Introduction

When the Great Recession struck, Congress passed the Recovery Act (commonly known as the Stimulus), a public law designed to help businesses and individuals recover from the economic downturn. As a result of the recession, a substantial number of employment were at risk in the United States. Supplemental funding for employment preservation and creation, scientific research, energy efficiency and infrastructure investment as well as help for the unemployed are all described in the Act’s subtitle (United States, 2009). ARRA’s history, implementation, and influence on industry and society must be examined in order to evaluate the Act’s results as well as provide recommendations for future policymakers….

Public policy that affects the business sector must be examined for signs of market failure or underperformance in order to determine whether the government’s choice to implement the policy was based on this. Within this concept, government actions, attempts, and policies to implement additional controls on the market and enterprises are a result of the public’s inquiries based on market failure. Inaccurate information and monopoly are two examples of these failures. As a result of these rules’ stated goals often not being met, researchers have underlined the significance of a critical approach to regulatory analysis in light of this. It is possible to claim that intervention is a government failure if the market-failure explanation is insufficient. During the Great Recession, academics and government officials thought that the United States needed a law requiring severe market intervention. Market failure at least partially justifies this legislation. Its measures, the market’s response, and the actual results are all under question.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act 2009 (ARRA)

In retort to the 2008 Great Recession, Congress passed the ARRA (American Recovery and Reinvestment Act) as a measure of economic stimulation. “Obama stimulus” is another common name for the “stimulus package of 2009.” Government spending were part of the ARRA package in order to counter the effects of the 2008 recession on employment losses. Arranged under the ARRA, a huge infusion of federal funds was made to both generate new employment opportunities and replace those lost during the Great Recession of 2007. The decrease within private investment during that year was made up for by the increase in government spending.

During the months running up to inauguration of President Obama’s around January 2009, legislators began working on the bill. With the help of congressional staffers and an expedited amendments process on January 28, 2009, the bill was passed inside House of Representatives. On February 10th, the US Senate passed its version of the bill (Brass, Clinton T. et al. 72).

It was only after intense conference discussions that Democratic congressional trailblazers finally settled to reduce the bill’s expenditure to win over some Republicans. Since World War II, the bill’s ultimate cost of $787 billion has been the greatest anti-recession expenditure package. On February 17, 2009, President Obama officially signed the legislation to law (Brass, Clinton T. et al. 72). 3

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act Aims

A few of the ARRA’s most important programmes include (Staal, Klaas, 35):

- There will be $800 in further tax relief for families, and the substitute minimum tax shall be protracted for an additional $70 billion.

- Over $120 billion in increased investment on infrastructure projects4

- Healthcare expansion, incorporating $87 billion in help to states to assist cover higher recession-correlated Medicaid costs5. 5

- More than $100 billion within education spending, counting teacher compensation in addition to Head Start.6

How It Changed or Constrained Behavior

Early reaction was a mixture of negative along with positive, largely along party lines however with a significant scale of good-faith debate amongst economists as to a prudence and projected outcomes of enormous fiscal stimulus, which was the ARRA.

The stimulus expenditure was not enough to get the economy past recession, according to supporters. New York Times op-ed columnist Paul Krugman professed the ARRA a premature success— “working just about the way textbook macroeconomics suggested it would—with its sole flaw being that it didn’t go far enough in recovering the U.S. economy.” He claimed, the stimulus did aid the economy get back on its feet, with GDP growing at a quicker-than-anticipated pace at the moment of his writings. In spite of this, the GDP growth rate was not strong enough to overturn unemployment during the years ahead.. 7

Large-scale government expenditure, according to ARRA’s detractors, would be wasteful and hindered by red tape. Even if the stimulus hasn’t yet kicked in, the economy is exhibiting early indications of recovery, according to Lee Ohanian’s Forbes magazine opinion piece, “The $787 Billion Mistake,” published in June 2009. “The economic grounds for the ARRA were badly dated and erroneous,” he asserted, and he believed, government incentives towards private spending in addition to hiring could prove more potent than flooding a market with unwarranted funds (Bremmer, Ian).

The lack of a compelling counterfactual scenario makes it impossible to evaluate the ARRA more than a decade later. ARRA’s impact on the economy is impossible to predict with any degree of certainty. The most consistent approach to do this is to contrast actual results to the substitute economic estimates that were employed to justify ARRA.

