Abstract

Background

Sustainability has raised significant interest among business stakeholders and led to the adoption of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) principles in business management. While ESG is relatively new, ESG investment has rapidly increased globally, especially in Asia Pacific regions. As firms adopt sustainable business practices, governments also play a vital role in incentivizing ESG investments and expanding the ESG market. However, ESG has also raised concerns over greenwashing as it presents companies with opportunities to publish insincere and misleading ESG accomplishments that stakeholders cannot verify.

Objectives

This dissertation aims to analyze ESG trends in the Republic of Korea and explore how companies in South Korea have adopted ESG practices and methodologies as part of helping the nation realize its commitment to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDG).

Methods

This dissertation relies on secondary data published by companies in South Korea and a literature review on the topic.

Results and Conclusion

Korean firms are rapidly adopting ESG management principles, with the government expanding the ESG market. However, there are cases of greenwashing due to coal-generated electricity and fossil fuels that are major sources of pollution. Korean firms demonstrate a higher commitment to ESG but focus more on the environmental aspect, potentially ignoring social and governance practices. This dissertation concludes that Korean firms must continually adopt ESG practices to support Korea in achieving a carbon-neutral goal.

Keywords: United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (U.N. SDGs), Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG), Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), Climate Action, Socially Responsible Investing (SRI).

1. Introduction

The rise in environmental and social movements has increased public awareness of the potential impact of corporations on the world they operate. Issues such as human right violation, climate change, social inequalities, and pollution have sparked the need for corporations to actively participate in findings solutions to such challenges. Ultimately, corporations have realized that such issues directly impact their future business operations and could pose significant risks to their supply chain and profitability. Wales (2013) purports that the capitalist system is under siege as corporations are blamed for social, environmental, and economic problems. Therefore, corporations know the need to broaden their organizational goals beyond profitability.

Social, political, economic, and environmental concerns, including Covid-19, have provoked corporations to adopt sustainable business strategies that cushion their business from future occurrences of such events. Environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) has emerged as a metric for evaluating socially conscious and sustainable organizations. Wales (2013) asserts that ESG is a metric for building ethical corporate brands with socially desirable behaviors. Including ESG ratings by internal and external stakeholders has also accelerated the adoption of sustainable business strategies that ensure organizations are future-proof or “achieve success today without compromising the future needs” (Wales, 2013). ESG investments have rapidly increased worldwide, especially in Asia Pacific regions. On top of this, ESG investors decide on investing in a particular strategy regarding two main concerns: ethical values (with an impact on the economy, United Nations Sustainable Development Goals) and the need to manage and alleviate long-term risks (Environment, Social, and Governance, ESG). Thus, integrating ESG standards into investments maximizes long-term returns by minimizing company exposure to risks.

Problem Statement

Increased adoption of ESG standards by corporations has raised debates on their intentions. Studies have demonstrated that ESG marks the emergence of new “green capitalists” who engage in corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a means of marketing brands and making substantive changes to business practices to protect future profitability (Wales, 2013). Like traditional capitalists, green capitalists also masquerade as socially conscious of capturing investors and consumers that share similar values, and thus profitability is the key. Wales (2013) also notes that organizations lay the groundwork to put them in the lead during an economic recession by focusing on sustainability. Undoubtedly, studies have demonstrated a positive impact of CSR on business profitability (Yusoff, Mohamad, and Darus, 2013). Companies that engage in ESG reporting benefit from brand image and reputation, brand awareness, and lower financial risks, which translates to consumer loyalty, cost reduction, employee morale, and higher productivity. Therefore, the findings question the motive for corporations to engage in ESG through the implementation of CSR policies.

Furthermore, de Lange, Busch, and Delgado-Ceballos (2012) illustrate that various driving forces influence corporations to adopt sustainable business practices. The first influence is globalization’s pressure, which increases organizational footprint while exposing organizations to different cultural and ethical values. For example, South Korea is a collectivist state, while the U.S. embraces individualism. Corporations operating in both nations would face cultural challenges that would influence business practices. Furthermore, globalization increases competition and risks associated with different consumer preferences (Guillermo and Elizabeth, 2016). Secondly, corporate scandals such as Enron, Volkswagen, and B.P. Gulf of Mexico oil spills have led to a global media explosion as individuals unite to condemn such actions. Corporate scandals have also raised stakeholder awareness of the well-being of employees, society, and the environment and sparked the need for organizations to prove themselves worthy to the international community. Thirdly, the global economic crisis and pressure from stakeholders, such as shareholders, government, and communities, have forced organizations to revise their business models and consider their impacts on the world. Therefore, organizations could adopt CSR to protect their interests and enhance long-term survival.

Therefore, it is apparent that not all companies that practice ESG do so for the right reasons. ESG provides companies with opportunities to publish insincere and misleading ESG accomplishments that stakeholders cannot verify. The lack of independent verification of ESG reports increases the risk of “greenwashing,” where organizations masquerade environmental soundness in marketing products or brands (Siano et al., 2017). Companies use the “green talk” or decoupling, which involves issuing statements on sustainability and other deceptive communication tactics without concrete action. Hence, companies only talk without any visible action that justifies their commitment to sustainability, thereby capitalizing on the green image. Thus, there is a need to explore the company’s intention of adopting sustainable policies before branding them as sustainable.

Purpose Statement

This dissertation aims to analyze ESG trends in the Republic of Korea and explore how companies in South Korea have adopted ESG practices and methodologies as part of helping the nation realize its commitment to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDG). The dissertation will identify “fake and half ESG” practices in South Korea and potential solutions, especially on the environmental aspect. Therefore, the core purpose is to identify sustainable business practices that ensure a sustainable world.

Delimitations

The scope of this study is limited to the Republic of Korea and will not include other regions in the case analysis. The author chooses South Korea due to the various environmental and climate threats that nations in Asia-Pacific are facing that limit their growth. As noted by Lee and Grimes (2021), South Korea has the potential to emerge as a regional leader in ESG and support sustainable development in Asia-Pacific. Since South Korea is a collectivist society, research suggestions might be inapplicable in other nations outside the Asia-Pacific region.

