Background: Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory colon disease characterized by relapsing flares and remission episodes. However, the optimal steroid tapering strategy in patients hospitalized for acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC) remains relatively unknown. We aim to examine the clinical outcomes in patients hospitalized for ASUC concerning variable prednisone taper regimens upon discharge.

Methods: We retrospectively reviewed all adult patients admitted to our facility with ASCU between 2000-2022. Patients were divided into two groups based on the duration of steroid taper on discharge (< 6 weeks and > six weeks). Patients who had colectomy at index admission were excluded from the analysis. The primary outcome was rehospitalization for ASUC within six months of index admission. Secondary outcomes included the need for colectomy, worsening endoscopic disease extent and severity during the follow-up period (6 months), and a composite outcome as a surrogate of worsening disease (defined as a combination of all products above). Two-sample t-tests and Pearson’s chi-square tests were used to compare the means of continuous and categorical variables, respectively. It involved performed multivariate logistic regression analysis to identify independent predictors for rehospitalization with ASUC.

Results: A total of 215 patients (short steroid taper = 91 and long steroid taper = 124) were analyzed. A higher number of patients in the long steroid taper group had a longer disease duration since diagnosis and moderate-severe endoscopic disease activity. (63.8 months vs. 25.6 months, p <0.0001, 46.8% vs. 23.1%, p = ≤ 0.05, respectively). Both groups had similar disease extent, prior biologic therapy, and the need for inpatient recuse therapy. At the 6-month follow-up, rates of rehospitalization with a flare of UC were comparable between the two groups. (68.3% vs. 68.5%, p = 0.723).On univariate and multivariate logistic regression, escalation of steroid dose within four weeks of discharge (aOR 6.09, 95% CI, 1.82 – 20.3, p=0.003) was noted to be the only independent predictor for rehospitalization with ASUC.

Conclusion: This is the first study comparing clinical outcomes between post-discharge steroid tapering regimens in hospitalized patients for ASUC. Both examined steroid taper regimens upon discharge showed comparable clinical results. Hence, we suggest a short steroid taper as a standard post-hospitalization strategy in patients following ASUC encounters. It is likely to enhance patient tolerability and reduce steroid-related adverse effects without adversely affecting outcomes.

|

Table 1. Baseline demographics of UC patients treated with short and long steroid taper regimens |

|||

| Factor | Short steroid taper

(n = 91 ) |

Long steroid taper

(n = 124 ) |

P value |

| Age (mean – years. ) | 43.7 ± 18.6 | 39.9 ± 15.9 | 0.108 |

| Age at UC diagnosis (mean – years.) | 32.5 ± 17.3 | 31.0 ± 15.7 | 0.509 |

| Male (n%) | 33 (36.3%) | 54 (43.5%) | 0.282 |

| Race (n%) | |||

| Caucasian | 55 (60.4%) | 70 (56.5%) | 0.083 |

| African American | 5 (5.5%) | 13 (10.5%) | 0.237 |

| Hispanic | 2 (2.2%) | 8 (6.5%) | 0.169 |

| Smoking (n%) | 0.066 | ||

| Never | 33 (36.3%) | 34 (27.4%) | |

| Current | 54 (59.3%) | 89 (71.8%) | |

| Past | 4 (4.4%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| Disease duration (months) | 25.6 ± 9.59 | 63.8 ± 22.9 | 0.0000 |

| LOS ( days) | 4.34 ± 3.59 | 5.35 ± 4.73 | 0.090 |

| Steroid use in the past six months | 53 (58.2%) | 76 (61.3%) | 0.652 |

| The extent of disease at index hospitalization | 32 | 61 | 0.159 |

| Proctosigmoiditis | 6 (6.6%) | 12 (9.7%) | |

| Left-sided colitis | 9 (9.9%) | 23 (18.5%) | |

| Extensive colitis | 13 (14.35%) | 25 (20.2%) | |

| Prior Biologic Therapy (n%) | 35 (38.5%) | 59 (47.6%) | 0.206 |

| Prior Anti-TNF therapy (n%) | 34 (37.4%) | 51 (41.1%) | 0.160 |

| Type of Biologic agent | |||

| Infliximab | 27 (29.7%) | 36 (29.0%) | 0.162 |

| Adalimumab | 15 (16.5%) | 22 (17.7%) | 0.645 |

| Vedolizumab | 11 (12.1%) | 25 (20.2%) | 0.275 |

| Ustekinumab | 1 (1.1%) | 4 (3.2%) | 0.404 |

| Golimumab | 1 (1.1%) | 2 (1.6%) | 0.876 |

| Certolizumab | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0.435 |

| No. of biologics used in the past (n%) | 0.971 | ||

| One agent | 20 (21.9%) | 33 (26.6%) | |

| ≥ 2 agents | 16 (17.6%) | 26 (21.0%) | |

| Endoscopic disease activity at Index hospitalization (n%) | 31 | 61 | 0.004 |

| Mayo 2 | 11 (12.1%) | 24 (19.4%) | |

| Mayo 3 | 10 (11.0%) | 34 (27.4%) | |

| CRP within one week of discharge (mean – mg/dl.) | 10.8 ± 24.5 | 11.5 ± 30.8 | 0.868 |