Gregory Mankiw, a Harvard economist along with others pursued the real U.S. unemployment rate versus projections made by ARRA promoters at the President’s Council of Economic Advisers during the months subsequent to the Act’s adoption. There was no comparison between this and the baseline “no-stimulus” scenario or the lower forecasts that pretended to highlight the projected advantages of significant new federal expenditure, as the actual unemployment numbers showed. This shows that the ARRA may have contributed to the slowdown of the economic recovery by significantly increasing unemployment rates (Greg Mankiw).

L-shape recovery best describes post-Great Recession economic settings within the United States, which have enhanced since 2008. It took four years for the economy to recover from recession, also nearly eight years to recuperate from unemployment. U.S. government stimulus plans in 2020 and early 2021 were the result of dealing with the pandemic’s impact and a new round of issues. An increase in unemployment and the closure of many small enterprises were both a direct result of the financial crisis (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics). The CARES Act of 2020 and the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 (Congress.gov;.1213 ) have had a positive impact on the economy, which began to show signs of recovery in the first quarter of 2021.

Theoretical Rationale for the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act 2009

For more than three decades between 1883 and 1946, Keynes served as a leading policy analyst and an influential economist. After his fundamental paper`s publication, “The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money,” in 1936, he became a foundational figure in modern macroeconomics. For Keynes, governments should intervene when the economy is at risk. According to “General Theory,” full employment is only achievable through government policy and public investment because the economy is constantly unstable. To Keynes, a financial crisis necessitated the government’s role in filling the gap between the economy’s potential output and its actual output.

Cambridge University professor and Treasury employee John Maynard Keynes served as a civil servant for the British government in the early 1900s. It was his 1919 book “The Economic Consequences of the Peace,” which criticised aspects of the Versailles Treaty and predicted Germany’s post-World War I financial instability, that made him famous. His study of post-war unemployment in Britain led him to write “General Theory” during the Great Depression, and it was the fruit of this research. This served to cement Keynes’ legacy and the development of Keynesian economic theory during the Great Depression.

The 1944 Bretton Woods’s pact that founded the World Bank and the IMF and established a system of fixed exchange rates, was another one of Keynes’s contributions. With unemployment exceeding 7 percent, the economy declining, and big banks full of soured assets as of bad mortgages, recent contrasts to a subsequent Great Depression have permeated within the US.

President Obama pushed Congress to rapidly enact a $787 billion economic stimulus measure after inheriting one of the worst financial climates in decades. States are given billions of dollars to pay for services like infrastructure repair and other programmes, as well as increased unemployment benefits, and lower taxes for many Americans, as part of ARRA.

According to Bruce Perlman, the formalisation of these ideas by Keynes is the primary source of the idea that the government should spend or cut taxes in order to boost the economy. By simply spending money, the government can raise demand in a downturn like we are currently experiencing. Because we have so many people looking for work and so much extra capacity in our factories, the argument goes, we’ve got plenty of resources available when the economy is down. The government can spend money in that situation. That was where [Keynes] stood out the most.

The economist revolutionised the way the world viewed economic downturns. Economic theory prior to Keynes held that markets would eventually correct themselves and that all you had to do was wait it out (Young and Russell, 452). Keynes claimed that a recession may become self-reinforcing, and said that waiting through a recession can lead to a negative spiral that erodes capital. ‘ Consumer spending, investment, and net exports, which Keynes considered to be the three primary pillars of the economy, all begin to falter when the economy as a whole is faltering.

Skeptics argue that the Obama administration’s stimulus plan is based on a misguided application of Keynesian economic principles. However, Young and Russell, (452) argued that the government should help the economy by rescuing failing banks, but that he was wary of government spending as an economic stimulus. “Keynesian ideas on using government spending as a stimulus will not achieve the effects advertised,” writes Young and Russell (454) Barro’s research reveals that the multiplier effect, which proponents of Obama’s stimulus believe will increase government expenditure by providing pay for workers, does not exist.

Wartime spending has frequently been cited as evidence that government spending helped the US economy recover from its Great Depression. Barro, on the other hand, believes that the government’s war spending reduced the multiplier effect because it came at the expense of other sorts of investment.