Structure of the Dissertation

The second chapter will provide a theoretical framework on the background of ESG and define the environmental, social, and governance aspects of ESG. The chapter will also explore various ESG strategies that 21st-century companies have adopted. The third chapter establishes a connection between ESG and United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDG) and explores regulations and guidelines related to ESG. While the section prioritizes ESG regulations and guidelines from South Korea, most of the reviewed guidelines are universally accepted and adopted. The fourth chapter will explore ESG case studies in South Korea’s public and private sectors and identify misusage or false advertisements of ESG business models (greenwashing). The last chapter will provide discussions, recommendations, and conclusions. The chapter will provide solutions to greenwashing techniques and recommendations that Korea can adopt to incentivize adherence to ESG principles.

2. Theoretical Framework

Corporate Social Responsibility

The idea of corporate social responsibility (CSR) traces its origin to Howard Bowen. In 1953, Howard Bowen coined the term corporate social responsibility in his book “Social Responsibility of Businessmen.” Bowen argued that businesses must make ‘desirable decisions that have value to the society (Bowen, 2013). Over the years, Bowen’s idea gained popularity due to various business scandals, including the 1971 Committee of Economic Development Report that exposed poor working conditions in factories, child labor, and the growing economic inequality between employees and capitalists. The Committee of Economic Development introduced the term “social contract” to illustrate that companies do not exist in a vacuum and that organizations are responsible for contributing to society. Since company information is publicly available, increased stakeholder awareness of company operations and potential impacts on the environment and society accelerated the growth of CSR objectives. More companies began investing in society through charitable donations and recyclable materials to package their products. Nonetheless, Bowen’s idea did not get enough attention for about 50 years due to the many insisting on Milton Friedman’s claim.

In 1970, Milton Friedman introduced his theory of corporate social responsibility in an essay titled “A Friedman Doctrine: The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase Its Profits.” Friedman (2007) argued that a corporation’s sole responsibility is to increase shareholder wealth and that corporations are not bound to social welfare. Friedman (2007) based his argument on the nature of corporations. While corporations exist as artificial persons in the law, corporations have no soul and lack moral consciousness. Friedman argued that corporations could not distinguish between what is morally right or wrong unless such distinction is provided by the legal frameworks and policies that organizations must follow. Therefore, the role of corporations is to make profits while abiding by the law.

Friedman also argued that the government is the only institution responsible for social welfare. The government’s role in society is to advance social welfare by reducing pollution, poverty, and unemployment and providing citizens with other necessities, which is the sole purpose that citizens pay taxes. Unlike governments, corporations are not paid to engage in social welfare activities. Doing so is a waste of shareholder’s money, which Friedman terms irresponsible as it violates the agent-principal agreement (Friedman, 2007, p. 175). Therefore, citizens must report social issues like climate change to the government. In contrast, the government conducts a supervisory role on the actions of businesses and individuals without violating individual liberties.

However, increased corporate scandals raised more awareness of the need for corporations to act responsibly. Corporations became aware of their reliance on people and the planet to make profits, which led to the triple bottom line sustainability approach.[1] Further studies revealed that corporations not engaging in CSR find themselves on the receiving end (Burns, 2020, p. 25). Furthermore, various organizations consider company CSR projects while offering financial grants or loans. The International standards organization (ISO) standard 2600 defines CSR as:

Organizational responsibility for the impact of their activities and decisions on the environment and society through an ethical and transparent behavior that: contributes to sustainable development, including health and the welfare of society; takes into account the expectations of stakeholders; complies with applicable law and consistent with international norms of behavior; and is integrated throughout the organization and practiced in its relationships (Bijlmakers, 2021, p8)

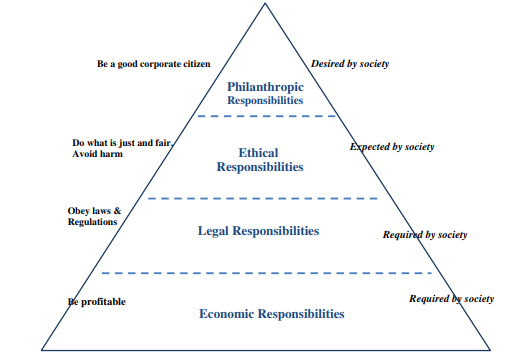

Carroll’s Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility

Carroll (2016, p.5) redefined CSR to include social, legal, ethical, and economic responsibilities that organizations must pursue in the interest of a better society. Carroll (2016) asserts that corporate economic responsibilities are to make a profit for shareholders and produce goods and services that benefit society, which is the primary responsibility of businesses. Legal responsibilities include complying with existing laws to avoid legal battles, while ethical responsibilities entail doing the right thing or acting ethically by conforming to society’s moral values and codes. Social responsibilities for business are optimal but necessary, including corporate philanthropy and other significant social contributions.

Figure 1: The pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility

Source: Carroll (2016, p.6)

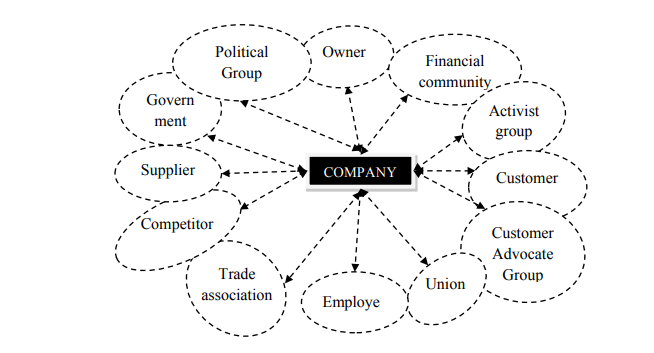

Stakeholder Theory

Stakeholder theory asserts that business values must align with all stakeholders. Business stakeholders include all parties directly or indirectly affected by the business operations. These stakeholders include company employees, consumers, government, shareholders, suppliers, creditors, and society (Freeman, 2010, p.55). Therefore, businesses have an ethical obligation to all stakeholders. The parties have an interest and right to hold the company accountable for its actions and participate in directing the company. Therefore, the theory asserts that businesses have an ethical and moral obligation to maximize human welfare. Doing so strengthens the organizational relationships with stakeholders and ensures sustainability and competitiveness in a complex business environment.

