Abstract

The effect of animatics on recall and recognition rates was examined in this investigation. 47 psychology major students participated in the research in all. There were both live and nonliving words shown, some of which may be hazardous. The results showed that participants recalled live words more readily than lifeless terms. Threat-animated sentences were also used to enhance memory recall. It was simpler to understand words that had a feeling of motion than those that did not. The findings highlight the influence of emotional arousal on memory and are in line with other studies on the animacy effect. More research is required to understand the processes behind individual variations.

Introduction

Replication of memories is an essential cognitive process that keeps us operating on a regular basis. We may retrieve crucial information from memories, such as life-saving strategies, thanks to this intricate process. The “animacy effect,” or the distinctions between the recollection of animate and inanimate events, is, in fact, a fascinating phenomenon working, according to Meinhardt et al. (2019b). Animated items have features like life and motion, but lifeless objects don’t. Accessing information stored and encoded in the cognitive system is necessary for memory recall. There are several different ways to retrieve memories, including free recall, cued recall, and serial recall. In this inquiry, free recall will be our main focus. When no outside assistance is employed, information may be recovered by free recall.

By contrast, when we talk about memory retention, we imply the capacity to identify and remember previously stored information. This term pertains to determining whether a stimulus has been observed previously or not. Effective memory usage, and therefore good navigation and social interaction in the real world, depend on being able to recognize information that has been stored in one’s memory. People are more likely to recall live objects than nonliving ones, according to earlier studies. According to the literature, the preference for recalling alive items and their higher importance to survival may be explained by the increased processing and attention given to living things. Further enhancing memory encoding and retrieval is the emotional reactions to the activation of affective brain networks during exposure to animated stimuli.

There are numerous unanswered concerns despite the vast research on the animacy effect. It still needs to be clear if the amount of animacy, particularly depending on danger or emotion, has a role in issues like memory recall and recognition accuracy. This study fills that gap by methodically examining how animacy impacts memory and the potential mechanisms that underlie that effect. This study intends to investigate how the alive nature of words affects memory recall accuracy. We want to test if the animacy effect shown in previous research also holds true in our experiment. We also want to look at any potential short-term causes that may have contributed to this outcome.

Method

Participants

This study included 47 first-year undergraduate psychology students from two campuses (27 females, 18 males, and 2 non-binary) aged 17 to 33 (M = 20.11; SD = 4.06). Participants’ campus tutorial groups determined their memory or recognition state.

