Abstract

This study aimed to examine students’ perception of the effectiveness of professor ratings on their academic outcomes in a higher-learning institution setting. Specifically, this report analyzed the impact of a professor’s teaching style and teaching effectiveness, grading policies, availability and accessibility for consultation, course content and structure, and other subjective factors that impact students’ academic performance. The report used a mixed-methods approach combining quantitative data from a questionnaire with a systematic literature review technique to identify student perceptions of the effectiveness of professor ratings in impacting academic outcomes. The study cross-examined a set of 15 peer-reviewed journal articles that revealed key themes on confounding factors such as bias against female teachers, classroom characteristics, and the diverse perceived importance of SETs evaluation criteria among students that affect the learner’s perspective of the significance of professor ratings on affecting the quality of higher education. The report also utilized a structured questionnaire to collect primary data from 30 respondents (n=30) currently enrolled in an American University and those who have completed at least one semester using a convenient sampling technique. The statistical results showed that most higher education students rarely or sometimes used SETs to make course selection decisions. A non-parametric Chi-square test facilitated the rejection of the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative view stating that higher education learners believe SET survey ratings have a significant impact on their academic success and thus are willing to make critical course selection decisions and recommendations based on information gained from these student evaluations of teachers survey. The findings presented in this report can inform students in higher learning institutions about the reliability and validity of SET surveys to better make lifelong decisions, such as which course to pursue at the University.

1.0 Introduction: Background of Study

Higher education stakeholders, including policymakers, university department heads, and students, use professor ratings to make course selection and academic performance improvement decisions. While these stakeholders understand the importance of these professor performance metrics in making educational decisions, they highly question their effectiveness in improving the quality of higher education. In brief, professor rating systems, also known as student evaluations of teaching surveys (SETs), are tools higher education institutions use to allow learners to give feedback about their experiences with their professors (Lohman, L., 2021, 3). These systems help higher education students to evaluate the quality of instruction they receive through a coordinated feedback loop that learning institutions can use to identify areas for improvement. According to Lohman, L. (2021), professor rating systems are anonymous survey forms that instructors administer to their students at the end of a course. The anonymous surveys require students to give feedback on key learning areas such as the instructor’s teaching style, knowledge of the subject matter, communication skills, accessibility, availability for consultation, and fairness in the grading process. Universities have adopted these new tools to replace the traditional word-of-mouth recommendations about course selection that students used to get from academic advisors, peers, career mentors, and other public online platforms. While these new tools have been hailed as helpful in assessing learner feedback regarding their higher education experiences, their effectiveness in determining a learner’s perceived academic performance still needs to be determined.

This report seeks to examine the students’ perception of the effectiveness of professor rating surveys (or SETs) in improving the learning outcomes of higher education students. The report will use qualitative and quantitative techniques to analyze the relationship between students’ perceptions of professor rating systems and academic performance. The study’s findings provide helpful insight to university human resource managers, higher education policymakers, and learners on using student evaluation of teaching surveys (SETs) to improve institution-wide academic success. Policymakers can also use the findings of this study to inform their professor’s hiring, retention, and promotion decisions. Finally, students can use the results to make better decisions during the course selection process for better academic outcomes.

1.1: Objective of Study

In higher learning institutions, student evaluations of teaching or professor ratings serve as an essential metric for assessing the quality of instruction that educators provide to their students. Students use these ratings to evaluate the professor’s teaching approach and determine their effectiveness before making lifelong course selection decisions. On the other hand, universities use the SETs to evaluate the instructors’ performance, from which they make critical retention and promotion decisions. While many higher learning institutions have made professor ratings a common practice, contemporary research needs to research how students perceive these ratings and their impact on academic outcomes. This study seeks to bridge this gap in the literature by using mixed methods to interrogate the qualitative and empirical evidence of students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of professor rating systems to improve the quality of higher education and inform lifelong decisions such as course selection.

2.0: Chapter Two: Literature Review

2.1: Literature Review Background and Conceptual Model

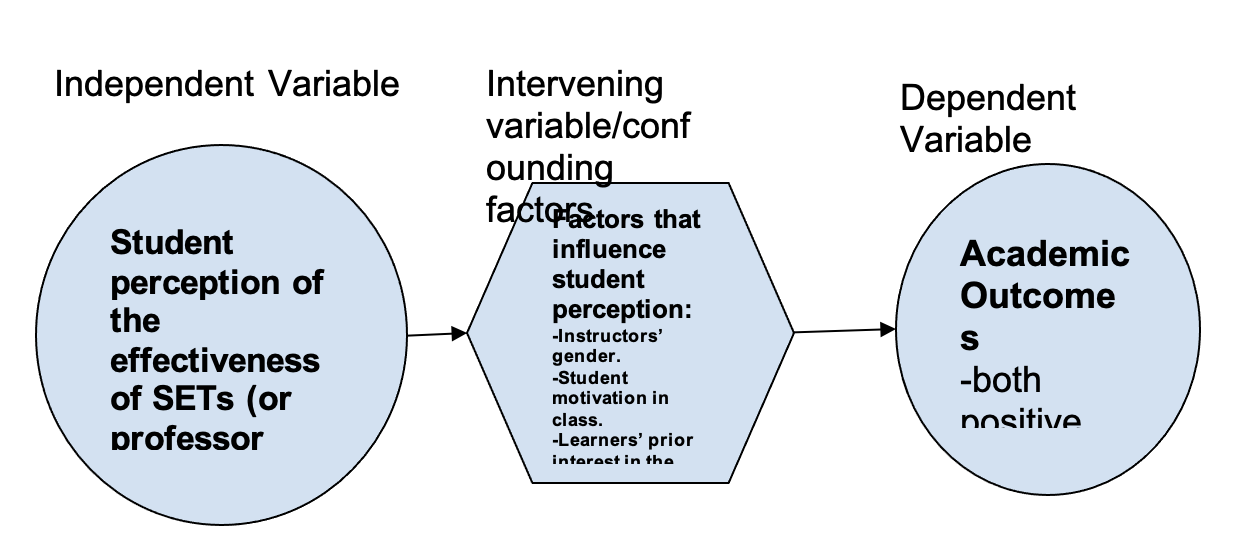

This report section reviews the existing literature based on four critical emergent themes from previously conducted studies. These themes include student bias in reviewing their professors, expert concern about the reliability and validity of SETs, student perspectives about the effectiveness and importance of professor ratings, and the factors affecting students’ rating behaviors. This study is based on the premise that the independent variable, student perception of the effectiveness of SETs, influences the dependent variable, academic outcomes/performance, with critical co-founding factors that play a significant role in moderating the relationship between these core variables. The conceptual model below summarizes this relationship as presented in the existing literature.

Figure 1.0: Conceptual Model Showing the Relationship Between Key Study Variables

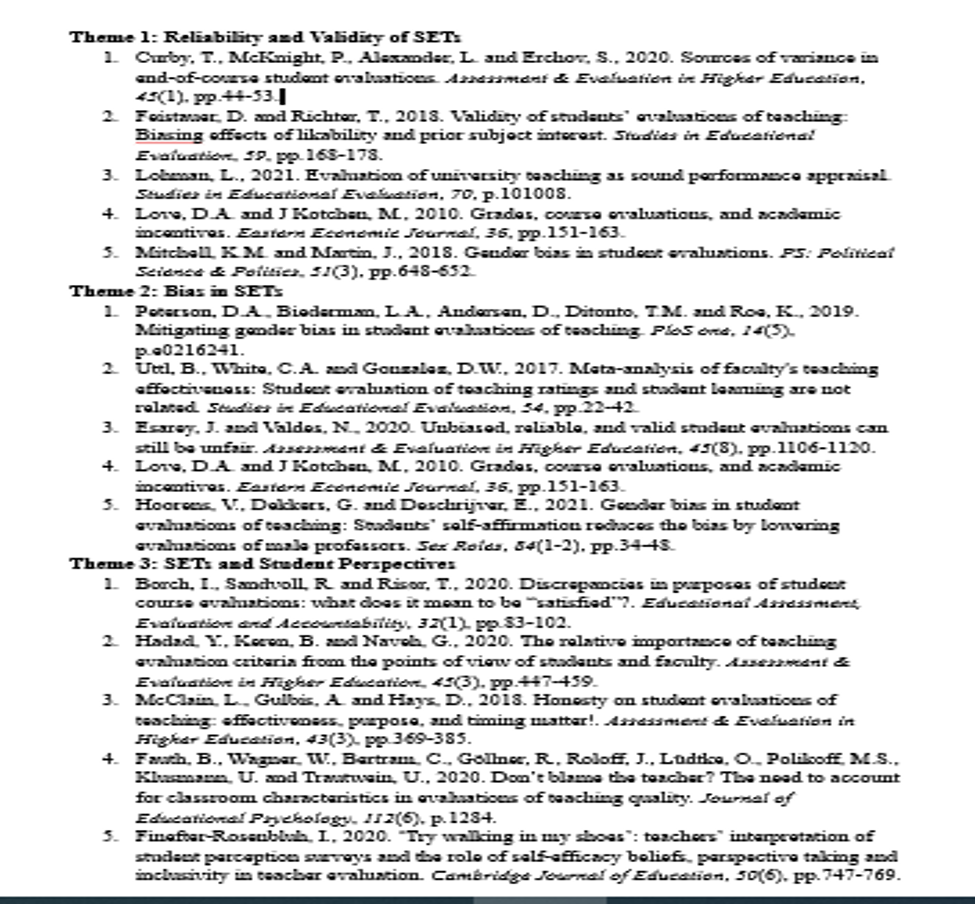

This report acknowledges that the relationship between student perception of the effectiveness of SETs and academic performance is not a simple direct correlation but a rather complex association with multiple mediating factors. This comprehensive literature review section presents the existing evidence linking student perception of the effectiveness of SETs and learner academic outcomes in higher learning institutions. This section focuses on themes that fall under these intervening variables, also called confounding factors, in this report. The Table matrix below summarizes the critical literature reviewed in this section categorized under three core themes of SETs bias, reliability and validity, and overall student perception about professor rating systems.

