Abstract

Overview of the Topic

The burden of chronic disease threatens to overwhelm healthcare systems as the population ages. Telehealth may improve care coordination and self-management in older adults, but research outcomes are inconsistent. Clarifying the aspects that influence efficacy can guide nursing practices and policies for strategic implementation.

Aim

This systematic review aimed to identify critical parameters influencing telehealth’s effectiveness in managing chronic illnesses in the elderly to influence nursing care improvements, future research priorities, and legislative reforms.

Method

Following PRISMA criteria, a search of databases such as PubMed and the Cochrane Library for relevant papers from 2018 to 2023 was done. Ten qualitative studies were included based on predefined criteria. Before doing a theme synthesis, two reviewers independently extracted data and assessed quality using the COREQ tool.

Results

Modality, intervention duration, amount of care integration, and personalisation all impacted results. Continuous, coordinated efforts with remote monitoring resulted in greater clinical gains than solo apps. Telehealth improved accessibility and patient/provider experiences, but older users required additional training and assistance. Persistent challenges with the digital gap threatened to deepen disparities. Privacy, security, and virtual therapeutic partnerships were all important ethical considerations. Effective implementation depended on senior-tailored design, hybrid consultation approaches, cultural sensitivity, and continual feedback-based improvements.

Conclusion

Telehealth has the potential to improve chronic disease management in the elderly, but it must be implemented strategically, with a focus on user demands and ethical considerations. Specialised training programs, coordinated care models, patient-reported metrics, and health policies that increase digital literacy and technological access can help elderly populations embrace. More large-scale comparative effectiveness studies on clinical/cost outcomes and self-efficacy implications would add to the evidence base guiding telehealth use in older people.

1.0 Introduction

1.1 Research Background

Telehealth has become a promising way to help older adults better control chronic diseases and coordinate their care as new technologies make it easier to use more of them in healthcare. Many more people are using tech-enabled methods, especially since COVID-19 requires them to be able to work from anywhere in the world. However, there is still a lot of variation in the clinical outcomes seen in these studies. More synthesis is needed to come up with best practices that are based on facts. Growing numbers of older people around the world are expected to make health systems around the world much more overworked. Improving telehealth strategies to help patients take care of their illnesses and regularly check on their condition could be very helpful in this area. Care teams with limited bandwidth can focus on treating the most at-risk patients, leading to better long-term outcomes for the whole population if the right remote tracking and care tools are used on a large scale and work well.

In particular, more than 15 million older adults in Britain currently have one or more chronic illnesses. This puts too much pressure on services that fail to meet the demand because of a lack of clinicians, tight budgets due to austerity policies, and limited beds and infrastructure (The Kings Fund, 2022). Comorbid patients often need care coordination across multiple fields. This can lead to care fragmentation, less-than-ideal outcomes and unnecessary hospitalisations during transitions. Telehealth can potentially improve the quality of life and sense of self-efficacy for seniors with higher needs while reducing costs and system overload on a larger scale if it can help patients live healthier lives and spot symptoms getting worse early on (Xiao and Han, 2022). In reality, though, clinical studies show mixed results, with some groups seeing better outcomes and others not changing. This shows that the effectiveness of the intervention is different for everyone.

To successfully target interventions that balance patient needs with cost-effectiveness for large healthcare payers, it is still necessary to clearly define patient risk profiles and disease characteristics that are most likely to benefit from telehealth. Empirical studies on how technology can help manage heart failure, COPD, and diabetes show that it has different effects on important outcomes such as hospital readmissions, avoidable emergency visits, and death rates. To help make better clinical and policy decisions about how to implement these technologies on a large scale, more research is needed to find out how effective they are based on age, tech literacy, mental health conditions that are present, and other factors that change the effects. Also, nurses play a big part in helping seniors get through difficult care transitions by educating patients, ensuring medications are taken correctly, and ensuring patients follow their post-discharge care plans. Looking at evidence on nursing-led telehealth patient engagement and education can help find high-impact connection points along the journeys of elderly patients to offer important personalised support and better self-management.

Since COVID-19 emergencies forced rapid scaling, the use of virtual care has grown significantly. To strategically equip overworked systems for the growing number of older people around the world, it is becoming increasingly important to find a balance between interventions that have been shown to work, using them ethically without any exceptions, and being good stewards of limited care resources. This systematic review combines evidence from randomised controlled trials examining remote chronic disease management programmes for older patients. It found interesting patterns in the types of interventions and how they were put into action linked to better or no clinical outcomes. The results will help nurses better use telehealth, set study priorities for future care for the elderly, and make policy changes to help deal with the growing public health problem of chronic diseases in the world’s ageing populations.

1.2 Research problem and significance

The challenges in using telehealth’s potential to help older people manage chronic conditions make this an increasingly important area of study. As age-related comorbidities like heart disease, diabetes, and respiratory sickness put more stress on healthcare systems that are already overworked, it is essential to find the right ways to help patients take charge of their care and coordinate their care through remote methods (Xiao and Han, 2022). However, clinical studies focusing on telehealth applications report mixed results, highlighting the complicated, situation-specific factors affecting outcomes. It is still important to be clear about the specific chronic conditions, patient risk profiles, ages, and technological literacy levels where virtual interventions consistently work or don’t work for a strategic application that balances ethical needs with good resource management.

This systematic study directly addresses the issue of inconsistent research results on the effects of telehealth, making it harder for widespread adoption based on good information. Putting together evidence on the patient, illness, and intervention factors that are linked to better or worse outcomes can give nurses useful information that can be used to guide future practice, study, and policy changes. As the world’s elderly population grows by millions over the next few decades, it will be important to control unnecessary hospital stays and help high-risk seniors stay independent through custom solutions. This will ensure long-term care delivery and better public health (Xiao and Han, 2022). To properly equip systems already under a lot of stress, it is important to know which parts and delivery methods of telehealth work best to ease the load.

The importance of the research is linked to the urgency of finding evidence-based paths to reconfigure care models for the growing burden of chronic disease in ageing countries such as the United Kingdom, where comorbidities are prevalent. The elderly account for up to 25% of total hospital bed capacity, predicting a 39% increase in patients over 65 by 2035 (Government Office for Science, 2016). The resulting pressures necessitate data-driven adoption of innovative modalities that have been shown to improve patient-centred quality of life and care coordination across settings. As important connections managing complicated transitions, nurses must stay current on the newest innovations in targeted telehealth optimisation while balancing the ethical challenges of equitable access. This assessment informs meaningful nurse-led innovation and health policy reforms that prioritise geriatric support through virtual methods by exposing particular areas for technical refinement and patient-centric personalisation.