| Fecal calprotectin within one week of discharge (mean – ug./g.) | 2993.3 ± 2075.3 | 2721.2 ± 1748.3 | 0.6647 |

| Inpatient rescue therapy (%) | 11 (12.1%) | 21 (16.9%) | 0.324 |

| In-hospital colectomy (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | – |

| Table 2. Outcomes in UC patients treated with short and long steroid taper regimens | |||

| Factor | Short steroid taper

(n = 91 ) |

Long steroid taper

(n = 124 ) |

P value |

| Follow-up within four weeks of discharge (%) | 59(64.8%) | 96 (77.4%) | 0.042 |

| Time to biologic initiation (days) | 130.8 ± 405.3 | 91.3 ± 436.8 | 0.639 |

| Biologic initiation beyond six weeks (%) | 22(24.1%) | 50 (40.3%) | 0.126 |

| CRP within six mths from index admission | 4.28 ± 6.73 | 2.95 ± 4.01 | 0.145 |

| FC within six mths from index admission | 2029.9 ± 1530.7 | 1609.2 ± 1594.1 | 0.499 |

| Steroid dose escalation within four weeks of discharge (%) | 25 (27.4%) | 15 (12.1%) | 0.004 |

| Readmission within six months (%) | 41 (45.5%) | 54 (43.5%) | 0.826 |

| Reason for readmission (%) | 43 | 54 | |

| The flare of Ulcerative colitis | 28 (68.3%) | 37 (68.5%) | 0.723 |

| Sepsis | 4 (4.4%) | 3 (3.2%) | 0.479 |

| Surgery | 2 (2.2%) | 6 (6.5%) | 0.251 |

| C. Diff colitis | 1 (2.4%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0.187 |

| Others | 8 (19.5%) | 7 (7.6%) | 0.445 |

| Endoscopic disease assessment | |||

| Change in mayo score from baseline (n) | 24 | 48 | |

| Worsening | 3 (12.5%) | 3 (6.3%) | 0.366 |

| Improved | 8 (33.3%) | 24 (50.0%) | 0.180 |

| Stable | 13 (54.2%) | 21 (43.8%) | 0.404 |

| Change in disease extent from baseline (n) | 25 | 49 | |

| Worsening | 3 (12.0%) | 3 (6.1%) | 0.366 |

| Improved | 9 (36.0%) | 14 (28.6%) | 0.514 |

| Stable | 7 (28.0%) | 25 (51.0%) | 0.059 |

| Composite outcome (%) | 36 (39.6%) | 52 (41.9%) | 0.726 |

| Table 3. Univariate analysis of predictors of readmission for a UC flare | ||||

| Factor | Odds ratio | 95% Conf. Interval | P value | |

| Long steroid taper | 1.16 | 0.49, 2.72 | 0.723 | |

| Disease duration | 1.00 | 0.98, 1.02 | 0.614 | |

| The initial dose of Prednisone | 1.02 | 0.95, 1.11 | 0.472 | |

| Initial prednisone dose > 40mg | 2.13 | 0.40, 11.2 | 0.370 | |

| Clinic Follow up within four weeks | 0.67 | 0.25, 1.83 | 0.443 | |

| Steroid use in the last six months | 0.63 | 0.26, 1.56 | 0.328 | |

| Steroid dose escalation within four weeks of discharge | 5.29 | 1.66, 16.8 | 0.001 | |

| Inpatient rescue therapy | 1.96 | 0.50, 7.62 | 0.327 | |

| Table 4. Multivariate analysis of predictors of readmission for a UC flare | ||||

| Factor | Odds ratio | 95% Conf. Interval | P value | |

| Steroid dose escalation within four weeks of discharge | 6.09 | 1.82, 20.3 | 0.003 | |

Discussion

The prescription of immunosuppressive or anti-TNF medicines among steroid-receiving patients did not rise. UC treatment recommendations were released in 2006 and are frequently used by gastroenterologists, who often assess inflammatory bowel disease, to support clinical decision-making. The widespread application of evidence-based treatment guidelines has significantly reduced the time patients with early UC are prescribed steroids.

According to Fukushima (2016), controlling inflammation without producing refractory UC is the main objective of UC treatment (steroid-dependent or steroid-resistant UC). Medications that enable continued symptom control after remission is chosen to treat UC effectively. Among these are salicylazosulphapyridine (SASP), 5-ASA formulations, and topical medications. Despite their effectiveness in causing remission, steroids should not be used as the first treatment for mild to moderate UC, according to clinical practice guidelines. Instead, oral 5-ASA formulations or local treatment are advised. The prescription of steroids for individuals with early-stage UC may have decreased with these criteria in clinical settings. During the trial period, 50% of patients began taking steroids within 60 days after receiving their UC diagnosis. In database research, Targownik et al.(2014) discovered that after 60 days of diagnosis, steroid prescription among IBD patients peaked at 16.8% (Matsuoka et al.,2015). According to (Ilnticky et al.,2003), even though our study’s peak prescription rate was higher than its counterpart, the two studies exhibit similar trends. 124 patients had a prolonged taper and 91 individuals received a short taper out of the 215 patients that satisfied the inclusion criteria. Adverse effects were identical in all cases.Individuals with mild UC instances who show a solid inflammatory response also received prednisolone. 2016’s For moderately severe or worse UC, steroids are usually recommended(Suzuki group,2016). For severe and moderate UC, the readmission rates for the initial therapy after diagnosis were 45.5% and 43.5%, suggesting a direct relationship between sickness severity and treatment response Many UC patients may not need intensive care even during the remission stage after obtaining efficient remission induction therapy According to Andres et al.,(2016). Remission-inducing therapy is consequently valued in the treatment of UC, and the upper strategy, in which aggressive therapy using steroids is started as soon as possible following UC diagnosis, may result in the administration of steroids as soon as possible.

