Introduction

Since the mid-1990s, China has been one of the major global benefactors of foreign direct investment (FDI). FDI is an essential source of foreign funds for China’s reform and development. Most FDI inflows into China come from multinational companies (MNCs) operating in other Asian countries. Close to 80 percent of total FDI inflows have come from MNCs operating in Hong Kong, the United States, and Japan, with smaller shares from Australia, France, Germany, and Britain (The World Bank, 2010). China has been a significant recipient country for FDI; it is currently ranked 8th among all countries receiving FDI globally (Tseng & Zebregs, 2002). Furthermore, China has witnessed a significant transformation since the market reforms of 1978. The Chinese government, which was greatly inspired by Communist ideas, realized that it needed to expand to world trade and become more capitalistic. In 2001, the government made a stated pledge by joining the World Trade Organization. The nation is becoming an economic powerhouse, with a GDP Growth rate averaging 9 percent per annum since 1981 and topping 10percent in the past few years. According to the World Bank, if this pace of growth persists, China will outpace the United States as the fastest growing economy in the coming years. China has adopted clear regulations to promote export processing FDI, and as a result, has established several economic sectors for international investors (Todaro & Smith, 2012). This gives China a distinct edge in FDI Inflow, and according to the UNCTAD (2002), China overtook the U.S. as one of the major global beneficiary of FDI for the first time in 2002 (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2004). The purpose of this paper is to assess how inward FDI has aided China’s economic growth during the reform period ranging from China’s GDP growth, development of local industries, export and imports, generation of jobs, competitive advantage, and acquisition of new technology

Growth of China’s GDP

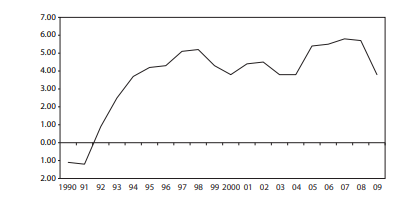

If contemporary China’s economy is a global key growth driver, FDI is the first mass of fuel that allows it to start spinning. Generally, the influence of inward FDI was seen at the macroeconomic, industrial, and microeconomic levels. In terms of GDP input and net export, inward FDI had a macroeconomic effect on local Real GDP. The proportion of foreign corporations in local gross value and total export can quantify the value of inward FDI to China’s GDP (Ek, 2007). According to projections, the typical input of inward FDI to China’s GDP is from about 3 to 6 percent (Li, 2013). Indirectly, inward FDI enhanced consumer spending through worker wages and other mechanisms (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Direct Contribution of FDI to China’s GDP (Li, 2013)

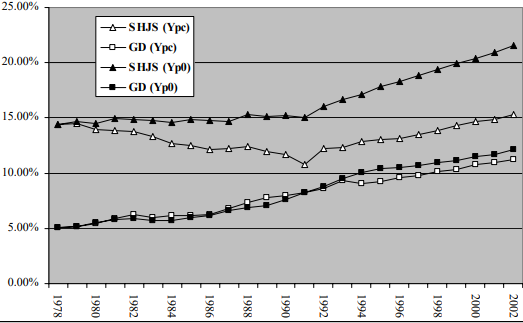

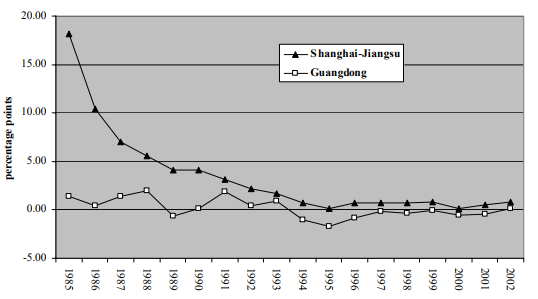

FDI has also contributed to GDP growth through increasing capital creation. In the 1990s, this factor is likely attributed around 0.4 percent to yearly GDP growth (Zebregs, 2001). The direct impact of FDI on GDP growth has been most substantial in provinces that have drawn the most international investors, ranging from over 4percent per annum in Guangdong to insignificant in most inland areas (Ek, 2007). (See figure 2). Through its positive impact on factor accumulation, FDI has also increased GDP improvement. According to empirical evidence, FDI increased TFP growth in China by about 2.5 percent per annum in the 1990s (Ek, 2007). This impact was shown to be highest in provinces that had attracted the most foreign direct investment. In total, FDI has provided approximately 3 percent to China’s projected GDP growth (Ek, 2007).