Figure 2.0: Thematic Literature Review Matrix of Existing Evidence on Study Variables

This report synthesizes these literature works into a comprehensive, objective analysis of existing evidence to inform the fundamental arguments of this study. The factors affecting students’ ratings of their professor were not categorized as a critical theme examining student perspective and perception because they are a unique set of forces that impact learner attitude and rating behaviors towards individual professors instead of expressing an objective assessment of teaching effectiveness. Nevertheless, these factors affecting students’ rating behavior and patterns in rating individual professors play a critical role in determining how learner perception influences academic outcomes directly or indirectly. This literature review section will review these factors alongside the three key themes identified in the literature matrix above to understand better how students’ perceptions of professor rating surveys impact the overall academic performance of higher education learners.

2.1: Factors Affecting Student’s Rating of Their Professor

Current literature identifies five key factors that affect student ratings of their professors. These critical factors include the teaching style and effectiveness, grading policies, professor’s accessibility and availability, course content and structure, and other subjective personal factors. Teaching style refers to how a professor teaches, their choice of course materials, their ability to explain concepts to learners clearly, and their ability to keep the students engaged—all influence how students perceive the effectiveness of instructor rating systems and practices. Grading policies also influence students’ perception of fairness and consistency with the institution’s grading system and, thus, their overall satisfaction with a professor. Professors with clear grading policies and clear expectations are most popular among students. The instructor’s accessibility and availability impact learners’ sense of engagement. Professors who are approachable and responsive to emails and those that are readily available during office hours for consultation sessions with students receive favorable ratings from students. Learners feel more supported and encouraged when their instructors are accessible and willing to provide guidance.

The course content and structure can also impact the learner’s learning experience either negatively or positively. The course workload, relevance and applicability of the course material, and difficulty level all impact how students feel about their professor and, thus, the ratings they assign to these professional educators. Students tend to view professors who challenge them while providing support and resources more positively and thus equally rate them well. Finally, personal factors also play a pivotal role in determining how negatively or positively students rank their educators. Diverse learners’ personal biases and experiences play a significant role in shaping how they perceive their professors. Age, race, and gender impact students’ perception of their professor. The diverse personal background and experiences also shape how learners see and perceive their university educators. It is important to note that professor ratings and evaluations should be based on objective measures of a professor’s performance rather than subjective biases based on personal emotional experiences.

2.2: Theme #1: Bias, Reliability, and Validity of SETs/Professor Rating Surveys

Student evaluation of teachers, commonly referred to as ‘professor rating surveys’ or ‘teacher ranking systems,’ have become mainstream tools that policymakers, more so human resource managers in higher learning institutions, use to make hiring, retention, and promotion decisions that help stakeholders, including students, realize improved academic performance. This critical role that SETs play in determining the quality of higher education begs the question of their validity and reliability. Researchers in the past, such as Lohman L. (2021, 151), have conducted studies seeking to examine the reliability and validity of these professor-rating surveys. In her article evaluating the soundness of SET as a proper performance appraisal method for professors, she argues that stakeholders should view SETs through the lens of performance appraisal principles established in human resources literature as opposed to viewing it through the lens of student ratings of their educators. Lohman’s article thus focuses on bridging the gap in the current literature by clarifying how assessment of a professor’s teaching effectiveness can be done under the principles of performance appraisal by deploying SET and peer review of teaching within a larger framework of recommended human resources practices.

Lohman’s is one of the few peer-reviewed journals seeking to examine the problem of bias associated with SETs results. The author used a systematic literature review methodology to review recent literature on SET related to the performance appraisal principles of performance-based management. Policymakers in higher education use these principles to optimize their human resource policies and procedures while still clarifying the weaknesses of traditional and recently revised approaches to teaching evaluation.

Lohman’s (2021) article makes several valuable contributions to the existing literature on student evaluations for sustainable, improved academic performance. The article highlights bias as one of the most significant risks associated with viewing teaching evaluation solely through the lens of SET. Secondly, Lohman L. (2021) emphasizes the importance of deploying SET and peer review of teaching within a larger framework of established human resources techniques to ensure consistent and reliable evaluation of teaching performance (154). The article then provides practical recommendations for conducting SETs as lawful, reasonable, and financially sound performance appraisal techniques. These practical recommendations for using a comprehensive SET technique based on evidence-based human resource practices are critical sources of this article’s strength. This article is a reliable and dependable source of existing knowledge on the association between SET surveys and perceived student academic performance. Lohman L. recommends planful use of results coupled with behavioral approaches to performance appraisal. The article also highlights the importance of relying on multiple targeted stakeholders to collect helpful information that can help make SETs fair and objective.

The article by Curby et al. (2020) supports the findings, observations, and conclusions made by Lohman L. (2021, 151) article. This article is relevant to SET bias because it highlights the sources of variance in professor ratings attributable to learner bias in the teacher evaluation process. The research assesses the reactive importance of three-course rating facets: the course, instructor, and occasion. Curby et al. (2020, 44)’s findings indicate that a measurement error in the three-way interaction between the class, experience, and instructor accounts for the most variance in student ratings (24%). This knowledge is essential in the SET bias debate, as it indicates that SET surveys do not always reflect an instructor’s performance accurately or their quality of teaching. Both Lohman L. (2021, 151) and Curby et al. (2020, 44) suggest that relying solely on SET data for teaching evaluation and ranking may lead to bias and might not be sufficient for assessing a professor’s teaching effectiveness. These findings mean it is necessary to incorporate other evaluation methods, such as peer reviews in professor rating systems, to ensure that the assessments are unbiased and comprehensive.

Another closely related study by Feistauer, D. and Richter, T. (2018, 168) assessing the effect of prior subject interest and professor likeability as potential sources of bias expertly complement the findings by Lohman L. (2021, 151) and Curby et al. (2020, 44). The article found that instructors’ likability had a strong biasing effect on student ratings of their professors. In contrast, prior subject interest demonstrated a weak biasing impact in evaluating educators at the end of a course. Feistauer, D. and Richter, T. (2018, 170) suggest that the likability of a professor among students can impact SETs significantly. These findings by Feistauer, D. and Richter, T. (2018, 170), Lohman L. (2021, 151), and Curby et al. (2020, 44) highlight the potential bias of SETs that result from factors that are not directly related to teaching quality. This risk of preferences raises concerns about the validity of student evaluation of teachers as an effective measure of teaching prowess, instructor mastery of the contents, and ability to deliver in an understandable way that an audience of higher education learners can quickly grasp.

While the previous three articles focus on the issue of bias in the process of teacher evaluation, they fail to acknowledge the role of SET incentives in influencing student and faculty behavior. The article by Love, D.A. and J Kotchen, M. (2010, 152) bridges this gap in the literature by acknowledging the role SET-related incentives play in determining a professor’s teaching effort and in exacerbating the grade inflation problem. According to Love, D.A. and J Kotchen, M. (2010, 152), placing too much emphasis on end-of-term course and professor evaluations can exacerbate the problem of grade inflation and harm a professor’s teaching effort. This surprising finding suggests that professor evaluations of student teaching might only sometimes accurately reflect an educator’s teaching quality. The authors also caution that these SETs are constantly influenced by other factors, such as the incentive structure of academic institutions that are beyond assessing a teacher’s teaching effectiveness. Additionally, the article suggests that increasing emphasis on research productivity can The authors explain that SET surveys not only further decrease teaching effort but also present an incentive to inflate grades among professors to retain their hiring, promotion, and tenure contracts.

Another study by Mitchell, K.M. and Martin, J. (2018, 648) reveals that other than the external biases caused by factors other than those influencing teaching effectiveness, gender also plays a critical role in exacerbating the problem. The article examines the issue of gender bias in SET surveys within the political science discipline. Mitchell, K.M. and Martin, J. (2018, 649) cite previous research studies that have found evidence of gender bias in SETs. The researchers even used some studies that were controlled for instructor-specific attributes to isolate the impact of sex on professor evaluations by students. The key findings from the study found that female professors receive lower ratings than male professors. More so, Mitchell, K.M. and Martin, J. (2018, 651) showed evidence that students used various criteria such as a professor’s personality, gender, and appearance rather than their grading patterns and teaching abilities. The authors postulate that using SETs in professor hiring decisions is discriminatory against women.

2.2.1: Mitigating Bias in Student Evaluation of Teachers Surveys

Hoorens et al. (2021, 34) affirm this bias in their study by examining the effectiveness of self-affirmation in reducing gender bias in rating professors at the end of each semester. In their research, Hoorens V. and colleagues found that when learners are asked to engage in self-affirmation tasks before completing SETs has significant potential to reduce gender bias in their evaluation of professors. The study also found that male professors receive lower evaluations than their female counterparts following these self-affirmation tests just before administering SET surveys. This observation means that the timing of SET surveys also plays a role in determining how students rate their professors (McClain et al., 2018, 369). According to Hoorens et al. (2021, 34), their findings suggest that gender bias in SETs may involve overvaluing male professors rather than derogating female professors. The authors conclude that using self-affirmation tasks can be an effective intervention to mitigate gender bias in SETs.