Figure 2: The Stakeholder Map

Source: Freeman (2010, p.55)

Background of ESG

The term ESG (environmental, social, and governance) was introduced in the 2005 “Who Cares Wins” report initiated by the U.N. secretary-general and presented in U.N. Global Compact (International Finance Corporation [IFC], 2005). The report included recommendations for ESG financial markets and investing and the role of governments and regulators in enhancing ESG integration. However, discussions on sustainable businesses for a sustainable world began in the early 1990s at United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro, when UNCED adopted agenda 21 for sustainable development (Lee and Grimes, 2021). The schedule provided an action plan for sustainable development and was adopted by over 174 member nations. Following the UNCED conference, the Commission for Sustainable Development (CSD) was formed in 1992 to ensure follow-up on the agreement and review progress on the implementation of agenda 21.

Three major conventions, including Convention on Climate Change, Convention on Biological Diversity, and the Convention against Desertification, were also established to form the basis of ESG environmental factors (Lee and Grimes, 2021). During the 2004 presentation of the ESG mandate, various stakeholders and scholars contributed to the building block for the new terminology. Porter and Kramer (2011) introduced the idea of creating shared value (CSV) which purports that corporations could balance business and society by investing in products and services that address societal problems. The concept suggests that problem-solving could provide economic value to corporations while producing societal benefits. Examples include recycling, which saves production costs and eradicates pollution. As such, the concept of CSV influenced more corporations to adopt sustainable business approaches with financial and social benefits.

Environmental Pillar

The environmental aspect of ESG investing involves safeguards to the environment and acknowledges the liability of individuals, companies, and nations towards a sustainable “green world.” Human activities are the major culprits of climate change due to increased greenhouse gas emissions, pollution, and deforestation (Lee and Kim, 2022). Environmental sustainability entails responsible use of resources that takes care of the planet and avoid depleting resources. Concerns such as energy use, conservation of natural resources, and environmental pollution increase pressure for organizations to meet present needs without depleting the resources for future generations. Therefore, organizations must consider the impact of their operation on the planet and adopt policies for environmental sustainability.

The Convention on Climate Change adopted a framework to ensure nations minimize greenhouse gas emissions that adversely affect the ecosystem. Following the Paris Climate Agreement, a legally binding international treaty on climate change, over 196 nations agreed to limit greenhouse gas emissions to lower global warming from 2 to 1.5 degrees Celsius. The agreement provoked governments to pass climate and environmental protection laws to curb industrial emissions and accelerate the move to green energy. World governments, including the U.S., further adopted Carbon Taxes to discourage corporations from carbon emissions. Despite the regulation changes, corporations have an ethical responsibility beyond the legal framework to contribute to environmental conservatism.

ESG reporting on the environment highlights various steps corporations have taken to preserve the environment. One of the vital safeguards is the commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by adopting renewable energy, investing in carbon capture technologies, and encouraging employees to use transportation methods with fewer greenhouse emissions, such as using public transport, bicycles, and electric vehicles. Organizations also require suppliers to comply with environmental conservation throughout the supply chain. Secondly, organizations have invested in waste recycling and environmentally friendly packaging materials, such as natural fabrics and plant-based papers. Corporations are also vigilant about waste disposal by reducing solid waste, reducing toxic emissions and water pollution, reducing electronic waste, and establishing a recycling system. Thirdly, corporations conserve natural resources, including reducing water wastage, responsible land use, eliminating deforestation, afforestation projects, and investing in projects that preserve biodiversity. Lastly, green corporations engage in environmental opportunities such as using clean energy, green building practices, and improving energy efficacy.

Social Pillar

Organizational practices have direct harm to employees and society. The social pillar of ESG entails issues surrounding human rights, labor issues, and community relations (IFC, 2005). Organizations have a responsibility to enhance human well-being and evaluate the impact of their product and services on society. Therefore, companies must revise their business practices to identify direct and indirect impacts on human wellbeing. Issues such as employee welfare, respect for human rights, relationships with the community, and socioeconomic inequalities are integral to ESG management.

ESG reporting on social pillars includes organizations’ steps to enhance human wellbeing. Firstly, organizations focus on human capital, which entails employee welfare and labor practices, including employee compensation (equal pay practices), workplace safety and health, employee discrimination, and respect for human rights in contracts with suppliers and other parties in the supply chain. Ethically responsible firms engage in fair labor practices such as paying employees decent wages, fostering equal pay practices, employing women and minorities, and addressing workplace safety issues (Lee and Grimes, 2021). Secondly, organizations engage in product liability, including minimizing social harms caused by their products. Privacy and data safety are also major concerns for 21st-century organizations since data breaches affect consumers. Companies must accept liability for any harm caused by their products and services and take measures to correct such issues. Lastly, organizations focus on fostering social opportunities that enhance equality, including eradicating poverty and providing access to social goods such as electricity, water, healthcare, the internet, and education. Corporate philanthropy such as charitable donations, sponsorships for sports, art, entertainment, and educational endeavors, and cause-related marketing such as pledging to donate 10% of sales proceeds to African development and alleviation of AIDS-related social problems are common social responsibility endeavors that modern companies engage in (Guillermo and Elizabeth, 2016).

