Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic caused sudden global disruptions to places and people, with significant psychological, social, and economic effects. Hospitality was one of the most affected industries worldwide throughout the pandemic due to multiple lockdowns and government restrictions. In the UK, the industry was also affected by Brexit, but the end of its period coincided with the beginning of a lockdown, making it difficult to separate the impacts of the two (Hutton and Foley, 2021, n.d). The hospitality industry mainly includes food and accommodation industries, including cafes, Airbnbs, pubs, restaurants, bars, and hotels. The first lockdown resulted in grounded flights restricting the flow of customers in the hospitality business. The lack of business caused job losses, decreased revenue, and worldwide uncertainty.

Hospitality Restrictions

Trading restrictions caused by the pandemic disproportionally affected the food and accommodation businesses. The public was warned against restaurants, bars, and other indoor fun facilities. On March 20, the government ordered the closure of hospitality businesses unless the services were takeaway or deliveries. A few months later, the companies were able to reopen but had to follow the social distance restrictions (Brown, 2021, n.d). This lowered the capacity that a venue can hold hence reducing customers. Also, they were restricted on the meals and drinks served. The England-wide lockdown led to the closure of cafes, restaurants, bars, and pubs, except for takeaway.

For accommodation, leasing an Airbnb house or sharing a rented room through Couchsurfing has become almost impossible due to the new restrictions. A while back, the sharing economy, which the economy has become a crucial element, was expected to grow to approximately $335 billion by 2025. By June 2020, hotel bookings had reduced by 92% instead of February of the same year. Similarly, passenger flow via Heathrow had a decrease of 97%. For a global firm like Hilton, which owns numerous properties across over 100 countries, they experienced an 81% decrease in revenue per available room (RevPAR) in the second quarter. The restrictions that affected accommodation sharing include border closures, flight cancellations, quarantines, and lockdown. On the supply end, statistics show a significant decrease in income for Airbnb hosts. Many employees were laid off staff forced to reduce their revenue forecast. Quarantine and lockdown devastated the physical and digital connection in the sharing economy (Gerwe, 2021, p.120733). While the digital aspects remained unaltered by world events, the physical side of leaving the house, travelling, doing transactions, and entering someone else’s property became impossible. Therefore, even though the guest and the host remained connected, the consumption and distribution of services were unbelievable.

Consumer Demand

Statistics show that the demand for eating out increased relative to 2019 between Monday and Wednesday during the pandemic due to the Eat Out Help out Scheme. By August 31, which was the last day of the scheme, the industry experienced a significant improvement in seated customers instead of the same day a year before. By September, the numbers had dropped to around 10% of the 2019 levels.

The government developed the scheme to support the reopening of the business due to the first lockdown. The strategy aimed to maintain jobs within the hospitality industry by encouraging citizens to eat in hotels and restaurants. The government offered 50% off the cost of meals and non-alcoholic beverages consumed in the hotels and restaurants. Generally, close to £850 million was claimed under the Eat Out Help Out scheme in over 78,000 outlets. The total amount paid was £840 million, caused by errors in payment details and rejected sales. Even though the strategy boosted customer demand, it was dropped when restrictions were re-imposed.

Economic Output

In 2019, the UK economic output of the hospitality industry was over £59 billion, which corresponded to about 3% of the total financial out in the state. About 30% of the total output was from accommodation, while 70% came from food and drinks service. Over 24% of the total production from the whole industry was based in London, while almost 15% was established in the South East. However, the significance of hospitality services to the economic production of each area is similar. They make up to 4% of the entire financial work for each country and region (Hutton and Foley, 2021, n.d).

Businesses

At the begging of 2020, there were over 200,000 food and accommodation businesses, which makes up close to 4% of all businesses. Of these, 10% were employers. 77% includes the food and drink service enterprises, while accommodation took about 23%. London had the highest number of food and accommodation businesses which took about 18%. However, the percentage of hospitality businesses in all regions in the UK was similar, with Wales having the highest balance and Northern Ireland representing the least number. Most hospitality businesses in the UK are small or medium enterprises (SMEs). Close to 135000 employers had small businesses, 3200 had medium-sized businesses, and about 700 were large businesses with more than 250 employees. A 2019 survey showed that hospitality has higher proportions of SMEs than other sectors that women and other minority groups lead.