Another article published in 2019 by Peterson et al. acknowledges that gender bias is an inherent problem in SETs that needs immediate attention, given the critical role these student evaluations of teaching play in professor hiring, promotion, and retention. However, contrary to the previous articles that covered gender bias in student evaluations of teaching (SETs) solely as a concept, Peterson et al. (2019, p.e0216241) conducted a randomized experiment to investigate how SETs designers can use a simple intervention in language to mitigate gender bias in professor rating processes. Their findings suggested that providing anti-bias language to students during the SET process can significantly reduce discrimination against female instructors. Learners in the anti-bias language treatment group ranked female professors considerably higher than students in the standard treatment group. Interestingly, the study found no differences between treatment groups for male instructors. Peterson et al.’s study align with previous articles such as Hoorens et al. (2021, 34), Mitchell, K.M., and Martin, J. (2018, 651) that demonstrated gender bias during professor evaluations of teaching effectiveness by students. However, this study goes beyond identifying the issue as a mere concept in higher education human resource literature to propose a potential solution of using anti-bias language intervention that is both simple and practical. The study also highlights the importance of developing practical and easy-to-implement solutions that address gender bias in SETs, given the outsized role professor ratings play in the evaluation, hiring, and promotion of higher education faculty.

2.2.2: Can SETs be a Reliable, Credible, and Fair Measure of Teaching Effectiveness?

In the face of existing knowledge, SETs play a critical role in influencing hiring, retention, and promotion decisions facing human resource managers of higher learning institutions. Scholars and researchers have shown that SETs help allow learners to give feedback about their learning experience but have proven unreliable, unfair, ineffective, and, in some cases, invalid (Esarey, J. and Valdes, N., 2020, 1116; Uttl et al., 2017, 22). Esarey and Valdes (2020; 1106) examine the assumptions underlying using SETs as an evaluation tool. In this article, Esarey and Valdes (2020; 1106) assume that SETs are reliable, unbiased, and, most importantly, valid. The authors used computational simulation to explore the implications of these assumptions under ideal conditions. The findings of their study revealed that where SETs are moderately correlated with teaching effectiveness, there still exist significant limitations to using SETs solely as the benchmark tools for a valid and effective measure of instructional quality. Uttl et al. (2017, 22) confirm this discrepancy in the correlation between SETs and teaching effectiveness by confirming that the two variables are unrelated. Esarey and Valdes (2020, 1119) thus recommend utilizing SETs for evaluating faculty accompanied by other multiple measures, including but not limited to student engagement measures and learning outcomes assessment, to produce fairer and more valuable results. This article is a critical source of literature on the credibility and validity of using SETs as it highlights the importance of understanding the limitations of these evaluation techniques, given their great potential for bias and vague association with teaching quality. Esarey and Valdes (2020) argue that carefully considering the strengths and weaknesses of SETs and using them alongside their practical, unbiased measures can help produce a more accurate and fair faculty evaluation (151).

2.3: SETs and Student Perspectives

Current literature has developed a deep interest in understanding the students’ perspectives about SETs and how these insights can be used to inform higher education policy. For instance, Hadad et al. (2020, 447) explore the perspectives of students and faculty regarding their perceived relative importance of various teaching evaluation criteria, focusing on how students rate their professors based on these criteria. The authors note that SET surveys have a serious shortcoming of assigning equal weights to multiple criteria instead of their proportional weights.

Hadad et al. (2020, 447) acknowledge that this shortcoming still needs to be addressed, and SETs continue to be widely used to measure student satisfaction in higher education. Borch et al. (2020, 83) also acknowledge this major shortcoming associated with SET by reporting that educators found SET surveys unsuitable for educational enhancement. The authors argue that understanding the relative importance of these criteria from students’ perspectives can help narrow the criteria to leave only the most important to learners. To demonstrate how policymakers and stakeholders in higher education can assign accurate weight to various SET criteria, Hadad et al. (2020, 447) used an analytic hierarchy process methodology to capture the weights of various SET criteria from the perspectives of learners and educators. The researchers then used the SET feedback to analyze the students’ actual ratings of instructors. The results from the analytic hierarchy process methodology revealed statistically significant differences in the weights of SET criteria. This finding means that learners and their instructors have different perceptions of the importance of various criteria.

A closely related study by Fauth et al. (2020, 1284) also notes a wide discrepancy between student perspectives of teaching quality, as evidenced in their ratings of instructors and how observers view the same instructors’ teaching effectiveness. Fauth et al. (2020, 1284) thus caution policymakers to remain objective when interpreting student evaluation of educators’ results as indicators of teacher quality. In their study, Faith B. and colleagues presented three findings from three experiments conducted in Germany seeking to establish the stability of teaching quality measures across grades and time. The first finding indicated that factors, such as the inherent instability of students’ professor rating patterns over time, were outside of the teacher’s control. Another study by Feistauer, D. and Richter, T. (2018, 168) affirms this observation by highlighting that factors outside those assessing teaching quality, such as course likability and prior subject interest, influence how students rate their professors. More specifically, the research showed that likability has a strong biasing effect on learners’ evaluations of instructional quality, while prior subject interest has a weak biasing effect. Samuel, M.L. (2021, 159) also found external factors, such as class format and seating arrangement, to impact how learners evaluate teaching effectiveness. These factors are related to the learning environment, diverse student perspectives, internal biases, and personal differences, as opposed to an objective assessment of the teacher’s ability to disseminate course objectives for improved academic performance.

Fauth et al. (2020, 1284)’s second finding indicated that teaching quality emerges in interactions between teachers and students and, thus, is not a stable teacher characteristic. The third finding showed that teaching quality, as rated by students and external observers, varied considerably between classes. Fauth et al. (2020, 1284) explained that differences in teaching quality are related to student learning and motivation in a class. These conclusions suggest that classroom characteristics, such as learner-educator engagement and student motivation in class, can significantly influence the quality of teaching and thus should be included in the student evaluating teaching quality surveys.

3.0: Methodology

This study used mixed methods using quantitative parametric and non-parametric statistical methods with a qualitative systematic literature review to examine students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of SETs in impacting academic outcomes. The qualitative thematic analysis of the literature approach helped cross-examine a set of 15 peer-reviewed journal articles to reveal the unique perceptions of students regarding the effectiveness of SETs as practical assessment tools for measuring teaching effectiveness as well as identify the key themes in the existing literature that can help improve the quality of higher education. This way, the study would achieve its main objective of bridging the gap in the literature on learners’ general perception of using SET surveys to give good, accurate, and reliable learning experience feedback. This study’s findings can help inform learners about reliance on SET surveys and professor ratings to make lifelong decisions such as course selection using mixed methods to interrogate the qualitative and empirical evidence of students’ perception of the effectiveness of professor rating systems to improve the quality of higher education. The hypotheses below helped achieve this study objective.

3.1: Study Hypotheses

Null hypothesis 1: Students believe professor ratings have no statistically significant effect on their Academic Outcomes

Students believe professor ratings do not significantly impact their learning outcomes and thus do not make course selection recommendations based on a professor’s SETs scores.

Ha=Higher education learners believe professor ratings significantly impact their academic success and thus make critical course selection decisions and recommendations based on these instructor SET rankings.

3.2: Sampling Techniques

3.2.1. Secondary Data

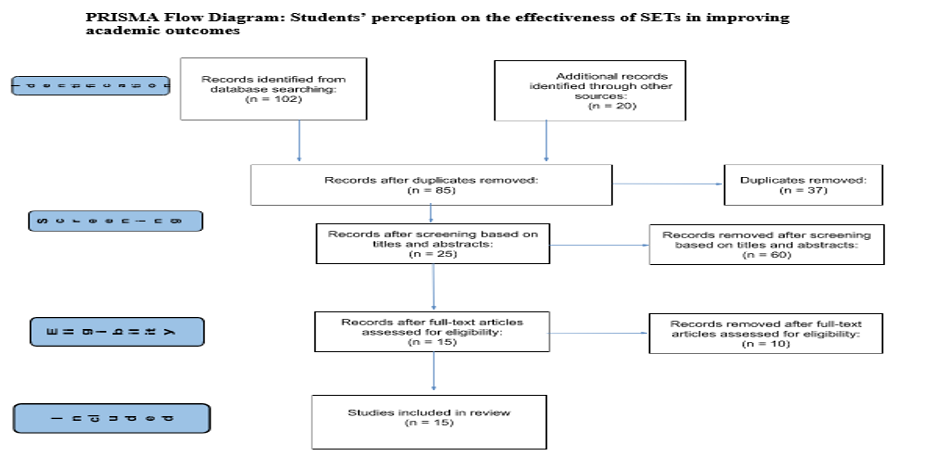

This study used thematic analysis of existing literature to collect relevant information and knowledge on the known association between SETs and learners’ academic performance. The researchers used keyword searches on recommended databases such as Google Scholar, Web of Science, Scopus, and JSTOR to identify the relevant articles for inclusion in the literature review. Some of the keywords used include ‘Student evaluations of teachers (SET) surveys & teaching effectiveness,’ ‘professor ratings by the student,’ ‘student perception of the effectiveness of SETs,’ ‘reliability and validity of SETs,’ ‘bias in SETs,’ ‘effectiveness of teacher rating systems,’ and ‘factors affecting student ratings of professors/instructor/teachers/educators’ among others. The PRISMA flow diagram below summarizes collecting and analyzing the evidence from secondary sources.

After collecting the required articles, the researcher analyzed them for content using their fully accessible pdf online and complete abstracts where sources were unavailable. The findings were categorized into three themes covered in the picture shared in the literature review section.