Defense spending has a normal multiplier of 0.8, which means that 20 cents of every dollar spent on defence comes at the expense of private consumption, investment, etc (Perlman, Bruce 122). Although precise estimates are difficult to come by, the projected multiplier for non-defense purchases is near zero. Only three Republicans voted for the stimulus plan in Congress: Arlen Specter, Susan Collins, and Olympia Snowe, all moderates. Perlman, Bruce (121) agrees with the other Republicans that tax cuts are the greatest approach to stimulate the economy.

The critics of Keynesian economics are also Keynesians, according to Perlman, Bruce (121). Tax cuts under President John F. Kennedy were envisioned as a Keynesian boost, according to Dean Baker. Perlman, Bruce (124) remarked that Keynes emphasised a fact about economics that is as pertinent today as it was during the Great Depression: economics are driven by psychology. ” What Bruce Perlman calls ‘animal spirits,’ or’spontaneous optimism’ (Perlman, Bruce) is at the heart of economics (123). He claims that if a company relies just on financial growth, it will fade and die. “The only way to grow is to maintain a sense of optimism.”

The Keynesian Cross Model

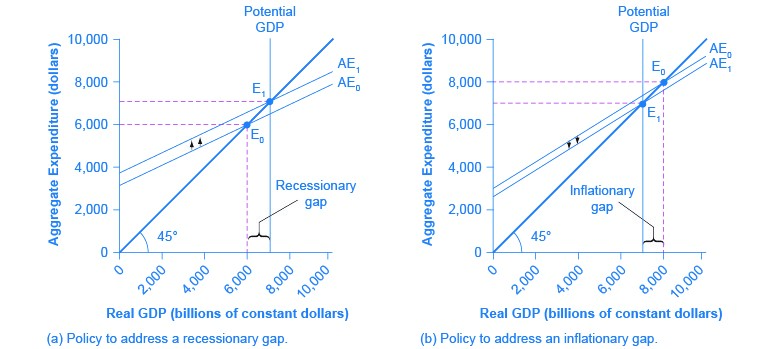

Expanding fiscal policy boosts aggregate demand (or expenditure) in the Keynesian Cross Model, whereas contractionary fiscal policy reduces it. Keynesian economics, on the other hand, does not account for changes in the price level. In contrast, the Keynesian model takes into account the multiplier effect, which means that an initial shift in government spending (or taxation) has a higher impact on output and income in the economy as a whole than the AD-AS model does.

In the last chapter, we saw that fiscal policy’s role is to close the recessionary gap or the inflationary gap, depending on the situation. In order to close a recessionary gap, an expansionary fiscal policy would be needed, lifting the aggregate expenditure function from AE0 to AE1. To close an inflationary gap, a reduction in the aggregate expenditure function from AE0 to AE1 would be suitable, as seen in the second panel.

Addressing Recessionary and Inflationary Gaps

a) A recessionary gap exists if equilibrium is reached at an output lower than potential GDP. In this instance, an expansive stance is warranted.

b) A contractionary strategy is appropriate if the equilibrium is reached at an output above potential GDP.

These concepts can also be demonstrated algebraically. Remember that in THE economy having no foreign or public sectors, equilibrium output and income can be stated as:

Y=1mps×(Ca+I)

The “marginal propensity to save” is mps, “autonomous consumption” is Ca, and investment is I.

Assume we compute equilibrium income and output (Y) using the following formula: mps = 0.5, investment = 1,000, as well as autonomous consumption = 2,000.

Y=10.5×(2000+1000)=2×3000=6000

Assume we assume potential GDP is 7,000, in which situation there is a 1,000-point declining gap. You might recall the economy doesn’t require $1,000 in additional spending to bar the deficit due to the multiplier effect. Instead, 1,000 divided by the multiplier is all that is required (2). We can see this by looking at the expansionary financial policy of a $500 increase in G (government spending):

Y=1mps×(Ca+I+G)

Then

Y=10.5×(2000+1000+500)=2×3500=7000

A tax decrease would, of course, be able to close the disparity. Without further complicating the math, we might ask: with how much could taxes have to be decreased to achieve similar effect as our $500 government spending increase? The difficulty here is that part of the additional disposable income that a tax decrease would provide would be preserved.