Each medication has a different remission induction therapy duration. Based on the typical recommended dosage and subsequent tapering therapy, this period for steroids should be three months. In this study, the effectiveness of steroids for sustaining remission was shown by the fact that 23.7% of participants continued to take them after six months. The mean decumulation of steroids among these patients was 0.868 mg, indicating that a moderate amount of steroids was provided throughout the six months. If a specific response is not noticed within 1 to 2 weeks of starting oral prednisolone, the treatment recommendations for UC advise patients to move to medication for severe or drug UC. The effectiveness of steroids should also be evaluated early. Even if they are successful, people should switch to other medications to prevent using steroids long-term due to the danger of developing steroid-resistant UC or experiencing unpleasant responses.

The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization advises that individuals with steroid-resistant ulcerative colitis (UC) exhibit clinical symptoms after receiving prednisolone at a dose of 0.75 mg/kg/day for four weeks(Sartor et al., 2004). (Hibi et al.,2003).. Individuals with the drug UC for whom the dosages could be lowered to providing a variety of doses of less than 10 mg/day without triggering a flare-up should consider additional treatment options or changes (Dignass,2012). Also noted are that reduced steroids and placebo did not differ in maintaining remission and were unsuccessful in preventing disease flare-ups and that steroids are useless in maintaining remission. Limiting the use of steroids and shifting to non-steroidal medication is crucial because prolonged steroid usage may result in a variety of adverse side effects (Benchimol et al.,2008) (Huscher et al.,2009)

The only significant predictor, according to our analysis of the variables influencing the prescribing of elevated steroids (total recommended dose of about 1500 mg over six months following commencement of steroids), was the command structure of healthcare organizations (Lennard,1965) (Truelove,1955). Large management structures at medical facilities increased the likelihood of steroid dosage increases (Smolen et al.,2014). As 91.2% of patients received their care within the same facility for a minimum of six months, switching hospitals had less impact on the outcomes. Since UC is classified as an incurable illness, people with UC frequently go to big hospitals with many doctors. Due to the association between heavy steroid use and disease activity (Solberg,2007), individuals with relatively aggressive illness progression may seek treatment in these institutions more frequently due to the association between a large leadership structure and the prescription rate. However, if remission inducement therapy is effective, the subsequent remission phase frequently does not require intensive therapy. Treating and managing individuals with early-stage UC is crucial to prevent refractory UC and uncontrollability. More extensive medical facilities may recommend high-dose steroids to induce temporary remission. Although it has been noted that male patients are more likely to receive a high dosage of steroids, this was not shown in the current investigation. As a surgical intervention in older life is strongly predicted by the use of elevated steroids in the first year following IBD diagnosis, great attention should be made to the steroid dosage from the beginning of treatment.

Management of Moderate to severe ulcerative colitis as Demonstrated in the study

According to Fuming et.al, (2018), the peak onset of UC, a severe inflammatory bowel disease, occurs in early adulthood. The condition has a recurrent and remitting mucosal inflammatory course if left untreated. According to society observational studies, the most of UC patients have a moderate to severe course with various phases of remission or modest activity after diagnosis. 20% of patients who encounter an aggressive course may need to be hospitalized due to significant disease activity. About 15% of people may experience this. In patients with mild to moderate disease activity, the 5- and 10-year accumulated risk of colectomy is 10%-15%; in a subgroup of hospitalised people with symptomatic severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC), the short-term colectomy rates are 25%–30%. The following are indicators of a disease with an aggressive course and a colectomy: young age at diagnosis (40 years old), advanced illness, significant endoscopic activities (existence of large and/or deep ulceration), presence of extra-intestinal symptoms, need for corticosteroids early in the course, and high inflammatory markers. Tofacitinib, TNF- antagonists, anti-integrin agents (vedolizumab), Janus kinase inhibitors (tofacitinib), interleukin 12/23 antagonists (ustekinumab), and immunomodulators are just a few of the medication groups available for the long-term therapy of moderate to severe UC (thiopurines, methotrexate). Generally speaking, if a medicine is effective at causing remission, it is continued as maintenance therapy. This clinical procedure is regarded as standard of care. and it is assumed that if a medication (with the exception of corticosteroids and cyclosporine) is began for the purpose of inducing remission or a response and proves to be successful in doing so, it will be continued for the purpose of maintaining remission,(Ungaro,et al,2017). This guideline covers both the medical care of adult admitted patients with ASUC and the patient treatment of senior outpatients with mild to severe UC. For the onset and maintenance of recovery (for mild to severe UC), the guideline concentrates on immunomodulators, biosimilar, and small molecules, which also reduces the threat of colectomy . As mentioned, the study does not offer distinct suggestions for remission induction and maintenance. Unless otherwise stated, the medications are listed in the order of FDA approval. The study focus on the medical care of senior outpatient clinics with mild to severe UC; and concentrates on the initial management and rescue medication in instances of corticosteroid-refractory illness for adult admitted patients with ASUC. The study recognises the difficulties in identifying moderate clinical symptoms and severity, with varying definitions in clinical practice. Using the AGA recommendations, on the treatment of mild to moderate UC,the study reveals the most unequivocal impacts that short term and long term treatment has on the patients. The surgical therapy of mild to severe UC or ASUC is included in the study.The study contrast IFX and CsA to contrasts its effectivenss on patients suffering from severe and acute ulcerative colitis.