Materials

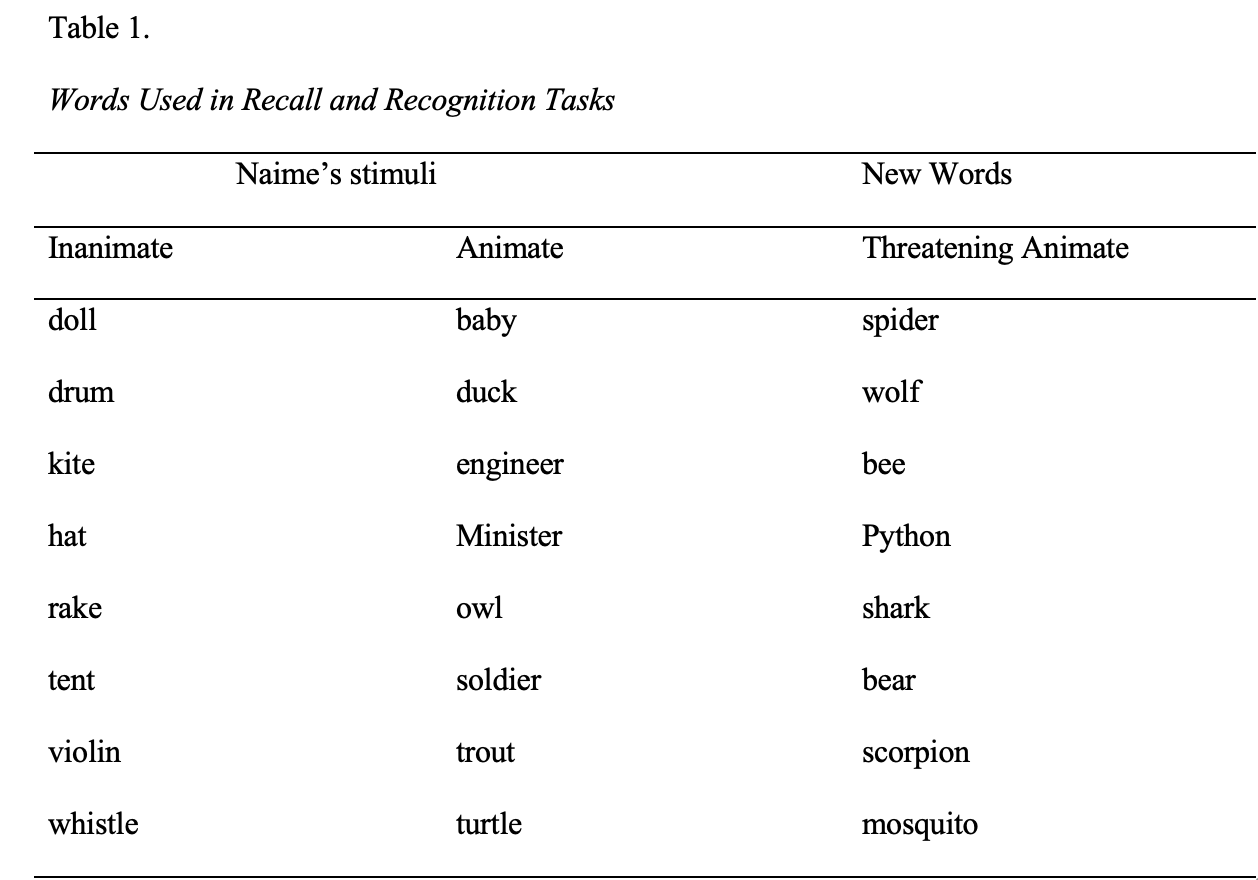

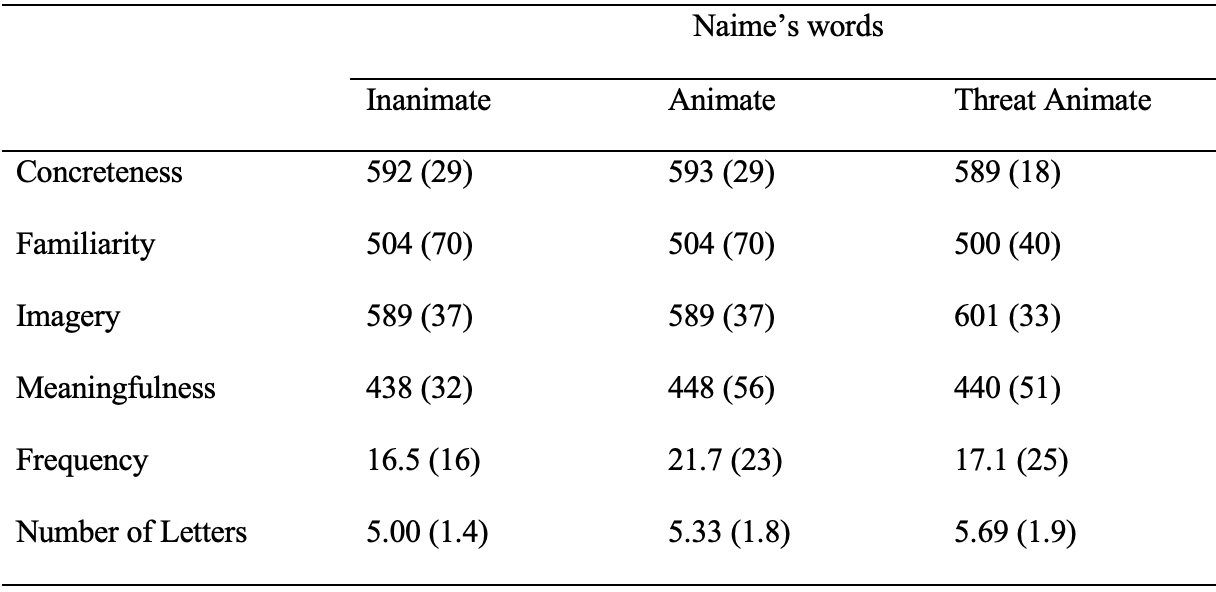

This study used living and inanimate terms. Table 1 shows the words. According to Table 2, animated, inanimate, and menacing words had the same concreteness, familiarity, imagery, meaningfulness, frequency, and quantity of letters.

Table 2

Means (standard deviations) on Various Dimensions for the Animate and Inanimate Words.

Procedure

Both conditions were presented on PowerPoint slides on the participants’ computer displays through video conference. During the study phase, participants read and memorized 28 words, shown one at a time for 5 seconds in all situations. An odd-even distractor task followed the final study list word in both cases. The distractor task participants marked each of the 20 single-digit numbers as odd or even on the online response page. Each number appeared for two seconds.

The free recall test required participants to recall study words and type their answers on the online recall response page. The recognition condition test participants received a sheet with 48 words (Nairne terms from Table 1 and random words) in random order. Participants were asked to select Nairne terms and random words from an internet list by clicking the corresponding check box.

Design

Both situations had animus and trial. Animacy includes animate, inanimate, and animate threat topics. Trial 1 and trial 2 are trial variables within a subject. Recall conditions depend on word recall accuracy. Recognition conditions depend on recognition accuracy.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the animate and inanimate words and additional threat animate words in the free recall condition are presented in Table 3. Comparisons between the three-word types in average recall and recognition accuracy were conducted using related samples t-tests.

