Natural disasters such as earthquakes, floods, and hurricanes can have devastating impacts on individuals and communities, resulting in loss of life, injury, homelessness, and extreme distress. In times of such intense suffering, many turn to religion for comfort, meaning, and coping. The religious comfort model proposes that religion helps soothe people’s fears and grief by offering a sense of meaning, control, and divine support to counter feelings of randomness and helplessness. The religious comfort model proposes that religion cushions the blow of natural disasters by offering meaning, community, coping strategies, and continuity with the divine that alleviates suffering and empowers resilience.

The Religious Comfort Model proposes that religion provides comfort and relief from anxiety during times of stress. Specifically, the model suggests that having a relationship with a higher power allows individuals to feel cared for, loved, and protected, even when faced with uncertain or threatening situations. This sense of comfort and security helps manage negative emotions and maintain well-being (Sibley & Bulbulia, 2012). Thus, the central tenet is that religious belief systems, rituals, and communities function as coping mechanisms that alleviate distress and grief while giving meaning and purpose to challenging life events.

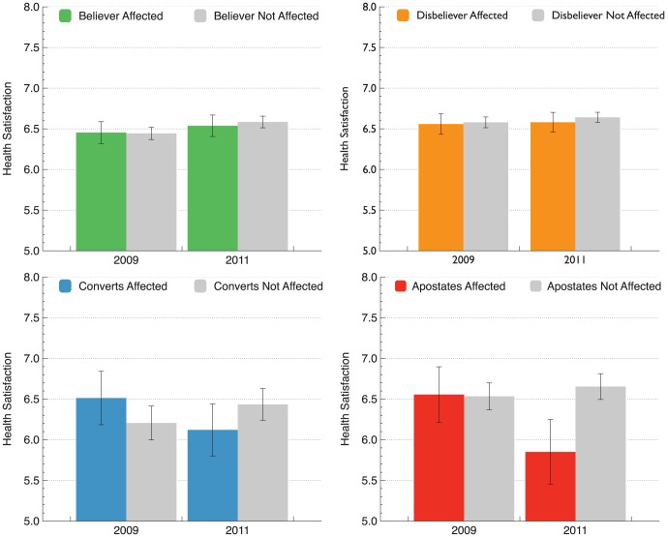

One way in which religion can affect people during and after natural disasters is by providing meaning and explanation for natural disasters. In grappling with the destruction natural disasters cause, people may turn to religion to try to understand why these events occur. Despite the damage to churches, Sibley and Bulbulia (2012) found that religious faith increased among those impacted by the Christchurch quake. Moreover, Reverend Frank Bartleman, chronicling the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, interpreted the disaster as God’s judgment on a sinful city (Sibley & Bulbulia, 2012). Such religious frameworks help make sense of suffering, lending order and meaning to events that might otherwise seem random or meaningless, as illustrated in Figure 1. They give people a lens through which to process human tragedy.

Figure 1: Comparison of changes in self-reported health status between 2009 (pre-earthquake) and 2011 (post-earthquake) among individuals in Christchurch, New Zealand, who were affected versus unaffected by the earthquakes (Sibley & Bulbulia, 2012).

In addition, religion encourages community bonding and support. Shared religious identity unites those impacted by disaster into communities of meaning and mutual care. For instance, early Pentecostals interpreted the 1906 San Francisco quake as ushering in the last days, binding them together in an urgent spiritual movement (Sibley & Bulbulia, 2012). Organized religious relief efforts also provide tangible aid to victims during a crisis. This can be manifested in church-led donation drives and rebuilding projects. Moreover, through rituals like memorials and funerals, religion offers grieving individuals and communities opportunities for collective mourning and consolation.

Furthermore, religion promotes positive coping methods. Religious perspectives can transform interpretations of disaster from meaningless suffering to opportunities for spiritual growth. As Sibley and Bulbulia (2012) suggest, increased religious faith after disasters may help victims positively reconstruct the meaning of such events. Buddhist or Christian views of adversity as spreading compassion could lend deeper purpose. Moreover, belief in an afterlife or ultimate divine justice provides hope beyond earthly destruction. This syncretic blending of diverse religious beliefs and practices, as seen in Indonesian Islam, allows people to draw meaning and coping strategies from multiple faith traditions (Krakatoa, n.d.). Nevertheless, while doubts arise concerning whether higher meaning justifies preventable harm, faith may spur perseverance.

Finally, religion helps in navigating loss and doubt in times of disaster. Religious beliefs and rituals can profoundly impact human experiences and coping mechanisms during and after natural disasters. Religious communities often provide solidarity and meaningful rituals to cope with grief after a tragic loss of life (Chapter Eleven, n.d.). Sacred burial ceremonies help mourners find closure. Thus, religious worldviews shape disaster responses from consoling grief to questioning deeply-held assumptions, where the impacts are multilayered.

Therefore, from explanatory frameworks to solidarity and care, religion profoundly shapes how people endure and recover from natural disasters. By engaging human vulnerability and aspiration, religious traditions offer vital resources for resilience when calamities and disasters strike.

References

Chapter Eleven. (n.d.). Ripples on the Surface of the Pond. Material Provided.

Krakatoa. (n.d.). Material Provided.

Sibley, C. G., & Bulbulia, J. (2012). Faith after an earthquake: a longitudinal study of religion and perceived health before and after the 2011 Christchurch New Zealand Earthquake. PloS one, 7(12), e49648. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0049648

write

write