Shock is often challenging in pediatrics because it requires prompt and meticulous fluid management with frequent revaluation. Children in shock who are not managed appropriately will often quickly decompensate and develop cardiac arrest quite quickly. Therefore, most protocols, including the AHA PALS guidelines, recommend repeated boluses of 20mls/kg for children in shock until the symptoms resolve. In cases of cardiogenic shock and severe acute malnutrition, however, fluid overload and pulmonary edema can easily result if the fluid rehydration is not adequately monitored. There is conflicting evidence about patients with SAM being predisposed to myocardial dysfunction that may result in cardiogenic shock and pulmonary edema if fluids are given judiciously (Brent et al., 2019). As a result, many guidelines differ on how to adequately manage patients with severe acute malnutrition with signs of hypovolemic shock and more so when the shock is refractory.

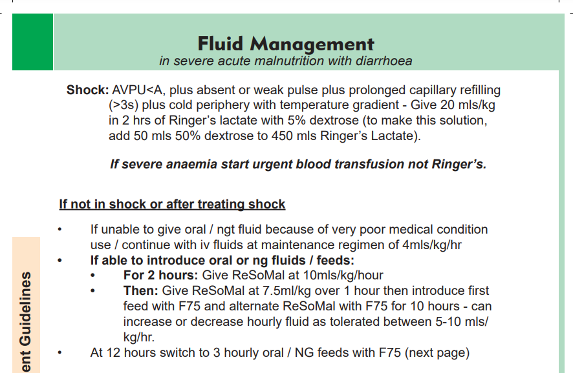

A 9-month-old child was admitted with signs of respiratory distress with bilateral crackles, tachypnea, hotness of body, reduced consciousness (AVPU- P), refusal to feed, with severe acute malnutrition (WHZ <3, MUAC of 11, and bilateral pedal edema). The baby had weak peripheral pulses, cold peripheries, temperature gradient, delayed capillary refill (4 seconds), and reduced level of consciousness (AVPU P). Because the baby had refused to breastfeed, I thought he was suggestive of hypovolemic shock, with septic shock being a differential. I used the Kenya Basic Pediatiec protocol guidelines to manage the shock. Although PALS AHA guidelines recommend giving boluses of 20ml/kg for hypovolemic shock until the symptoms of shock resolve, the Basic pediatric protocol (2022) in Kenya discourages these boluses in patients with severe acute malnutrition and instead recommends giving fluids 20mls/kg of RL with D5 over 2 hours and afterward using RESOMAL (Ministry of Health, 2022). While following this protocol, however, I encountered challenges. The symptoms of shock did not resolve as fast as I hoped. I thought the rate for the fluids was too slow. Resultantly, the infant died a short while later.

The WHO guidelines for managing hypovolemic shock in SAM differ notably from those in Kenya. First, instead of recommending 20mls/kg of fluids over 2 hours, it recommends 15mls/kg for one hour, possibly repeating the bolus in the second hour (World Health Organization, 1999). While the Kenya guidelines are silent about refractory shock, the WHO guidelines recommend blood transfusion if shock persists after two boluses (10mls/kg over 3 hours). Also, while the Kenyan guidelines recommend using RESOMAL after the initial intravenous fluids, the WHO guidelines recommend using ORS after the bolus. The WHO guidelines also recommend monitoring the pulse rate, hepatomegaly, respiratory rate, and urine output during resuscitation.

Even though the WHO guidelines seem more comprehensive, Kumar et al. (2023) argue that physiological evidence does not support the guidelines. Nonetheless, their study showed that the guidelines are effective in nonrefractory shock. In refractory shock, in addition to blood, the use of vasopressors such as adrenaline and dopamine has a mortality benefit. Surprisingly, a study comparing the WHO guidelines, which recommend fluids of 30ml/kg over 2 hours, to the India Academy of Pediatrics (IAR), where the fluids are given twice as first, showed a 40 to 60 percent improvement of symptoms within 12 hours when the IAR guidelines were used (Kumar et al., 2023). This finding supports my thought that the baby had better outcomes had we delivered the fluids faster.

Nevertheless, it is still important to acknowledge that septic or hypovolemic shock in SAM has a high mortality rate, regardless of the guidelines used in management. It is, therefore, important to have a good understanding of physiological and clinical management to determine the treatment plan that could be most beneficial to the patient. As doctors, it is important to consider the wide range of evidence available to help us make evidence-based decisions that will give our patients the best chance. Clinical judgment and decision-making, therefore, must be considered in the case of multiple conflicting pieces of evidence.

References

Brent, B., Obonyo, N., Akech, S., Shebbe, M., Mpoya, A., Mturi, N., Berkley, J.A., Tulloh, R.M. and Maitland, K., 2019. Assessment of myocardial function in Kenyan children With severe, acute malnutrition: the Cardiac Physiology in Malnutrition (CAPMAL) Study. JAMA Network Open, 2(3), pp.e191054-e191054.

Kumar, C., Manwatkar, S., Saroj, A. K., Singh, T. B., Rao, S. K., Saroj, D. K., & bali Singh, T. (2023). Effectiveness of the WHO Protocol for Managing Shock in Children With Severe Acute Malnutrition. Cureus, 15(9).

World Health Organization. (1999). Management of severe malnutrition: a manual for physicians and other senior health workers. World Health Organization.

Ministry of Health, 2022. Basic pediatric protocols for ages up to 5 years.

write

write