3.2.1. Primary Data

The researchers used a structured questionnaire with 21 questions assessing the gender of respondents, student perception, and beliefs about the effectiveness of SETs in informing critical academic decisions such as course selection and evaluation of teaching effectiveness. This question is attached in Appendix 1.0. The questionnaire is close-ended, with responses to questions coded using a Likert scale. The questionnaire was administered in a classroom setting where students were asked to fill out the questionnaire just like they would have done with a student’s evaluation of a teaching survey. A convenient sampling technique was used to recruit 30 male and female participants studying at an American University and currently enrolled in a course for more than one semester. All responses were collected, coded, and saved in a . CSV file ready for analysis using JASP Software version 0.17.1. The results of the data analysis are presented below.

4.0 Data Analysis, Interpretation, and Discussion

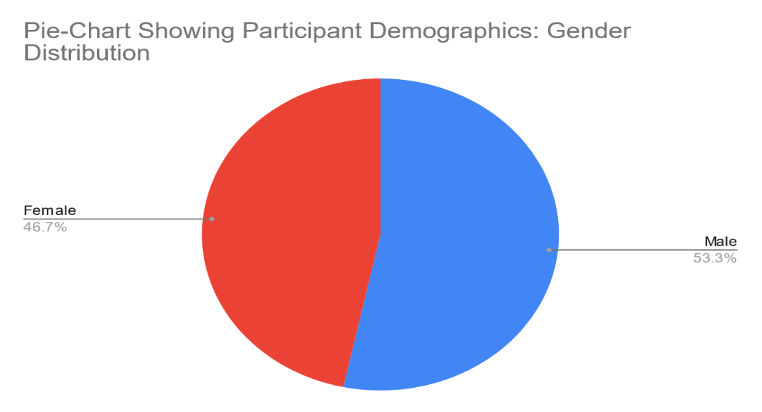

4.1: Pie-Chart: Participant Demographics

A sample of 30 students (n=30) currently enrolled in an American University participated in answering the study questionnaire. Among the participants were 16 male students and 14 female students, as shown in the pie chart below.

In percentage form, male respondents comprised 53.3% of all participants, while female students made up the remaining 46.7%.

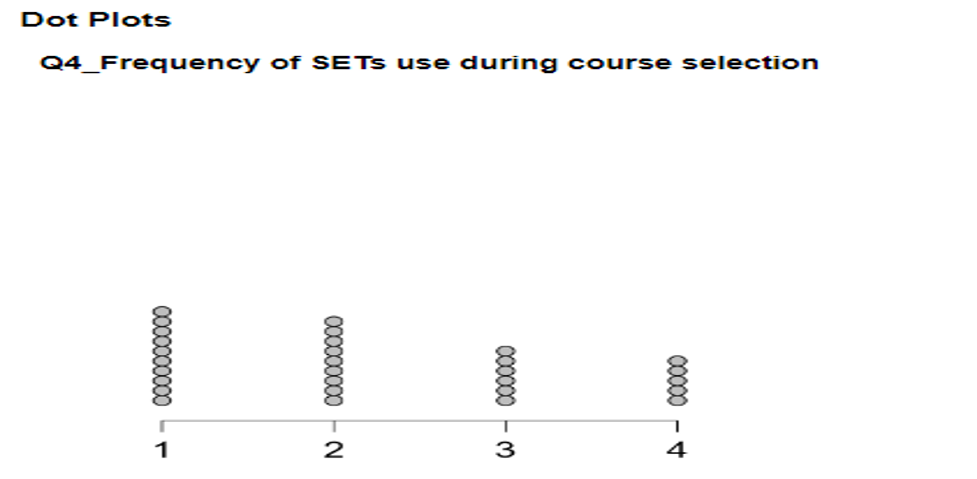

4.2: Bar Graph Showing Frequency of SETs Use During Course Selection Among Participants

Most of the respondents who completed the questionnaire said they ” use SETs to make course selection decisions, as shown by the Dot Plots bar graph below.

As shown in the dot plot diagram above, 10 participants said they rarely use SET to make course selection decisions. In contrast, nine respondents said they sometimes used professor ratings to decide which course to take at the University. Only 6 participants said they often use SETs, with only five reported always using SETs before making course selection decisions.

4.3. Non-Parametric Chi-Square Test for Evaluating the Study Hypothesis

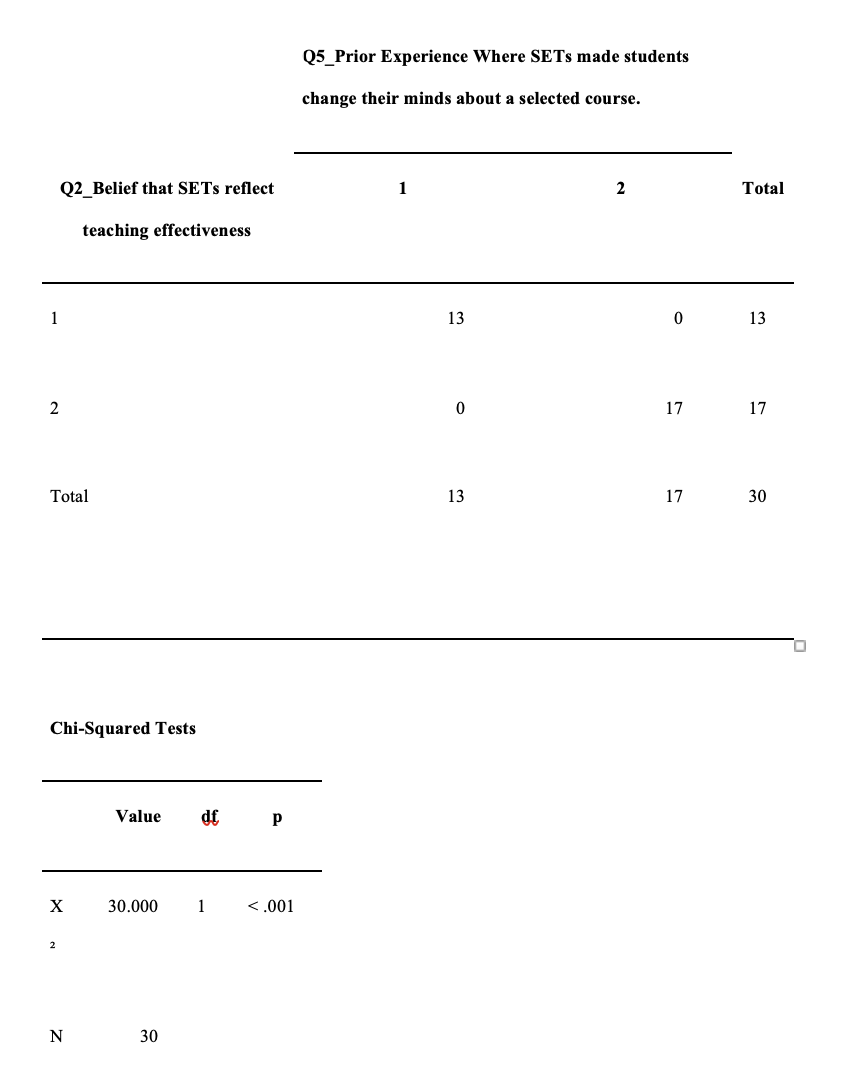

This study’s null hypothesis states that students believe professor ratings do not significantly impact their learning outcomes. Thus, they do not make course selection recommendations based on a professor’s SETs scores. Consequently, the alternative hypothesis that is the crux of this study postulates that higher education learners believe professor ratings significantly impact their academic success and thus make critical course selection decisions and recommendations based on these instructor SET rankings. A chi-square test was selected for this analysis for its ability to work with categorical data (such as the yes/no response to the question of whether or not learners strongly believe that professor ratings impact academic outcomes) without the need for assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity (Turhan, NSNS, 2020, 575). This study notably used questionnaire queries 2 and 5 to test this hypothesis. The JASP output is shown below. First is the contingency tables.

Table: Contingency Tables: Student belief that SETs reflect teaching effectiveness versus prior experience where students made course selection decisions based on SETs scores/professor ratings.

When conducting a chi-square test in JASP, a contingency table helps organize and summarize the frequencies of the variables under analysis when testing the null hypothesis. The contingency tables are the gateway to conducting practical chi-square analysis as it tabulates the observed and expected observations against the sample total for a better visual representation of findings. The resultant chi-square table from JASP analysis indicates a highly statistically significant p-value of <0.001 (less than theoretical p=0.05), meaning that the null hypothesis is rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis that higher education learners believe professor ratings have a significant impact on their academic success and thus make critical course selection decisions and recommendations based on these instructor SET ranking. This finding is consistent with those from existing literature, such as the study by (Lohman, L., 2021, p.101008), Finefter-Rosenbluh, I. (2020, 747), Feistauer, D. and Richter, T. (2018, 168), and Hadad et al. (2020, 447) showed a significant impact of SETs on overall academic quality. Qualitative and quantitative evidence reveals that it is statistically associated with their belief that professor ratings influence academic performance. SET rankings can be used to make vital course selection decisions.

