Educational Theory and Policy

The educational attainment of looked after children and young people (LACYP) in Wales is significantly below average: Mannay et al. (2017) report that in 2015, 18% of LACYP achieved 5 GCSEs grade A*-C compared to 58% of students who hadn’t been in care. Mannay et al. (2017) outline educational measures taken to address this attainment gap including educational co-ordinators to monitor progress, catch-up support and LACYP specific subject teachers under legislation such as The Children and Young Person’s Act (2008) and The Social Services Well-Being Act (2014). Mannay et al. (2017) focus singularly on educational interventions to improve attainment whereas Jones et al. (2011) recognise the impact of iniatives outside the classroom:

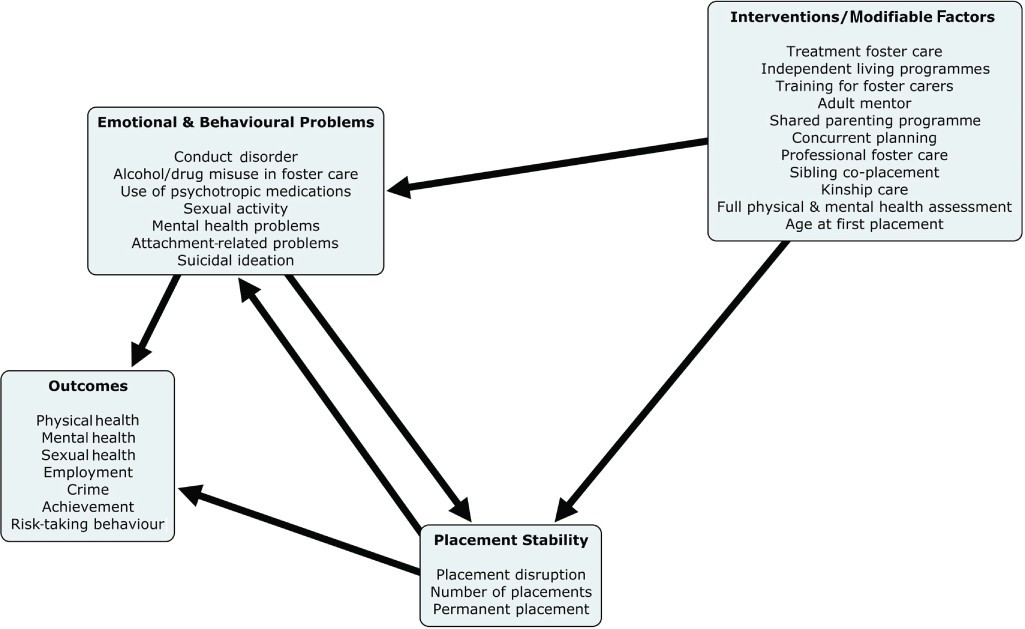

(Jones et al., 2011)

Mannay et al. (2017) cite a range of factors which explain this low attainment including deprivation, childhood trauma and breakdown in family relationships. Jones et al. (2011) concur, identifying emotional and financial neglect from parents as the main reason children enter care. Stein (2012) notes that the majority of children enter care between 13 to 15 years old, again illustrating the complexity of factors governing low attainment in LACYP. O’Higgins et al. (2017) surmise that there is a more underlying cause for this attainment gap, which numerous government interventions seem to have failed to address.

Stigma and educational barriers for LACYP

Mannay et al. (2017) theorise that cultural factors in stigma and labelling of LACYP pupils are key factors in low attainment. This seems to be validated in both theory and practice. Jackson and Cameron (2014) note that teachers seemed to have lower expectations of LACYP, not expecting them to progress to higher education. This was experienced by one of the participants in the study (“my sixth form leader told me that I will have no chance of getting into university so I thought I will show her I can get there”). However, this stigmatisation does not seem to affect pupils’ career plans: Mannay et al. (2017) note that the LACYP consulted in the study articulated career aspirations similar to non-LACYP pupils, including professional occupations such as doctors, vets and architects. Their background often motivated them: (“it’s all about motivation, right that’s it I want to do something with my life.”).

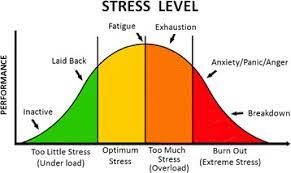

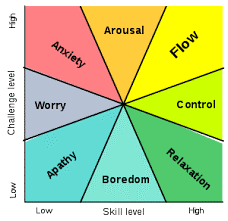

However, the effects of being labelled ‘looked after’ seemed to damage some pupils’ confidence, causing them to view their identity pejoratively (“You don’t want to be looked after, you want to be a normal kid”, “I hate people feeling pity for me, I’m just a normal child, even if I’m in foster care”). Mannay et al. (2017) observe that labouring against a backdrop of low expectations can make it especially difficult for LACYP to succeed academically. However, this article neglects the point that motivation and attitude are also important determinants of academic attainment. Coon and Mitterer (2015) note that an individual performs better when they are intrinsically driven (self-motivated) whilst Dweck (2006) eruditely states that an individual who displays a growth mindset (seeing problems as opportunities) will also perform well. Nevertheless, Berridge et al. (2004) surmise that the emotional toll LACYP pupils face negatively impacts attainment, which is reiterated by authoritative psychological theories on arousal:

(Yerkes and Dodson, 1908)

(Csikszentmihalyi, 1990)

Data Collection

Mannay et al. (2017) consulted 67 LACYP from Wales to inform the study, ranging from 6-27 years old. Greig et al. (2013) advise that this is an appropriate sample size for a research study of this magnitude, from which relevant conclusions can be drawn from though Haeussler et al. (2013) note that a smaller sample size can be more expedient to analyse and draw conclusions from. However, the gender composition of the study was not completely representative of the LACYP population of Wales: participants were in a 60-40 male-female ratio which differs from 46% of girls and 54% of boys in public care in Wales (Welsh Government, 2015). The participants were drawn from a wide cross-section of educational levels, ranging from primary schools to further education. Cohen et al. (2017) advocate this strategy of including pupils from numerous phases of education, arguing that this wide coverage can give a greater breadth of perspectives to research and increase its validity, though participants were not selected systematically.

