Being an Organisational Change Agent

Schein (2016) notes how culture is the main factor which effects organisational change management as it is a dynamic variable which influences all aspects of an organisation. Schein (2016) observes the symbiotic relationship of culture and leadership: an organisation can either ‘thrive or die’ depending on the proficiency of the manager. The importance of culture in influencing successful change explains the rationale for selecting Stroh’s (2015) 4 stage change process as a framework to collectively and successfully engage stakeholders in a process of organisational change (moving from a traditional office working environment to remote working during and after the coronavirus pandemic).

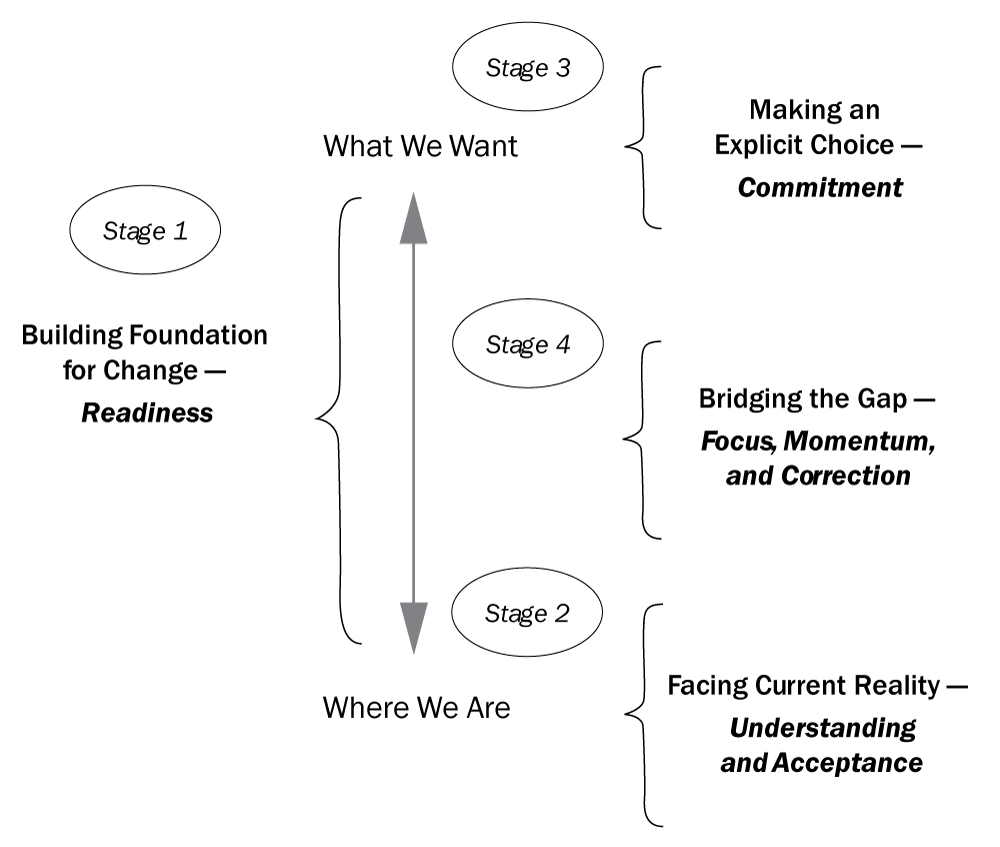

The model encompasses 4 non-linear, iterative stages, consulting with employees to achieve successful, systemic change:

(Stroh, 2015)

Stroh (2015) recommends that in the first stage of the model (building foundation for change) that key stakeholders are consulted for their ideas, beliefs and goals involving the change process and to cultivate a vision of what they would like to achieve from the change. Employees completed self-administered questionnaires to assess and quantify their attitudes and beliefs towards working at home and future aspirations regarding the issue. In order to accelerate change in this stage, Senge (2006) notes that managers can harness a sense of urgency from ‘creative tension’, which is the gap between the current reality and vision for the future. However, this assumes that all stakeholders possess a unanimous view of what their future goals and aspirations are. In this study, there was a spectrum of opinions and attitudes towards remote working garnered from the questionnaires with some employees enjoying the flexibility of working from home whilst others missed the workplace environment and struggled with isolation and depression. Stroh’s (2015) model is useful in assessing the readiness of employees to change and potential of developing a shared vision, though it can erroneously assume that all employees possess the same motivation for change. Nevertheless, the sample of this research study was relatively small, suggesting it is not unreasonable to assume that all employees would possess similar attitudes towards the change.