Figure 2: Proportion of GDP in steady-state prices, 1978-200(Lo, 2004)

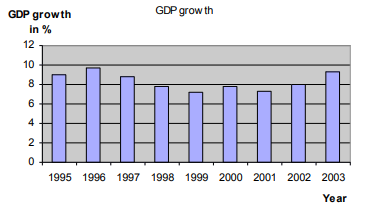

From the liberalization of the market in 1979 to the present, China has seen a lengthy era of continuous prosperity, with an extremely stable rate of GDP growth between 1995 through 2003. (Reuvid & Yong, 2005). Since 1978, when the Chinese market opened up, the economy has grown at an average annual rate of 9 percent, an unprecedented feat for any history of a country. China’s per capita contribution was around five folds more in 2004 as compared in 1978. (Ek, 2007). Growth had begun to get hot at this point, prompting the government to focus on bringing it back down to 9 percent. (Todaro & Smith, 2012). Although a 9 percent annual growth rate, China’s economy saw a significant drop in GDP from the mid-1990s until the end of the 20th century (Ek, 2007). As shown in Figure 2, China’s GDP growth slowed from 9.8 percent in 1996 to 7.3 percent in 1999.

Figure 3: China’s GDP increased from 1995 to 2003.(Ek, 2007)

Rapid Development of Industries, exports, and imports

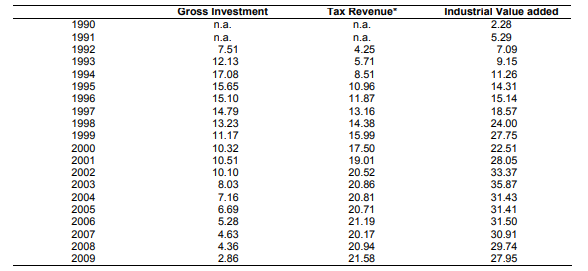

In addition to contributing to GDP, inward FDI also made a significant contribution to tax income and industrial expansion in China. In 2009, foreign-invested firms accounted for about 21.58 percent of total tax receipts (Wang et al., 2010). In 2009, foreign-invested businesses provided 27.95 percent of total industrial value added (Table 1). As a result, multiple industries emerged in China due to inward FDI, including home appliances, foodstuffs, and machinery manufacture (Li, 2013). Not only has the home appliances sector evolved, but it has also gained an edge over its competitors in the worldwide market.

Table 1: Input of FDI to China’s Gross Investment, Tax Income, and Industrial Value Added (Wang et al., 2010)

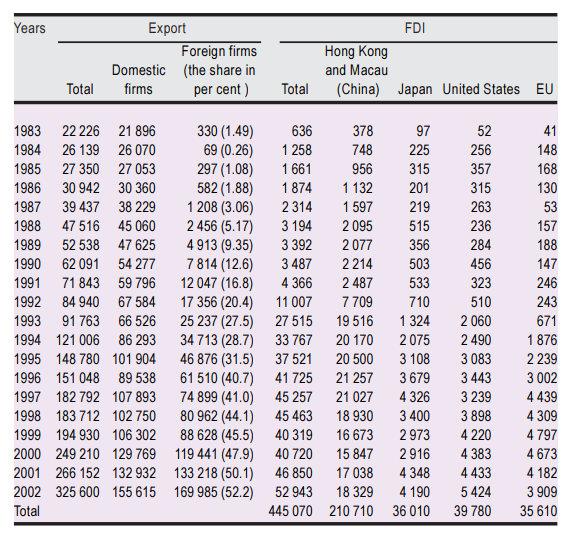

International firms significantly improved local firms’ shipments in China by providing investment opportunities, but they can also have indirect impacts that boost their export potential (UNCTAD, 2002). (See table 2). Spill-overs may occur, for instance, due to the creation of relationships between local enterprises and Transnational corporations (TNCs) as suppliers and partners. These ties open up channels for the transmission of information regarding technology and international market situations. Furthermore, by copying TNCs, local businesses understood how to thrive in international marketplaces (Wang et al., 2010). Marketing skills and expertise are passed back to the Chinese home business in Sino-foreign joint ventures. TNCs also educate native personnel in export marketing and international market knowledge, which local enterprises might gain by recruiting these TNC staff.