Because the mps in the case above is 0.5, 50 cents for each dollar of tax decrease could not be expended, resulting in no gain in output. What this means is that we could require tax cut which, when multiplied with marginal tendency to consume (which tells us how much of the money is really spent), results in a $500 boost in spending. As a result,

Tax Cut=Increased Spending Neededmpc

In this case, that comes out to:

5000.5=1000

Since only a half of that shall be spent (other half will be kept), a 1,000 dollars tax cut shall initially bring about a $500 spending increase, which shall subsequently double to raise income and output by 1,000 dollars, just as the 500 dollars government spending increase did.

Empirical Evidence about Effects of Economic Stimulus Act Of 2008

If you inquire on economists in Obama administration, they are almost unanimous in their belief that the 2009 stimulus package was a success. However, critics of the stimulus claim that this evidence is unreliable. Models that “substitute assumptions for identification” are used in the administration’s studies. Experiments where the government adjusts the transfer in a novel method —while other elements remain the same—are needed to understand the economic implications of transfers, but these events are rare.

To be sure, studies and studies based on models, both of which have been challenged, have been done to establish the impact of incentive on output and employment. 6 of the 9 studies I discovered conclude that stimulus had a large, positive impact on growth and employment, while the other three indicate that impact was either negligible or hard to discern. Five papers use “econometric experiments,” which use empirical data to separate the influence of the stimulus from other factors. Instead, four of them employ modelling.

Each method encounters its own set of issues. Endogeneity is a word used by social scientists to describe the fact that a variable whose influence we are striving to verify (the stimulus) may be changed by the thing we’re seeking to analyse its influence on (state of economy). Within this scenario, this signifies that econometric reports may need to account for the verity that harder-stricken areas are more likely to receive stimulus funding. This tells nothing concerning the stimulus’ efficacy, but it can make statistical evaluations of it difficult.

Each study has its own strategy for dealing with the endogeneity issue, several of which remain more operative than others. However, no matter what corrections are used, it is impossible to execute a flawless experiment with chaotic, practical data that restricts what the research can imply. Three of the 5 econometric studies discussed here find that stimulus had significant positive influence, while the other two conclude that it had no effect at all.

The modelling studies compare results of policy change (such as stimulus package) to the outcomes of baseline wherein the alteration wasn’t ratified using series of equations or an equation designed to simulate that economy. This removes the complication of econometric evaluation by allowing the production of a convenient, stimulus-free counter-factual against which the stimulus bill’s results can be compared. However, it also ignores the real variations in output and employment which occurred once that stimulus was enacted. Additionally, there is much disagreement in economics occupation regarding macroeconomic modelling, and academics who disagree with value of that model utilized in any of these studies can be found. Three of the four modelling studies find that stimulus had considerable positive influence, whereas the fourth implies a positive but minor effect.

Before we go into the studies, there’s one more technical point to address. Many of these studies estimate the “multiplier” of a specific type of stimulus degree. Amount GDP is raised by a dollar of the kind of spending is the “multiplier” of that programme. One among the econometric analyses estimates that Medicaid aid unto states comprised in stimulus has a multiplier of 2. This indicates that for each dollar disbursed on Medicaid, the economy grew by 2 dollars. Any constructive multiplier suggests a stimulative programme; nevertheless, the larger the multiplier, the extra cost-efficient the action.

That stimulus had a favourable, statistically considerable effect upon employment, according to Feyrer, James, and Bruce Sacerdote. The impacts differed depending on the sort of spending. Support to nations for law enforcement and education had little influence, but aid unto low-income individuals as well as infrastructure spending had large effects. Low-income expenditure had a multiplier of 1.95 up to 2.30, infrastructure spending devised a multiplier of 1.85, and the overall stimulus had a multiplier of 0.46 to 1.06.

Chodorow-Reich, Gabriel et al. (140) the stimulus’s state fiscal aid component, which raised federal Medicaid similar funds, had a major positive impact upon employment. Additional similar funds resulted in an increase of 3.5 work-years for 100,000 dollars spent, with a multiplier of roughly 2.

According to Daniel Wilson’s (270) work, stimulus generated 2 million employment in the 1st year in addition to 3.2 million as of March 2011. Jobs multiplier differs significantly depending on if stimulus expenditure is stated to move to particular recipients, is obliged to the recipients, or it has been disbursed to the recipients. Approximations range from 4.8 for a metric based on proclaimed spending up to 25.3 for one founded on definite payments. The private segment, local and state government, along with construction segments all exhibited constantly beneficial benefits, although the impact on health, education, as well as manufacturing depended on if one considers payments, obligations, or announcements.

