The persistence of healthcare inequalities in Saudi Arabia poses various challenges in ensuring equitable access to quality healthcare services. Socioeconomic disparities, regional variations, and gender-related norms contribute to the uneven distribution of healthcare resources and outcomes. Despite being available and affordable, spatial accessibility to healthcare among all people leads to a healthy generation (Khashoggi & Murad, 2021). The effect of societal factors on health disparities, particularly in relation to Coronary Heart Disease (CHD), remains high, which negatively influences health outcomes. The study proposes a comprehensive approach and government policies that integrate Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and targeted health interventions to address these inequalities effectively, yielding a more equitable and inclusive healthcare system in the country.

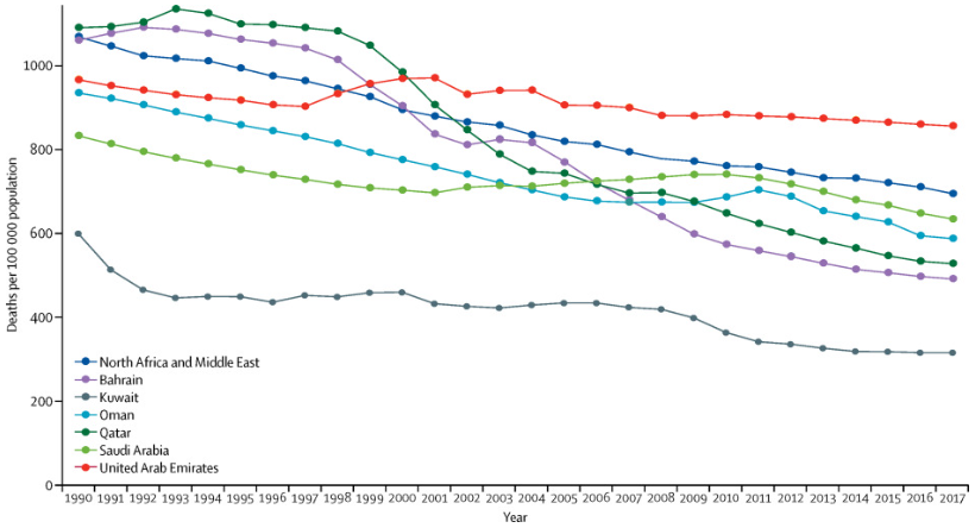

The primary burden of poor health is loss of life. As illustrated in Figure 1, diseases lead to premature deaths, which negatively interfere with health outcomes. These deaths can be associated with the widespread disparities in healthcare provision, which caused many people to succumb to diseases that could have been prevented or treated in time.

Figure 1: Mortality in Saudi Arabia, with respect to the other Gulf Cooperative Council Countries, North Africa and the Middle East GBD region from 1990 to 2017 (Tylovolas et al., 2020).

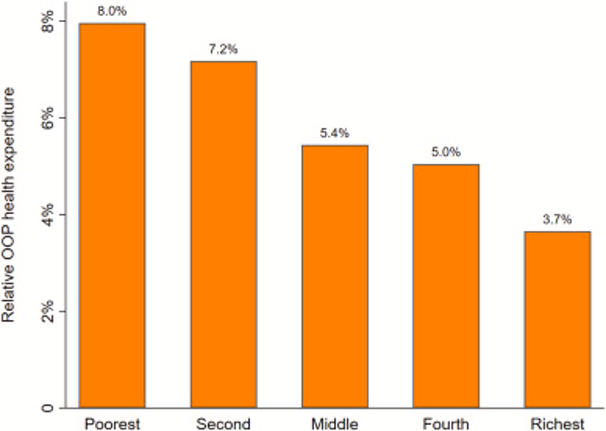

Like in many other countries, health inequality and inequity in Saudi Arabia are primarily influenced by societal and political dynamics. Nevertheless, Saudi Arabia has made significant progress in healthcare infrastructure and services. The healthcare system has, however, not been integrated into the social and cultural frameworks within the country. Having healthcare disparities within the country affects the welfare of people experiencing poverty, who incur unnecessary out-of-pocket healthcare expenditures (Al-Hanawi, 2021). Figure 2 demonstrates the effects of inequalities among various social classes. Subsequently, considerable disparities in health outcomes, particularly related to Coronary Heart Disease (CHD), affect the overall well-being of the Saudi community, which leads to reduced health outcomes.