The goal of the second stage of Stroh’s (2015) model is to develop a deeper understanding of the current reality, forensically identifying stakeholders’ attitudes and motivations towards change. This was partially achieved through thematic coding of the self-administered questionnaires where key themes where identified. However, Hennick et al. (2020) note that responses from questionnaires can often be short and unsophisticated and prone to inaccuracy. Stroh (2015) advocates interviews as a data collection method of developing a deeper understanding of employees’ motivations but this was impracticable given the coronavirus restrictions. Stroh’s (2015) model of change can often be rigid and fails to acknowledge external factors (i.e. Covid-19 restrictions) and literature. To offset this, authoritative psychological theory informed the analysis of the results of this study. Coon and Mitterer (2015) purport that employees do not respond well to extrinsic incentives such as increased financial remuneration and better working conditions. Conversely, they surmise that employees are motivated more by intrinsic rewards like flexibility, fulfilment and autonomy. This was validated by the respondents in this study, who cited the advantages of working from home as better work-life balance, reduced stress and increased employee satisfaction. The disadvantages of working from home were also internal in nature: reduction in motivation, decreased mental health and missing the social aspect of the working environment.

The third stage of Stroh’s (2015) model involves stakeholders solidifying their commitment towards the organisational change and valuing the vision that the organisation has. Stroh (2015) recommends achieving this by educating them of the benefits of the change towards themselves and the organisation.

There was an aforementioned wide spectrum of attitudes exhibited by employees in the questionnaires towards remote working. Bass (1996) advocates displaying transformational leadership as a method of a leader inspiring their employees with a vision and encouraging and empowering them to achieve it. Odumeru and Ogbonba (2013) expound that transformational leadership can be a very powerful technique of engaging and aligning employees to achieve a common vision and increase their productivity and motivation.

Bass (1999) advocates that transformational leaders encourage employees to commit to an ideal for their vision of the future. Acknowledging the intrinsic nature of motivation could be potentially central to creating and co-ordinating a shared vision among employees over the future direction of the company’s working practices. Maslow (1970) notes in his hierarchy of needs that humans are ultimately driven by their desire to self-actualise and fulfil their potential. Encouraging employees to have a shared vision of self-actualising in this organisational change (regardless of whether they are removing working or not) could unite them in a common goal and make the process of change significantly easier. Stroh’s (2015) model provides a useful framework to conduct organisational change but is limited on practical advice in how to undertake that change.

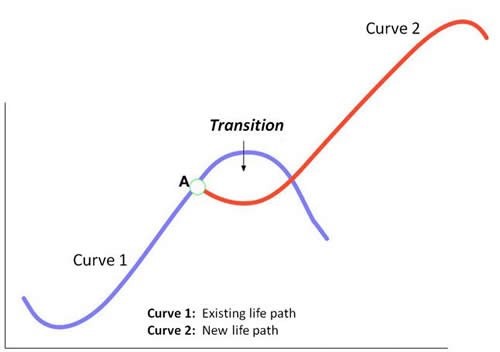

Stage 4 of Stroh’s (2015) deals with the practical aspects of change in ascertaining how to bridge the gap between their current reality and desired future vision. In relation to this research study, that concerns the optimum point to finalise working from home practices in the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic. Handy (1995) devised the Sigmoid Curve (also known as the ‘S’ curve), a graphical illustration of the periods of growth and decline that all businesses naturally iterate through. This has applications in organisational change management: Handy (1995) advocates making a new change prior to reaching the peak of an existing change (point A in the diagram):

Handy (1995) argues that pre-empting the change makes it more likely to be sustainable as a manager has the resources to forecast and prepare for the future change. This explains the rationale for conducting this research study and correctly timing the shift in working practices by planning in advance of what that change may entail by assessing employees’ opinions and attitudes towards remote working.

Ultimately, Stroh’s (2015) model provided a useful framework for organisational change, though it needs to be aided significantly practically by eminent theory and literature.

Conflict and Negotiations in Change and Organisational Improvement

Change management in organisations can often initiate conflict and disputes. The changes in working environment due to the coronavirus pandemic and consequent increase in the amount of conflicts necessitated that I studied several sophisticated methods of conflict resolution and negotiation to use in my practice.