It has been demonstrated in the study that CsA is incredibly helpful in the administration of ASUC. The 2 mg/kg/day dosage is associated with decreased toxicity and equivalent rates of progress to colectomy compared to the 4 mg/kg/day dose, with original trials having predicted response rates of >80%. 24 The main disadvantage of CsA is that it may be hazardous. In particular, there is a chance of nephrotoxicity, seizures (which are frequently accompanied by low serum cholesterol), irregular electrolytes, hypertension, and bacterial illnesses. The drug is frequently saved for patient populations with real potential complications to steroid therapy and those unfamiliar with thiopurine therapy, in which thiopurines can serve as a long-term bridge after discharge. These risks can be reduced to a certain large extent through the analysis of drugs and infection prophylaxis. Despite this, there is still a place for intravenous dosing of 2 mg/kg/day, given its quick onset of action, followed by conversion to oral treatment (5 mg/kg), which is typically used to use for up to three months as a transitional period to an immunomodulatory agent (suppressive therapy or mercaptopurine) while also steroids are weaned. In a randomized trial of 63 patients with moderate-to-severe acute steroid-refractory UC, tacrolimus, another calcineurin inhibitor, was shown to be effective, with response times of 50% and mucosal ability to heal rates of 44% within a week of 2 weeks of treatment (p = ≤ 0.05 and 0.238 versus placebo, respectively). Therefore, an alternative to thiopurine therapy can be considered: CsA with such an arch to tacrolimus after discharge. Recent evidence of its viability allows for a switch to innovative biologic medicines that are not usually taken into account in the treatment of ASUC

Effectiveness of IFX and CsA in contrast

Efficacy, safety, patient or provider preference, and prior use all factor into the choice of CsA or IFX as a rescue drug in steroid-refractory ASUC. The quick beginning of the effect, shorter half-life (7 h as opposed to 9 days), and ability to switch to other concurrent immunosuppressive drugs (thiopurines or tacrolimus) that may be utilized with other innovative biologic therapies, such as anti-TNF medicines, are all advantages of CsA. The benefits of IFX include the lack of other side effects associated with CsA that can be challenging to handle (hypertension, electrolyte disturbances, nephrotoxicity, and seizures) and the ability to track drug levels with a complete sense of thresholds to achieve efficacy outcomes. Two randomized trials that examined the efficacy of CsA and IFX as salvage therapy for ASUC have been conducted. The primary endpoint of the CySIF trial, which randomized 115 ASUC patients who had failed five days of steroid therapy, was treatment failure at seven and Ninety-six days (response, relapse, steroid-free remission, colectomy, death). In this trial, neither the direct result of relapse (60 percent) of the respondents and 54%, p = 0.52) nor the particular outcomes at days 7 or 98 significantly differed between CsA and IFX.

The possible impact on other medicines’ capacity to treat patients rejecting one of these salvage therapies is a crucial factor to consider when selecting salvage therapy for ASUC. According to cohort research from Mt. Sinai in New York, patients undergoing sequential therapy (CsA IFX or IFX CsA) are more likely to experience adverse effects and pass away. Other cohort studies did not support this, and the findings are inconsistent. Using data from 10 studies and 314 participants, a current systematic review measured the pooled rates of potentially relevant: shorter reaction rates were 62.4percent (95% CI 57-68.7%), colectomy rates were 28.3% (95% CI 21.7-34.5%) at three months, severe illnesses were 6.7% (95% CI 3.6-9.8%), and death was 1% (95% CI 0-2.1%). This study also discovered that the accuracy of the data could have been better, making it impossible to make a firm judgment regarding the use of sequential therapy or, if it is, the best possible order in which to administer the various therapies. The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization’s most recent guidelines suggest that a third treatment (or sequential treatment) can be considered in specialized referral centers in some situations. However, there can be no recommendations for or against its use. These studies collectively imply that the efficacy and safety profiles of CsA and IFX are comparable and that the choice of agent to employ depends on a mix of personal preferences, provider familiarity and expertise, and patient-specific considerations.

Surgical emergency treatment

Given the higher risk of mortality when performed urgently in patients with ASUC, the decision to perform a colectomy should not be made lightly. Instead, it should be made in a multidisciplinary setting with colorectal doctors at high-volume centers because it has been demonstrated that the experience and quantity of the surgeon influences surgical outcomes. When a problem has occurred (such as possible perforation, toxic megacolon, or refractory bleeding), an urgent colectomy is most definitely recommended. However, failure of medical therapy is the most prevalent cause of colectomy in ASUC. Although medical management aims to prevent progression to colectomy, healthcare professionals must remember that postoperative problems are more likely when surgery is delayed. It is advised to use a three-step procedure when performing a colectomy for ASUC: total colectomy and ileostomy inside the inpatient care with the rectum left in-situ, corrective surgery 3-6 months afterward with the creation of the ileal pouch and defunct loop ileostomy; and eventually closure of the ileostomy circuit. Female patients of childbearing age represent a particular patient population for which an alternative strategy might be considered. The development of a pouch in these people is linked to a higher risk of infertility. So, until they can start their children, consideration could be given to a subtotal colectomy with postponed pouch development.