Governance Pillar

Governance entails company leadership and management structure that reflects the company’s commitment to transparency. Concerns such as managerial compensation, corruption and bribery, accounting transparency, and board structure are core drivers for governance practices (Lee and Kim, 2022). Consumers and investors are concerned with integrity in corporate governance. They require corporations to be transparent about board diversity, executive pay, anti-corruption practices, competitive fairness, tax practices, and business ethics. Lee and Kim (2022) assert that good governance practices increase consumer confidence, management effectiveness, and workforce productivity.

ESG reporting on governance practices includes the diversity of board members, compensation, tax transparency, financial risks, and anti-competitive and anti-corruption practices. Recently, top executives’ compensation level has raised concerns about organizational compensation metrics based on performance. Such concerns increase opportunities for executives to manipulate accounting data and part with huge bonuses without supporting performance indicators. Company CEOs also receive hefty compensations despite organizations making financial losses. Therefore, a company with good governance practices promotes diversity among board members by providing promotion opportunities to women and racial minorities, disclosing board compensation with pay transparency, and disclosing accurate financial data for all stakeholders.

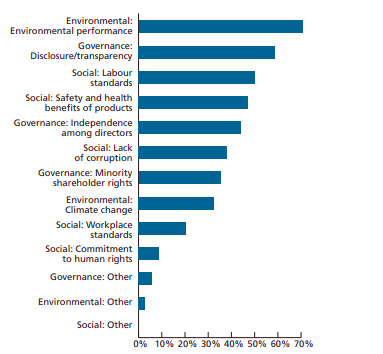

ESG Rating and Transparency

Socially responsible investing (SRI) is expanding as investors use ESG ratings to evaluate investment portfolios. According to OECD (2020), ESG investing amounts to $40 trillion in 2021 and applies to 98% of the Fortune 500 companies. Various institutions offer ESG ratings for investors to consider when making investments. Such firms include MSCI, RobecoSAM, CDP Global Environmental Information Research Center, Sustainalytics, and FTSE Russell. The firm ratings are raked on CCC (weakest) and AAA (strongest), while other raters provide a percentage of ESG risk. The ESG ratings improve company relationships with stakeholders, allow them to gain capital at lower costs in ESG financial markets, and anticipate future risks and opportunities.

However, the use of ESG metrics is a new phenomenon. While investors raise issues related to ESG when selecting stocks, OECD (2020) asserts that there are various challenges with the current ratings. Firstly, the ratings rely on company published data on ESG reports and thus suffer from data inconsistencies. Companies could also provide exaggerated data that provides less weight on the environment’s negative implications. Secondly, different approaches to calculating ESG ratings contribute to the lack of comparability of ESG criteria. Since there are many rating companies, it is challenging to distinguish between quality and ambiguous ratings. Lastly, a lack of transparency in calculations affects the application of ESG ratings when making investment decisions. OECD (2020) asserts that most raters place greater weight on the disclosure of climate-related policies and less on environmental impacts. Therefore, there is a need for standard ESG metrics for easier comparison, including the inclusion of ESG metrics in accounting standards by the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB).

Figure 3: Issues Raised by Investors in Emerging Market Companies

Source: IFC (2005)

3. ESG and United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDG)

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) presented at the 2015 U.N. Sustainable Development Summit are part of the 2030 Agenda and form the framework of ESG. The SDGs provide a solution to grand challenges facing humanity and how they can be addressed through collaborative efforts (Wettstein et al., 2019). The U.N. Global Compact is one of the largest world corporate sustainability initiatives that provides ten principles, policies, and procedures that sustainable businesses must adopt (Hill, 2020). These principles are subdivided into human rights, labor, environment, and anti-corruption.

Human Rights

U.N. declaration of human rights provides a set of legally binding laws that nations must comply with. The inclusion of human rights in SDGs entails corporations advancing human rights and ceasing controversies such as human trafficking, child labor, and negative impacts on employees or human health (Wettstein et al., 2019). The first principle of the global compact is that “businesses should support and respect the protection of internationally proclaimed human rights.” In contrast, the second principle asserts that “businesses must make sure that they are not complicit in human rights abuses.”

Human rights integration in ESG affects environmental, social, and governance pillars. Fundamental human rights relate to grand challenges such as poverty, hunger, inequalities, discrimination, access to education, and even climate change. Since such challenges are connected, organizational practices contributing to climate change could lead to hunger and poverty and violate human rights. Unethical corporate governance practices, such as corruption, could also encourage practices such as labor exploitation, human trafficking, and unhealthy working conditions that undermine the dignity of human life.

Labor

The next four principles relate to labor practices and form the social pillar of ESG. Labor practices such as the unequal pay gap contribute to social inequalities and poverty. Workplace discrimination and harassment of women and racial minorities are major barriers to success. The third principle addresses the need for corporations to uphold freedom of association by allowing employees to join unions for collective bargaining (Hill, 2020). Collective bargaining is vital for employee compensation and remuneration and empowers employees to challenge unhealthy work environments. The fourth principle deals with eliminating forced and compulsory labor, while the fifth principle asserts that businesses must abolish child labor. The last principle under labor asserts that businesses must commit to eliminating workplace discrimination in employment and occupation. Such practices might require organizations to adopt affirmative actions that enable women and minorities to climb the career ladder.

Environment

Principles 7, 8, and 9 detail the need for organizations to adopt UNDEP conventions on climate change and environmental conservancy. Principle 7 asserts that businesses must support precautionary approaches to environmental problems, while principle 8 recognizes the need for businesses to undertake initiatives to protect environmental responsibility. Principle 9 asserts that businesses must “encourage the development and diffusion of environmentally friendly technologies” (Hill, 2020). Environmental principles form the first basis of ESG investing and significantly impact investment decisions.[2] Therefore, organizations have significantly committed to reducing emissions and investing in the environmental conservancy, which generates shared values (CSV).

Governance

The last principle adopted by the U.N. global compact addresses corporate governance and forms the last pillar of ESG. Principle 10 asserts that “businesses should work against corruption in all its forms, including extortion and bribery” (Hill, 2020). While the principle only addresses anti-corruption, ESG requires corporations to practice transparency in governance practices, including disclosure of executive pay, board diversity, and ethical business practices.