1.3 Aim, Objectives, and Research Question

Research Question

What are the key factors influencing the effectiveness of telehealth interventions in managing chronic conditions in elderly patients, and how can the findings contribute to enhancing nursing practices, setting research priorities, and influencing policy changes?

Aim

This project aims to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the existing literature on telehealth interventions for treating chronic illnesses in elderly patients, to synthesise data to educate nursing practices, guide future research priorities, and impact policy changes. In particular, the study aims to achieve the following research objectives:

- To review and analyse existing literature on telehealth interventions for chronic disease management in elderly populations, considering factors such as age, comorbidities, technological literacy, and intervention types.

- To identify patterns and trends in the effectiveness of telehealth interventions in improving clinical outcomes, patient self-management, and care coordination for elderly individuals with chronic conditions.

- To provide evidence-based recommendations for nurses, policymakers, and researchers on the strategic implementation of telehealth in senior care, considering ethical considerations and resource management.

A comprehensive review will compile findings from randomised controlled trials assessing telehealth technologies for remote management of chronic cardiovascular, pulmonary, endocrine, and other noncommunicable diseases in patient populations over 60 years old to answer the study question. Conditions. A systematic literature evaluation will be used in this study, emphasising randomised controlled trials of telehealth therapies for older patients with chronic illnesses. To discover papers that match the inclusion criteria, the review will thoroughly search relevant databases such as PubMed, Cochrane Library, Sage journals, BMC journals, Frontiers, and others. Data extraction and synthesis will be carried out to investigate the patterns and factors contributing to the success or failure of telehealth interventions. The goal of this outcomes synthesis, combined with qualitative analysis of successful intervention features and implementation considerations, is to delineate evidence-based protocols guiding nursing practice to leverage telehealth tools to improve care coordination, self-management support, and quality of life for higher-risk elderly with complex comorbidities. The discussion will focus on converting findings into practical methods for optimised, ethical adoption tailored to the needs of elderly patients managing chronic conditions.

1.4 Definition of Key Terms

1.4.1 Telehealth

Telehealth means using communication tools to give medical care to people far away. Telehealth is now useful because of medical technologies, computer science, computing, and communication progress. In telehealth, blood pressure, heart rate, and other measures are often taken from a patient’s device and sent electronically to medical staff to monitor them from afar (NMC health, 2020). As smartphones and other smart personal devices become more common worldwide, even in rural, underserved areas, they are used increasingly to collect, share, and analyse health data (National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, 2020). Doctors and patients have had many virtual visits in the past few years. This has become particularly common since the COVID-19 pandemic started. Virtual medicine will likely stay a popular choice in healthcare as long as doctors, patients, and insurance companies are willing to use it.

1.4.2 Chronic Conditions

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), also called chronic diseases, last a long time and are caused by genetic, physiological, environmental, and behavioural factors (World Health Organization, 2023). Cardiovascular diseases (like heart attacks and strokes), cancers, chronic lung diseases (like asthma and COPD), arthritis and diabetes are the main types of NCD.

1.4.3 Elderly Patients

This study includes older adults who are 60 years old and above.

2.0 Methodology

2.1 Literature Review vs. Systematic Review

The types of methods used and the areas they are supposed to cover are very different between a literature review and a systematic review. The difference between a literature review and a systematic review comes back to the initial research question. (Robinson and Lowe, 2015) The systematic review is very specific and focused, but the standard literature review is much more general. Still, systematic reviews use a clear, organised, and reusable method to find, evaluate, and combine evidence that answers a specific research question.

Multiple benefits come from using the systematic review method. As a systematic review searches multiple sources using set criteria to find studies that meet certain criteria, it looks at a larger number of studies. It lowers the chance of selection bias that can happen with literature reviews. Additionally, systematic reviews include a quality assessment of the studies they include, which lets the validity and reliability of data be carefully evaluated (Robinson and Lowe, 2015). This in-depth analysis lets either a quantitative or qualitative synthesis come to a final decision. Unlike a normal literature study, the systematic approach reduces bias and increases objectivity at several stages. Therefore, systematic reviews provide stronger and more reliable evidence that can be used to shape policies, practice standards, and the direction of future research. Additionally, the systematic approach makes finding any remaining information gaps easier. Sticking to the framework for systematic reviews makes the results more reliable and useful for making decisions based on proof.

2.2 PICO/PEO Criteria

The Population, Exposure, and Outcome (PEO) criteria for this review are as follows:

- Population: Elderly individuals (65 years and older) diagnosed with one or more chronic conditions.

- Exposure: Telehealth interventions, including remote monitoring, evaluation, and/or rehabilitation.

- Outcome: Qualitative assessments of the impact of telehealth interventions on the management of chronic conditions, with a focus on patient experiences, perceptions, and overall satisfaction.

2.3 Literature Search Strategy

Multiple searches will be done in relevant databases, such as PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Google Scholar, Scopus, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, to find articles that meet the inclusion requirements. It will use keywords and controlled vocabulary to find information about telehealth, chronic conditions, older patients, and qualitative study methods. Across databases, search terms will be changed to match unique index terminologies, but the main ideas will stay the same. More accurate results will be obtained using Boolean operators and filters for qualitative studies, age groups, and release dates. Additional relevant citations will be found by hand-searching the reference lists of eligible papers.

The Boolean operators’ search string used was: (“telehealth” OR “telemedicine” OR “ehealth” OR “mhealth”) AND (“qualitative research” OR “qualitative stud*” OR “focus group*” OR “interview*”) AND (“elderly” OR “older adult*” OR “senior*” OR “geriatric”) AND (“chronic disease” OR “chronic condition*” OR “chronic illness*”).

2.4 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The studies must include original qualitative research published in peer-reviewed journals between 2018 and 2023 examining how telehealth treatments could help older patients (60 years and older) manage chronic diseases. Conditions like diabetes, high blood pressure, heart failure, chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD), arthritis, and chronic kidney disease are all of interest. Some examples of telehealth technologies are the phone, videoconferencing, remote monitoring devices, mHealth apps, and text message platforms that let care be given without physically visiting the patient. Accepted studies must report qualitative results gathered through interviews, focus groups, participant observations, or open-ended poll questions about stakeholders’ experiences with telehealth interventions. No articles will be accepted if they don’t focus on older people, talk about telehealth, or lack original qualitative research like reviews or opinion pieces.