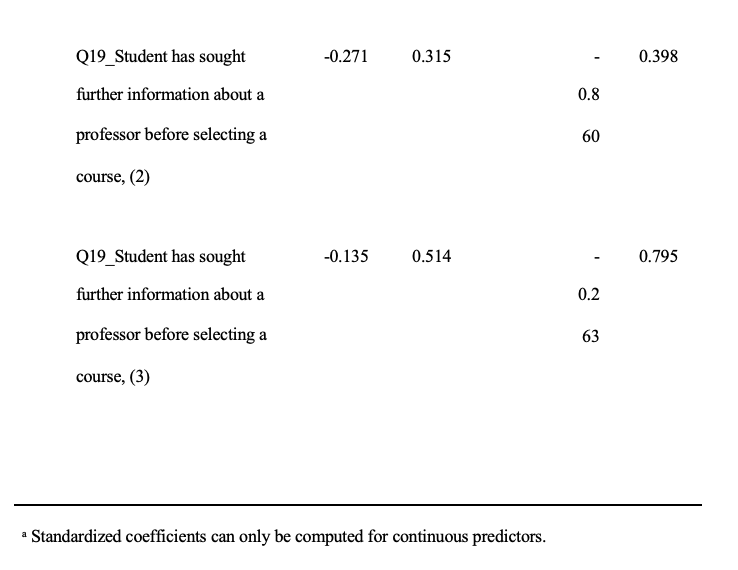

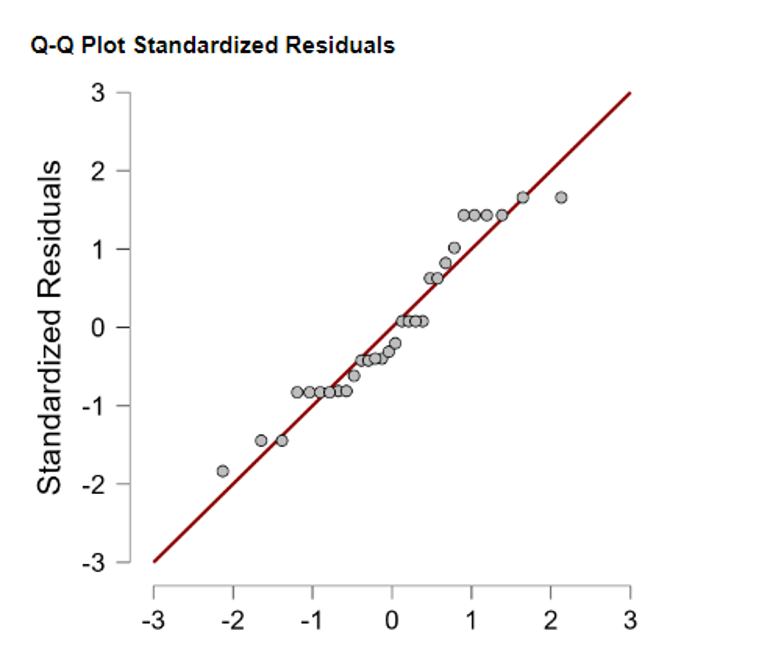

4.4: Using JASP Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for Data Model Identification