Overall, the ten principles of the U.N. global compact are connected to the 17 UNSDGs. The 17 goals include: “ending poverty, ending hunger, health and welfare, education, gender equality, clean water hygiene, decent and clean energy, decent jobs and economic growth, industry and innovation and infrastructure, reducing inequality, sustainable cities and communities, responsible consumption and production, climate action, underwater ecosystems, peace and justice, and partnerships” (Lee and Kim, 2022). Sustainable companies incorporate SDGs in organizational practices through CSR practices. Such practices include corporate philanthropy, employment of women and racial minorities, provision of social goods, use of green and renewable energy, and employee welfare practices.

4. ESG Practices in South Korea

Background

The Republic of Korea (South Korea) joined the United Nations on 1991 and is part of the Paris Agreement. Under the Paris Agreement, South Korea pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 32.5% by 2030 and increase responsible forest and land use (Jeong-Min, 2022). However, Climate Action Tracker (CAT, 2022) rates Korea as “highly insufficient” in speed and stringency of meeting climate commitment.[3] Nonetheless, Korea is progressing in climate action and has adopted various strategies and policies to reduce domestic emissions by 2030. One such commitment was the development of net zero goals when the nation issued a 2050 Declaration of Carbon Neutralization in December 2020 (Lee and Kim, 2022). The Act framework guides public and private sector institutions to reduce emissions. Such guidelines include a commitment to reduce coal-generated electricity, increase the budget for the Korean New Green Deal by 61 trillion won ($52 billion), stop coal financing, and achieve carbon neutrality through the adoption of renewable energy.

Despite being rated poorly by CAT, Korea is progressing towards a net zero world. CAT (2022) reports that Korea reduced the share of coal-generated electricity from 43% to 39% in 2020, although fossil fuels have a larger share (67%) than renewable energy. The government has also required companies to disclose ESG obligations by 2025 and is promoting the adoption of green infrastructure in the private and public sectors (Lee and Kim, 2022). Korean companies have rapidly adopted ESG management standards of drastically reducing carbon emissions and responding to social issues (Jeong-Min, 2022). Increased availability of ESG funds for SRI, including KTB, Koreit, Kiwooom, KB Asset Management, and Korea Investment Management, has provided investors with 382.1 billion won for SRI. Thus, ESG is slowly gaining prevalence in the Korean public and private sectors.

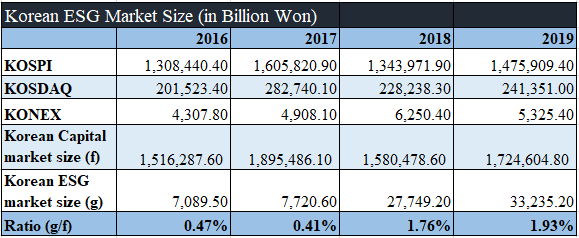

Korea Public Sector

The government of South Korea has committed to ESG principles and great investments in the sector. Korean ESG market has grown from 0.50% in 2016 to 1.90% in 2019 due to government commitment to the new green deal (Lee and Grimes, 2021). ESG ratings are provided by domestic firms such as Korea Corporate Governance Service, Sustinvest, and Daishin Economic Research Institute, and international parties such as Thomson Reuters, Dow Jones, Morgan Stanley, Sustainalytics, and Bloomberg. Lee and Kim’s (2022) evaluation of ESG indicators include:

Environmental

- Carbon Conversion

- Greenhouse gas emissions

- Water resource management

- Waste and pollution

- Natural capital

- Certified eco-friendly products and services

Social

- Labor and income

- Health and safety

- Education

- Residence

- Basic service accessibility

- Information protection

Governance

- Board Structure

- Ethical management

- Compliance with auditing and governance regulations

Public Institutional Investors in Korean ESG

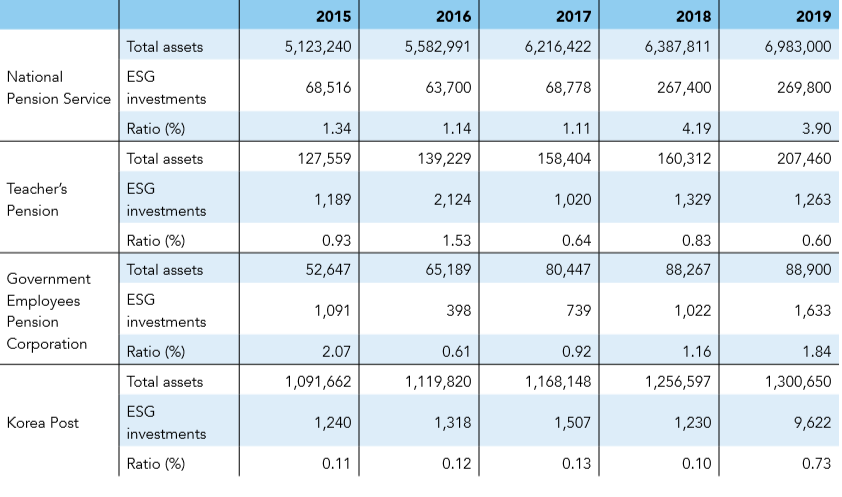

Public institutions in Korea have committed to investing in the Korean ESG market. National Pension Service (NPS) pledged to invest pension funds into green projects and has invested over 269 billion KRW in ESG projects. Other public institutions with excellent ESG investments include Teacher’s pension, Government Employees Pension Corporation, and Korea Post (Lee and Kim, 2022). The investments illustrate the public sector’s commitment to enlarging the ESG sector and serving as an example for private corporations such as Naver, L.G., and Samsung. The growth of the ESG market will contribute to increased adherence to ESG standards by private and public sector bodies. Data on public sector ESG investment is summarized in Table 2 below.