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

| Qualitative research studies | Studies conducted outside 2018-2023 |

| Elderly population (60 years and older) | Studies not focusing on telehealth interventions |

| Exploration of subjective experiences | The study focuses on the population below 60 years old |

| Telehealth interventions | |

| Chronic conditions | |

Table: Inclusion and exclusion criteria

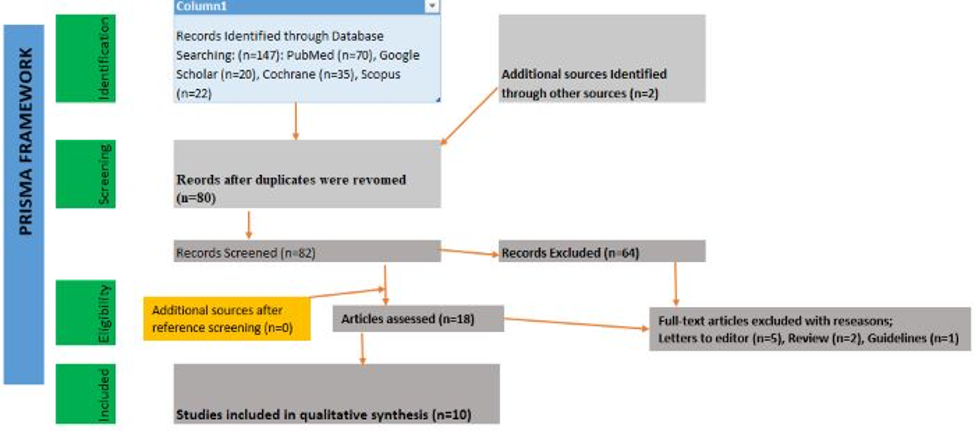

The search of the database found 147 first records. Title and summary screening got rid of 67 records after getting rid of duplicates. This left 82 articles checked for eligibility, and 18 remained. 10 studies were chosen for the qualitative synthesis after the qualifying criteria were applied during the full-text review. Below is a PRISMA flow map showing the steps to choose a study.

Figure 1: PRISMA Framework

The study participants conducted semi-structured interviews about their experiences with telehealth services for managing chronic diseases. Individuals in the group had a range of chronic conditions, telehealth methods, locations, and socioeconomic levels. Follow the review process’s instructions from the Cochrane Collaboration to reduce bias in choosing studies and getting data. Independently, two reviewers will check each record to see if it is eligible and use a piloted form to pull out study data and themes. Resolving any disagreements will involve talking about them. Study rigour will be judged using the consolidated standards for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) for a quality appraisal (de Jong et al., 2021). The data will be analysed using the thematic synthesis method, and themes from different studies will be grouped (Thomas and Harden, 2018). The protocol for this systematic review describes a thorough method for combining qualitative data to determine how older patients and providers feel about using telehealth to manage chronic diseases.

3.0 Literature Review

3.1 Effectiveness of telehealth interventions on clinical outcomes in elderly patients

Many studies have shown that telehealth treatments can help older people with long-term illnesses stay healthier. People with many chronic diseases can better care for themselves, keep an eye on their health, and benefit better from telehealth (Guo and Albright, 2018). For example, blood sugar and blood pressure were lower in older people with diabetes and heart disease. They found that telehealth made it easier for people to take their medicines as prescribed. It also improved their health-related quality of life, knowledge of health problems, and belief in their ability to handle them. Also, glycated haemoglobin, pain, signs of depression, and shortness of breath went down. According to Kirakalaprathapan and Oremus’ systematic review of 22 RCTs, hospitalisations linked to cardiovascular disease went down when telehealth was combined with remote monitoring technologies. Ruben et al. (2023) also did a systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 RCTs. They found that telehealth had significant clinical benefits on physical fitness (as measured by the six-minute walk test) and general health conditions in older patients with chronic pulmonary disease, asthma, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and fibromyalgia compared to usual care without face-to-face intervention during the study period.

Multiple randomised controlled trials and literature reviews showed mostly positive effects. However, a few other studies found mixed or limited effects of telehealth interventions on better clinical outcomes in older people. According to Jiang et al. (2022), a qualitative study found that problems with technology, hearing problems that made video visits hard, and being unable needing help to do physical exams in person are some of the things that make telehealth less useful. Using a systematic review, Mallow et al. (2021) found that telehealth interventions lasting less than 38 weeks had neutral or mixed clinical outcomes for people with chronic illness. This suggests that longer-term, sustained telehealth efforts are needed for consistently positive effects. Only 3 of the 22 RCTs that Kirakalaprathapan and Oremus (2022) looked at had a low risk of bias based on the Cochrane tool, which means that the quality of the studies should be carefully evaluated using risk of bias assessment.

Modality, length of intervention, integrated care delivery models, and tailored to individual needs are some of the most important factors that may affect how well telehealth treatments work to improve clinical outcomes in older people. Multiple physiological factors, such as heart rate, heart rhythms, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and symptoms, being monitored remotely works better than video visits or weight monitoring alone (Creber et al., 2023). Continuous, unified telehealth efforts that send data straight to a patient’s current medical team are more likely to succeed than short-term research studies that run parallel and don’t coordinate care. Tweaking telehealth to each patient’s level of technology knowledge, ability to access high-speed internet, digital literacy, disability, and personal tastes is also important for getting the most out of it (Kruse et al., 2020). So far, the evidence shows that telehealth has a lot of promise to help older patients get better care if used appropriately. However, more study is needed to find the best ways to intervene, how long to work with people, how to combine this with regular care, and how much customisation is needed to meet the needs and preferences of each user.

3.2 Role of telehealth in improving self-management in elderly patients

Telehealth tools like mHealth apps, videoconferencing, text messaging, and remote monitoring could help older people better manage their long-term illnesses. Many studies have shown that telehealth can help seniors with diabetes, COPD, and heart failure get better at self-care, self-monitoring, and overall health. In 2018, Guo and Albright looked at 31 RCTs with senior patients and found that telehealth helped them take their medications as recommended, changed how they behaved regarding their health and solved problems. Remote tracking helped heart failure patients take their medications as prescribed and live healthier lives, making self-management easier (Kirakalaprathapan and Oremus, 2022). Patients who used telehealth also had better control over their blood sugar, blood pressure, and other disease signs than people who did not use telehealth. However, some studies found that the good effects lasted less and less over time.

Seniors can use telehealth to take care of their physical needs and also meet their emotional needs. Surveys show that telehealth makes older people feel more independent, socially linked, and good about their quality of life (Şahin, Veizi, and Naharci, 2021). Video visits can bring seniors stuck at home with someone to talk to and help them feel less alone. Still, user-centred design is important because older patients say that not knowing how to use technology, system complexity, cost, and not being able to do much with passive monitoring are all things that make it hard for them to accept. These problems can be fixed with training, easy-to-use interfaces, useful data input, and working together with current care teams (Jiang et al., 2022). The study makes a strong case for telehealth to improve self-management in many areas. However, continuing to focus on accessibility and long-term engagement will make it most effective at giving older adults more power.