Figure 2: Inequalities in out-of-pocket health expenditure (Al-Hanawi, 2021).

Evidence for Inequalities in Health Outcomes in Saudi Arabia

Currently, Saudi Arabia operates on a national healthcare model, where the government is responsible for providing primary healthcare services. Patients enjoy free healthcare services, supplemented by private hospitals and primary healthcare centers (Alharbi, 2018). The current model experiences various challenges, such as understaffing, shortage of drugs, and low quality of healthcare. The current hospital-to-population ratio is low, implying that the healthcare sector is too strained to serve the needs of the people efficiently.

Various studies have been completed on the inequalities in Saudi Arabia with respect to the effect it has on health outcomes. Gender-based inequalities are prevalent in the country and negatively influence health outcomes among men and women. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that gender inequality in Saudi Arabia threatens economic development and population health (Al-Hanawi & Chirwa, 2021). The extensive effect on economic statuses interferes with healthcare quality among underprivileged genders.

Adopting a culture where society participates in health promotion activities, such as health checkups and communal physical activities, can promote overall health outcomes. A health-conscious community avoids frequent hospital visits and cuts down the cost of healthcare. Low-threshold activities, community sports, can be a powerful tool for socially vulnerable groups (Van der Veken, Lauwerier, & Willems, 2020). Healthcare professionals, social workers, and nutritional experts can initiate drives for healthy living among underserved communities in Saudi Arabia.

Due to the inequalities between men and women in Saudi Arabia, women cannot frequently seek medical services. Gender segregation is a social norm that cuts across all life aspects (Amin et al., 2020). For instance, incidents of women-only healthcare facilities strain the healthcare system, especially when most are understaffed. Telemedicine offers a viable alternative to addressing cases of segregation in these hospitals.

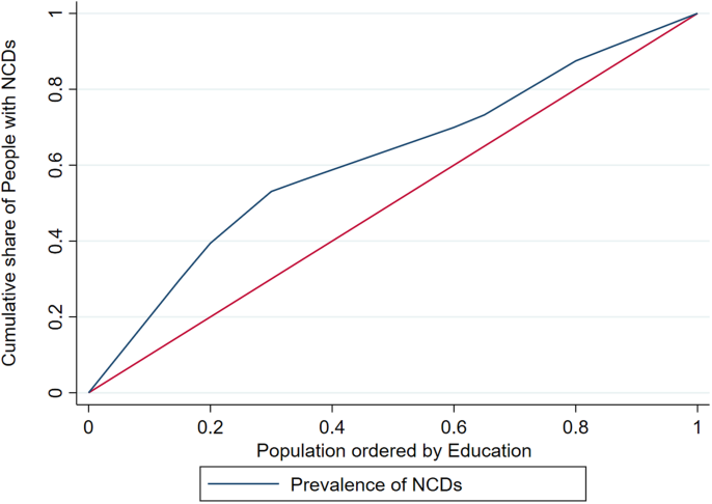

Varying social and economic factors play a significant role in vast healthcare inequalities. In Figure 3, the less educated are characterized by a disproportionate concentration of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as chronic illnesses and cardiovascular diseases. These diseases tend to negatively affect the health and well-being of an individual due to their long-term persistence in the body of an individual.

Figure 3: Socioeconomic determinants and inequalities in the spread of non-communicable diseases (Al-Hanawi, 2021).

A considerable disparity exists between insured and non-insured individuals. The study demonstrates that people living in urban areas, such as Riyadh, seek healthcare services often compared to people in rural areas (Al-Hanawi & Chirwa, 2021). Most people in urban areas enjoy hefty insurance premiums, while most people in rural areas settle for primary healthcare packages.

The limited knowledge of the causes and effects of CHD in areas such as Jeddah is associated with the constant increase in disease spread. Focusing on public health education programs can foster positive outcomes in these areas (Almalki et al., 2019). Knowledge and awareness about the individual risk factors for developing CHD can prevent the spread of preventable diseases and reduce associated mortalities. Even without adequate healthcare institutions, society must be equipped to overcome preventable diseases and avoid straining the existing healthcare facilities.

Coronary heart disease remains a considerable health hazard among middle-aged individuals in Saudi Arabia. Despite the prevalence of this disease, societal awareness regarding the underlying risk factors remains low. According to Albugami et al. (2020), this limited knowledge of the dangers of the disease can be attributed to the widespread CHD cases in the country. Additionally, since unhealthy lifestyles primarily cause the disease, its spread can be reduced with proper sensitization and awareness.

Prevalence of CHD in Saudi Arabia

Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) has been increasing gradually over the years, primarily due to the unhealthy social lifestyles of Saudi communities. Primarily, this increase can be attributed to changes in lifestyle, urbanization, and an aging population. According to Bugami, Rana, & Raneem (2019), out of 418 patients that underwent PCI between January 2015 and 2017, 92.4% being of Saudi origin, diabetes Mellitus was detected in 53.8%, hypertension in 82%, and dyslipidemia in 70.7% of the patients. This study indicates a widespread of highly preventable healthcare conditions linked to the country’s cultural and social dynamics.

CHD is a complex condition influenced by various factors, including genetic predisposition, lifestyle choices, socioeconomic status, and access to healthcare. The prevalence of CHD, thus, varies across different regions and population groups within Saudi Arabia. A significant disparity exists between people living in the countryside and urban areas (Al-Hanawi & Chirwa, 2021). These disparities can be attributed to the variation in the distribution of healthcare amenities in the country.

CHD accounted for a substantial proportion of all deaths in the country, highlighting the importance of addressing CHD as a public health priority. However, specific prevalence rates for CHD might vary due to differences in data collection methodologies, sample sizes, and timeframes. Given the dynamic nature of health data, Heart Failure (HF) is the leading cause of death among the Saudi people, with the probability of dying from the cardiovascular disease of individuals aged between 30 and 70 years is 20.9% (Alharbi et al., 2022). The significant age bracket affected by lifestyle diseases demonstrates that the Saudi culture contributes to the challenge.

CHD accounts for a substantial proportion of all deaths in the country. According to the most recent data published in 2020, the number of CHD deaths was 39,037, constituting 29.13% of the total deaths recorded by WHO (Saudi Arabia, 2020). As such, Saudi Arabia ranked position 29 globally, highlighting the seriousness of the disease in the country. Health inequalities in Saudi Arabia are not evenly distributed, such that some regions experience higher rates of CHD. These disparities can be attributed to the variation in the access to healthcare facilities and resources that may differ across regions, leading to variations in health outcomes. The burden of CHD risk factors is significantly high in the Middle Eastern region, including Saudi Arabia (Almalki et al., 2019). Further, social factors play a considerable role in the prevalence of this disease. These factors range from communal celebrations during religious events to the vast cuisine in most areas nationwide.

Socioeconomic factors exhibit a significant role in health disparities in Saudi Arabia. Low-income individuals experience limited access to quality healthcare, leading to delayed diagnosis and treatment for CHD. Low-income earners, especially in rural areas, fail to seek medical services, causing their health to deteriorate. As opposed to employed individuals in urban setups, who have comprehensive insurance covers, most people in rural areas have neither resources to afford them quality healthcare, nor insurance covers that can cover their medical expenses (Al-Hanawi & Chirwa, 2021). Furthermore, they lack adequate exposure to proper and healthy lifestyles, which subjects them to various preventable diseases. The societal framework in the country lacks a reliable framework for upholding healthcare among most people.

Gender-based differences in health outcomes also exist in Saudi Arabia. Men have a higher prevalence of CHD than women, attributed to lifestyle habits, healthcare-seeking behaviors, and social norms. They have more income that affords them more high-calorie foods and fewer chores than women. Such incidents are high in urban areas where most people work in offices with little mobility (Al-Hanawi & Chirwa, 2021). The prevalence of these diseases has not been addressed, mainly due to the absence of focus on the need to prioritize healthy living and preventive medicine.