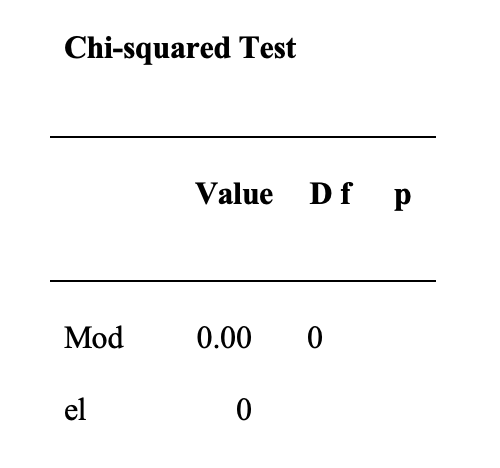

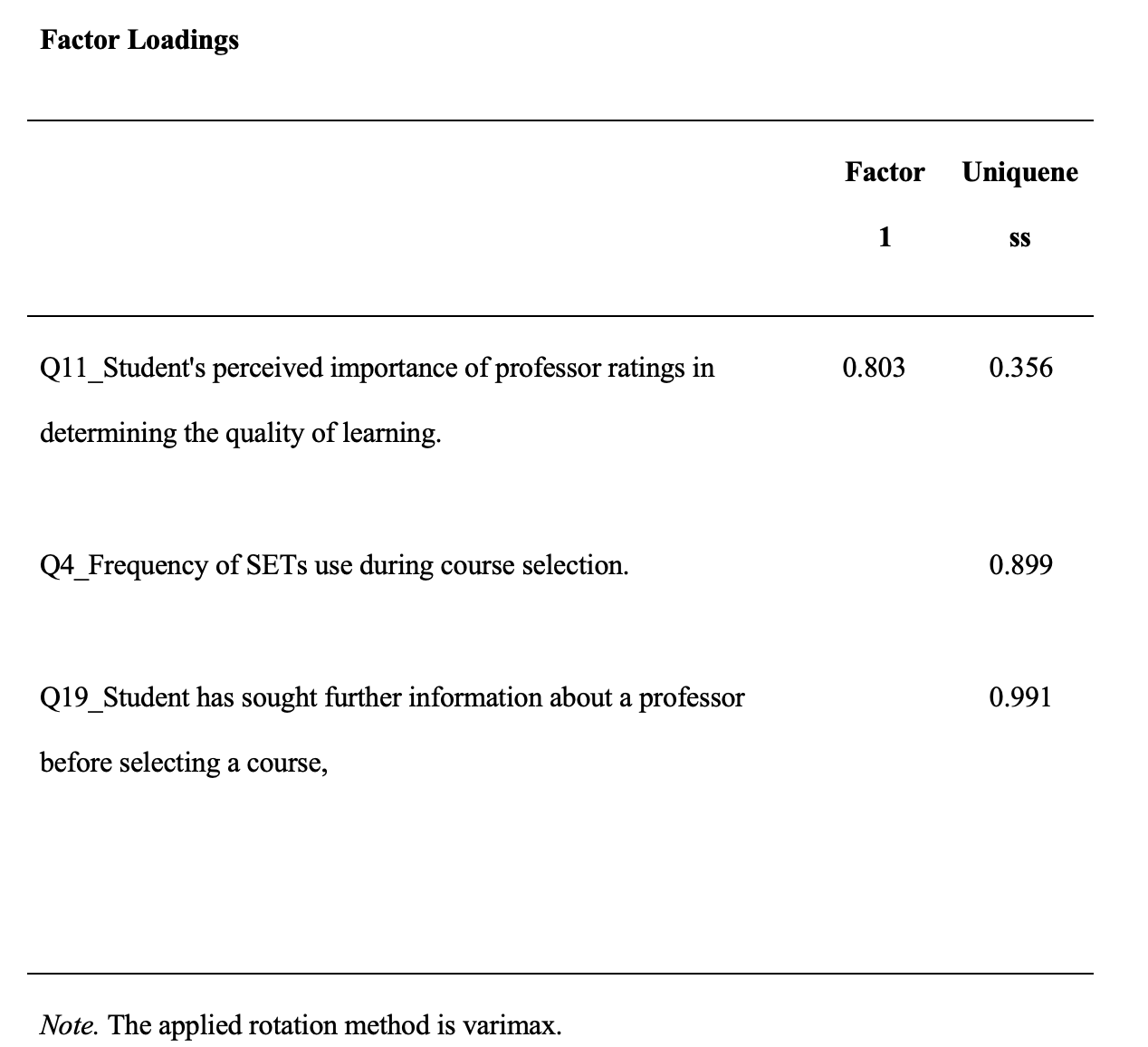

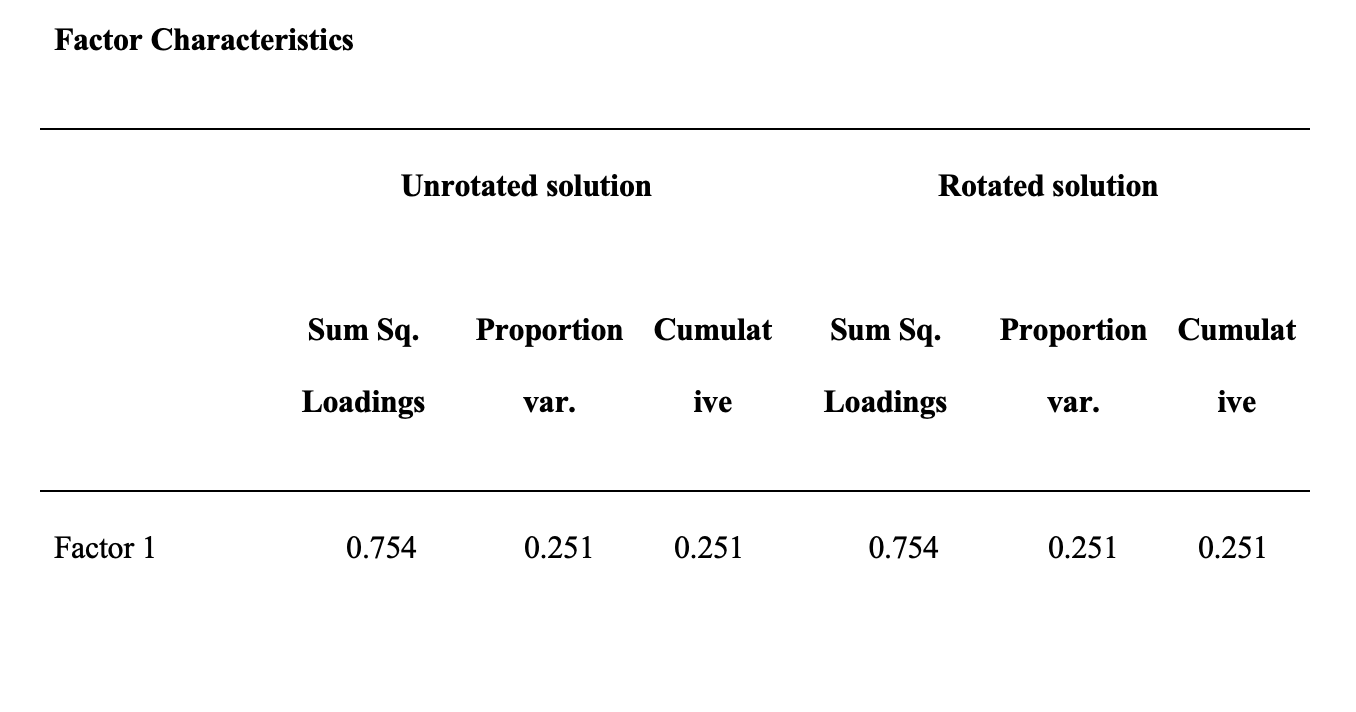

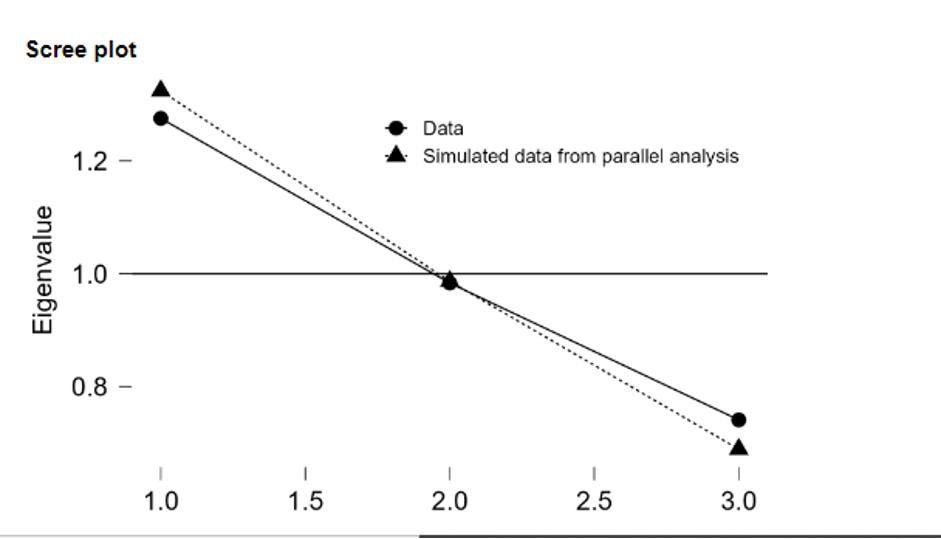

The researchers used exploratory factor analysis (EFA) statistical techniques to test the validity of the theoretical model explaining the relationships among the 20 variables from Q1-Q20 of the questionnaire. This technique helped confirm whether the observed data fit or contradicted a pre-specified theoretical model identified from the thematic literature review. The knowledge gained from the literature review on the intervening variable/confounding factors guided the researchers in identifying the observed variables expected to be loaded on each factor and the direction of their loadings. The number of factors was based on parallel analysis with the rotation method set to orthogonal varimax and the factoring method used being the maximum likelihood approach. A scree plot tabulated this observed relationship against the simulated parallel analysis. The JASP results are shown in the tables and graphs below.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

The Chi-squared test has a value of 0.000, suggesting that the model is a good fit for the data. The factor loadings indicate that out of the 20 possible factors derived from questionnaire responses, only three are strongly associated with Factor 1: Q11_Student’s perceived importance of professor ratings in determining the quality of learning. The model also explains the uniqueness of each item or the proportion of its variance that is not accounted for by the factor under study. The factor characteristics table reveals a rotated solution with one factor whose eigenvalue is 0.754, accounting for 25.1% of the variance in the data. The unrotated solution in the dataset equally has one factor accounting for the same proportion of variance. As expected, a factor correlations table indicates that ‘student’s perceived importance of professor ratings in determining the quality of learning’ is perfectly correlated with itself (r=1).

A scree plot analysis shows that the observed data intersect with the simulated data from parallel analysis at eigenvalue. The simulated data provides a reasonable estimate of the eigenvalues for the population from which the sample was drawn. This intersection point, also known as the scree plot “elbow,” is often used as a benchmark criterion for determining the number of factors to retain in a study.

From the scree plot analysis, only two questionnaire items, namely ‘Q4_Frequency of SETs use during course selection’ and ‘Q19_Student has sought further information about a professor before selecting a course’ should be retained in the model mapping the student perceptions of the importance of SET survey ratings in making critical course selection decisions.

4.5 Correlation Analysis:

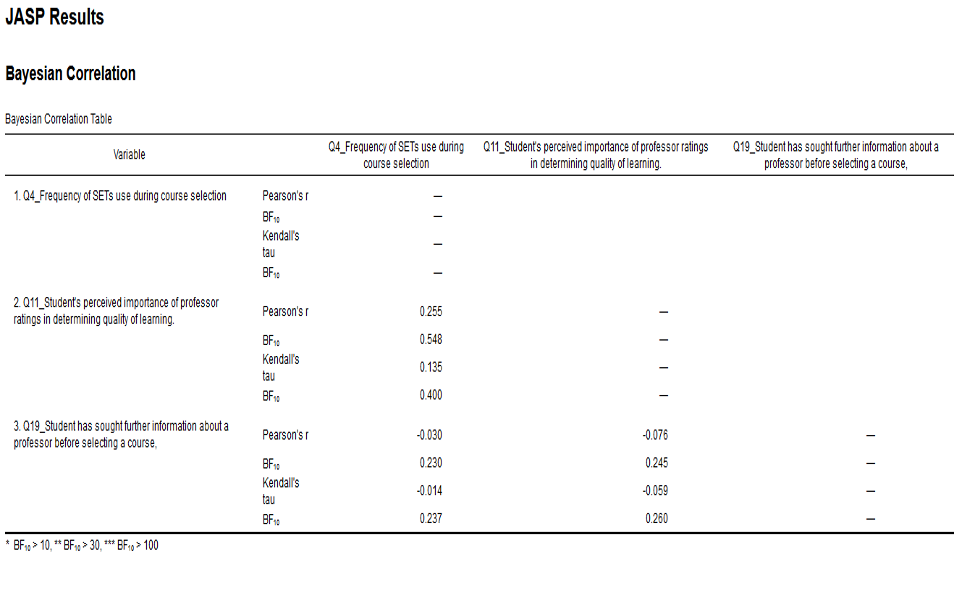

This report used a Bayesian correlation analysis because the identified factors are ordinal categorical data with a natural order. The table below shows the results of the correlation between students’ perceived importance of professor ratings in determining the quality of learning and the Frequency of SETs usage during course selection.

The correlation between students’ perceived importance of SET survey ratings and the frequency of professor ratings use during course selection is a weak association evidenced by the low Pearson’s r of 0.255. The association between student behavior of seeking further information about a professor beyond the SET ratings before selecting a course and student perception of the student evaluation of teachers’ scores is a weak negative correlation with a Pearson’s r of -0.076.