Table 1: Korean ESG Market Size

Source: Lee and Kim (2022)

Table 2: Government Agencies Involvement in ESG investments (figures in 100 million KRW)

Source: Lee and Kim (2022)

Naver

Naver Corporation provides internet services in South Korea and has constructed 5G centers, which are expected to increase their greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption. MCSI Korea ESG index ranks Naver as the top market leader in ESG investing, with an index weight of 10.4% (Son and Cho, 2022). The company receives positive ratings for energy efficiency, empowerment of women and youth, social support during the Covid-19 period, and use of renewable energy. As an ESG market leader in Korea, Naver has issued an $800 million sustainability bond with an ESG rating of AAA.

Environmental Sector

Naver has committed to reducing emissions and achieving zero carbon emissions in 2040. Towards this goal, Naver uses e-contracts to reduce the consumption of paper, reducing emissions and providing positive benefits to forest conservation (Naver, 2021). The company data centers, which are key sources of greenhouse gases, are operated eco-friendly, reducing electrical energy consumption in summer and alternating with renewable and geothermal power. The facility also uses a natural cooling system that allows easier water recycling, reducing energy consumption by 5.86% and greenhouse gas emissions by 6.24% in 2021 (Son and Cho, 2022). The company sustainability report indicates that Naver reduced energy consumption by 37,402 MWh and increased eco-friendly packaging. The company is also committed to green e-commerce, increasing the use of renewable energy and inducing its business partners to participate in environmental conservancy.

Social Sector

Naver generated 4,829.6 KRW billions of economic value for various stakeholders, including partners, employees, government, investors, and local communities. Social ESG commitments include data safety and privacy, stakeholder communication and engagement, digital literacy, and small and medium businesses (SMEs) support. The corporation is also committed to promoting human rights, including allowing employees freedom of association and collective bargaining, providing a safe working environment, responsible management of supply chains, and guaranteeing employee wages and benefits. The company offers various support to employees to achieve work-life balance, including selective and reduced work hours, healthcare, healthy food, daycare center, vacation, financial support, and work engagement support. According to Son and Cho (2022), Naver is committed to enhancing employee diversity, with a male-to-female employee ratio of 63:37 and minimal glass ceiling limitations. 26.9% of female employees occupy leadership roles, while 16% hold executive positions. Naver project flower supports over 450,000 SMEs and has contributed 376.2 KRW billion to over 720,000 participants. Naver is also committed to investing in research and development for social value technologies and providing free digital literacy courses through NAVER Connect Foundation.

Governance

Naver fosters shareholder relationships through regular communications and has a shareholder return policy. The company pays shareholder dividends and stock repurchases annually, with a shareholder return of 30% and a 5% dividend payout. The company also provided sufficient information to investors to protect their rights and introduced an electronic voting system for annual general meetings. The company board of directors consists of 6 males and one female, with a female company CEO and President Choi Soo-Yeon (Naver, 2021). Naver provides a transparency formula for calculating executive pay and bonuses, with the ratio of CEO pay to employee compensation being 75.5:24.5. Naver reports ethical and legal violations and disciplinary actions taken towards employees that violate ethical regulations. In 2021, the company reported six ethical and legal violations, down from 12 in 2020. Furthermore, the company is committed to ensuring diversity in the Board of Directors, protecting data privacy for investors, and using ESG metrics to gauge CEO performance.

Korean Air

Korean Air operates in the unpredictable global aviation industry severely affected by Covid-19. The aviation industry is a major cause of climate change due to greenhouse gas emissions. With 159 air fleets, Korean Air faces the burden of complying with the ICAO Carbon Offsetting and the European Union Emissions Trading System. Still, it has taken steps to minimize its carbon emissions. The company has 23.6% ESG risk, which is a medium risk according to Sustainalytics and ranks 230 out of 359 companies in the Korean transportation industry. The company also receives a positive ranking for ESG risk management and a grade A in Korea Corporate Governance Service’s (KCGS) ESG rating (Korean Air, 2021). The company also issued an ESG bond of KRW 700 billion to purchase eco-friendly aircraft.

Environmental Safeguards

Korean Air is responding to climate change in various ways. The company complied with the existing emission regulations and established an ESG committee in 2020 to formulate strategies for resolving such challenges. The company is committed to reducing fuel and energy consumption and decreasing energy consumption by 28.8% in 2020. Other achievements include stabilizing pollutant emissions by 50%, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and aircraft fuel, and enhancing compliance with environmental laws. The company also minimizes environmental pollution through recycling, noise management, and water treatment of chemical wastes. However, the company operations pose significant environmental threats, and Korean Air lacks a net zero carbon commitment. Strategies to lower carbon include investing in green technology such as eco-friendly aircraft, carbon capture, and sustainable aviation fuel. For example, the company has partnered with Hyundai Oil Bank for biofuel manufacturing and S.K. Energy for carbon-neutral jet fuel (Korean Air, 2021). The company will increase fuel efficiency and carbon emissions through research and development. However, it is challenging to achieve net zero emissions without adopting electric jets, which are dreams of the future.

Social Commitments

Korean Air boosts its response to Covid-19 by ensuring the supply of relief, covid-19 vaccines, and extension of customer flight expiry dates after travel restrictions. However, the company has made tremendous achievements in information security, safety management, talent management, employee welfare, and social contribution (Korean Air, 2021). The company has operated for 20 years in safety management without losing human life despite facing various safety risks. The company has various safeguards to access and minimize risks, respond to emergency calls, and employee response to safety issues. Korean Air also boasts higher consumer satisfaction with zero personal information leakage cases. The company uses technology to enhance consumer experience and alert them on the status of their baggage.

The company has 17,992 full-time employees on employee welfare, with 45% female. Female employees occupy 37.5% of management-level positions and have a retention rate of 90% after childbirth/maternity leave. The company also employs 89% of local individuals in regional offices who occupy 15% of management positions. The company offers free employee training, education scholarships, and competitive welfare and benefits program. 86% of employees are Korean Air Labor Union and Korean Air Pilot’s Union members. On the supply chain, Korean Air has established fair trade guidelines for shared growth and has 275 partners in 19 countries. Lastly, the company has a strong social commitment to volunteering for the community, and over KRW 8,475 million was donated to the community in 2020 despite the business challenges.