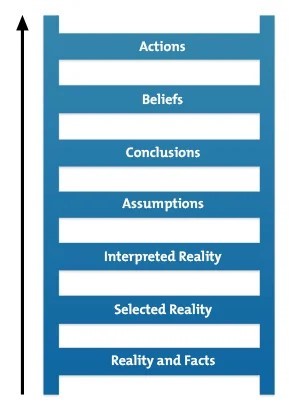

Argyris (1982) developed an authoritative model called ‘the ladder of inference’, which describes the cognitive biases individuals can suffer from in conflict. Argyris (1982; 1990) postulated in his model that there are a number of rungs on the ladder (subconscious processes) individuals progress through in order to reach a fact from a decision or action:

(Argyris, 1990)

Argyris (1990) observes that people’s beliefs often heavily influence their reality, often reaching an opinion in a conflict without due consideration or reflection. To remedy this, he advocates using the ladder of inference to come to a more informed conclusion. Argyris (1982) articulates that individuals achieve this by firstly identifying which stage (rung) of the thinking process they’re currently at. Consequently, he advises them to restart the ladder of inference, reascending it to gain a more realistic view of the situation through a logical, step-by-step process.

This proved to be a useful model to resolve conflicts about remote working in my practice. It allowed me to remain mostly detached from the situation and the emotional milieu that encompassed certain situations and issues. Engleman et al. (2009) caution of ‘expert bias’, where those in leadership and managerial positions assume their stance is correct due to the authority they have. Using the ladder of inference to resolve conflicts negated that bias and assured that I was able to consider other employees’ opinions better.

Nevertheless, there were some circumstances where it was very difficult and impractical to implement this model. Shields (2021) notes that the coronavirus pandemic instigated more frequent disputes between managers and their employees due to decreased morale and increased emotional pressures caused by communication difficulties in hybrid working environments due to lockdown. Occasionally, the emotional toll of lockdown and logistical problems made it difficult to remain objective which is essential to the ladder of inference to be effective. However, implementing the ladder of inference increased my emotional quotient/intelligence (Goldman, 1998) and ability to delay gratification and practice self-control in order to remain objective, which are essential qualities for a manager to successfully resolve conflict (Seijts, 2013).

