Abstract

This study examines the complex link between inhibitory control and sketching in youngsters on familiar and unexpected topics. Inhibition has been studied in children’s artistic development. Our research intends to fill methodological gaps and expand the study of inhibition’s effects on children’s drawing ability. The study’s reasoning is the cognitive demands on children when sketching familiar versus unexpected themes and the goal of understanding inhibitory control in creative preferences. We used a correlational, experimental approach to study 30 children aged 3½ to 5½ using drawing activities and a Day/Night challenge. A significant connection (p(0.001)) supports the idea that inhibitory control and difference scores are strongly correlated. The findings confirm the “Behavioural Inhibition account.” by showing that inhibitory control affects children’s sketching habits. Due to age restrictions and correlational analysis, interpretation should be cautious. The study illuminates children’s complicated inhibition and drawing dynamics.

Introduction

Investigating children’s artistic cognition processes involves the complex relationship between inhibition and sketching. This study examines the complex link between inhibitory control and sketching, concentrating on known and novel subjects. The introduction provides a comprehensive overview of the research subject and emphasizes the importance of understanding children’s artistic expressions’ cognitive mechanisms. As the story progresses, a comprehensive analysis of field research emphasizes studies that shed light on the complex relationship between inhibition and sketching. Children’s creative development has been studied, and the cognitive processes involved in depicting familiar and unexpected subjects need attention. The current study expands on previous research by focusing on inhibition in children’s art (Freeman & Janikoun, 1972). This study builds on earlier research by resolving methodological flaws or expanding the topic of investigation.

The discovery that youngsters may have different cognitive demands while drawing familiar subjects like a person versus a dog inspired this study. The theory emphasizes the necessity of understanding the cognitive processes involved in modifying drawing schemas (Siegler et al., 2017). This study aims to answer unanswered theoretical questions, address methodological flaws, and improve our understanding of how children draw in the face of different cognitive demands. As we proceed, the rationale, objectives, and analytical technique used to unravel the complicated dynamics between inhibition and drawing in children will become evident.

Contrast between the two accounts

The text compares children’s development of attributing incorrect beliefs to others. Traditional elicited-response tasks, such as the Sally-Anne paradigm, imply that children can assign incorrect ideas about age 4 (Baillargeon et al., 2010). These activities require children to answer direct questions about an agent’s erroneous belief, showing awareness of mental state. This perspective matches infants’ psychological reasoning system subsystem-2 (SS2), which attributes reality-incongruent informational states to erroneous beliefs. According to this framework, SS2 launches in its second year.

However, recent studies using spontaneous-response tests like violation-of-expectation and anticipatory-looking tasks dispute that false-belief understanding develops around age 4. Studies like the false-belief-green condition show that 2-year-olds can predict an agent’s behavior based on a false assumption about an object’s location (Baillargeon et al., 2010). These data suggest that false-belief attribution begins sooner than previously thought. According to spontaneous-response tasks, 13-month-olds can assign incorrect beliefs about an object’s position, expanding false-belief understanding. This alternate view challenges the conventional view and invites a reevaluation of when children first grasp the intricacies of incorrect beliefs, requiring new theoretical frameworks on baby psychological reasoning.

Rationale

The need to understand inhibition, executive function, and children’s early artistic development drives this research. Cox & Parkin (1986) and Simpson et al. (2019) have shed light on children’s drawing ability, notably inhibition. These studies have contributed but highlight the need for a more thorough understanding of children’s artistic development. Simpson et al.’s explanation of inhibition’s intensity and persistence provides a persuasive framework for understanding inhibitory tasks’ effects on child development. According to Panesi & Morra (2018), working memory and executive function affect children’s drawing versatility. Building on Cox & Parkin’s (1986) study of toddlers’ progression from rudimentary sketches to more developed forms like the tadpole, our study examines how inhibition and executive processes shape early children’s drawing abilities.

This study investigates whether motor skill development mediates the association between inhibition and drawing or if inhibition directly affects young children’s drawing abilities. We intend to investigate Simpson et al.’s (2017) Motor Development and Behavioural Inhibition hypotheses in children’s creative development. This research may increase executive function, child development, and early childhood sketching cognitive processes.

Current Study

Our study employs a methodological technique adopted from Silk and Thomas’s findings to test the claim that children’s level of inhibitory control affects their decision to draw a human or a dog (1986). The children who took part in our study ranged in age from 3½ to 5½, as older kids were in the range of our inhibition metric and smaller kids could not draw dogs. Our evaluation was centered on the children’s ability to control their innate desire to sketch a human and, as a result, their skill at drawing a dog, which was measured using a difference score. Determining how inhibitory control affects drawing abilities was the primary goal. Our hypothesis suggests a strong relationship between this difference score and their total inhibition rating, which is consistent with the principles of the Behavioural Inhibition theory, which maintains that inhibition significantly impacts young children’s capacity for creativity. As we explore the nuances of our approach and findings, we want to offer empirical insights into the relationship between children’s creative preferences and inhibitory control.