Mannay et al. (2017) collected information qualitatively through semi-structured in-person and telephone interviews and focus groups conducted by peer-researchers who had experience of being in care, before interview data was transcribed and analysed thematically. Byrne et al. (2015) advocate this form of data collection, observing that it results in more honest and authentic responses from interviewees as they feel less intimidated by the interviewer’s more informal style. This seems to be validated by the amount of anecdotal information volunteered by participants. Byrne et al. (2015) note this style of this interviewing is especially appropriate for sensitive issues such as educational experiences of those in care in this study. However, Johnson et al. (2007) observe that this relies solely on qualitative information, arguing that it is subjective and not necessarily generalisable to the rest of the population. Instead, they recommend using a mixed methods paradigm, collecting qualitative and quantitative information to ensure rigour and reliability.

Conclusions and educational implications of a research article

Mannay et al. (2017) note that there needs to be a change in how LAYCP are perceived in education as such attitudes can be limiting and damaging to their aspirations (Jones et al , 2011). Mannay et al. (2017) assert that teachers should encourage pupils to realise their potential, irrespective of their background. This could have positive applications in improving attainment, as Mannay et al. (2017) elaborate that the majority of LACYP participants in their study were highly motivated. However, the methods of increasing attainment in LACYP are more nuanced than those covered in this article: Gardner (2006) advocates a highly individualised style of teaching which caters for all learning styles to foster engagement and progression. Sager (2013) lectures on the importance of the ‘hidden curriculum’ in increasing attainment, where teachers model the habits and attitudes they wish pupils to display. These methods take into account the emotional aspect of educating LACYP pupils.

It’s difficult to generalise the results of this study given it is an area which limited empirical research has been conducted into (Mannay et al., 2015), though the study is given added credibility by being one of the first to investigate this subject matter empirically. Further studies will be need to be undertaken to validate and build on the findings of this research, collecting quantitative data and comparing this with data on non-looked after children for increased validity and reliability.

References

Berridge, D., Dobel-Oder, D., Harker, R. and Sinclair, R. (2004) Taking Care of Education: An evaluation of looked-after children. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Byrne, E., Brugha, R. Clarke, E., Lavelle, A. and McGarvey, A. (2015) ‘Peer Interviewing in qualitative interpretive studies: An art in collecting culturally sensitive data?.’ BMC Research Notes.

Cohen, L., Manion, L and Morrison, K. (2017) Research Methods in Education. London: Routledge.

Coon, D. and Mitterer, J. (2015) Introduction to Psychology: gateways to mind and behaviour. 14th edn. New York: Cengage Learning.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990) Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row.

Dweck, C. S. (2006) Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Random House.

Gardner, H. (2006) Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons in Theory and Practice. New York: Basic Books.

Greig, A., Taylor. J. and MacKay, T. (2013) Doing research with children: a practical guide. London: Sage.

Haeussler, E., Paul, R. and Wood, R. (2013) Introductory Mathematical Analysis for Business, Economics, and the Life and the Social Sciences. 13th Edn. London: Pearson.

Jackson, S. and Cameron, C. (Eds) (2014) Improving access to further and higher education for young people in care: European Policy and Practice. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Johnson, R.B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J. and Turner, L. A. (2007) ‘Towards a definition of Mixed Methods Research.’ Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1:112.

Jones, R., Everson-Hock, E.S., Papaioannou, D., Guillaume, L., Goyder, E., Chilcott, J., Cooke, J., Payne, N., Duenas, A., Sheppard, L.M. and Swann, C. (2011) ‘Factors associated with outcomes for looked-after children and young people: a correlates review of the literature.’ Child: Care, Health and Development, 37, pp. 613-622.

Mannay, D., and Staples, E., Hallett, S., Roberts, L., Rees, A., Evans, R. and Andrews, D. (2015) Understanding the educational experiences and opinions, attainment, achievement and aspirations of looked after children in Wales.

Mannay, D., Evans, R., Staples, E., Hallett, S., Roberts, L., Rees, A. and Andrews, D. (2017) ‘The consequences of being labelled looked-after: Exploring the educational experiences of looked-after children and young people in Wales’, British Educational Research Journal, 43 (4), pp. 683–699.

O’Higgins, A., Sebba, J. And Gardner, F. (2017) ‘What are the factors associated with educational achievement for children in kinship or foster care: A systematic review,’ Children and Youth Services Review, Elsevier, 79(C), pp. 198-220.

Sager, M. (2013) ‘Understanding the Hidden Curriculum: Connecting Teachers to Themselves, Their Students, and the Earth’ Leadership for Sustainability Education Comprehensive Papers. Paper 7.

Stein, M. (2012) Young people leaving care: supporting pathways to Adulthood. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Welsh Government (2015) Children looked after at 31 March by local authority, gender and age. [Online]. Available at: statswales.wales.gov.uk/Catalogue/Health‐and‐Social‐Care/Social‐Services/Childrens‐Services/Children‐Looked‐After (Accessed: 17th November 2021).

Yerkes, R. M. and Dodson, J. D. (1908) ‘The relationship of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit formation.’ Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18, 459–482.

write

write