Table 2: China’s export market and inward FDI, 1983-2002 (Millions of dollars) (Wang et al., 2010)

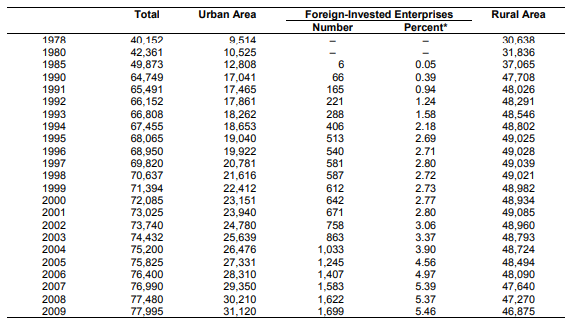

Opportunities for Employment Creation

Among the most noticeable effects of FDI in China has been the generation of employment possibilities, either directly or indirectly (Dunning, 1988). Foreign-invested firms improved labor productivity in China, transforming unskilled labor into skilled workers. This input can be categorized as investing in human capital at the macroeconomic scale and labor skill enhancement at the microeconomic level. Furthermore, while inward FDI contributes to export, it contributes relatively little to employment in China, with only 5.46 percent of workers in metropolitan areas employed by foreign-invested businesses (Dunning, 1988). This proportion is in line with the share in GDP. Due to their increased productivity, we can expect foreign-invested firms to make a relatively limited addition to employment in China (See table 3).

Table 3: Employment of Foreign-invested Enterprises (Dunning, 1988)

Focusing on the direct consequences, foreign-funded enterprises (FFEs) in city environments was four-folds between 1991 to 1999, bringing the total number to 6 million people, equivalent to 3 percent of all urban employment in China (Dunning, 1988). This has been especially significant in easing the effects of continuing state-owned firm reforms on unemployment. FFEs are especially substantial employers in the coastal areas, employing nearly 10 percent of Guangdong’s urban population. As of 1999 (Dunning, 1988), Shanghai, Fujian, and Tianjin were the three largest cities in China. (See figure 4).

Figure 4: Industry profit margins before taxes: comparisons to the state average, 1985-2002(Lo, 2004)

Creation of Highly Competitive and Dynamic Manufacturing Sectors

For exports, FDI has created a highly competitive and vibrant industrial sector. Since 1978, China’s commerce has grown for more than four times the rate of global trade, and China’s value of international trade has four-folds from 0.9 percent in 1978 to 3.7 percent in 2000, a feat that no other nation has achieved (Lardy, 2000). FFEs were crucial in achieving this goal. FFEs increased their proportion of exports from one percent to 45 percent between 1985 and 1999, accounting for half of total exportation and one-third of importation during that time (see table 2). FFEs were particularly important in the export of services; their exports rose from 8 percent to 22 percent (Dunning, 1988).

Domestic enterprises usually rival foreign enterprises might improve their production methods by studying and learning from MNCs’ advanced technology (Crespo & Fontoura, 2007; Zhang, 2001). Intense competition from MNCs may drive local businesses to enhance and upgrade their technologies to stay competitive. The results show that the total profit rates of domestic firms started to decline after 1995 and reached the bottom during 2000. FPEs brought new standard for-profit rates in China’s manufacturing industry (Dunning, 1988). Foreign companies have had above-average profit rates since their entry. The pre-tax profits of these FPEs were higher than those of UFEs or NMFs after they entered the China market, and they contributed to improving these sectors’ performance (see figure 4).

Access To New and Advanced Technologies

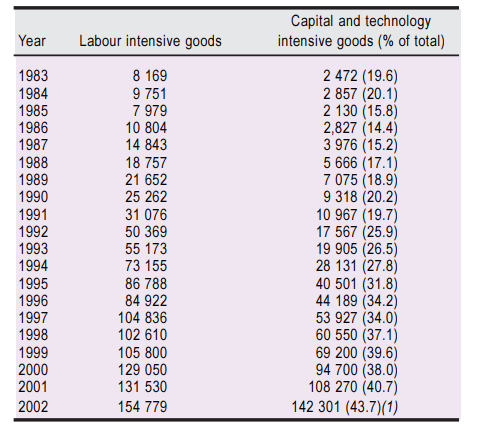

Technology spill-over from importation, fairs and exhibitions, and inward FDI is another benefit of inward FDI. Directly through the development of Foreign Funded Enterprises (FFEs) and indirectly through positive spill-over effects from FFEs to local firms, FDI has led to GDP growth (Wang et al., 2010). In China’s economy, FFEs are the most active and effective enterprises. During the years 1994 to 1997, the revenue of FFEs in the manufacturing industry grew at four folds the pace of other industrial firms, and their employment growth was nearly double that of public sector entities. Furthermore, empirical studies have indicated that the existence of FFEs appears to have boosted domestic businesses, both in terms of higher revenues and favorable spill-overs (Zebregs, 2001). When FFEs incorporate new technologies and managerial abilities, the latter occurs. These externalities have grown in importance as more connections between FFEs and domestic firms developed in the 1990s (See table 4).

Table 4: China’s Export Pattern, 1983-2002 (Millions of dollars) (Wang et al., 2010)

Transfer of technology must be helpful to the Chinese business community beyond the firm that acquires it first to generate externalities. China’s corporate sector’s technological capability is critical. According to evidence, the “technical gap” between local companies and foreign entrepreneurs must be comparatively small for FDI to have a more significant beneficial effect on productivity than domestic investment (Wang et al., 2010). Local firms are unlikely to assimilate foreign innovations conveyed via MNCs when considerable gaps exist or China’s fundamental technological level is low.

New products are introduced to China’s market by international investors. This is the essential information for Chinese firms at the start of their reform and opening process. This information helps the Chinese firms be more competitive globally by providing knowledge about the whole process of the industry. An increase in exports allows China to develop a new market. FDI has led new products and services to China’s market. Inward FDI is also associated with innovation in local firms and may, therefore, influence their technological development (Wang et al., 2010). Long-term national comparative studies have shown that TNCs are significantly more innovative than their domestic rivals (Lo, 2004). MNCs have provided and developed new skills to execute the technologies alongside the latest technologies (Potterie & Lichtenberg, 2001). New ideas brought in by FDI also enhanced China’s store of ideas, stimulating innovation. Through new products, processes, and practices, FDI brought new technology previously used in China’s economies.

Conclusion

While further research is needed to fully flesh out the key findings from China’s FDI history, some preliminary conclusions can be formed. The impact of inward FDIs to Economic growth throughout the reform period was assessed in this article. Inward FDI has contributed to China’s economy in terms of GDP growth, development of local industries, export and imports, generation of jobs, gaining competitive advantage, and transfer of advanced technology. The evidence collected indicated that inward FDI has been responsible for the most significant contribution to China’s growth since the reforms of 1978. It is still imperative to create jobs, improve living standards, and enhance competitiveness. The implication of China’s development by FDI is more on the industrial sectors’ growth. The contribution of FDI to China’s economy in terms of service sector growth is lower than other sectors. This impact will be more fruitful to China in the future because of the ever-growing mature industrial sectors. The analysis results are robust because those methods were used for the measurement of contribution.

References

Crespo, N., & Fontoura, M. P. (2007). Determinant factors of FDI spill-overs: What do we really know? World Development, 35(3), 410–425

Dunning, J.H. (1988). The investment development cycle and third world multinationals. Transnational Corporations and Economic Development, 3, 135-166.

Economist Intelligence Unit (2004). