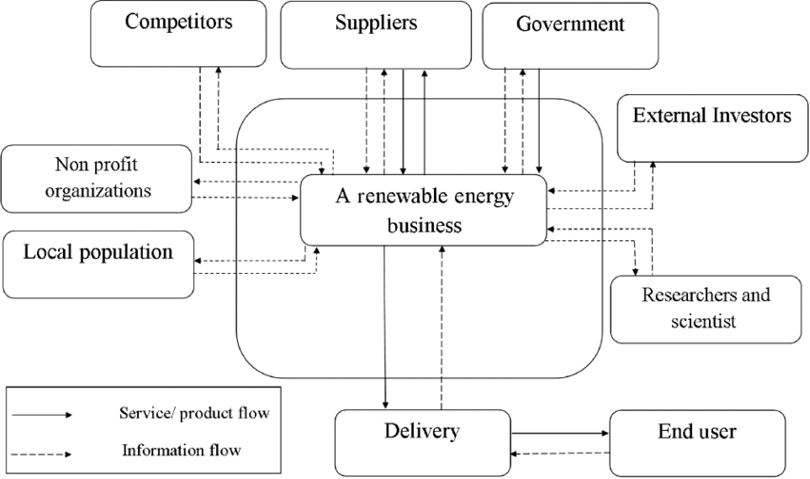

The transiting of urban renewable energy presents an immense design challenge under the simultaneous overall urbanization and sustainable development demand. This paper discusses the stakeholder analysis as part of the Design Thinking process carried out within the complex undertaking. The diversity of viewpoints, interests, and impact of the different stakeholders regarding the urban energy system should be appreciated to resolve this problematic issue efficiently.

A stakeholder map for Urban Renewable Energy Transition is one of the essential utilities that categorize various players, including residents, businesses, etc., based on their influence and interest. This helps in strategic planning and decision-making since it depicts in a visual form the complexity relating to the process of transformation. Through the analysis and prioritization of stakeholders, this tool enhances communication and participation and contributes to the successful integration of renewable energy solutions within cities.

Stakeholder Identification and Prioritization

Understanding the multidimensional aspect of the transition, the stakeholder analysis that we will perform will cover not just the human players but also the role of technology and environment, which is equally important. Stakeholder identification employed a combined method of brainstorming sessions and critical player interviews within the urban energy sector (Sillak et al., 2021). Utilizing categorization, the needed stakeholders were segmented into user groups (residents, businesses), communities (local neighborhoods, NGOs), and systems (energy grids, financial institutions). Prioritization relied on a power-interest matrix, tactically arranging stakeholders depending on their influence and stake in the transition. It zeroed in on the crucial individuals who can control the future course of that method. Prioritizing certain groups was based on their acknowledged influence and perceived interes,t thusfacilitatingn a specific and result-oriented design thinking approach (Binder et al., 2016).

Stakeholder Analysis

Detailed analysis was carried out for each of the prioritized stakeholder groups; their main characteristics, views, needs, and values relevant to the transition were examined.

User Groups:

- Residents: Diversified energy consumption patterns at different levels of environmental awareness, issues about pricing and accessibility of renewables.

- Businesses: Cost-benefit concerns, the desirability of budget-friendly and dependable substitute renewable energy approaches, greenness as an issue.

- Communities:

- Local Governments: Policy formulation, infrastructure development, community participation, and managing the conflicting local resources.

- Neighborhood Groups: Local environmental concerns, job creation/loss, desire for community benefits.

- Systems:

- Energy Grids: Transition to renewable energy, infrastructure refurbishment, and distributed solutions.

- Financial Institutions: Investment prospects, risk assessment, roles in funding renewable energy projects.

- Environment:

- Ecosystems: Renewable energy infrastructurehas potential impacts on biodiversit,and needsd sustainable natural resources management.

- Climate Change: Reducing greenhouse gas emissions, renewable energy as a mitigating factor against climate change adverse impacts.

Empathy maps, personas, and journey maps were pivotal in depicting stakeholder’s understanding. Empathy maps revealed the user’s emotions and experiences, which encouraged the human-centered design approach (Battulga & Dhakal, 2024). Attributes of persona groups were gathered to personalize the perception of stakeholders. The journey maps delineated all the touchpoints and interactions between the stakeholders and the energy transition process.