Unhealthy lifestyle choices, such as a sedentary lifestyle, poor diet, and tobacco use, contribute to the burden of CHD in Saudi Arabia. The quality and availability of healthcare services also affect health outcomes. Unequal distribution of healthcare resources and infrastructure can lead to disparities in access to timely and appropriate CHD treatment (Al-Hanawi & Chirwa, 2021). For instance, the absence of proper infrastructure in rural areas interferes with access to quality healthcare.

Government policies and political decisions can influence healthcare funding, infrastructure development, and social programs, which may exacerbate health disparities if not adequately addressed. The Saudi government has made little effort to promote equality in the distribution of healthcare services in the country. Fewer healthcare institutions in the countryside are enough proof that the government has not put adequate effort into providing healthcare services to all people equally (Al-Hanawi & Chirwa, 2021). The government must sensitize the masses to avoid incidents cases of disparities in the provision of healthcare across the country. Further, the government must initiate more studies and evidence-based research to understand the exact healthcare situation in the country.

Are Differences in Outcome Unfair?

Health inequality and inequity in Saudi Arabia related to Coronary Heart Disease are influenced by Disparities in prevalence rates, regional distribution, socioeconomic status, and gender. Healthcare inequality emanates from differences in healthcare outcomes between population groups. These disparities are based on differences in socioeconomic status, gender, and geographical location. The differences are weighed based on mortalities, known difficulties in healthcare access, and morbidities. For instance, access to quality healthcare is difficult in the rural areas of Saudi Arabia compared to urban areas (Amin et al., 2020). The working class enjoys proper and high-quality services in the most advanced healthcare facilities compared to the unemployed individuals in the countryside.

Healthcare inequity determines whether the differences are avoidable, unjustified, or unnecessary. Inequity provides that certain social groups are disadvantaged when enjoying quality healthcare services and opportunities. For instance, uninsured individuals with little or no income are unlikely to receive quality healthcare in advanced healthcare facilities in Riyadh. Additionally, individuals with good insurance and finances are unlikely to receive quality healthcare in some marginalized areas with few or no hospitals.

The Saudi healthcare system is unfair to the people in remote areas where infrastructure and other facilities are underdeveloped or absent. According to Alshammari (2019), rural areas are characterized by a lack of awareness and exposure to information, which interferes with the accessibility of quality healthcare. Having fewer healthcare institutions in rural areas relative to the populations indicates that the current distribution of resources to curb healthcare challenges among the masses can be termed unfair to those in these areas. Assessing the role of structural factors, access to healthcare, social determinants of health, gender bias, and government policies can help determine whether the underlying differences are unfair. Addressing these issues can promote health equity and equal opportunity for achieving desirable health outcomes.

Societal Influences on the Coronary Heart Disease

Various societal norms and cultural practices influence Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabian cuisine is known for its rich and flavorful dishes, often high in fats, sugars, and salt. Traditional meals such as Kabsa, Mandi, and various sweets are commonly consumed, contributing to unhealthy eating habits. Overconsumption of calorie-dense foods can lead to obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, all risk factors for CHD (Younossi, Corey, & Lim, 2021). With little consciousness of healthy diets, most people gradually contract lifestyle diseases.

Rapid urbanization and modernization have led to increased sedentary lifestyles in Saudi Arabia. Many people spend long hours at work or in front of screens, leading to reduced physical activity. Lack of regular exercise causes weight gain, increased blood pressure, and the developing CHD (Younossi, Corey, & Lim, 2021). The underlying cultural framework does not provide significant motivation to encourage healthy lifestyles.