4.6: Regression Analysis to test for Causality

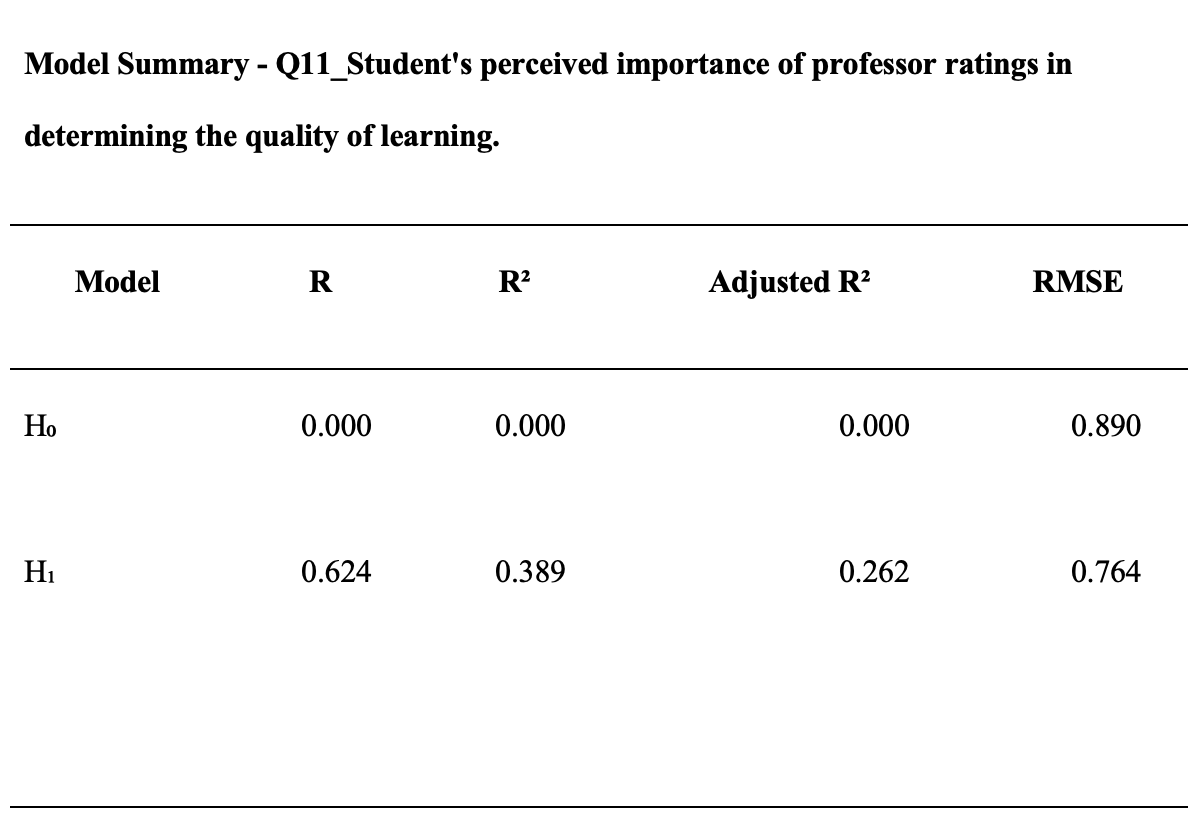

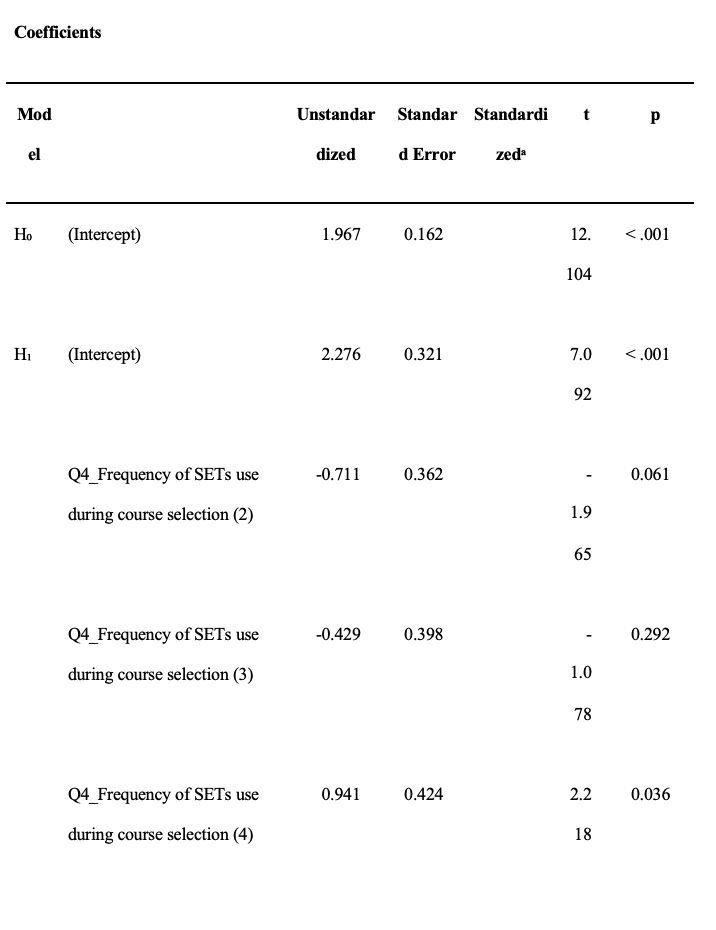

This report used JASP linear regression analysis to examine the direction of correlation (Causality) between the higher education learners’ perceived importance of SET survey ratings in determining the quality of professor’s teaching effectiveness against two predictor variables identified from the exploratory factor analysis, which include: Q4_Frequency of professor rating survey information use during course selection and Q19_learners’ tendency to consult further information about a professor, e.g., through syllabi consultation or academic mentor advice before selecting a course. The table below summarizes the key findings.

Linear Regression

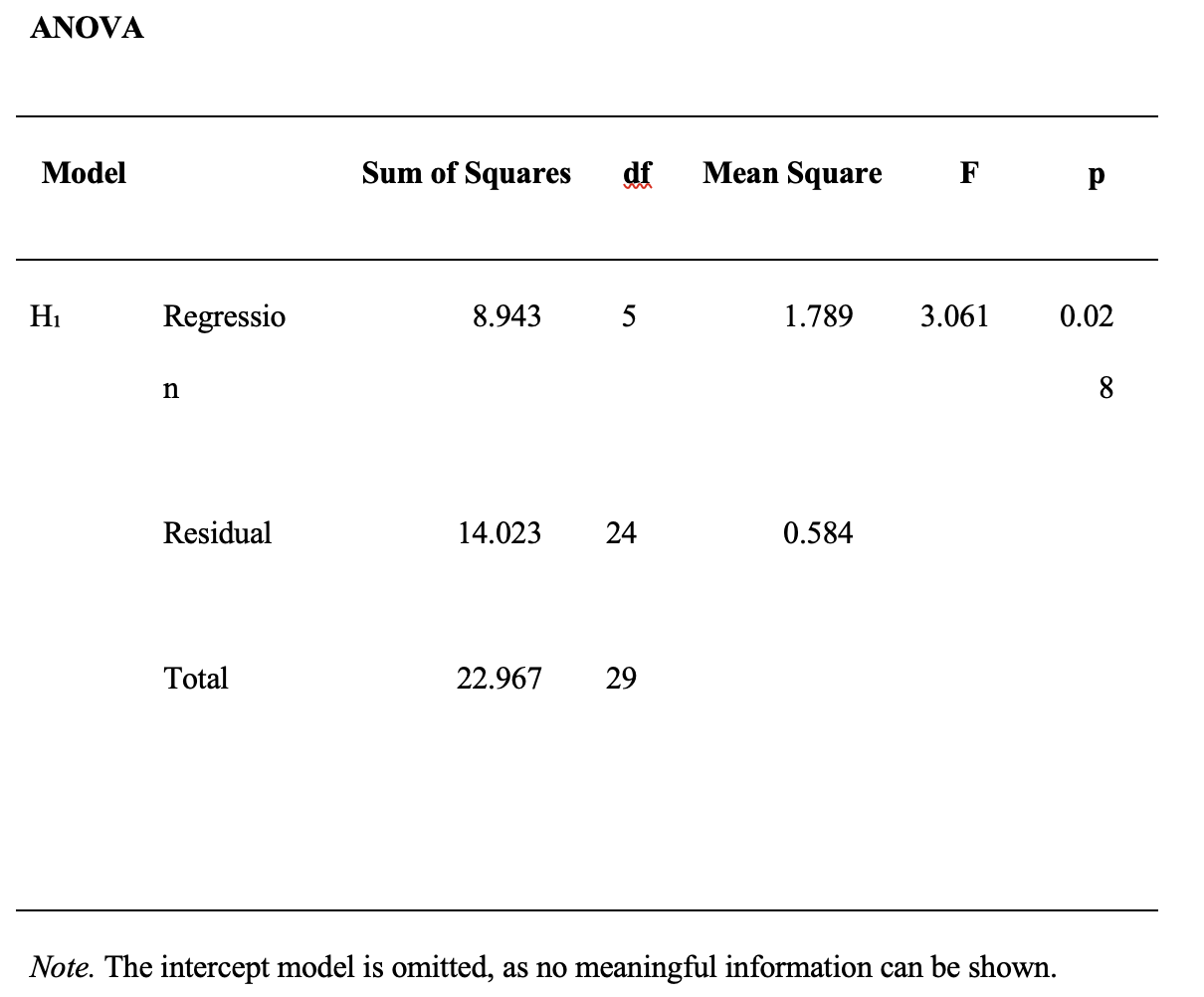

The Model Summary table indicates that this model explains a significant proportion of the variance in the dependent variable (R-squared value of 0.389) after adjustments. The ANOVA table shows a statistically significant model (F=3.061, p=0.028), meaning that the two predictor variables (Q4 & Q19) significantly affect the higher education learners’ perception of the effectiveness of SET ratings on academic outcomes. The Q-Q plot below shows that residuals are normally distributed, meaning the model assumptions have not been violated.

Fitting a line of best fit to the Q-Q plot indicates that the residuals fall in an almost straight line meaning the model is reliable, and data is normally distributed.

The findings of this regression model add to the knowledge of factors affecting students’ perceived importance of SET surveys in making lifelong course selection decisions and their effectiveness in assessing professors’ teaching quality. The findings are consistent with prior studies in existing literature, such as Curby et al. (2020, 44), Hadad et al. (2020, 447), and Fauth et al. (2020, p.1284) that found factors outside of the teacher’s control that influences a student’s perception of the significance of professor ratings in evaluation instructional quality in higher education settings.

5.0: Recommendations and Conclusion

This study’s focus was on evaluating the perceptions of higher education learners regarding the effectiveness of student evaluation of teacher’s surveys in informing course selection choices and the subsequent impact on academic outcomes through mixed methods. The qualitative thematic analysis of current literature identified unique student perspectives on the importance and effectiveness of SET surveys as practical assessment tools for measuring a professor’s teaching quality. The thematic analysis also identified key themes in the existing literature that scholars, policymakers, and students believe can help improve the quality of higher education. This report additionally used a 21-item structured questionnaire administered to 30 participants data to collect data that was later coded and analyzed using JASP software. The quantitative analysis findings showed that most participants rarely or sometimes use professor ratings to decide which course to take at the University. Only a few students report ‘always using’ SETs ratings before deciding which course to take. Further analysis revealed no statistically significant effect of SETs on academic outcomes among students from the learner’s perspective. However, learners who use SET to make decisions tend to have higher perceived importance of these professor ratings in affecting course selection decisions and improving the quality of higher education.

5.1 Recommendations

Therefore, this report recommends that;

- Higher education institutions and their human resource departments must consider alternative methods for measuring teaching effectiveness. As a matter of qualitative and quantitative evidence, this report found that providing feedback to instructors relying solely on SETs does not lead to improved academic outcomes.

(i) These alternative methods include peer-to-peer teacher reviews, student-teacher engagement surveys, engaging learners in self-affirmation tasks that Hoorens et al. (2021) recommended before undertaking SETs to reduce gender bias against female educators and using anti-bias language as Peterson et al. (2019) advised.

- Future research should be conducted to identify the underlying causes of low student dependency on SET survey information to make course selection decisions.

- Higher learning institutions and their human resource departments should refrain from using SETs ratings to make critical professor hiring, firing, and promotion decisions because these surveys are deeply flawed, unfair, biased, and discriminatory against female educators.