Engagement Strategies

Recognizing the distinct needs and characteristics of prioritized stakeholders, specific engagement strategies were formulated:

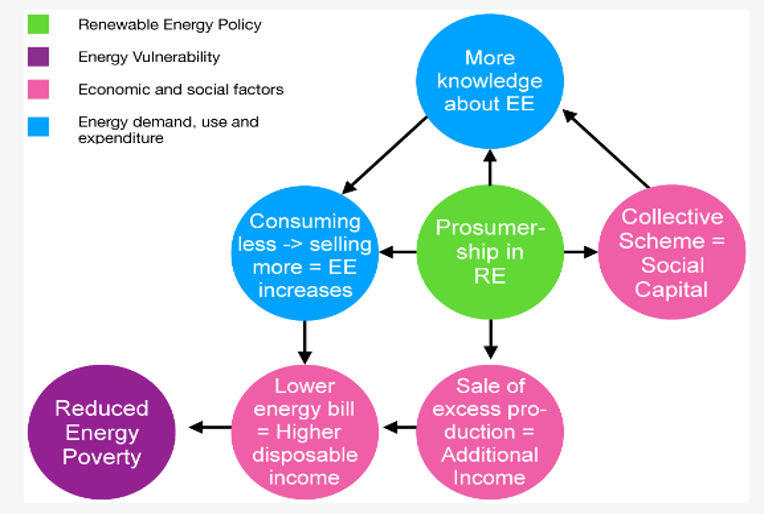

User Groups: Educational discussions and programs promoting knowledge building of renewable energy choices. Financial incentives, and community-based energy sharing programs to reduce cost barriers (Oudes & Stremke, 2018).

Communities: Collaborative planning processes that engage community members in project design and decisions. Local renewable energy projects, including job creation and community benefits.

Systems: Research in cooperation with technology companies for grid compatibility and innovative solutions.

- Policy systems are reinforcing investment in renewable energy infrastructure upgrading.

Environment: Environmental impact assessments and mitigation during project development. Backup for sustainable practices and conservation initiatives aimed at minimizing adverse effects on the environment.

A communication plan promoting transparency will ensure a continuous interaction and feedback loops with stakeholders from the beginning of the design process, the inclusion and flexibility are emphasized.

Conclusion

Such stakeholder analysis offers insight into the multidimensionality of urban renewable energy transition, elucidating a complex network of factors affecting its trajectory. Through the recognition of positions and interests that have human, technological, and environmental ones, we shall be able to go towards the design of feasible and sustainable solutions. While the presented analysis gives relevant information, its drawbacks arethe dynamism of urban systems and the need for constant reevaluation. Further investigation of evolving community dynamics, advancing technologies, and shifting global energy depends on the constant refinement of the design. The stakeholder analysis becomes one of the guiding lights to steer the Design Thinking journey toward a viable future where renewable energy integration is not only within the realm of possibility but also integrally congruent with the multidimensional needs of the urban ecosystem.

Priority setting of stakeholders, in-depth analysis, and customized engagement approaches lead to the emergence of practical and responsible solutions. Nevertheless, the dynamic character of urban systems demands continuous evaluation and improvements. The stakeholder analysis illuminates the journey of Design Thinking, allowing renewable energy to walk hand in hand with the multiple facets of urban development.

References

Battulga, S., & Dhakal, S. (2024). Stakeholders’ perceptions of sustainable energy transition of Ulaanbaatar city, Mongolia. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 189, 114020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.114020

Binder, C. R., Knoeri, C., Bedenik, K., Kislinger, M., Kreuzeder, A., & Vilsmaier, U. (2016). Sequence of transition pathways in energy transitions: The role of end-use technology acceptance, stakeholder analysis and scenarios. Energy Policy.

Oudes, D., & Stremke, S. (2018). Spatial transition analysis: Spatially explicit and evidence-based targets for sustainable energy transition at the local and regional scale. Landscape and Urban Planning, 169, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.07.018

Sillak, S., Borch, K., & Sperling, K. (2021). Assessing co-creation in strategic planning for urban energy transitions. Energy Research & Social Science, 74, 101952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.101952

write

write