Smoking tobacco is a common societal practice in Saudi Arabia, especially among men. It is a significant risk factor for CHD that leads to plaque build-up in the arteries, reducing blood flow to the heart. The social influence of peers and the desire to relieve stress have been commonly reported as the primary reasons for smoking (Alasqah, Mahmud, East, & Usher, 2019). Turning smoking into a social undertaking increases the number of smokers, which increases health risks for many people. Shisha smoking is an everyday social activity in Saudi Arabia, especially among young adults. It is often perceived as less harmful than cigarette smoking, but it still poses health risks, including an increased risk of CHD.

Uncontrolled diabetes can damage blood vessels and increase the risk of developing CHD. Cases of diabetes have increased in recent years, with a ten-fold increase over the past thirty years (Robert & Al Dawish, 2020). This spread has occurred majorly due to unhealthy lifestyles inculcated in the societal structures of Saudi Arabians.

Traditional gender roles in Saudi Arabia considerably impact health behaviors and contribute to stress. Men might face work-related pressures and expectations to provide for their families, while women may experience stress due to balancing family and societal responsibilities. Vast cases of chronic stress have been linked to CHD (Sumner, Cleveland, Chen, & Gradus, 2023). The prevalence of stress in the country has increased due to the disintegration of social ties that enabled most people to solve problems communally. The current urban setup has reduced cohabitation, which has isolated most people, increasing their financial and psychological burdens. Access to sports facilities and recreational spaces can be limited in certain regions. Introducing this culture has become complicated since the norm has never been adopted.

Societal norms and beliefs about health and illness can influence healthcare-seeking behaviors. Some individuals may delay seeking medical attention, leading to late diagnosis and management of CHD (Younossi, Corey, & Lim, 2021). The social groups in Saudi Arabia fail to emphasize the need to seek healthcare services such that most people experience quality social ties when undertaking social activities during meals. At the same time, the same initiative does not spread to seeking healthcare services. Consequently, most people seek interventions when their conditions advance.

Measures that might reduce the Prevalence of Health Challenges

Addressing the societal norms contributing to CHD in Saudi Arabia can significantly reduce cardiovascular complications in its population. Implementing comprehensive public health campaigns to raise awareness about CHD risk factors, healthy eating, and the importance of physical activity can shift the current challenges in the country. Tailoring health promotion messages to align with Saudi Arabian cultural norms and values could increase the likelihood of adoption (Younossi, Corey, & Lim, 2021). Encouraging employers to promote employee wellness by offering physical activity programs and smoking cessation support can reduce negligence toward healthy living. Implementing policies that regulate tobacco use, banning social smoking of shisha, establishing drives to promote healthy eating, and improving access to healthcare facilities can reduce widespread heart-related problems. Involving local communities in health promotion efforts can help create a sense of ownership and empowerment.

The Societal influences on CHD

Societal influences significantly shape the prevalence and impact of Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) in Saudi Arabia. These influences are interconnected with cultural norms, lifestyle habits, and healthcare-seeking behaviors. Rapid urbanization and modernization in Saudi Arabia have led to increased sedentary lifestyles. Many individuals spend extended periods sitting, whether at work, during leisure activities, or due to limited opportunities for physical activity. Lack of regular exercise is a risk factor for CHD (Elagizi et al., 2020). In most fun activities, such as football, the Arabic society participates by watching, with only a few young people participating in physically engaging activities.

Traditional Saudi Arabian cuisine is rich in fats, sugars, and salts, which can contribute to obesity, high blood pressure, and other risk factors for CHD. Adopting Western dietary patterns, characterized by processed and fast foods, has further exacerbated this issue. Smoking is a prevalent societal issue in Saudi Arabia, particularly among men. Tobacco use is a significant risk factor for CHD, increasing the likelihood of developing heart-related problems (Gupta et al., 2019). Little efforts to sensitize the masses on the need to abstain from tobacco due to the health risks it exhibits upon them remain insignificant.

Some cultural practices, such as large communal meals with rich dishes and the use of hookah (shisha), contribute to unhealthy eating patterns and tobacco use, which increases the risk of CHD. According to Darawshy (2021), tobacco smoking is associated with stiffness of the arteries and the ultimate development of coronary heart disease. Embracing a culture that encourages community smoking increases the prevalence of CHD.

Traditional gender roles and expectations can influence health behaviors. For instance, men may engage in riskier behaviors or work in environments that increase stress and exposure to harmful substances, while women’s roles might involve less physical activity (Younossi, Corey, & Lim, 2021). Lack of awareness about risk factors, symptoms, and preventive measures may lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment. Modern living, work-related pressures, and family responsibilities can lead to high-stress levels associated with an increased risk of CHD.

Family plays a vital role in Saudi society but can also influence health behaviors. If unhealthy habits are prevalent within families, they can be perpetuated across generations. The availability and accessibility of healthcare facilities, preventive programs, and resources for managing CHD can be influenced by societal priorities and government policies. Community-based initiatives are fundamental in establishing measures to address health issues affecting society efficiently (Alrebish, 2020). The social dynamics seem not to prioritize the spread of healthcare facilities. Thus, healthcare promotion is a secondary undertaking in most areas of the country.

Addressing societal influences on CHD in Saudi Arabia must involve multiple stakeholders, such as healthcare providers, government agencies, educational institutions, and community organizations. Public health campaigns, policy initiatives, and community-based interventions can help promote healthier lifestyles, raise awareness, and improve healthcare access (Gosadi, 2019). Cultural sensitivity and adaptation among the majority can ensure that interventions resonate with Saudi Arabian society and effectively address the country’s widespread health problems associated with CHD.

Saudi Arabian Policies that Address Existing Inequalities

Saudi Arabia has established various policies and initiatives to address inequalities in healthcare and improve overall health outcomes for its people. Mandatory health insurance for all citizens has made it possible for everyone to afford and access healthcare regardless of their social and economic statuses. Additionally, visa fees for immigrants include insurance to cover their medical requirements once they enter the country (Pyvovar & Bandar, 2020). While the country seeks to improve healthcare service delivery, this move ensures that all its citizens receive treatment from government hospitals.

The government has expanded primary healthcare facilities in underserved regions around the country. Although this move has increased the correlation of primary healthcare centers to the population in Tabouk, Jeddah, and the Northern region, the ratio remains low in Riyadh, Al-Ahsa, and the Eastern region, leading to an overall decrease from 0.72 to 0.62 (Al-Sheddi et al., 2023). Nevertheless, the government’s response to the rising healthcare demand points in the right direction and could improve significantly. One of the country’s vision strategies is to transform the healthcare sector positively to avail healthcare services to all its citizens.

Although Saudi Arabia has laid out strategies to transform its healthcare sector among other sectors, the implementation progress remains small. Vision 2030, which was aimed at garnering political support, has not yet been turned into action to improve population health. Sustainable healthcare is yet to be accomplished; however, strengthening human resources in healthcare and efficient use of resources through good governance, accountability, and transparency could accelerate the country’s quest for the vision (Rahman & Al-Borie, 2021). The prevalence of Vision 2030 provides considerable room through which the people can seek accountability from the government for the attainment of underlying goals and strategies.

Policy Recommendation

Saudi Arabia is trailing in its healthcare system in regard to scope, structure, and workforce capacity. The country’s healthcare system experiences inequitable healthcare access and safe service delivery, the spread of chronic diseases, an ineffective information system, and issues of management and leadership (Asmri et al., 2020). The country may need to adopt Universal Health Coverage (UHC) to address widespread inequalities. This system has been successfully implemented in countries like the United Kingdom, Japan, and Canada.

Improving the current healthcare system by enhancing employee motivation will reduce the turnover of nurses in the county’s healthcare sector. Strict government policies have been associated with high turnover, such as the fees on the nurses’ dependents, understaffing in most hospitals, and the high cost of living in Saudi Arabia (Alshareef et al., 2020). Establishing favorable healthcare conditions for nurses and other healthcare workers will incentivize the immigration of competent healthcare workers, which will help address the current shortage in primary healthcare facilities.