Comparative Study of the Treatment

Our initial goal was to assess the potential of systemic oral corticosteroids (Prednisone) and low-bioavailability corticosteroids (beclomethasone/budesonide) to cause remission of mild IBD flare-ups in patients who had received IMM treatment for at least six months (azathioprine, mercaptopurine, or methotrexate). Our second goal was to evaluate this treatment’s long-term efficacy in preventing the requirement for biological medications and surgery and to examine the indicators of responsiveness in this particular situation. From a reference region of 176,208 residents, we used a demographic database to find patients identified with Colitis ( UC and CD) between 1966 and 2016; we only included individuals who had at least six months of IMM therapy in our analysis.

The following variables were collected for a descriptive analysis:

-(UC/CD) IBD type,

– Diagnosis year,

– Where IBD is located about UC and CD by the Montreal classification:

- Left-sided (E2)/ulcerative proctitis/extensive UC (E3) (E1)

- Colonic (L2), ileocolonic (L3), and ileal CD (L1) with or without separate upper disease (L4)

- An infection in the perianal region

– CD behavior as defined by the Montreal classification:

- Penetrating with an inflammatory pattern (B1) and fibro stenotic (B2) (B3)

– An appendectomy

-Smoking habit at the time of diagnosis:

- Smoker: Current therapy and smoking at the time of IMM

- Former smokers: at least six months smoke-free, particularly Non: Never smoked or has not smoked in more than ten years

-Earlier surgery

-Invoking corticosteroids during diagnosis

– IMM therapy

- Azathioprine, mercaptopurine and methotrexate are examples of IMM treatments.

- Duration of IMM therapy up until the administration of corticosteroids and the completion of the follow-up

-Before immunosuppression, biological medication treatment

We noted the following throughout the follow-up:

-The duration and dosage of systemically oral or reduced corticosteroid therapy

– The effectiveness of corticosteroid therapy was characterized as not requiring additional cycles of corticosteroids, treatment intensification, or surgery.

– The period following the usage of corticosteroids during which no rescue therapy was required.

-Any requirement for more corticosteroid cycles, surgery, or biologic medications.

Results

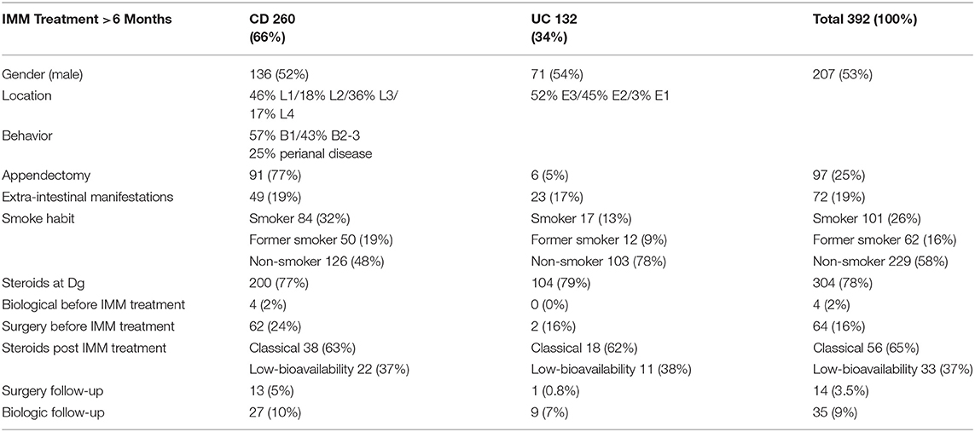

In our population database, which we used to identify 904 patients with IBD from 1966 to 2016, we chose 392 (43.3%) of those who had received IMM treatment for at least six months, with a median time of 82 months (6–271). Among these 392 individuals, 260 had CD diagnoses (66%) and 132 had UC diagnoses (34%). In Table 5, we list the demographic and medical traits of the patients.

During their follow-up, 89 patients (23%) had at least one session of oral corticosteroids, with a four month average length of treatment (1–168 months). Twenty-nine patients (33%) had UC, and 60 patients (67%) had CD; 63% of these 89 patients were treated with systemic corticosteroids, and 37% with reduced oral corticosteroids (p = 0.805).

The Harvey-Bradshaw scale in CD (defined as clinical remission at or below 4 points) and Truelove-Wits index for UC (remission if three stool moves and no rectal bleeding) were used to assess disease activity clinically. Clinical remission was the intended outcome of treatment, and steroids were prescribed to achieve remission in the presence of clinical activity. In the early years (1966–2006), our hospital’s steroid demonstrated a method textbook and GETECCU recommendations, and from 2006 to 2016, it followed ECCO guidelines. Prednisone was used to treat mild to moderate CD or UC, commencing at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day and tapering off starting in week 4 (often by reducing the dose by 10 mg/day each week). The medication budesonide (9 milligrams, tapering during week 4) was used to treat mild to moderate ileitis. Treatment for mild to moderate UC cases included mouth beclomethasone (5–10 mg/day; 1-2 month duration).