- Higher education policymakers should fund studies to explore how learning institutions can encourage students to use SETs as practical assessment tools for measuring teaching effectiveness to improve the teacher’s instructional quality.

Bibliography

- Borch, I., Sandvoll, R. and Risør, T., 2020. Discrepancies in purposes of student course evaluations: what does it mean to be “satisfied”? Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Accountability, 32(1), pp.83-102. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11092-020-09315-x

- Curby, T., McKnight, P., Alexander, L. and Erchov, S., 2020. Sources of variance in end-of-course student evaluations. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(1), pp.44-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2018.07.009

- Esarey, J. and Valdes, N., 2020. Unbiased, reliable, and valid student evaluations can still be unfair. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(8), pp.1106-1120. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1724875

- Fauth, B., Wagner, W., Bertram, C., Göllner, R., Roloff, J., Lüdtke, O., Polikoff, M.S., Klusmann, U. and Trautwein, U., 2020. Don’t blame the teacher. The need to account for classroom characteristics in evaluations of teaching quality. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(6), p.1284. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000416

- Feistauer, D. and Richter, T., 2018. Validity of students’ evaluations of teaching: Biasing effects of likability and prior subject interest. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 59, pp.168-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2018.07.009

- Finefter-Rosenbluh, I., 2020. ‘Try walking in my shoes’: teachers’ interpretation of student perception surveys and the role of self-efficacy beliefs, perspective taking and inclusivity in teacher evaluation. Cambridge Journal of Education, 50(6), pp.747-769. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2020.1770692

- Hadad, Y., Keren, B. and Naveh, G., 2020. The relative importance of teaching evaluation criteria from the points of view of students and faculty. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(3), pp.447-459. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1665623

- Hoorens, V., Dekkers, G. and Deschrijver, E., 2021. Gender bias in student evaluations of teaching: Students’ self-affirmation reduces the bias by lowering evaluations of male professors. Sex Roles, 84(1-2), pp.34-48. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11199-020-01148-8

- Lohman, L., 2021. Evaluation of university teaching as sound performance appraisal. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 70, p.101008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101008

- Love, D.A. and J Kotchen, M., 2010. Grades, course evaluations, and academic incentives. Eastern Economic Journal, 36, pp.151-163. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/eej.2009.6

- McClain, L., Gulbis, A. and Hays, D., 2018. Honesty on student evaluations of teaching: effectiveness, purpose, and timing matter! Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(3), pp.369-385.

- Mitchell, K.M. and Martin, J., 2018. Gender bias in student evaluations. PSPS: Political Science & Politics, 51(3), pp.648-652.

- Peterson, D.A., Biederman, L.A., Andersen, D., Ditonto, T.M. and Roe, K., 2019. Mitigating gender bias in student evaluations of teaching. PloS one, 14(5), p.e0216241.

- Samuel, M.L., 2021. Flipped pedagogy and student evaluations of teaching. Active Learning in Higher Education, 22(2), pp.159-168.

- Turhan, N.S.N.S., 2020. Karl Pearson’s Chi-Square Tests. Educational Research and Reviews, 16(9), pp.575-580.

- Uttl, B., White, C.A. and Gonzalez, D.W., 2017. Meta-analysis of faculty’s teaching effectiveness: Student evaluation of teaching ratings and student learning are not related. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 54, pp.22-42.

Appendices

Appendix 1.1: Questionnaire

This questionnaire examines the topic ‘STUDENT’S PERCEPTION OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THEIR PROFESSOR RATING ON THEIR ACADEMIC OUTCOMES.’ All responses are highly valued and will be used for academic purposes only. No information given below will be used for commercial purposes. We will also observe all ethical guidelines from our University under the strict guidelines of our research instructor. Please keep the responses truthful and honest.

Section 1: Personal Information

Please select your gender to proceed.

(1=Female, 2= Male).

Section 2: Student Perception of and Experiences with Professor Ratings

- Have you ever used professor ratings to guide your course selection process before?

(1=No, 2=Yes).

- Do you believe the professor ratings accurately reflect an instructor’s teaching effectiveness?

(1=Disagree , 2= Agree)

- Have you ever experienced a negative or positive encounter with a professor whose ratings differed from your expectations and experiences?

(1=No, 2=Yes)

- How often do you consult professor ratings before deciding which course to take in a higher learning institution?

(1=Rarely , 2= Sometimes, 3=Often, 4=Always)

- Has your knowledge of a professor’s ratings made you change your mind about taking a course before?

(1=No , 2= Yes)

- Do you believe that higher learning institutions should use professor ratings when making critical decisions about a professor’s hiring, retention, and promotion decisions?

(1=Disagree, 2=Agree)

- Should policymakers publicly make professor ratings available to all students and their guardians?

(1=No, 2=Yes)

- Have you ever reviewed or rated a professor on a course evaluation or other platform?

(1=No, 2=Yes)

- Do you strongly believe that your professor’s ratings have influenced your academic performance in any way?

(1=No, 2=Yes)

- Have you ever used a professor’s rating to recommend a course to a friend or classmate?

(1=No, 2=Yes)

- On a scale of very important to somewhat important, how important do you believe instructor ratings are in determining the overall quality of your education?

(1= Important, 2= Somewhat important, 3= Very important)

- Have you ever been positively or negatively surprised by a professor’s teaching effectiveness after you viewed or learned of their ratings?

(1=No, 2=Yes)

- Have you ever considered rating or reviewing a professor negatively but ultimately chose not to?

(1=No, 2=Yes)

- Should teacher ratings be required to include a qualitative comments section (optional) to supplement the numerical ratings?

(1=No, 2=Yes)

- Have any professional, mentor, or guardian given you academic advice that recommended courses based on a professor’s rating?

(1=No, 2=Yes)

- Do you believe that professor ratings should assess other factors, such as accessibility or grading policies beyond teaching effectiveness?

(1=No, 2=Yes)

- Have you personally experienced a professor whose ratings did not accurately reflect their teaching effectiveness currently or in the past?

(1=No, 2=Yes)

- When selecting courses alongside these professor ratings, how do you typically use essential information, such as course descriptions or syllabi?

(1=No, 2=Yes, 3= Syllabi)

- Have you ever sought out additional information about a professor beyond their rating selecting a course?

(1=No, 2=Yes)

- Should policymakers use student-suggested improvements to include new items in professor ratings for better academic success?

(1=No, 2=Yes)

The End!

Thank you for your time and honest responses.

Disclaimer: Participant Privacy

All data will be collected and analyzed anonymously, recorded in a credible database with encrypted passwords, and shared with no third parties beyond the faculty team at our University.

Appendix 2.0:Theme Categorization for Literature Review

SETs: 4 Key Themes, 1 Intersecting theme (impact on education)

Theme 1: Reliability and Validity of SETs

- Curby, T., McKnight, P., Alexander, L. and Erchov, S., 2020. Sources of variance in end-of-course student evaluations. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(1), pp.44-53.

- Feistauer, D. and Richter, T., 2018. Validity of students’ evaluations of teaching: Biasing effects of likability and prior subject interest. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 59, pp.168-178.

- Lohman, L., 2021. Evaluation of university teaching as sound performance appraisal. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 70, p.101008.

- Love, D.A. and J Kotchen, M., 2010. Grades, course evaluations, and academic incentives. Eastern Economic Journal, 36, pp.151-163. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/eej.2009.6

- Mitchell, K.M. and Martin, J., 2018. Gender bias in student evaluations. PSPS: Political Science & Politics, 51(3), pp.648-652.

Theme 2: Bias in SETs

- Peterson, D.A., Biederman, L.A., Andersen, D., Ditonto, T.M. and Roe, K., 2019. Mitigating gender bias in student evaluations of teaching. PloS one, 14(5), p.e0216241.

- Uttl, B., White, C.A. and Gonzalez, D.W., 2017. Meta-analysis of faculty’s teaching effectiveness: Student evaluation of teaching ratings and student learning are not related. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 54, pp.22-42.

- Esarey, J. and Valdes, N., 2020. Unbiased, reliable, and valid student evaluations can still be unfair. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(8), pp.1106-1120.

- Love, D.A. and J Kotchen, M., 2010. Grades, course evaluations, and academic incentives. Eastern Economic Journal, 36, pp.151-163.

- Hoorens, V., Dekkers, G. and Deschrijver, E., 2021. Gender bias in student evaluations of teaching: Students’ self-affirmation reduces the bias by lowering evaluations of male professors. Sex Roles, 84(1-2), pp.34-48.

Theme 3: SETs and Student Perspectives

- Borch, I., Sandvoll, R. and Risør, T., 2020. Discrepancies in purposes of student course evaluations: what does it mean to be “satisfied”? Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Accountability, 32(1), pp.83-102.

- Hadad, Y., Keren, B. and Naveh, G., 2020. The relative importance of teaching evaluation criteria from the points of view of students and faculty. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(3), pp.447-459.

- McClain, L., Gulbis, A. and Hays, D., 2018. Honesty on student evaluations of teaching: effectiveness, purpose, and timing matter! Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(3), pp.369-385.

- Fauth, B., Wagner, W., Bertram, C., Göllner, R., Roloff, J., Lüdtke, O., Polikoff, M.S., Klusmann, U. and Trautwein, U., 2020. Don’t blame the teacher. The need to account for classroom characteristics in evaluations of teaching quality. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(6), p.1284.

- Finefter-Rosenbluh, I., 2020. ‘Try walking in my shoes’: teachers’ interpretation of student perception surveys and the role of self-efficacy beliefs, perspective taking and inclusivity in teacher evaluation. Cambridge Journal of Education, 50(6), pp.747-769.

write

write