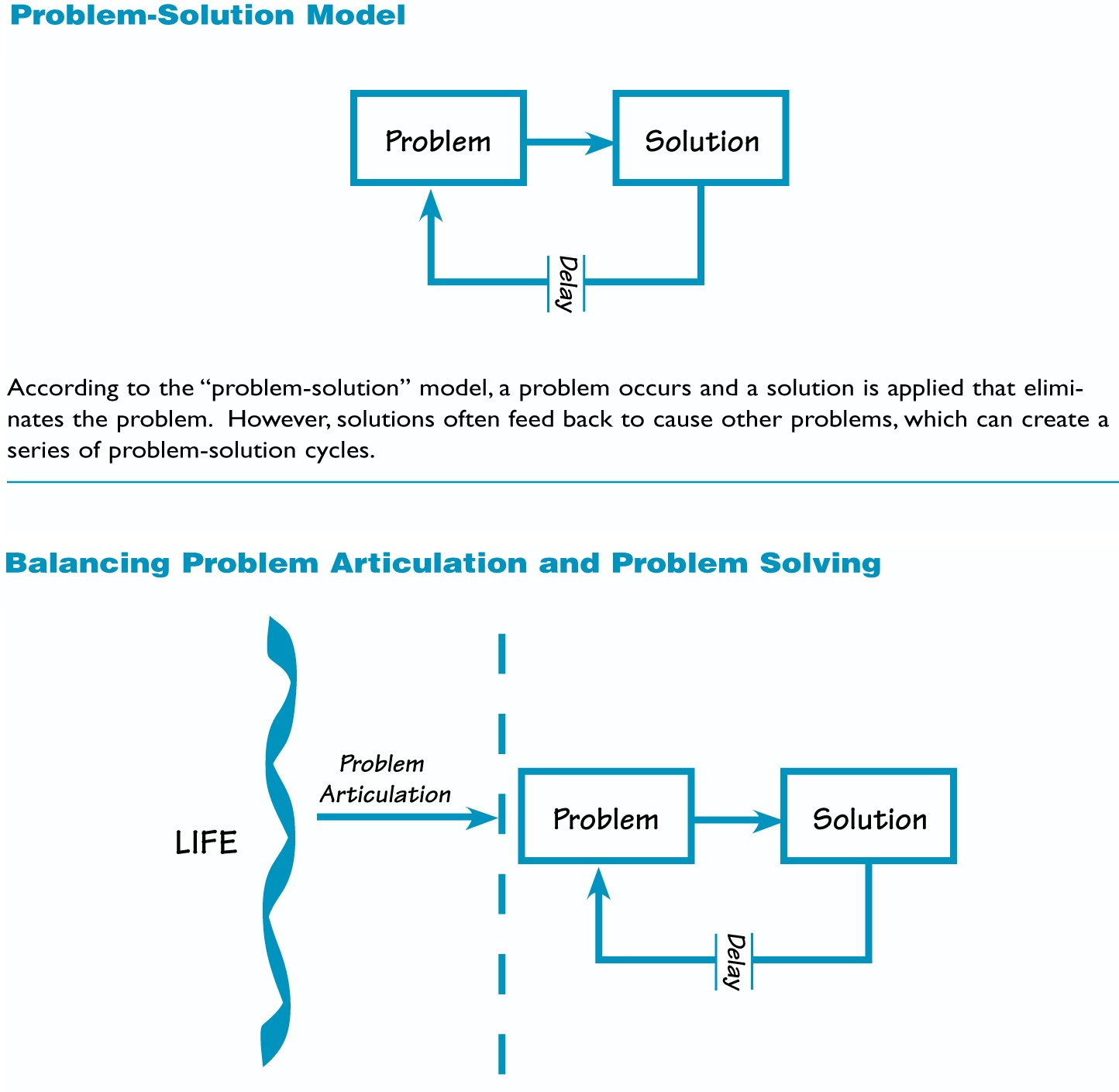

Kim (2018) makes reference to the ladder of inference in his method of conflict resolution, arguing that the majority of individuals are trapped in a reflexive loop of finding problems and solutions, hindered by their own unhelpful thinking styles and biases. Kim (2018) elaborates that finding solutions often promulgates more problems, perpetuating the vicious cycle.

(Kim, 2018)

In order to escape the continual problem-solution structure, Kim (2018) recommends studying problem articulation and re-examining how we think about matters, inferring that whether we view an event or solution as a problem depends on our view of the world:

Studying this process was enlightening as it enabled me to realise that matters that had previously caused conflict (difficulties in communicating with employees and disrupted working practices) were partially because I viewed them as problems. Kim (2018) astutely observes that a significant proportion of problems are only valid because individuals view them that way. Recognising this allowed me to resolve conflict more effectively as I no longer viewed certain situations as problems, instead using them as opportunities for advancement, displaying a growth mindset (Dweck, 2006). However, Kim’s (2018) model is somewhat idealistic and fails to acknowledge the difficulties of adopting such a stance. In some cases, it even caused more conflict and stress due to employees struggling to adopt this perspective in a period where they were already suffering significant emotional distress.

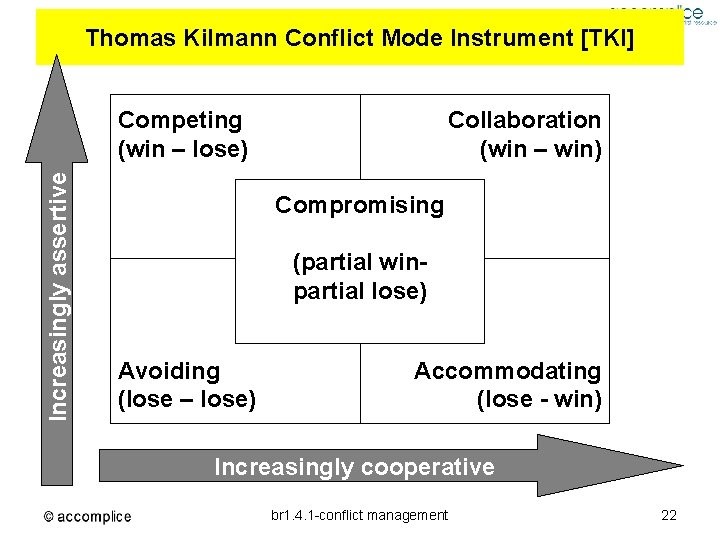

Thomas and Killman (1978) conceptualised a model of conflict which helps a manager/leader to decide on the appropriate course of action to resolve conflict. It identifies two variables which influence the strategy adopted: assertiveness (the degree which you attempt to satisfy your own needs) and cooperativeness (how much an individual aims to appreciate the other person’s concerns) which are illustrated in the matrix below:

(Thomas and Kilmann, 1978)

Using this model to handle conflict was useful in a myriad of ways. Firstly, it allowed me to prepare and co-ordinate my strategy in order to resolve conflict effectively depending on the situation and personality of the individual involved. The flexibility of the model was also useful as it enabled me to institute a range of strategies to resolve conflict as the situation required. Finally, it allowed me to exhibit some control in a challenging situation by working towards methods of handling conflict where both parties benefitted (compromising and challenging). However, a weakness in this approach is that it neglects the influence and importance of the role of the employee, being management-centric (Altmäe et al., 2013) In some cases, the employee was un-cooperative, making it exceptionally difficult to progress to the desired modes of handling conflict of compromising and collaborating where both parties mutually benefit. Nevertheless, using this approach allowed me to pre-empt conflict and plan how I was going to manage it, a preventative approach which deals with conflict effectively and efficiently (CIPD, 2020).