Targeted training will help make it easier for older people to use telehealth while addressing common problems like a need for digital literacy. Telehealth platform users over 65 should be taught how to use them so they can confidently and freely (Banbury et al., 2019). With hands-on help from therapists or coaches, you can learn the technical skills you need. Another way to build digital literacy is to train family caregivers as telehealth facilitators (Mallow et al., 2021). Persistent engagement depends on how easy it is to use, how useful it is, and how well it fits in with healthcare teams. To show worth, telehealth data must give actionable, personalised feedback. Reimbursement policies will also shape usage, though evidence suggests telehealth’s cost-effectiveness for chronic disease management versus usual care (Creber et al., 2023). In the end, better self-care through telehealth will come from technologies and services that are carefully thought out and fit the wants and lifestyles of older users.

3.3 Patient and provider perspectives on telehealth in elderly care

The qualitative study by Jiang et al. (2022), which used 52 interviews, gives us much information about how patients and providers feel about using online tools to help older people with COPD. Interviewing older people over 60 and their multidisciplinary care team members gave the analysis a lot of hope that telehealth would make it easier and more accessible for older patients to get health services and consultations. However, patients confronted many problems when independently using online platforms and new technologies. This shows that older users need more help with digital literacy and easier-to-use interfaces. While this was going on, many providers saw that telehealth could save a lot of time and money when caring for this group of people with chronic conditions. At the same time, they were worried that relying on children or other caregivers for hands-on technology help could lead to family coercion or compromise patients’ privacy and honesty when talking remotely.

Furthermore, Şahin, Yavuz, and Naharci’s (2021) systematic review of evidence from 22 published studies confirmed that patients generally had positive experiences with telemedicine, especially when they were older. Satisfaction measures consistently showed that older patients found virtual modalities easy to use, practical, and useful for meeting routine, non-urgent care needs, such as refilling their medications and following up with their specialists. Patients and providers were sceptical about telehealth’s full replacement potential. This is because it’s hard to do hands-on physical exams virtually and build the same close, trusting relationships between patients and doctors over time as regular in-person visits. Findings suggest that the best way to apply this for older people might be to use telemedicine as an extra tool to improve access and coordination while still allowing for necessary in-person consultations based on the severity of the condition and the way the care relationship works.

Also, in Banbury et al.’s (2019) educational intervention trial with older Australian cohorts, seniors felt much more socially connected and supported during videoconferencing sessions, as shown by poll results. Participants’ qualitative feedback also showed that they liked the group learning format and how it helped them learn how to better control their health by interacting virtually with other people who were going through the same problems. This pointed to important psychological and social benefits with carefully planned video services teaching seniors about health and diseases. But the study sample didn’t include people who weren’t good with technology. This means that the effects of engagement can not be applied to the lowest-functioning elderly, who are most likely to be left out and alone without planned accessibility measures and help to learn how to use virtual care tools.

3.4 Role of telehealth in improving access to care

Improved access to healthcare services across several dimensions is a significant benefit of telehealth for elderly individuals. According to Ahin, Yavuz, and Naharci’s (2021) systematic review, telehealth assists older adults in overcoming geographical barriers to care, such as transportation issues commonly encountered by seniors with functional impairments, as well as connecting those living in underserved rural areas lacking speciality providers to urban medical centres. Kruse et al. (2020) observed that telehealth video visits and remote monitoring functionalities boosted accessibility for older patients with limited mobility and chronic conditions by eliminating the need to visit facilities physically. Furthermore, well-integrated telehealth platforms can help senior patients have coordinated access to diversified multidisciplinary treatment by digitally linking them to their existing care team, which includes specialists, primary care clinicians, pharmacists, social workers, and care managers.

However, widespread institutional impediments prohibit many socioeconomically disadvantaged older people from having fair access to telehealth services. According to Masterson Creber et al.’s (2023) review, limitations such as a lack of dependable broadband internet access, limited digital literacy, and the inability to acquire video-capable devices can severely limit telehealth accessibility among minority and low-income older persons. Mallow et al. (2021) conducted a separate systematic review that emphasised how the ongoing lack of insurance coverage for telehealth services and digital divide difficulties along socioeconomic lines threaten to prolong health inequities despite the rise of virtual care choices. Thus, thoughtful program design features such as device/hotspot distribution and digital literacy education, in conjunction with advocacy efforts to expand insurance coverage, represent critical avenues for ensuring that telehealth improves, rather than exacerbates, healthcare access divides in the elderly population.

3.5 Ethical considerations with telehealth for elderly patients

Accessibility and ease are good things about telehealth for older patients, but privacy, security, and the complexity of virtual care relationships raise ethical questions. Jiang et al. (2022) interviewed older users and found that they needed help handling large amounts of online health data and ensuring it was reliable. They needed help to make good use of resources. Many sources are only sometimes reliable, so there is a chance of getting the wrong information. Elderly patients might not know how to tell if a health site is trustworthy or how to keep their credentials safe. Providers are morally obligated to help seniors use tools correctly and properly while ensuring they don’t get too much information. Regarding security, telehealth platforms must protect patient privacy with reasonable measures such as access controls, encryption, and consent processes. However, there is still a chance that someone could access the data without permission while it is being sent or stored (Kruse et al., 2020). Breaches can make private health information public, which is disrespectful. Vendors should use best practices for user authentication, safe networks, and timely software updates to find and fix vulnerabilities before they happen. Patients should also be aware of the risks and safety steps in place.

It’s also harder to make therapeutic alliances and human ties in a virtual setting than in a real one. Providers may find it easier to make accurate assessments or show empathy with physical and visible cues that give context. On the other hand, seniors may feel alone or distrustful of technology (Banbury et al., 2019). Less social interaction affects the level of care. Some ethical problems with virtual-only care can be solved by teaching clinicians a “website manner” and keeping some face-to-face visits in a blended care approach. Even though telehealth makes it easier for people to get medical care, some older adults have different digital literacy or broadband connectivity levels than others. This raises worries about fairness if the rise in adoption leads to less traditional medical infrastructure (Ruth Masterson Creber et al., 202з). Policymakers and payers should ensure that telehealth adds to fair access for everyone, not take it away. Putting money into giving underserved areas access and skill-building can help stop the digital divide.

A thoughtful implementation of telehealth needs stakeholders to be aware of, open about, and involved with known ethical problems. As Banbury et al. (2019) outline, providers should be honest with customers about the pros and cons of their services and the safety measures they use to build trust. Informed agreement is possible when people have honest conversations about what they expect. Involving elderly users and patient supporters in the design process during development can help find problems and make interfaces more suitable for these groups (Jiang et al., 2022). Health systems need to monitor digital differences during rollout and spend money on training and support to keep care levels from being unfairly divided. To use telehealth correctly, it should be patient-centred, personalised, and mindful of the emotional parts of care. Thoughtful preparation and testing can make telehealth a risk-free method for helping older people. To be ethical, they must stay aware as technologies and patients’ wants alter.