Corporate Governance

The company board comprises three internal directors and nine independent directors from diverse backgrounds. Unfortunately, only one board member is female. The company holds regular shareholder meetings, with 12 BOD meetings in 2020. The company has five committees; audit, ESG, compensation, salary, and independent director recommendation committee. The company also announces dividends yearly and has a strong ethical and compliance management system. However, the company does not disclose executive pay and anti-corruption policies, which indicates why the company has a low ESG score despite being an industry leader in ESG management.

Greenwashing

Greenwashing is when corporations exaggerate or misstate their ESG commitment, often underscoring their environmental impact to look appealing (Guillermo and Elizabeth, 2016). Such corporations only describe their CSR commitments with nothing to show, and therefore data provided in the sustainability report cannot be verified by independent stakeholders (Siano et al., 2017). Such scandals, including the Volkswagen case, affect investors’ confidence in ESG ratings, especially since the ratings are provided by various bodies that use different evaluative techniques. Despite companies in Korea adopting ESG management, most companies face controversy over coal-generated electricity and air pollution, which puts Korea at greater environmental risk (Lee and Kim, 2022).

One example of greenwashing is SK E&S Co., Korea’s largest private gas provider. The company has an ESG rating of 28.9 medium risks in Sustainalytics and ranks 49 out of 198 in the refiners and pipelines industry. The company is also rated Baa2 by Moody’s Investors Service. Despite the company’s commitment to sustainability and net-zero emissions, SK E&S Co. operates in a highly risky business industry and has a poor score in managing ESG risks. The company website discusses sustainability, carbon neutral energy, renewable energy, and a green portfolio.[4] However, environmental activists accused the company of greenwashing for the false advertisement of their project in Australia (Lee, 2021). The advertisement labels liquefied natural gas as “CO2” free, alleging that the fuel does not produce greenhouse gas emissions. The company used carbon capture technology for further analysis, which will only capture 60% of the released carbon. The company expects to generate over 1.3 million tons of liquefied natural gas by 2025 from the project, which will leave over 11.4 million tons of carbon in the atmosphere(Lee, 2021). While individuals know there is no carbon-free natural gas, the company deliberately lied to create a “green image.” Therefore, a company that has largely invested in gas and petroleum cannot achieve net zero emissions without changing the line of investment into renewable energy.

The ESG market in South Korea could lead to more greenwashing cases. Controversy on coal-generated power and pollution from construction companies through steel and concrete is a major source of concern. While regulators focus on effort on multinational giants such as Samsung and L.G., other domestic companies might have more opportunities to pollute. For example, G.S. Donghae Electric Power Co., which operates thermal plants, provides images of wind turbines and trees on its website, despite operating a coal-fired power plant in the city of Donghae. Goseong Green Power also operates a coal-fired thermal power facility in South Gyeongsang Province despite using images of lakes, trees, and mountain landscapes to decorate the project outlook.[5] The company also labels itself as an “innovative green power provider” despite opening new coal-powered energy plants that increase carbon emissions. Therefore, such practices illustrate the need for legislators to bar potential pollutant companies from using the label “eco-friendly or green” since it is impossible for such companies to benefit the environment. The only best course of action they can take is to reduce emission levels or invest in repairing the environment.

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

Recommendations

Korea’s public and private sector is rapidly adopting ESG management practices to comply with U.N. sustainable goals. While the nation faces higher environmental risks due to coal-generated electricity, air pollution, environmental pollution, and water pollution due to industrial effluents, continued investment in the ESG market could reshape Korea’s development legacy in the Asia Pacific region. Companies like Naver and Korean Air have made greater commitments to ESG management policies that actively promote environmental, social, and governance practices. Despite such practices, Korea is infested with cases of greenwashing, with major polluting companies labeling themselves “green and eco-friendly.” Korea must actively incentivize ESG investment in the private sector and enhance transparency.

Firstly, there is a need for policy changes to ensure corporations comply with carbon-neutrality policies and other environmental commitments. For example, China also incorporated policies that ensure companies violating existing carbon emission targets are subjected to higher taxes (Son and Cho, 2022). The European Union (E.U.) has also established a financial classification system for sustainability standards, which mandates banning future investments that fail to comply with sustainability standards and makes it mandatory for companies to declare ESG commitments since 2021. Furthermore, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission requires companies that apply for ESG to illustrate specific ESG policies and strategies. Therefore, Korea’s public sector has a role in changing policies to enhance compliance with ESG standards and setting an example for the private sector through green infrastructure.

Secondly, Lee and Grimes (2021) note that ESG metrics and principles are dominated by western institutions, allowing them to potentially profit through ESG evaluation. While capable Korean rating agencies have emerged, the qualitative nature of ESG evaluation contributes to a discrepancy in ratings as indices are prone to risks of lack of transparency due to relationships between rating agencies and the rated company (Lee and Grimes, 2021). The preferential bias also allows larger corporations to prepare data according to the ESG standards and increases the risks of greenwashing. Therefore, there is a need for Korea ESG metric that uses standard metrics for easier comparison. Korea must also support companies with high ESG ratings to sustain ESG market growth through green financing.

Lastly, global companies in western nations have begun to pioneer ESG investing, which must serve as a wake-up call for Korean companies to enhance their progress in adopting ESG management practices. Lee and Grimes (2021) note that most companies have an environmental commitment, precluding the social and governance aspects. For example, only a few organizations have issued social bonds in Korea, with Kookmin Bank and Industrial Bank of Korea issuing $500M social bonds each. Therefore, Korean companies must implement ESG strategies to enhance global competitiveness. Concerns over the lack of governance aspects in Korean ESG further lead to an imbalance in ESG values (Son and Cho, 2022). As such, organizational commitment to ESG must reflect in the organizational code of ethics that reflects employee commitment to ESG issues, performance evaluation for top executives, and supply chain practices. There is a need for accounting standards to also reflect ESG expenditure and therefore allow stakeholders to verify organizational commitments to ESG without relying on third-party raters.