A comprehensive and multi-faceted approach addressing various health determinants must be adopted to reduce inequalities in the healthcare sector in Saudi Arabia. Implementing a UHC system will enhance access to essential healthcare services by reducing widespread inequalities in the healthcare sector. Implementing targeted health interventions focusing on vulnerable populations will help address specific health issues affecting underserved regions. Expanding primary healthcare centers, increasing the number of healthcare centers in these regions, and upholding preventive care reduce the rate of infections across populations. According to Razzak, Imran, and Xu (2020), preventive healthcare is fundamental in addressing a wide range of infections and detecting diseases early, reducing the burden on the healthcare system. Promoting social healthcare drives to sensitize the masses on regular checkups provides a desirable framework for involving all people in preventing potential diseases.

Despite attempts to increase primary healthcare centers in Saudi Arabia, the population growth rate remains higher. Sensitization of the people and using telemedicine can play a considerable role in availing healthcare services in rural areas, reducing the underlying disparities. Amin et al. (2020) recommend using telemedicine to reduce disparities between urban and rural areas. The major challenge regarding the utilization of telemedicine entails the absence of proper network connectivity in remote areas, mainly the southern region. Furthermore, most people in these areas lack adequate knowledge of internet-based systems (Alavudeen et al., 2021). While telemedicine could transform the distribution of healthcare services in all places around the country, the government must connect all the potential areas with reliable internet. Enhancing literacy levels will further increase the assimilation rate of services from telemedicine systems on the Internet.

Conclusion

Saudi Arabia faces significant healthcare inequalities from a complex interplay of societal norms, political factors, and healthcare system challenges. CHD prevalence in the country highlights the urgency of addressing disparities to improve overall health outcomes. So far, the government has established policies to enhance healthcare access and quality; however, a comprehensive approach is needed to avail healthcare services to all people across the country. Implementing Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and targeted health interventions can reduce healthcare disparities and promote health equity. Further, collaboration among policymakers, healthcare providers, and communities can lead to a fairer and more inclusive healthcare system, granting equal access to the people. Prioritizing health equity will enable Saudi Arabia to create a healthier nation and measure up to the underlying international standards.

References

Alasqah, I., Mahmud, I., East, L., & Usher, K. (2019). A systematic review of the prevalence and risk factors of smoking among Saudi adolescents. Saudi Medical Journal, 40(9), 867.

Alavudeen, S. S., Easwaran, V., Mir, J. I., Shahrani, S. M., Aseeri, A. A., Khan, N. A., … & Asiri, A. A. (2021). The influence of COVID-19 related psychological and demographic variables on the effectiveness of e-learning among healthcare students in the southern region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal, 29(7), 775-780.

Albugami, S., Al-Husayni, F., Bakhsh, L., Alhameed, F., Alsulami, A., Abumelha, K., … & Balubaid, M. M. (2020). The perception of coronary artery disease and cardiac catheterization in Saudi Arabia: “What the public know”. Cureus, 12(1).

Al-Hanawi, M. K. (2021). Decomposition of inequalities in out-of-pocket health expenditure burden in Saudi Arabia. Social Science & Medicine, 286, 114322.

Al-Hanawi, M. K. (2021). Socioeconomic determinants and inequalities in the prevalence of non-communicable diseases in Saudi Arabia. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 1-13.

Al-Hanawi, M. K., & Chirwa, G. C. (2021). Economic analysis of inequality in preventive health checkups uptake in saudi arabia. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 745356.

Alharbi, M. F. (2018). An analysis of the Saudi healthcare system’s readiness to change in the context of the Saudi National Healthcare Plan in Vision 2030. International Journal of Health Sciences, 12(3), 83.

Almalki, M. A., AlJishi, M. N., Khayat, M. A., Bokhari, H. F., Subki, A. H., Alzahrani, A. M., & Alhejily, W. A. (2019). Population awareness of coronary artery disease risk factors in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. International Journal of General Medicine, 63-70.

Alrebish, S. A., Taha, M. H., Ahmed, M. H., & Abdalla, M. E. (2020). Commitment towards a better future for medical education in Saudi Arabia: the efforts of the college of medicine at Qassim University to become socially accountable. Medical Education Online, 25(1), 1710328.