Hypothesis

There is no substantial difference in the inhibition requirements for children when drawing familiar objects like people compared to sketching novel subjects like dogs.

Methods

Participants

According to Silk & Thomas (1986), thirty children between the ages of three and a half and five and a half were randomly recruited from Colchester’s preschools and nurseries. These individuals’ demographic profiles showed an average age of 56.83 months with a standard deviation 7.543. The children came from a variety of social backgrounds, with the majority of them identifying as White. According to their teachers’ assessments, every participant was a fluent English speaker and did not indicate any behavioral or academic challenges.

Materials

For the drawing assignments, the study’s resources were pencils and plain A4 paper. A flip book with 20 pictures, four practice trials, and sixteen test trials was a part of the Day/Night challenge. Measuring 12 cm in height and 12 cm in width, each of the ten sun and ten moon representations made up the images. These materials offered a controlled and standardized platform for assessing cognitive processes in artistic expression to measure children’s inhibitory control throughout the drawing tasks and the Day/Night task.

Procedure

Three tasks were administered in a single session as part of the protocol and were counterbalanced in order. The youngster was given paper and pencil for the drawing jobs, which were laid on the table. In one task, they were to draw a picture of themselves and a picture of a dog in another. A summary of the two scales’ comprehensive scoring criteria provided enough details for replication. The introduction of the Day/Night activity, which was modified by Simpson et al. (2019), said that the participants were playing a lighthearted game. After that, they were given images of the sun and moon and told to name them orally. Participants were instructed not to name the photos; instead, they were to say “sun” to the picture of the moon and “moon” to the picture of the sun. After thoroughly explaining and demonstrating the rules for each picture, there were 16 test trials (ABBABAABBABAABAB) without any feedback after the first four practice trials (order ABAB) with feedback.

Strategy

This study uses a within-participants, correlational, experimental design that thoroughly explains the complex relationship between factors. Two critical factors were examined: the “inhibitory score,” determined during the Day/Night test, and the “drawing difference score,” computed as the dog score less the person’s score. The within-participants design makes it possible to evaluate individual differences in drawing skills across various subjects, and the correlational feature makes it easier to investigate possible relationships between drawing differences and inhibitory scores. This design decision provides a comprehensive understanding of the cognitive processes involved in children’s artistic expressions by allowing a detailed investigation of the relationship between inhibitory control and the ability to represent both familiar and unfamiliar things. The ensuing sections will expound upon the particular protocols and actions to clarify these connections.

Results

Table 1: Displays descriptive statistics of the variables involved in the study.

| Descriptive Statistics | |||||

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

| id | 30 | 22 | 93 | 56.90 | 21.796 |

| age | 30 | 42 | 65 | 56.83 | 7.543 |

| gender | 30 | 0 | 1 | .47 | .507 |

| dog | 30 | 0 | 9 | 4.83 | 2.291 |

| person | 30 | 3 | 5 | 4.60 | .621 |

| IC | 30 | 0 | 16 | 11.13 | 4.142 |

| differ | 30 | -5 | 4 | .27 | 2.050 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 30 | ||||

Table 2: Displays correlation analysis table between inhibition and difference score from SPSS.

| Correlations | |||

| IC | differ | ||

| IC | Pearson Correlation | 1 | .589** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .001 | ||

| N | 30 | 30 | |

| differ | Pearson Correlation | .589** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .001 | ||

| N | 30 | 30 | |

| **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). | |||

Descriptive statistics were utilized to provide a succinct overview of the data gathered, effectively capturing the subtleties of the research. For each condition—sketching a human figure (M = 4.60, SD = 0.621) and a canine figure (M = 4.83, SD = 2.291)—the mean and standard deviation were computed, as shown in Table 1. Furthermore, the average age of the participants was also found to be 56.83 months with a standard deviation of 7.543, based on a study with 30 participants. The average inhibition score for inhibitory control was 11.13 (SD = 4.142).

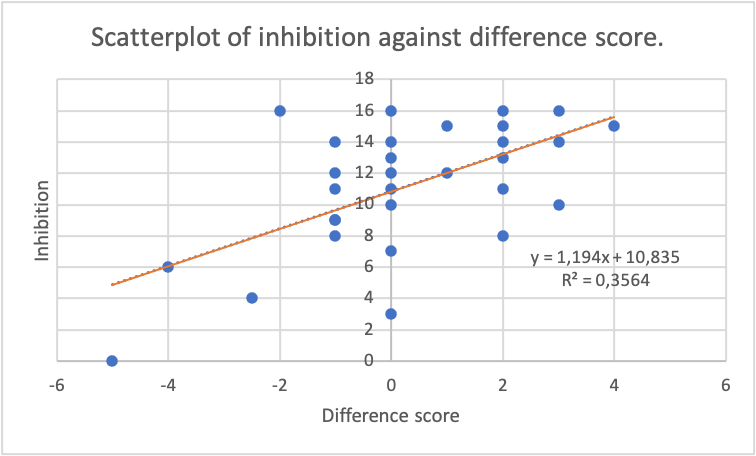

In inferential statistics, correlation analysis was utilized to determine the association between inhibition and the discrepancy score. The results show that inhibition and the discrepancy score have a link, with a Pearson coefficient of r(0.589) and a significance level of p(0.001), as shown in Table 2. The below Excel-generated scatterplot visually represents this interaction and highlights the complex relationship between inhibition and difference scores.