Conclusion

By evaluating ESG practices in South Korea’s public sector and two domestic companies: Naver and Korean Air, it is evident that the adoption of ESG management in South Korea has taken shape. The Korean government has put more effort into incentivizing ESG investment, although there is a gap in sustainable financing for social and corporate bonds. There is a need for more funding that enhances the attractiveness of ESG investing among South Korean firms and policy changes that close the compliance gap. While Korea has required companies to disclose ESG obligations by 2025, there are policy gaps in coal-generated electricity, fossil fuels, and air pollution. Such environmental challenges continue to threaten the sustainability of businesses and increase the costs of climate change. Furthermore, there is a considerable gap in governance practices, especially in anti-corruption policies and executive pay. With increased investor preference for socially responsible investing, Korean firms must lead the expansion of the Korea ESG market and support Korea in achieving a carbon neutral goal.

There are limitations to the two companies investigated in this study as they do not present a clear picture of the Korean economic scene. For example, Korean Air only drives 40% of its revenue from the Korean market. The companies are also deemed to have a major influence on the domestic society and are therefore under the limelight by all stakeholders. Thus, the two companies may differ from smaller companies and SMEs due to their ability to raise lump sum funds and take substantial risks. Such flaws are inherent in ESG studies since ESG management is new in Korea, and there is insufficient data to justify such investments for small firms. Therefore, future studies must overcome such limitations by handling diverse industries and including small domestic companies in Korea.

Reference List

Bowen, H.R. (2013) Social responsibilities of the businessman. Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa Press (University of Iowa Faculty connections).

Burns, P. (2020) Corporate Entrepreneurship and Innovation. 4th eds. London: Red Globe Press.

Carroll, A.B. (2016) ‘Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: taking another look,’ International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 1(1), p. 3. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-016-0004-6.

Climate Action Tracker (2022) South Korea | Climate Action Tracker, Climate Action Tracker. Available at: https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/south-korea/ (Accessed: 16 July 2022).

Friedman, M. (2007) ‘The social responsibility of a business is to increase its profits, in Corporate ethics and corporate governance. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 173–178.

Guillermo, J.C., and Elizabeth, P. (2016) Good Corporation, Bad Corporation: Corporate social responsibility in the global economy. Open SUNY Textbooks.

Hill, J. (2020) ‘Chapter 9 – Defining and measuring ESG performance’, in J. Hill (ed.) Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Investing. Academic Press, pp. 167–183. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818692-3.00009-8.

Jeong-Min, N. (2022) Korean companies rapidly embrace ESG in management standards, The Korean Economic Daily. Available at: https://www.kedglobal.com/esg/newsView/ked202205230007 (Accessed: 16 July 2022).

Korean Air (2021) 2021 Korean Air ESG Report. South Korea: Korean Air, p. 85. Available at: https://www.koreanair.com/content/dam/koreanair/ko/footer/about-us/sustainable-management/report/2021_Korean%20Air%20ESG%20Report_en.pdf.

de Lange, D.E., Busch, T. and Delgado-Ceballos, J. (2012) ‘Sustaining Sustainability in Organizations’, Journal of Business Ethics, 110(2), pp. 151–156. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1425-0.

Lee, E. and Kim, G. (2022) ‘Analysis of Domestic and International Green Infrastructure Research Trends from the ESG Perspective in South Korea’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), p. 7099. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127099.

Lee, H. (2021) ‘Gas Giant in Korea Accused by Activists of Greenwashing’, Bloomberg.com, 22 December. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-12-22/gas-giant-in-korea-accused-by-activists-of-greenwash-advertising (Accessed: 19 July 2022).

Lee, Y. and Grimes, W. (2021) ‘Assessing South Korea’s role in promoting ESG investing in the Asia-Pacific’, Korea Economic Institute of America Academic Paper Series [Preprint].

Naver (2021) Sustainability Report. South Korea: Naver, p. 79. Available at: https://www.navercorp.com/navercorp_/ir/sustainabilityReport/NAVER_2021_ESG_ENG.pdf.

OECD (2020) ESG Investing and Climate Transition Market: Practices, Issues, and Policy Considerations. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, p. 36. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/finance/ESG-investing-and-climatetransition-Market-practices-issues-and-policy-considerations.pdf.

Siano, A. et al. (2017) ‘“More than words”: Expanding the taxonomy of greenwashing after the Volkswagen scandal’, Journal of Business Research, 71, pp. 27–37. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.11.002.

Son, S. and Cho, M. (2022) ‘Effectiveness of ESG Management in Korea Companies’, Knowledge to Lead, 2(1), pp. 346–354.

Wales, T. (2013) ‘ORGANIZATIONAL SUSTAINABILITY: WHAT IS IT, AND WHY DOES IT MATTER?’, 1, p. 12.

Wettstein, F. et al. (2019) ‘International Business and Human Rights: A research agenda’, Journal of World Business, 54(1), pp. 54–65. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2018.10.004.

Yusoff, H., Mohamad, S.S., and Darus, F. (2013) ‘The Influence of CSR Disclosure Structure on Corporate Financial Performance: Evidence from Stakeholders’ Perspectives’, Procedia Economics and Finance, 7, pp. 213–220. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(13)00237-2.

[1] The term “triple bottom line” was coined by John Elkington in 1994. For more information, see https://hbr.org/2018/06/25-years-ago-i-coined-the-phrase-triple-bottom-line-heres-why-im-giving-up-on-it

[2] See Figure 3

[3] To avoid confusion, Korea will refer to the Republic of Korea or South Korea throughout this section.

[4] See https://www.skens.com/en

[5] See http://www.ggpower.co.kr/

write

write