Alshammari, F. (2019). Perceptions, preferences and experiences of telemedicine among users of information and communication technology in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Health Informatics in Developing Countries, 13(1).

Alshareef, A. G., Wraith, D., Dingle, K., & Mays, J. (2020). Identifying the factors influencing Saudi Arabian nurses’ turnover. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(5), 1030-1040.

Al-Sheddi, A., Kamel, S., Almeshal, A. S., Assiri, A. M., Al-sheddi, A., & Kamel Jr, S. (2023). Distribution of Primary Healthcare Centers Between 2017 and 2021 Across Saudi Arabia. Cureus, 15(7).

Amin, J., Siddiqui, A. A., Al-Oraibi, S., Alshammary, F., Amin, S., Abbas, T., & Alam, M. K. (2020). The potential and practice of telemedicine to empower patient-centered healthcare in Saudi Arabia. International Medical Journal, 27(2), 151-154.

Asmri, M. A., Almalki, M. J., Fitzgerald, G., & Clark, M. (2020). The public health care system and primary care services in Saudi Arabia: a system in transition. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 26(4), 468-476.

Bugami, S. A., Rana, B., & Raneem, H. (2019). Outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention among patients with coronary artery disease in Saudi Arabia (single center study). Journal of Cardiology and Current Research, 12, 55-58.

Darawshy, F., Rmeileh, A. A., Kuint, R., & Berkman, N. (2021). Waterpipe smoking: a review of pulmonary and health effects. European Respiratory Review, 30(160).

Elagizi, A., Kachur, S., Carbone, S., Lavie, C. J., & Blair, S. N. (2020). A review of obesity, physical activity, and cardiovascular disease. Current Obesity Reports, 9, 571-581.

Gosadi, I. M. (2019). National screening programs in Saudi Arabia: overview, outcomes, and effectiveness. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 12(5), 608-614.

Gupta, R., Gupta, S., Sharma, S., Sinha, D. N., & Mehrotra, R. (2019). Risk of coronary heart disease among smokeless tobacco users: results of systematic review and meta-analysis of global data. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 21(1), 25-31.

Khashoggi, B. F., & Murad, A. (2021). Use of 2SFCA method to identify and analyze spatial access disparities to healthcare in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Applied Sciences, 11(20), 9537.

Pyvovar, Y., & Bandar, N. (2020). Effectiveness, Risks and Prospects of Legal Regulation and Practical Functioning of Electronic Visas in Saudi Arabia and Ukraine. Journal of Politics & Law, 13, 101.

Rahman, R., & Al-Borie, H. M. (2021). Strengthening the Saudi Arabian healthcare system: role of vision 2030. International Journal of Healthcare Management, 14(4), 1483-1491.

Razzak, M. I., Imran, M., & Xu, G. (2020). Big data analytics for preventive medicine. Neural Computing and Applications, 32, 4417-4451.

Robert, A. A., & Al Dawish, M. A. (2020). The worrying trend of diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia: an urgent call to action. Current Diabetes Reviews, 16(3), 204-210.

Saudi Arabia: Coronary Heart Disease (2020). World Health Rankings. https://www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/saudi-arabia-coronary-heart-disease

Sumner, J. A., Cleveland, S., Chen, T., & Gradus, J. L. (2023). Psychological and biological mechanisms linking trauma with cardiovascular disease risk. Translational Psychiatry, 13(1), 25.

Tyrovolas, S., El Bcheraoui, C., Alghnam, S. A., Alhabib, K. F., Almadi, M. A. H., Al-Raddadi, R. M., … & Mokdad, A. H. (2020). The burden of disease in Saudi Arabia 1990–2017: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet Planetary Health, 4(5), e195-e208.

Van der Veken, K., Lauwerier, E., & Willems, S. J. (2020). How community sport programs may improve the health of vulnerable population groups: a program theory. International journal for equity in health, 19, 1-12.

Younossi, Z. M., Corey, K. E., & Lim, J. K. (2021). AGA clinical practice update on lifestyle modification using diet and exercise to achieve weight loss in the management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: expert review. Gastroenterology, 160(3), 912-918.

write

write