The models of conflict resolution and negotiation covered in this assignment have significantly enhanced my practice and bolstered my skills in these areas. I plan to evidence these skills in my portfolio through anonymised records of meetings/appointments to resolve conflict and progress made towards meeting agreed targets in such meetings. To further illustrate these skills, levels of employee satisfaction concerning the changes in working practices will be comprehensively illustrated through qualitative and quantitative data, a thorough and reliable method of data collection (Johnson et al., 2007).

In summary, the conflict resolution and negotiation models can provide useful structures/frameworks to resolve conflict though their nuances are not always enacted in practice, particularly due to the challenging circumstances of the coronavirus pandemic. However, a reasonable supposition could be made that, as lockdown restrictions ease and normality returns, these models of resolving conflict may have greater relevance and effect in my practice.

References

Altmäe, S., Türk, K. and Toomet, O. (2013) ‘Thomas-Kilmann’s Conflict Management Modes and their relationship to Fiedler’s Leadership Styles (basing on Estonian organizations).’ Baltic Journal of Management. 8 (10).

Argryis, C. (1982) ‘The executive mind and double-loop learning.’ Organizational dynamics, 11(2), 5-22.

Argryis, C. (1990) Overcoming Organizational Defenses: Facilitating Organizational Learning. Allyn & Bacon, Needham.

Bass, B. M. (1990) ‘From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision’. Organizational Dynamics. 18 (3): 19–31.

Bass, B.M. (1996) A new paradigm of leadership: An inquiry into transformational leadership. Alexandria, VA: US Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences.

Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (2020) Managing Conflict in the Modern Workplace. (Online). Available at: https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/fundamentals/relations/disputes/managing-workplace-conflict-report (Accessed: 21 November 2021).

Coon, D. and Mitterer, J. (2015) Introduction to Psychology: gateways to mind and behaviour. 14th ed. New York: Cengage Learning.

Dweck, C. S. (2006) Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Random House.

Engleman, J. B., Capra, C. M., Noussair, C. and Berns, G. S. (2009) ‘Expert Financial Advice Neurobiologically ‘Offloads’ Financial Decision Making Under Risk’, PLOS ONE 4 (3): 49-57.

Goleman D (1998) ‘What Makes a Leader?’. Harvard Business Review, 76: 92–105.

Handy, C. (1995) The Empty Raincoat: Making sense of the future. London: Arrow Books.

Hennink, M., Hutter, I. and Bailey, A. (2020) Qualitative research methods. London: Sage.

Johnson, R.B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J. And Turner, L. A. (2007) ‘Towards a definition of Mixed Methods Research.’ Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1:112.

Kim, D. (2018) Paradigm-Creating Loops: How Perceptions Create Reality. (Online). Available at: https://thesystemsthinker.com/paradigm-creating-loops-how-perceptions-shape-reality/ (Accessed: 19 November 2021).

Maslow, A. H. (1970) Motivation and personality. New York: Harper & Row.

Odumeru, J. A and Ogbonna, I. G. (2013) ‘Transformational vs. Transactional leadership theories: Evidence in literature.’ International Review of Management and Business Research, 2(2), 355.

Schein, E. (2016) Organisational Culture and Leadership. 5th edn. New York: Wiley.

Seijts, G. (2013) Good Leaders Learn: Lessons from Lifetimes of Leadership. New York: Routledge.

Senge, P. M. (2006) The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Doubleday.

Shields, A. (2021) The impact of COVID on Workplace Conflict. (Online). Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/annashields/2021/07/28/the-impact-of-covid-on-workplace-conflict/?sh=e134d227ccba (Accessed: 19 November 2021).

Stroh, D. P. (2015) Systems thinking for social change: a practical guide to solving complex problems, avoiding unintended consequences, and achieving lasting results. New York: Chelsea Green.

Thomas, K. and Kilmann, R. H. (1978) ‘Comparison of Four Instruments Measuring Conflict Behavior.’ Psychological Reports, 42 (3): 1139–1145.

write

write