The responsible doctor made the decisions for how to treat the patients. From 1966 to 2010, IBD patients were typically treated by the same skilled gastroenterologist. Following the gold-standard ECCO criteria since 2010, the IBD patient care team has stayed the same. Following EMA approval, biologics were available for purchase about 12 months later. Azathioprine was administered at 2.5–3 milligrams in a single dosage, along with 1.5 mg/kg/day of mercaptopurine. Blood testing followed up on both patients frequently (every 3-6 months), but there was no way to determine whether or not metabolites were present.

All data were analyzed using IBM spss19 statistical software for statistical analysis, with a 95% confidence level. Earlier, the information had been collected and analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2010 2010. According to the features and distributions of the variables, the descriptive statistic of the sample revealed the mean (standard deviation), measures of central tendency (interquartile), and frequency (%). If the conditions of use could be verified, the Student’s t-test and corresponding non-parametric tests, Mann-Whitney Standardized tests, or Kruskal-Wallis, if any of the variables was quantitative, were used instead. Distinctions between variables were assessed using the chi-square (Fisher) exam for qualitative variables and the Student’s t-test otherwise. The log-rank alternative hypothesis, which examines the null that the two groups studied share the same survival curves, was used to compare various survival curves based on a diagnosis of UC or CD in the last stage of the analysis. In our population database, which we used to identify 904 patients with IBD from 1966 to 2016, we chose 392 (43.3%) of those who had received IMM treatment for at least six months, with a mean follow-up of 82 months (6–271). Among these 392 individuals, 260 had CD diagnoses (66%), and 132 had UC diagnoses (34%). We outline the patients’ clinical and demographic characteristics.

During their follow-up, 89 patients (23%) had at least one session of oral corticosteroids, with a 4-month average length of treatment (1–168 months). Twenty-nine patients (33%) had UC, and 60 patients (67%) had CD; 63% of these 89 patients were treated with systemic corticosteroids, while 37 percent used low-bioavailability oral corticosteroids (p = 0.805). There were no differences in gender, age, localization of the sickness, perianal illness, appendectomy, extraintestinal symptoms, smoking habits, prior use of corticosteroids, or prior surgery when the factors associated with the requirement for corticosteroid treatment were compared.

CD fibro stenotic (B2) with fistulizing (B3) motifs exhibited statistically significant behavior (p = 0.005). In contrast to patients with an inflammation pattern of CD (B-1), those with fibro stenotic or fistulizing patterns of CD (B2-B3) were double as likely to receive corticosteroids while receiving IMM treatment (odds ratio (OR): 2.284). Four CD patients (1% overall) required biological drug therapy before beginning their IMM treatments (a top-down approach), and this was also related to the requirement for corticosteroid therapy throughout evolution (p = 0.038).

We sought to determine the diagnostic and clinical characteristics linked with a more severe course to correspond with the development of more potent treatments because perianal illness, early age at assessment, and the use of corticosteroids seem to be significant risk factors in patients with CD. Once a patient receives immunosuppressive medication, this characteristic was not linked to our group’s following corticosteroid requirement. Additionally, the presence of corticosteroids at assessment did not indicate that our patients would require additional rescue therapy after taking these corticosteroids. Corticosteroid use should be carefully considered once the patient gets IMM therapy, as is the situation with our cohort. If other therapy options, including the use of biological medications and surgery, have yet to be optimized and are not more successful over the long term, such as more than one cycle of corticosteroid (ideally of low bioavailability), they should never be utilized.

The overall effectiveness of corticosteroid use in the already immunosuppressed individuals with UC or CD, characterized in our research as having no requirement for any additional type of treatment all through the join, was only 35%; consequently, 65% of patients who received corticosteroids will need a new cycle of diagnosis with corticosteroids, physiological drugs, or surgery. Our findings suggest that the patients (EC B2-B3) who will require the most corticosteroids in an immunosuppressed state are also the ones who respond slowly over time and need early biological therapy or rescue surgery. Therefore, individuals with UC whose flare-up is controlled by low-bioavailability corticosteroids may benefit most from employing corticosteroids in individuals already receiving IMM treatment (fewer side effects). Additionally, these individuals with UC had longer-lasting corticosteroid effects than people with CD.

Conclusion

Steroid prescription rates after UC diagnosis demonstrated a trend toward declining after six months. However, we discovered that some patients were taking steroids for almost a year, proving that these medications were employed as maintenance therapy. It is necessary to conduct additional research to determine whether using steroids soon after receiving a diagnosis of UC impacts the dosage of steroids to be used in the future, the start of adverse responses, and the likelihood of UC-related surgical intervention. A doctor can recommend a milder steroid like Entocort (budesonide) to relieve inflammation if your UC exacerbation is mild to severe. Prednisone is robust, but this medication has fewer adverse effects. According to Faudion et al. (2001), Prednisone is intended to combat minor to severe intestinal inflammation and prevent further inflammation for around three months. According to Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, the FDA has cleared the medication for usage for eight weeks. However, it may be prescribed for longer in some circumstances. In addition, one will probably be given a long-term maintenance drug that is not a steroid, such as Lialda (mesalamine), which can take some time to work (Kornbluth et al., 2010). Because steroids are not meant to be taken continuously, one must reduce the dosage when the maintenance drug starts to act. The doctor will most likely gradually reduce the steroid dosage until entirely off it.