3.6 Strategies for effective implementation of telehealth in geriatric care

To effectively utilise the telehealth systems to help older patients, groups must work together to get more of them to use them and make them easier for them to get to while keeping in mind that older people have different needs and limitations than younger people. There are a lot of seniors who use computers, smartphones, and other tech every day (Şahin, Yavuz and Naharci, 2021). However, some of these seniors still have physical or mental problems that make it hard for them to use virtual care platforms without help. A larger group of older people can fully participate by making implementation plans that include specialised accessibility equipment as needed, making telehealth interfaces easier for older end-users by including them in the design process and giving family members or caregivers specialised training. Detailed questionnaires showing specific problems related to getting older in areas like vision or hearing can help service providers focus on specific help solutions, like video platforms with bigger screens or basic voice communication tools that work better with declining abilities. Noteworthy, preliminary research projects have discovered that giving telehealth tablets to groups of elderly patients already loaded with senior-friendly apps and features greatly increased their engagement and continued use because they were so easy to use. This model needs more research before it can be used on a larger scale.

Also, developing new, flexible hybrid consultation methods can help older people get around access problems while keeping important in-person parts that this group needs. For instance, visiting nurse practitioners who are part of care teams might make telehealth appointments easier by helping with setting up home devices and fixing technical issues. They could also act as on-site guides for important parts of the physical exam that can be guided virtually by specialists who are far away (Şahin, Veizi and Naharci, 2021). This kind of multidisciplinary collaboration, providing care through a balanced integration of virtual and face-to-face pathways tailored to each case, could greatly improve clinical outcomes and care coordination for medically complex older patients until they are more comfortable and skilled with using technology independently. Also, social workers could make regular home visits to older people’s homes to teach them basic digital literacy skills through hands-on tutorials focusing on skill-building so that they can eventually use telehealth platforms independently. The outreach programs are also helpful in educating older adults with telehealth technology.

However, even the most well-designed and user-friendly telehealth platforms may only achieve widespread acceptance with participant buy-in and fostered technology self-efficacy. Thus, when introducing telehealth systems to elderly patients, it is critical to prioritise cultural sensitivity and trusted relationship building with content and messaging that resonates with lived experiences and emphasises preserved independence and family connections over isolation or diminished capacities (Şahin, Veizi and Naharci, 2021). Using varied focus groups to vet instructional materials and co-design platform features with target constituents can increase buy-in and interest while calibrating to acceptable health literacy levels. Post-implementation user feedback surveys also provide information to inform continuous modifications to address changing user preferences and difficulties. Finally, sustained utilisation heavily depends on whether telehealth programs are agile and sensitive to exposed challenges with plenty of patience and understanding.

Finally, the pandemic sped up the adoption of telehealth services across all areas of healthcare. However, it is still important to keep up with training and support systems specifically aimed at getting the oldest population to use them even after the crisis. This will ensure their long-term viability and central position in care delivery (Haimi and Gesser-Edelsburg, 2022). Policies about telehealth should pay for specialised training for patients and providers, make assessment tools that are easy to use and show platform problems through anonymised data, and include ways for patients who don’t have family caregivers to get help from specialists like visiting health aides or social workers. Allowing elderly users to tell problems they’re having with quick fixes easily also promotes accessibility and lets them know that their struggles are being heard. Many people can get more convenience and care through virtual care. Still, mobility and care coordination improvements are only guaranteed if this new area is walked carefully and with compassion, especially for older people, who may benefit the most in terms of quality of life if adoption is facilitated with care.

4.0 Results and Findings

The systematic study aimed to find out how well telehealth interventions help older people with chronic conditions. The studies that were looked at showed a few main themes that helped to understand what makes telehealth work, how it affects clinical outcomes and self-management, the patient and provider perspectives, access to care, ethical issues, and strategies for implementation.

Factors Influencing Telehealth Effectiveness

Much research has shown that different factors can affect the effectiveness of telehealth treatments. Some of these are the type of telehealth used, the time of the intervention, models for delivering integrated care and making interventions fit the needs of each person. For older people with long-term conditions, continuous, unified efforts with online monitoring of physiological factors like heart rate and blood pressure were more effective than video visits alone. The success of telehealth also depended on how well interventions were tailored to the technological knowledge, internet access, and personal tastes of older patients.

4.2 Impact on Clinical Outcomes and Self-Management

These interventions positively affected clinical outcomes in older patients with chronic conditions. Studies have shown that older people with chronic diseases can improve their self-care skills, self-monitoring habits, and clinical outcomes. For example, older people with diabetes and heart failure who used telehealth had lower blood pressure and blood sugar levels. Long-term involvement and constant monitoring are necessary for long-lasting positive effects on clinical outcomes for older patients with chronic conditions.

4.3 Patient and Provider Perspectives

The qualitative studies provided useful information about how both older adults and providers of older adults felt about telehealth interventions. Most older adults who used telehealth had good experiences. They found it easy to use and useful for their regular care needs. However, problems were found with older people, such as their need for digital skills and help using technology. Providers knew that it could save them time and money. Still, they were worried about family members being able to force their children to do things, patients’ privacy being invaded, and the difficulties of doing physical exams online on elderly patients.

4.4 Access to Care

Telehealth has made medical care much easier for older people with long-term illnesses. One important benefit was getting around geographical barriers, especially for older adults who live in rural or underserved places. But problems like the digital gap, not having reliable broadband internet access, and not knowing how to use technology well were named as issues that could make it harder for some people to get the healthcare they need, especially older people from low-income families managing chronic illnesses.

4.5 Ethical Considerations

Concerns about ethics included privacy, safety, and the difficulty of virtual care ties for older patients. Patients over 65 had trouble managing large amounts of online health data, and worries were made about data security and breaches. Because there were no physical cues in virtual settings, it was hard for providers to make correct assessments and empathise with elderly patients. For older people to use telehealth ethically, it was decided that protecting patient privacy through encryption and access controls, teaching digital skills, and encouraging human connections in virtual care were all important.

4.6 Strategies for Effective Implementation

Tips for successful implementation of telehealth in geriatric care stressed the need for specialised training, adaptable hybrid conversation methods, and ongoing support specifically designed for older users. Specialised accessibility equipment, letting older people help with the planning process, and training family members or caregivers were important ways to get more older people to use and access technology. Cultural sensitivity, building relationships, and getting feedback from users regularly were stressed as ways to help older people with chronic diseases who use telehealth feel more confident in their technology skills and keep using it.

5.0 Recommendations and Implications for Nursing

5.1 Summary of Findings

This systematic review looked at all the research that has already been done on using telemedicine to help older people with chronic diseases. The purpose was to combine data to improve nursing practices, plan future studies, and change policies related to the strategic use of telehealth in senior care.

An analysis of 10 qualitative studies revealed several important factors that affect how well telehealth works for older people with long-term illnesses. Findings showed that outcomes were affected by the type of telehealth used, the time of the intervention, the models of care integration, and how each person was treated. Multiple physiological parameters could be monitored remotely over a long period, and coordinated efforts were more successful than single video visits or basic weight tracking. Experts stressed the importance of tailoring telehealth solutions to each patient’s level of technology knowledge, access issues, and personal tastes.

Telehealth interventions mostly had good effects on clinical outcomes, such as lowering blood sugar and blood pressure in older people with chronic heart and endocrine diseases. Furthermore, telehealth enhances understanding, self-care skills, and self-monitoring (De Groot et al., 2021). A common problem, though, was keeping patients interested for long amounts of time. In qualitative research, patients mostly had good experiences with telehealth, praising how convenient and useful it was. Others, though, needed help with technology. It saved providers time and money, but they were worried about privacy issues, family coercion, and doing physical exams from afar.

Significantly better accessibility overcoming mobility and geographical obstacles, was identified as one of the main possible benefits of telehealth for elderly patients. Barriers to care access could worsen if people need access to broadband internet, gadgets, or the knowledge to use technology (Gajarawala and Pelkowski, 2021) properly. Additional ethical concerns that needed to be protected included privacy and security risks that came with having a lot of patient health data on virtual platforms. Thoughtful implementation efforts, such as user-centred design, hybrid consultation models, and specialised training, were stressed to get benefits while lowering risks.

5.2 Implications for Nursing Practice

The results have several important implications for nurses caring for older people and handling chronic diseases. First, nurses should push for patient-centred telehealth policies and care models tailored to older people’s specific needs and challenges, such as their lack of technological literacy (Wong et al., 2022). To promote fair access, people must ask the government and health systems to support digital literacy programs, subsidised devices and internet, and telehealth insurance for underprivileged groups (Campanozzi et al., 2023). In their hospitals, nurses can lead the way in making personalised telehealth programs for older patients that include I.T. help and hands-on training from facilitators from different fields.

Second, nurses can improve older patients’ health outcomes and self-management skills by using telehealth to provide individualised teaching, skill development, and ongoing remote monitoring (Ghoulami-Shilsari and Bandboni, 2019). Moving from random video calls to integrated care plans that involve patients with easy-to-use devices and useful physiological data feedback is a big change from reactive to preventative care. Also, nurses should regularly check in with telehealth users to see how their experiences and needs are changing (Farokhzadian et al., 2020). They can do this through open contact and surveys to find problems right away and make improvements in a way that puts the patient first.

Third, nurses need to be the ones to deal with the ethical problems that come up with caring for older people online. They can do this by proactively pushing for privacy laws and policies that are kind to people (Booth et al., 2021). They can work with I.T. experts to establish strong data security measures and simplify the informed consent process. Holistic telehealth nursing lets nurses keep some in-person meetings if the patient wants them and the nurse thinks it’s necessary (Solimini et al., 2021). So, they can find a good mix between building relationships and coordinating care well. Even though virtual care is growing, it’s important to help people feel better and build trust.

5.3 Recommendations

5.3.1 Nursing Practice

There needs to be specialised implementation programs for seniors that include hands-on help in making platforms and continued training that breaks down barriers to accessibility with empathy and patience (Lee et al., 2022). Keeping up with preventative care and self-management tools with regular two-way data shows how telehealth can improve the health of senior communities.

Nurses must Support the promise of telehealth for older people. This requires progress in making access fair through patient-centred infrastructure, subsidies, and digital literacy programs for disadvantaged groups falling behind the digital divide because policymakers need to plan more (Amjad, Kordel and Fernandes, 2023).

Strong data protection and clear, easy-to-understand consent processes that explain risks, emphasise relationships over transactions, and raise people’s dignity through consistent emotional support and compassionate communication are needed for telehealth to be used ethically (Mittelstadt, 2017).

5.3.2 For Health Policy

Policies should be implemented to improve insurance coverage and payment options for home health and telehealth services (St John, 2022). Broader coverage would make it easier for low-income seniors who cannot afford their current insurance to get and use telehealth care.

For older people with low incomes, health policymakers should pay for complete digital literacy programs and free or cheap internet access and gadgets (Williams and Shang, 2023). These efforts would help fix the problem of systematic differences in the uptake of telehealth among seniors who can’t buy or use technology on their own.

Health policy should set up standardised outcome measures for telehealth services to compare them and find the best practices (Haleem et al., 2021). A thorough study of the best telehealth methods and implementation methods would be possible by collecting data using standard measures.

Health policies must be set up to keep private health information safe and spell out the best ways to protect privacy and security on telehealth platforms (Houser, Flite and Foster, 2023). These rules will set up a framework for protecting patient privacy and lowering the risks that come with personal medical information that isn’t encrypted on virtual care technology.

5.3.3 Future Research

In the future, researchers should focus on large-scale randomised controlled trials that directly compare different telehealth methods and implementation techniques in groups of older adults who are chronically ill. These studies are necessary to find the best technologies and ways for people to accept them so that they work best in the clinic and don’t cost too much. More study is needed to create and test digital literacy learning models and telehealth training programs specifically designed to meet the needs of older users (Haleem et al., 2021). Longitudinal studies examining how long telehealth treatments last and how they affect self-management skills and healthcare use over the years are also important to understand the long-term effects. More research using various methods to show how telehealth impacts therapeutic relationships, care coordination, and patient experiences from the points of view of different older people and healthcare providers would help us learn a lot about humanistic results (Giansanti, 2023). Lastly, thorough cost-benefit studies are needed to figure out how much money needs to be spent upfront on telehealth for a lot of older people to use it, compared to the money that could be saved on healthcare over time and more work getting done under different payment models (OECD, 2023). More studies in these areas in the future will help make evidence-based protocols that will be used to guide policy and implementation efforts that aim to safely increase the use of telehealth in caring for older people.

5.4 Limitations of the Study

Based on the search approach and the availability of existing literature, this systematic review has several limitations. The search was limited to English-language articles published between 2018 and 2023, ruling out potentially relevant older data (Rethlefsen et al., 2021). Extending the search dates and languages may yield further insights from various cultural situations. Furthermore, the included research was all qualitative, with small sample numbers. Larger-scale randomised controlled trials evaluating clinical and utilisation outcomes would be added to the database. Although having two independent reviewers helps decrease this risk, researcher bias could have been introduced during study screening and data extraction (Grames et al., 2019). Finally, the qualitative synthesis brought together perspectives from different chronic conditions, which misses disease-specific nuances in telehealth applications. Future assessments could concentrate on a single condition for more in-depth study.