Business turnover and Trading Status

Hospitality businesses have seen significant effects on business turnover. Monthly business turnover is an essential contributor to the monthly GDP approximation, and hence it observes similar trends as GVA production. Food and accommodation subsectors experienced an increase in turnover in December. Many businesses had to shut down over the festive period in 2020. Statistics show that the percentage of companies trading rose through July since companies were allowed to reopen. About 80% of the food and accommodation companies were still in business during the summer of 2020 before restrictions were re-imposed in October. There was a slight improvement in trading during Christmas, but 2021 saw a decline lower than the paused trading.

During the pandemic, the number of hospitality businesses that had posed trading was higher than most industries in the UK. Between February and March 2021, close to 43% of hospitality organizations in the UK were doing business, 55% had paused, and about 2% had permanently stopped doing business. Between February and March 2021, 74% of companies across all sectors were trading, while only 24% had paused (Hutton and Foley, 2021, n.d). Additionally, the hospitality sector reported low cash reserves, profits, and business confidence. Throughout February, almost 50% of hospitality businesses had reported that 50% lower than expected during that period compared to only 13% of companies in the other industries.

Employment

Employment estimates the number of individuals aged between 16 and 64 years old in paid work. It also includes individuals who are temporarily away from work but expect to return. These are furloughed workers and include those on either maternity, paternity, or annual leave. By September 2020, there are close to 2.4 million jobs in the hospitality sector, representing about 7% of the total UK employment. From 2011 to 2020, the number of employment opportunities significantly increased. By March 2020, the employment rate had reached 2.5 million, the highest record since 1978. By September 2020, the number of jobs had reduced by 147,000.

Labor Markets

Data from the labour market shows a decrease in food and accommodation service industry employees. From January to September 202, workers decreased by about 6%. At this point, the pandemic had not caused the expected unemployment increase. However, this was partly because of the Coronavirus Job Retention plan, as employees on leave are still classified as employed. In terms of ethnic groups, the number of employees from a BAME ethnic background represented over 15% of the employees compared to 13 % of the entire economy.

Among those still employed in the industry, the number of hours they worked reduced significantly between the January-march 2019 quarter to that of October-December 2020. During the first lockdown in the quarter of April-June 2020, the average number of hours worked per week dropped to 13 hours, which is a 54% drop from the same quarter in the previous years. The main reason for this drop is that the industry was completely shut down as directed by the government during most of that quarter. The opportunities for working remotely were limited. There was a 20% decrease in average working hours for all employees during the same period. Three months to December, the number of working hours per worker was more than 18.6 compared to 27.9 hours for the same period in the previous year. The difference is attributed to the lockdown in England from November to December. Pubs, restaurants, cafes, and bars remained closed unless they were doing takeaway (Hutton and Foley, 2021, n.d).

The coronavirus outbreak caused disproportional economic effects on some employees.

Recent statistics show a continued revival of the UK labour market, with indicators showing a return to the pre-pandemic levels. Over the past few months, employment levels have increased while unemployment has hit below the pre-pandemic levels. However, the high inflation and economic inactivity will reduce the real wages of the employees.

Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme

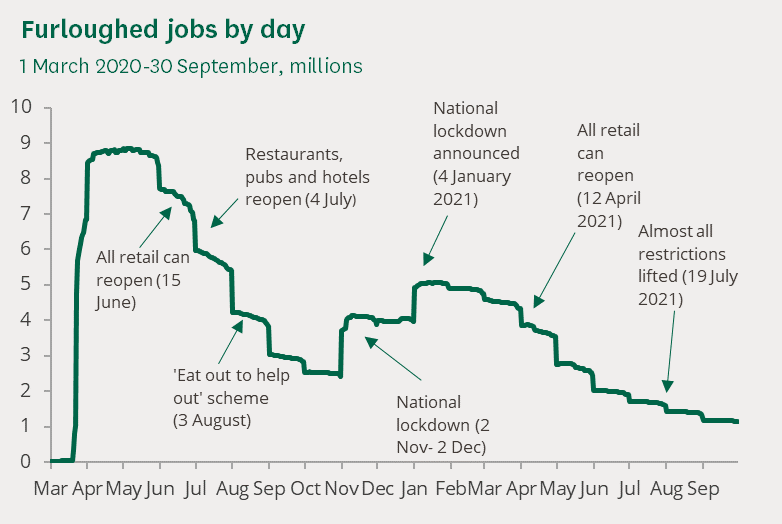

Towards March 2020, the government declared the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS), also known as the furlough scheme. The strategy aimed to offer grants to business owners to retain and pay their employees despite the dreadful impacts of the pandemic. The employment rates on furlough under the CJRS plan in the hospitality industry got to their peak in April, with an estimated 1.6 million jobs on furlough (Hutton and Foley, 2021, n.d). From April to the end of October, the number declined. In September, the decline across all sectors was due to the reduced government assistance toward employee wages in August. There was also a slight decline when the CJRS approached its original end date in October. At this point, some employees would have either come back or left work.

Towards the end of October, the government declared another lockdown across England, which lasted throughout November. They also announced the extension of the furlough plan that was about to end in October. Between October 31 and November 1, furlough jobs increased by over 80%. However, the number slightly reduced between November and December and slight restrictions. At the beginning of 2021, the government announced the third national lockdown. Restaurants and hotels had to shut down, and furloughed jobs in the hospitality sector increased by 7%. This trend was almost similar to all the other sectors. By the end of January, about 1.15 million furlough jobs were available in the hospitality sector (Hutton and Foley, 2021, n.d). The food and accommodation service industry has had increased furlough jobs on the CJRS apart from April and May, where more jobs were furloughed in the retail and wholesale sectors.

Table 1: Jobs furloughed per day in food services and accommodation.

Source: HMRC, HMRC Coronavirus (Covid-19) statistics, 25 February 2021

Through gender, age, and full or partial jobs, Furlough jobs can be analysed. At the end of the scheme, jobs held by individuals over 65 years were more likely to be furloughed than those of younger employees. The same proportion of employment held by women and men was furlough. From the beginning of July, the government partially made the furlough scheme more flexible to be reintroduced. Over the 2020 summer, partially furloughed jobs increased while fully furloughed ones reduced when the lockdown restrictions eased, allowing employees to work sometime. Most employees on leave would have become redundant if the CJRS scheme did not exist. The scheme also reduced the effects of the pandemic on the labour market. November experienced an increase of 257,000 payrolled employees than October. This outcome suggests that the levels of unemployment will be controlled despite the end of the scheme (Hutton and Foley, 2021, n.d).

Conclusion

The COVID-19 outbreak is regarded as the biggest catastrophe of our generation that completely transformed the world in just a few months. The ultimate impact of the pandemic might take a while to quantify as the scars are still fresh. One of the most affected industries was the accommodation and food service industry. The strength of the accommodation and food industry became its weakness during the pandemic (Ntounis et al., 2022, p47). The outcome shows the need to investigate the shifts in behaviour and attitude to prepare for future occurrences like that.

Bibliography

Louis, N., Parker, C., Skinner, H., Steadman, C. and Warnaby, G., 2022. Tourism and Hospitality industry resilience during the Covid-19 pandemic: Evidence from England. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(1), pp.46-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1883556

Hutton, G., and Foley, N., 2021. House of Commons Library briefing paper: Number 9111, March 23 2021: Hospitality Industry and Covid-19 https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9111/CBP-9111.pdf

Brown, J., 2021. Coronavirus: Enforcing restrictions. House of Commons Library. Retrieved on April10, p.2021.

Gerwe, O., 2021. The Covid-19 pandemic and the accommodation sharing sector: Effects and prospects for recovery. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 167, p.120733.

write

write