Table 3

Descriptive Statistics and Animate and Inanimate Words Correctly Recalled for Each Trial.

| Word Type | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Average |

| Inanimate recall (n = 27) | 0.24 (0.10) | 0.40 (0.19) | 0.32 (0.15) |

| Animate recall (n = 27) | 0.31 (0.14) | 0.53 (0.16) | 0.42 (0.12) |

| Threat animates recall (n = 27) | 0.36 (0.20) | 0.59 (0.22) | 0.48 (0.20) |

In the Recall condition, related samples t-tests showed that, on average, animate and inanimate terms had different recall accuracy t (_26_) = _3.15___, p = _.001____. Animated words were better remembered. Threat living and inanimate terms had significantly different memory accuracy t (_26_) = 3.34, p = 0.008. Threat-animate words were better recalled than inanimate terms. Threat animates words had the same recall accuracy as animate words, t (26_) = _0.90___, p = _0.376___. Table 4 displays the accuracy score descriptive data for Nairne, animate and inanimate words, and extra threat animate word recognition scenarios.

Table 4

Descriptive Statistics and Animate and Inanimate Words are Correctly Recognised for Each Trial.

| Word Type | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Average |

| Inanimate recognition (n = 27) | 0.79 (0.10) | 0.82 (0.13) | 0.80 (0.10) |

| Animate recognition (n = 27) | 0.87 (0.19) | 0.93 (0.10) | 0.90 (0.13) |

| Threat Animate recognition (n = 27) | 0.92 (0.11) | 0.91 (0.11) | 0.92 (0.10) |

sssIn the Recognition condition, related samples t-tests showed that, on average, animate and inanimate words were recognized differently t (26__) = _4.81___, p = _.001____. Animated words were better recognized. Threat lives and inanimate terms were recognized t (26_) = 2.75, p =.001 differently. Threat-animate words were better recognized than inanimate terms. Threat animates, and animate words had the same recognition accuracy, t (26_) = __-0.35__, p = _0.728____.

Overall, individuals performed better for alive and threat animate terms than inanimate ones. Recognition accuracy was expected to be higher for animate words in general but not for threat animate words.

Discussion

The relationship between recall and recognition accuracy for animate and inanimate words was examined, as well as the effect of threat-animate words on memory performance. The findings provide insight into the animacy effect and memory processes. The memory of words with personalities and those without showed a significant difference. The finding that colorful descriptions were easier to recall than dull ones validated our theory. This is consistent with earlier research showing that individuals recall live things more vividly than inanimate objects (Rubin & Friendly, 1986). Our study has enhanced and established the significance of animacy in recall memory. terms connected to threats were easier to recall than inanimate terms. Information regarding prospective threats is simpler to remember. Leding (2018) asserts that emotionally salient stimuli, such as emotionally stimulating animate words, cause individuals to pay more attention to and properly remember information. This is supported by our results. Our findings suggest that strong emotions have an effect on memory.

The literature backs up what we found. Our findings support the commonly accepted hypothesis that while attempting to remember stimuli, we assign animated items more weight. The higher recall of threat-animate phrases is supported by prior studies on emotional arousal and memory performance (Nairne et al., 2013). We need to have looked into the precise mechanics of the current animacy effect. Threatening comments may increase emotional arousal, which in turn enhances memory recall. Future studies might examine the neural networks that control memory formation to determine how emotional and cognitive processes affect it. We must admit that not all facets of memory retrieval can be captured by our straightforward recall task, and that there may be gaps in our approach or other sources of inaccuracy that have an impact on our results.

In a nutshell, our research indicates that living words are easier for individuals to remember than lifeless ones. Words that suggested danger were easier to recall. These findings underline the significance of animacy and sentiments of enthusiasm in the study of memory. More research is required to fully understand the mechanics and develop this sector.

References

Leding, J. K. (2018). Adaptive memory: Animacy, threat, and attention in free recall. Memory & Cognition, 47(3), 383–394. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-018-0873-x

Meinhardt, M. J., Bell, R., Buchner, A., & Röer, J. P. (2019b). Adaptive memory: Is the animacy effect on memory due to richness of encoding? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 46(3). https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000733

Nairne, J. S., VanArsdall, J. E., Pandeirada, J. N. S., Cogdill, M., & LeBreton, J. M. (2013). Adaptive Memory: The Mnemonic Value of Animacy. Psychological Science, 24(10), 2099–2105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613480803

Rubin, D. C., & Friendly, M. (1986). Predicting which words get recalled: Measures of free recall, availability, goodness, emotionality, and pronunciability for 925 nouns. Memory & Cognition, 14(1), 79–94. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03209231

write

write