The review’s principal weakness is the need for more quantitative data on the effects of telehealth interventions on measurable outcomes such as hospitalisations, emergency visits, healthcare expenses, and mortality (Xiao and Watson, 2019). Although the research is primarily qualitative, it gives rich contextual insights but lacks definitive clinical evidence. Direct comparisons and meta-analyses are problematic because of the significant variety in telehealth modes, study protocols, contexts, and outcome measurements. Additional large-scale pragmatic trials with consistent reporting of clinical and utilisation endpoints are required to determine the size of the benefits. Data on cost-effectiveness needs to be included. Finally, the research focused on community-dwelling older people, so the findings may not apply to telehealth applications in long-term care institutions. Significant knowledge gaps exist regarding optimum chronic illness management strategies across the continuum of senior care settings.

6.0 Conclusion

This systematic study aimed to identify the major factors impacting the success of telehealth treatments in managing chronic diseases in older people. A review of ten qualitative research found that telemedicine can enhance clinical outcomes such as blood pressure and blood sugar control in older persons with chronic conditions. The modalities, integrated care models, ongoing engagement, and adapting to individual requirements and tech literacy, on the other hand, determine effectiveness. Telehealth improved access and coordination for patients and providers, but older persons required additional training and assistance. While telemedicine improves accessibility, the digital gap threatens to widen unless legislative efforts to expand digital knowledge and access are made. Privacy, security, and virtual therapeutic connections are all ethical concerns that must be addressed. Adoption and satisfaction require careful implementation, including senior-focused design, hybrid models, and ongoing training. Telehealth can potentially improve chronic illness management in the elderly, but it requires planning and patient-centred implementation.

This review answers the study question about what makes telehealth work or not work for older people. The review found that the type of technology used, the length of the intervention, the integration of care, and the personalisation are the most important factors that affect results. By constantly sharing data with providers, remote tracking makes preventative care possible. Continuous, well-planned participation has a bigger effect than random use. To get around tech problems that come with ageing, platforms must be user-friendly for seniors and come with hands-on training. Self-efficacy and clinical indicators improve when telehealth is tailored to the person’s needs. On the other hand, one-size-fits-all solutions could make differences worse and turn people off. How well telehealth is used for different groups of older people will determine its impact. There are still big gaps in our knowledge because there have yet to be many clinical trials, but qualitative data can help us start making decisions about practice and policy.

One of the most significant recommendations is to start specialised training programs to help older people use technology better and learn how to use it properly by being sensitive to their needs and those of others. To stop telehealth from worsening healthcare disparities, it is also important to have programs that make devices and internet connections more affordable for struggling older people. For nursing practice, patient-centred coordination, self-management resources, ethical protections, and keeping human relationships must stay at the centre of nursing practice. To allow access while stopping coercion and data breaches, policymakers must add more scope, quality indicators, and privacy rules. Researchers should do large-scale controlled studies that compare different methods and strategies for implementing them, focusing on clinical utilisation, patient-reported, and cost results. Examining the long-term effects on self-efficacy and integrated care is also important.

There were some limitations with this study that could have changed the results. It was hard to decide how telehealth affects older patients because the included qualitative studies had small sample numbers, looked at a wide range of conditions, and needed clinical outcome data. The search was limited to studies from 2018 to 2023, so it’s possible that important data should have been included. There was a chance of researcher bias during screening and data extraction, but the work of two separate reviewers lessened this risk. This review has many good things, such as its organised approach that follows PRISMA standards, its thorough search of many databases, and its use of a proven quality assessment tool. The theme synthesis sheds light on useful information about patients and providers that can be used in moral and caring ways. The main goal of this project was to gather data to help nursing practice, and policy make better use of telehealth for older people with chronic diseases. This was done through a strict, repeatable method.

There is still a need for more large-scale clinical studies that directly compare the effects of different telehealth modalities, durations, and execution models on hospitalisations, costs, deaths, emergency visits, and patient-reported metrics. Representative groups of older people should be used in studies, and the long-term effects on combined care and self-efficacy should be examined. To help shape coverage and practice policies, it’s also important to do cost-benefit analyses and develop standardised quality measures. To help make sense of the details, strong sampling methods and qualitative studies on the experiences of both patients and providers would be a good addition to clinical data. It would give us useful comparison data to see how they can be used for certain conditions and in different care settings. Collaborations between nursing schools, government health agencies, telehealth vendors, and community groups can help get research findings quickly turned into useful programs and policies that let older people age and deal with chronic illnesses on their terms, using telehealth as a tool to help them instead of something that gets in the way. If used strategically and based on new data, virtual care delivery could be a big part of helping the ageing population get high-quality, coordinated care while still living independently.

Reference List

Amjad, A., Kordel, P. and Fernandes, G. (2023). A Review on Innovation in the Healthcare Sector (Telehealth) through Artificial Intelligence. Sustainability, [online] 15(8), p.6655. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086655.

Anon, (2020). Telehealth – NMC Health. [online] Available at: https://www.mynmchealth.org/services/telemedicine/#:~:text=The%20benefits%20of%20telemedicine [Accessed 24 Dec. 2023].

Banbury, A., Nancarrow, S., Dart, J., Gray, L., Dodson, S., Osborne, R. and Parkinson, L. (2019). Adding value to remote monitoring: Co-design of a health literacy intervention for older people with chronic disease delivered by telehealth – The telehealth literacy project. Patient Education and Counseling, 103(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.10.005.

Booth, R.G., Strudwick, G., McBride, S., O’Connor, S. and Solano López, A.L. (2021). How the nursing profession should adapt for a digital future. BMJ, [online] 373(1190). Doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1190.

Campanozzi, L.L., Gibelli, F., Bailo, P., Nittari, G., Sirignano, A. and Ricci, G. (2023). The role of digital literacy in achieving health equity in the third-millennium society: A literature review. Frontiers in Public Health, 11. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1109323.

De Groot, J., Wu, D., Flynn, D., Robertson, D., Grant, G. and Sun, J. (2021). Efficacy of telemedicine on glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. World Journal of Diabetes, 12(2), pp.170–197. doi https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v12.i2.170.

de Jong, Y., van der Willik, E.M., Milders, J., Voorend, C.G.N., Morton, R.L., Dekker, F.W., Meuleman, Y. and van Diepen, M. (2021). A meta-review demonstrates improved reporting quality of qualitative reviews following the publication of COREQ- and ENTREQ-checklists, regardless of modest uptake. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 21(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-021-01363-1.

De Simone, S., Franco, M., Servillo, G. and Vargas, M. (2022). Implementations and strategies of telehealth during COVID-19 outbreak: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08235-4.

Farokhzadian, J., Khajouei, R., Hasman, A. and Ahmadian, L. (2020). Nurses’ experiences and viewpoints about the benefits of adopting information technology in health care: a qualitative study in Iran. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, [online] 20(1), pp.1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-020-01260-5.

Gajarawala, S. and Pelkowski, J. (2021). Telehealth Benefits and Barriers. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, [online] 17(2), pp.218–221. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7577680/.

Ghoulami-Shilsari, F. and Esmaeilpour Bandboni, M. (2019). Tele-Nursing in Chronic Disease Care: A Systematic Review. Jundishapur Journal of Chronic Disease Care, In Press(In Press). Doi:https://doi.org/10.5812/jjcdc.84379.

Giansanti, D. (2023). Ten Years of TeleHealth and Digital Healthcare: Where Are We? Healthcare, 11(6), p.875. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11060875.

Government Office for Science (2016). Future of an Ageing Population. [online] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5d273adce5274a5862768ff9/future-of-an-ageing-population.pdf.

Grames, E.M., Stillman, A.N., Tingley, M.W. and Elphick, C.S. (2019). An Automated Approach to Identifying Search Terms for Systematic Reviews Using Keyword Co‐occurrence Networks. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, [online] 10(10), pp.1645–1654. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210x.13268.

Guo, Y. and Albright, D. (2018). The effectiveness of telehealth on self-management for older adults with a chronic condition: A comprehensive narrative review of the literature. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 24(6), pp.392–403. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633×17706285.

Haimi, M. and Gesser-Edelsburg, A. (2022). Application and implementation of telehealth services designed for the elderly population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Health Informatics Journal, 28(1), p.146045822210755. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/14604582221075561.

Haleem, A., Javaid, M., Singh, R.P. and Suman, R. (2021). Telemedicine for healthcare: Capabilities, features, barriers, and applications. Sensors International, 2(2). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sintl.2021.100117.

Houser, S.H., Flite, C.A. and Foster, S.L. (2023). Privacy and Security Risk Factors Related to Telehealth Services – A Systematic Review. Perspectives in Health Information Management, [online] 20(1). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9860467/.

Jiang, Y., Sun, P., Chen, Z., Guo, J., Wang, S., Liu, F. and Li, J. (2022). Patients’ and healthcare providers’ perceptions and experiences of telehealth use and online health information use in chronic disease management for older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02702-z.

Kirakalaprathapan, A. and Oremus, M. (2022). Efficacy of telehealth in integrated chronic disease management for older, multimorbid adults with heart failure: A systematic review. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 162, p.104756. doi https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2022.104756.

Kruse, C., Fohn, J., Wilson, N., Nunez_Patlin, E., Zipp, S. and Mileski, M. (2020). Barriers to Utilizing and Medical Outcomes Commensurate with the Use of Telehealth Among Older Adults: A Systematic Review (Preprint). JMIR Medical Informatics, 8(8). doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/20359.

Lee, A.Y.L., Wong, A.K.C., Hung, T.T.M., Yan, J. and Yang, S. (2022). Nurse-led Telehealth Intervention for Rehabilitation (Telerehabilitation) Among Community-Dwelling Patients With Chronic Diseases: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(11), p.e40364. Doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/40364.

Mallow, J., Davis, S.M., Herczyk, J., Pauly, N., Klos, B., Jones, A., Jaynes, M. and Theeke, L. (2021). Dose of Telehealth to Improve Community-Based Care for Adults Living with Multiple Chronic Conditions: A Systematic Review. E-Health Telecommunication Systems and Networks, 10(01), pp.20–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.4236/etsn.2021.101002.

Mittelstadt, B. (2017). Ethics of the health-related Internet of things: a narrative review. Ethics and Information Technology, 19(3), pp.157–175. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-017-9426-4.

National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (2020). Telehealth. [online] www.nibib.nih.gov. Available at: https://www.nibib.nih.gov/science-education/science-topics/telehealth.

OECD (2023). The future of telemedicine after COVID-19. [online] OECD. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-future-of-telemedicine-after-covid-19-d46e9a02/.

Rethlefsen, M.L., Kirtley, S., Waffenschmidt, S., Ayala, A.P., Moher, D., Page, M.J. and Koffel, J.B. (2021). PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Systematic Reviews, [online] 10(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z.

Robinson, P. and Lowe, J. (2015). Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39(2), pp.103–103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12393.

Ruben, D., Vieira, I., Denise Hollanda Iunes and Leonardo César Carvalho (2023). Analysis of the effectiveness of remote intervention of patients affected by chronic diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Medicine Access, 7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/27550834231197316.

Ruth Masterson Creber, Dodson, J.A., Bidwell, J.T., Breathett, K., Lyles, C.R., Still, C.H., Yu, J., Yancy, C.W. and Spyros Kitsiou (2023). Telehealth and Health Equity in Older Adults With Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation-cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1161/hcq.0000000000000123.

Şahin, E., Yavuz Veizi, B.G. and Naharci, M.I. (2021). Telemedicine interventions for older adults: A systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, p.1357633X2110583. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633×211058340.

Solimini, R., Busardò, F.P., Gibelli, F., Sirignano, A. and Ricci, G. (2021). Ethical and Legal Challenges of Telemedicine in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Medicina, [online] 57(12), p.1314. Doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57121314.

St, C. and John (2022). Telehealth and the Medicare Population: Building a Foundation for the Virtual Health Care Revolution. [online] Available at: https://medicareadvocacy.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Telehealth-Report_CMA_final.pdf.

The Kings Fund (2022). Long-term conditions and multi-morbidity. [online] The King’s Fund. Available at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/time-think-differently/trends-disease-and-disability-long-term-conditions-multi-morbidity.

Thomas, J. and Harden, A. (2018). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, [online] 8(1), pp.1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

Williams, C. and Shang, D. (2023). Telehealth Usage Among Low-Income Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Retrospective Observational Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, [online] 25, p.e43604. Doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/43604.

Wong, A.K.C., Bayuo, J., Wong, F.K.Y., Yuen, W.S., Lee, A.Y.L., Chang, P.K. and Lai, J.T.C. (2022). Effects of a Nurse-Led Telehealth Self-care Promotion Program on the Quality of Life of Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, [online] 24(3), p.e31912. Doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/31912.

World Health Organization (2023). Noncommunicable Diseases. [online] World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

Xiao, Y. and Watson, M. (2019). Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 39(1), pp.93–112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X17723971.

Xiao, Z. and Han, X. (2022). Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Telehealth Chronic Disease Management System: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (Preprint). Journal of Medical Internet Research. Doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/44256.

write

write