Doctors often advise one to use steroids for a brief period, typically eight weeks, due to their substantial adverse effects. One in five individuals does not respond to steroids. We refer to this as being steroid refractory. After three months, if they do not seem to be alleviating the symptoms, your doctor may combine the steroid with an immunosuppressant like azathioprine (Azasan, Imuran), mercaptopurine (Purinethol, Purixan), or methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Trexall). If the UC is severe and ineffective, a doctor may switch to biological medications like infliximab (Remicade) or adalimumab.

(Summers,1979).

When one takes steroids, the adrenals slow down or halt producing cortisol, the body’s natural steroid. It would help if one did not quit using steroids abruptly. Before that, the body must start producing cortisol again (Vestergaard et al.,2002). To gradually wean off the steroid, the doctor will walk one through some tapering-off process.

Truelove et al. (1954) define acute ulcerative colitis as A medical emergency necessitating immediate hospitalization that meets Witt’s requirements. Critical adjuncts in treating severe UC include maintaining proper electrolyte and fluid balance, stopping medications that encourage colonic dilatation, and providing enough nutritional support. For severe UC, intravenous corticosteroids serve as the first line of treatment, and about two-thirds of patients benefit (Powell et al.,2011). On day 3, the reaction to steroids must be evaluated, and clinical rescue treatment or operation should be considered in non-responders or partial responders. A recent randomized trial demonstrated that the effectiveness of both cyclosporin and infliximab in this situation is equivalent (Marshall et al.,1997).

According to Hoes et al. (2009), close collaboration between the gastroenterologist and the surgeon is necessary to manage severe UC best. Surgical is always possible once IV steroids fail, and it should be made available to all patients(Curtis et al.,2006). Such patients must be managed according to a time-bound plan. Surgery should not be postponed for longer than five days after beginning intensive therapy because doing so raises surgical mortality and morbidity.

For individuals with severe UC who are not reacting to medical treatment, surgery is their only remaining choice. Perforation, toxic megacolon, and severe hemorrhage are additional conditions that require surgery. Delaying the choice to have surgery raises the risk of morbidity and mortality from surgery. In previous research, the mortality rate for immediate surgery was very high if the treatment was postponed for longer than five days after an intravenous steroid treatment did not work. In a different Oxford study, more surgical complications were identified if surgery was postponed after more than eight days of medicinal treatment. To make timely judgments on the care of severe UC, a surgeon, and gastroenterologist must work closely together. The intervention would ensure that patients can recuperate from the condition after the intervention.

The most significant consequence of severe UC is perforation, among other complications. Inappropriate complete colonoscopies and postponing toxic megacolon treatment are risk factors. Since abdominal symptoms might be concealed when a patient is using steroids, perforation diagnoses are frequently postponed. As a result, individuals who have severe UC should have their abdominal health thoroughly examined, and stomach radiographs should be taken at the first sign of suspicion. Severe bleeding is one such consequence.

In an emergency, most facilities recommend a three-step procedure. Colectomy and ileostomy, with the rectum left in place, is the surgical method of choice in an acute environment. The whole rectum and lower mesenteric artery must be retained to permit additional surgery. Depending on the surgeon’s choice, the bowel may be brought forward as a mucous fistula or closed in subcutaneous fat. Even in severely ill patients, a subtotal colectomy is a non-invasive treatment that will alleviate a load of severe colitis and restore their health and nutrition. The ideal time to conduct reconstructive surgery is six months following the initial procedure. Ileal pouch development and temporary ileostomy deduction make up the second step. This allows a small number of pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA), which restores regular continuity and is completed in the last phase.

Long-term immunosuppressive usage seems strongly associated with poor wound healing following surgery, which can show up as scar dehiscence, illness following an intestinal leak, or a pelvis abscess after the anastomotic leak. The anastomotic leak has been linked significantly to long-term preoperative steroid use. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine, immunosuppressive drugs, have not been linked to increased postoperative complications. Cyclosporin has not been linked to increased postoperative complications when administered alone. Infliximab (IFX) use and how it affects postoperative courses are controversial and of great interest. According to two studies, there is a connection between IFX and postoperative problems in IPAA patients. The first study was published by the Mayo Clinic and involved a retrospective examination of 254 individuals who did not receive preoperative IFX and 47 patients who did. IFX was independently linked in the multivariate analysis to a higher incidence of the sac and infectious complications.

According to the scientists, IFX served as a stand-in for critically ill patients who were more likely to experience postoperative problems. The study used a case-control study design in the second study conducted by Mor et al. The study reported that individuals with beforehand IFX were three times more likely than control patients to have an early postoperative problem. Patients exposed to IFX had a nearly 14-fold higher risk of developing infectious issues. Other research, including a significant retrospective evaluation of 413 UC patients and CD more than 14 years, has not agreed with the findings of the studies described above.

In this investigation, we discovered no link between IFX and postoperative problems. The study was criticized for having a heterogeneous group with more than 50% of patients getting CD and just 26 individuals with UC exposed to IFX before surgery. Another study that examined the clinical outcome in 141 Cd and uc over ten years revealed no link between IFX exposure and postoperative problems. Steroid use was linked to more infectious problems in the same study. The study was limited because only 22 individuals had been exposed to IFX before surgery. According to a new meta-analysis, Infliximab use is not linked to a higher risk of postoperative complications.

ASUC is a life-threatening emergency that must be identified and treated immediately. It is crucial to risk patients who are most likely to require progression to second therapy if conventional corticosteroid medical therapy fails. Risk factors should be altered wherever possible, and attention should be devoted to excluding manageable triggers and sequelae, such as concurrent infection. Treatment efficacy, whether utilizing IFX or CsA in ASUC, is comparable. The choice will be based mainly on provider comfort and knowledge as well as patient-specific risks for problems and tolerance. The use of more excellent rapid induction to reach peak levels sooner in the therapy algorithm and the utilization of CsA as a transitional drug for newer biologics after hospital discharge are recent developments in the usage of IFX.

References

Andres PG, Friedman LS. 1999, Epidemiology and the natural history of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am.;28:255–281.

Benchimol EI, Seow CH, Steinhart AH, et al. 2008 Traditional corticosteroids for remission induction in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.;16(2): CD006792.

Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Allison J, et al. (2006). Population-based assessment of adverse events associated with long-term glucocorticoid use. Arthritis Rheum.;55:420–426

Dignass A, Eliakim R, Magro F, et al. (2012). Second European evidence-based consensus on diagnosing and managing ulcerative colitis part 1: definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis.;6:965–990.

Faubion WA Jr, Loftus EV Jr, Harmsen WS, et al. (2001). The natural history of corticosteroid therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology.;121:255–9.

Hoes JN, Jacobs JW, Verstappen SM, et al. 2009Adverse events of low- to medium-dose oral glucocorticoids in inflammatory diseases: a meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis.;68:1833–1838.

Huscher D, Thiele K, Gromnica-Ihle E, et al. (2009). Dose-related patterns of glucocorticoid-induced side effects. Ann Rheum Dis.;68:1119–1124

Kornbluth A, Sachar 2010:DB. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American college of gastroenterology, practice parameters committee. Am J Gastroenterol.;105:501–523.

Lennard-Jones JE, Misiewicz JJ, Connel AM, et al. (1965). Prednisone as maintenance treatment for ulcerative colitis in remission. Lancet.;1:188–189.

Fumery, S. Singh, P.S. Dulai, et al.

Natural history of adult ulcerative colitis in population-based cohorts: a systematic review

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 16 (2018), pp. 343-356 e3

Sartor RB, Sandborn WJ, et al., Editor. Kirsner’s textbook of inflammatory bowel disease. 6th ed., Saunders, 2004;280-288

Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR 2014 recommendations for managing rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis.;73:492–509.

Solberg IC, Vatn MH, Hoie O, et al. (2007). Clinical course in Crohn’s disease: results of a Norwegian population-based ten-year follow-up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.;5:1430–1438.

Strehl C, Bijlsma JWJ, de Wit M, et al. (2016). Defining conditions where long-term glucocorticoid treatment has an acceptable level of harm to facilitate implementation of existing recommendations: viewpoints from a EULAR task force. Ann Rheum Dis.;75:952–977

Hibi T, Inoue N, Ogata H, et al. Introduction and overview: recent advances in the immunotherapy of inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(Suppl):36–42.

Ilntckyj A, Shanahan F, Anton PA, et al. Quantification of the placebo response in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1854–1858.

Fukushima T., editor. (2016). Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of Japan (CCFJ): clinical practice guidelines for ulcerative colitis. 3rd ed., Bunkodo

Marshall JK, Irvine EJ. 1997Rectal corticosteroids versus alternative treatments in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut.;40:775–781.

Matsuoka K, Kobayashi T, Ueno F, et al. (2015). Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Gastroenterol. ;53:305-353.

Research study of intractable inflammatory bowel disease by Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare research group (Suzuki group): Diagnostic criteria and treatment guidelines for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, Supplemental volume, Annual report; 2016.

Powell-Tuck J, Bown RL, Lennard-Jones JE. 2011:A comparison of oral prednisolone given as single or multiple daily doses for active proctocolitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1978;13:833–837. [5] Ford AC, Bernstein CN, Kham KL, et al. Glucocorticosteroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol.;106:590–599.

Summers RW, Switz DM, Sessions JT Jr, et al. 1979; National cooperative Crohn’s disease study: results of drug treatment. Gastroenterology. 77:847–869.

Targownik LE, Nugent Z, Singh H, et al. 2014 Prevalence of and outcomes associated with corticosteroid prescription in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory Bowel Dis.;20:622–630.

Truelove SC, Witts LJ.. 1955 Cortisone in ulcerative colitis: final report on a therapeutic trial. Br Med J.;2:1041–1048.

Vestergaard P, Mosekilde L. 2002:Fracture risk in patients with celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis: a nationwide follow-up study of 16,416 patients in Denmark. Am J Epidemiol.;156:1–10

write

write