According to Reichling, Felix, the stimulus generated amid 1.6 million as well as 4.6 million jobs in the first quarter of 2013, raised real GDP to 3.1 percent by 1.1, as well as reduced joblessness to 1.8 percentage points by 0.6. Klein, Barbara, and Klaas Staal (400) point out that by the 3rd quarter in 2010, stimulus has saved or produced 2.7-3.7 million jobs.

According to Tas, Bedri Kamil Onur, that stimulus increased real GDP with 3.4 percent in 2010, cut joblessness with 1.5 points of percentage, and generated about 2.8 million jobs. Both government purchases and tax transfers have relatively minor beneficial influences on growth, according to Oh, Hyunseung, and Ricardo Reis. Tax transfers are estimated to have a multiplier of 0.02 to 0.06, while government purchases have a multiplier of 0.06, via Reis and Oh point out that a further detailed study suggests transfers remain slightly extra stimulative compared to purchases.

Conley, Timothy, and Bill Dupor came to the conclusion that the stimulus had no statistically meaningful impact on job creation. It is believed 450,000 government employment were generated and/or saved, whereas 1 million private segment jobs were averted or destroyed. Taylor, John (698) shows that the stimulus package’s tax transfer provisions, as well as earlier stimulus sets during the 2000s, didn’t result in a momentous consumption increase, and that spending supplies, particularly aid to local and state governments, didn’t result in a significant rise in government acquisitions. Taylor infers that the stimulation was ineffective.

None of the studies are perfect, as the descriptions above demonstrate. However, while the optimistic research back the conclusion that that stimulus was effective, there is cause to disbelieve that the negative studies back the deduction that it was ineffective. Conley along with Dupor discovered a negative influence on productivity and employment, but their findings are not statistically significant, as they admit and as critics of the study have pointed out. Taylor showed that stimulus didn’t considerably rise government purchases, although this outcome could be coherent with stimulus raising output and employment, as Noah Smith claimed. Reis and Oh discovered a tiny tax transfers multiplier like those in stimulus package, however their model provides estimates of crucial quantities which are empirically dubious, as they admit. Using more believable values results in a much higher multiplier, indicating that the package remained more efficient than the predicted model. Because of these concerns, I’m disposed to assume that the stimulus worked based on the majority of evidence.

Evaluation of the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act 2009

The primary goal of policy analysis is to answer the question, “Did the policy work?” This is a particularly difficult issue to answer for policies aimed at major economic changes. Economic systems are enormously complex systems with a vast number of components and impacts, making any change difficult to forecast, which is why predictions frequently fail. When dealing with direct government funding, analysts must establish whether good and bad phenomena observed in the area where the funding was applied were caused by the funding or would have occurred regardless owing to other factors. This issue is exemplified by the ARRA. Experts are still divided on whether the Act had an impact on the dynamics of the US labour market and business because no one knows how the recession would have unfolded if the Act had not been passed.

The United States was founded on the free market premise. Any government initiative to impose extra rules on the economy or otherwise intervene with it is met with apprehension by businesses and society. The ARRA’s extensive provisions were justified by the harsh circumstances of the Great Recession, which explains the law’s speedy passage. Funds were quickly provided and needed to be spent by targets (e.g. WIAs) on federal, state, and local levels within short timeframes, as the implementation study revealed. All of this was done in order to stimulate the economy actively so that short-term gains might be seen as quickly as possible. Hundreds of thousands of jobs were preserved and generated, real GDP increased, and economic efficiency was improved. As a result, the majority of specialists believed that the intervention was well-founded and effective. The policies’ fundamental strength was that they adhered to Keynesianism’s academically investigated and recognised principles, with the strategy of stimulating the economy by investing in the public sector being closely followed throughout the Act’s provisions.

The ARRA’s detractors said that the policy’s fundamental flaw was an early error in the policy design. According to some economists, the assumption was that government spending could not assist strengthen the economy, thus that the ARRA’s ability to achieve its primary goal was questioned. “We the undersigned do not believe that additional government expenditure is a method to improve economic performance,” stated 200 US academics, including three Nobel Prize winners in Economics, in a letter to President Obama (Cato Stimulus, 2009). “Policymakers should focus on changes that reduce impediments to work, saving, investment, and production to boost the economy,” the analysts stated.

The best approaches to use fiscal policy to enhance economy are lower tax rates and a reduction in government load. Some supporters of the ARRA criticised it as well, but this time for the inadequacy of government expenditure. Some economists stated that if more money had been spent on job-supporting measures, the ARRA could have protected and generated far more jobs. The lack of direct metrics was another facet of the Act that economists criticised. To balance the slump, some say that consumer spending and unemployment should be stimulated more directly. By the end of 2009, however, a huge number of US economists, including six Nobel Laureates, claimed that the economy would have been worse if the ARRA had not been passed.

For future policymakers, the ARRA sets a good example. First and foremost, having a sound theoretical foundation can be gained from the Act’s design, implementation, and impact. Prominent economists recommended the Stimulus as a well-founded solution to the recession. It was also focused on both short- and long-term outcomes, which legislators should always aim for. Its provisions were overwhelmingly supported by liberal lawmakers, indicating a strong political consolidation that invariably reinforces laws. Because it was the largest intervention in the US economy since the Great Depression, politicians needed a lot of guts to pass the Act. However, others have criticised the Act for not being broad enough. In addition, less time was spent in Congress examining the Act than had been anticipated. Poor decision-making is always a concern when there is a lack of consideration. One of the ARRA’s flaws that should be studied by future policymakers is the hurry with which the bill was passed.

Works Cited

Perlman, Bruce J. “The ARRA of Our Ways.” State and Local Government Review 41.2 (2009): 120–122. State and Local Government Review. Web.

Bureau of Economic Analysis. Gross Domestic Product, Third Quarter 2021 (Second Estimate); Corporate Profits, Third Quarter 2021 (Preliminary Estimate). (2021). Web

Brass, Clinton T. et al. “American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5): Summary and Legislative History.” American Recovery and Reinvestment Act: History, Overview, Impact. Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2010. 71–117. Print.

Bremmer, Ian. “State Capitalism and the Crisis.” McKinsey Quarterly (2009): 1–6. McKinsey Quarterly. Web.

Chodorow-Reich, Gabriel et al. “Does State Fiscal Relief during Recessions Increase Employment? Evidence from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 4.3 (2012): 118–145. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. Web.

Congress.gov. “Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021.” (2021). Web

Congress.gov. “CARES Act”. (2021). Web

Conley, Timothy, and Bill Dupor. “The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act: Public Sector Jobs Saved, Private Sector Jobs Forestalled.” Journal of Monetary Economics October 2010 (2011): 1–36. Print.

Feyrer, James, and Bruce Sacerdote. “Did the Stimulus Stimulate? Real Time Estimates of the Effects of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.” NBER Working Paper Series 2011: 16759. NBER Working Paper Series. Web.

Greg Mankiw. Accountability? (2009). Web

Klein, Barbara, and Klaas Staal. “Was the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act an Economic Stimulus?” International Advances in Economic Research 23.4 (2017): 395–404. International Advances in Economic Research. Web.

Oh, Hyunseung, and Ricardo Reis. “Targeted Transfers and the Fiscal Response to the Great Recession.” Journal of Monetary Economics 59.SUPPL. (2012): n. pag. Journal of Monetary Economics. Web.

Reichling, Felix. “Estimated Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act on

Employment and Economic Output in 2013.” American Recovery and Reinvestment Act: Economic Impact Five Years Later. Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2014. 81–94. Print.

Staal, Klaas. “State-Level Federal Stimulus Funds and Economic Growth: The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.” International Advances in Economic Research 26.1 (2020): 33–43. International Advances in Economic Research. Web.

Tas, Bedri Kamil Onur. “How Can Recessions Be Brought to an End? Effects of Macroeconomic Policy Actions on Durations of Recessions.” SSRN Electronic Journal (2012): n. pag. SSRN Electronic Journal. Web.

Taylor, John B. “An Empirical Analysis of the Revival of Fiscal Activism in the 2000s.” Journal of Economic Literature Sept. 2011: 686–702. Journal of Economic Literature. Web.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Economy at a Glance”. (2021). Web

Wilson, Daniel J. “Fiscal Spending Jobs Multipliers: Evidence from the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 4.3 (2012): 251–282. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. Web.

Young, Andrew T., and Russell S. Sobel. “Recovery and Reinvestment Act Spending at the State Level: Keynesian Stimulus or Distributive Politics?” Public Choice 155.3–4 (2013): 449–468. Public Choice. Web.

write

write