information in global integration (Masuda et al., 2020, p2). Luxury brands constitute a group of commodities and services that require a careful assessment of the market situation. As part of international brands, the consumption of luxury products is also influenced by consumer behaviour and preference (Kang et al., 2021, p2). The paper analyses the cultural situation in African nations in the six domains of Hofstede’s Cultural Model (Figure 2) to recommend whether renowned luxury brands in industries like fashion and automobile can expand into the continent.

Figure 1: Illustration of Hofstede’s Model (Nickerson, 2023)

Figure 2: Hofstede’s Six Dimensions of Culture (Nickerson, 2023)

The first determining dimension is Individualism Vs—collectivism in society. The domain refers to the level of unity and harmony among groups. Africa was traditionally a collective society but has shifted to individualism due to globalisation (Olowookere et al., 2021., p261). Therefore, it implies that individual behaviours influence decision-making. For instance, Nigerian work culture is aligned with the US culture of individualism despite their collective nature (Olowookere et al., 2021., p2). Consumption of luxury products and spending habits is a normative influence based on an individual’s decision to adapt to what others do or consume (Kang et al., 2021, p2). It is based on personal choices as people become more interested in meeting their goals (Gilboa and Mitchell, 2020, p3). Thus, the African context favours the expansion of luxury into the continent.

The second dimension is the power-distance matrix. The aspect deals with the perception of inequality in society (Masuda et al., 2020, p5). Africa has a centralised system of governance with a leader at the top, and the chain of decisions flows downwards (Karlsson, 2016, p13). African culture, for instance, is high power distance as it observes autocracy (Karlsson, 2016, p19; Olowookere et al., 2021., p263). High power distance cultures prefer luxurious brands due to personal lifestyles. Moreover, personalisation has become the new order in luxurious brands such as fashion industries as customers strive to meet personal values (Gazzola et al., 2020, p4). Consequently, luxurious brands can penetrate African cultures due to this shared demand.

The third dimension is masculinity vs femininity which considers how society values feminine and masculine roles. Masculine organisations prefer strengths, assertiveness, courage, and competition, while a feminine community works on softness, nurturing, and quality of life (Nickerson, 2023). African culture is perceived to be feminine as it considerably undermines its effectiveness and strengths (Karlsson, 2016, p20). Such a culture is ideal for luxurious commodities from more developed economies like Europe, America, and China. As a result, the culture opens opportunities for expansion for luxury brands like jewels and electronic vehicles manufactured out of Africa.

The uncertainty avoidance index is the fourth determinant of expansion into the African economy. The dimension determines how cultures accommodate ambiguity (Olowookere et al., 2021., p262). African context has moderate ambiguity acceptance (Karlsson, 2016, p20). It implies that it only readily accepts changes, such as introducing newer commodities. In addition, the culture is prone to explicit and long trade agreements that negate the penetration power of luxurious items. Accordingly, luxury brands are likely to face difficulties entering such a market.

The fifth determining dimension in the expansion quest is the long-term vs. short-term normative orientation. The extent assesses where the culture of a nation is focused on the future or current successes (Nickerson, 2023). Africa has a moderate normative orientation as it has long-term and short-term plans (Olowookere et al., 2021., p262). For instance, Nigeria is second after Japan, while the US is third in being future-oriented (Olowookere et al., 2021., p262). Notably, the culture is open to future innovation while supporting current plans such as consumption. Thus, the economy welcomes luxurious brands that intend to expand into African nations.

The last dimension of the model is indulgence vs. restraint. The aspect describes the ability of society to meet its desires (Nickerson, 2023). African culture has little control hence high indulgence (Olowookere et al., 2021., p262). The culture does not restrict, enabling Africans to buy impulsively to satisfy their desires (Karlsson, 2016, p15). Since luxurious products such as jewels can be purchased without plans, Africans can be easy targets in such marketing plans for responsible companies. Therefore, luxurious commodities can quickly expand into the economy.

Five of the six dimensions indicate that the African culture supports expanding luxury products into the economy. Moderate ambiguity is the only exclusion. Nonetheless, the other five outweigh its influence. The culture confirms that Africans are individualistic, have a high power index, and can spend based on individual decisions and value preferences. Also, Africans are more feminine, meaning they prefer quality products from other nations. Moderate normative orientation and high indulgence jointly indicate that the economy is free to accept luxurious brands due to a desire for innovative products and little control over consumption. Accordingly, African culture allows the expansion of luxury brands.

References

Gazzola, P., Pavione, E., Pezzetti, R. and Grechi, D. (2020). Trends in the Fashion Industry. The Perception of Sustainability and Circular Economy: A Gender/Generation Quantitative Approach. Sustainability, [online] 12(7), p.2809. doi https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072809.

Gilboa, S. and Mitchell, V. (2020). The role of culture and purchasing power parity in Shaping mall shoppers’ profiles. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 52, p.101951. doi https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101951.

Kang, I., Koo, J., Han, J.H. and Yoo, S. (2021). Millennial Consumers Perceptions on Luxury Goods: Capturing Antecedents for Brand Resonance in the Emerging Market Context. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 34(2), pp.1–17. doi https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2021.1944832.

Karlsson, M. (2016). Africa: Open for Business. Exploring the dynamic business culture of sub-Saharan Africa from the perspective of Swedish firms. pp.1–83.

Masuda, T., Ito, K., Lee, J., Suzuki, S., Yasuda, Y. and Akutsu, S. (2020). Culture and Business: How Can Cultural Psychologists Contribute to Research on Behaviors in the Marketplace and Workplace? Frontiers in Psychology, 11. doi https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01304.

Nickerson, C. (2023). Hofstede’s Cultural Dimension Theory and Examples. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/hofstedes-cultural-dimensions-theory.html

Olowookere, E.I., Agoha, B.C., Omonijo, D.O., Odukoya, J.A. and Elegbeleye, A.O. (2021). Cultural Nuances in Work Attitudes and Behaviors: Towards a Model of African Work Culture. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 10(2), p.259. doi https://doi.org/10.36941/ajis-2021-0056.

write

write