Figure 1: Scatterplot demonstrating the relationship between inhibition and difference score of children.

Discussion

Inhibitory control and the difference score showed a strong and statistically significant positive association, supported by the correlation analysis and shed light on the complex relationship between these variables. The Pearson correlation coefficient shows a significant relationship between the inhibitory control and the difference score. This is consistent with our initial theory, which states that children with higher inhibitory control also have more significant difference scores. The deficient significance level of p(0.001) emphasizes the dependability of this link. This significant result supports the idea that inhibitory control is essential in forming children’s drawing habits. Specifically, it prevents youngsters from sketching people when they would instead draw a dog. Further supporting the validity of our findings at the 0.01 significance level is the strong correlation between inhibitory control and the difference score, which is seen without repeated particular statistical data.

The “Behavioural Inhibition account” is supported by our study’s strong correlation, which supports the theory’s claim that inhibition prevents children from drawing a familiar human schema in favor of a novel subject, like a dog, allowing them to draw a wider variety of subjects. The relationship that our findings show emphasizes how important inhibitory control is to this adaptive sketching process. Notably, Simpson et al.’s (2019) study may have yet to show evidence in favor of the Behavioural Inhibition theory because it primarily examined familiar things like a person and a house. Simpson et al.’s (2019) work is still essential. However, our research indicates that inhibition’s impact on the development of drawing skills may still need to be fully understood, requiring more research in various settings to understand its effects on children’s cognitive development.

Limitation of study

Even though this study provided insightful information, a few limitations should be noted. First, the study’s primary focus on a particular age range may have limited the findings’ applicability to a broader population. Furthermore, the dependence on correlational analysis limits the ability to establish causation, highlighting the necessity of using experimental designs to distinguish between causal associations. Although the sample size is enough for statistical analysis, it might need to adequately represent the diversity of the population, which could affect the conclusions’ external validity. Moreover, focusing only on inhibitory control and sketching habits may miss other important aspects that play a role in children’s artistic development. Research with a more extended period would improve our comprehension of developmental paths. Finally, the study’s setting and cultural background should have been thoroughly investigated, suggesting that conclusions should be applied with caution to various cultural or environmental contexts. These drawbacks highlight the necessity for additional studies to tackle these issues and offer a more thorough comprehension of the intricate relationship between inhibition and kids’ sketching habits.

References

Baillargeon, R., Scott, R. M., & He, Z. (2010). False-belief understanding in infants. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14(3), 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.12.006

Cox, M. V., & Parkin, C. E. (1986). Young Children’s Human Figure Drawing: cross‐sectional and longitudinal studies. Educational Psychology, 6(4), 353–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144341860060405

Freeman, N. H., & Janikoun, R. (1972). Intellectual Realism in Children’s Drawings of a Familiar Object with Distinctive Features. Child Development, 43(3), 1116. https://doi.org/10.2307/1127668

Panesi, S., & Morra, S. (2016). Drawing a dog: The role of working memory and executive function. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 152, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2016.06.015

Panesi, S., & Morra, S. (2018). Relationships Between the Early Development of Drawing and Language: The Role of Executive Functions and Working Memory. The Open Psychology Journal , 11(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874350101811010015

Petersen, I. T., Hoyniak, C. P., McQuillan, M. E., Bates, J. E., & Staples, A. D. (2016). Measuring the development of inhibitory control: The challenge of heterotypic continuity. Developmental Review, pp. 40, 25–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2016.02.001

Siegler, R. S., Saffran, J., Gershoff, E., & Graham, S. (2017). How Children Develop (Canadian Edition). Macmillan Higher Education.

Silk, A. M. J., & Thomas, G. V. (1986). Development and differentiation in children’s figure drawings. British Journal of Psychology, 77(3), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1986.tb02206.x

Simpson, A., & Carroll, D. J. (2019). Understanding Early Inhibitory Development: Distinguishing Two Ways That Children Use Inhibitory Control. Child Development, 90(5), 1459–1473. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13283

Simpson, A., & Carroll, D. J. (2019). Understanding Early Inhibitory Development: Distinguishing Two Ways That Children Use Inhibitory Control. Child Development, 90(5), 1459–1473. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13283

Simpson, A., Al Ruwaili, R., Jolley, R., Leonard, H., Geeraert, N., & Riggs, K. J. (2017). Fine Motor Control Underlies the Association Between Response Inhibition and Drawing Skill in Early Development. Child Development, 90(3), 911–923. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12949

write

write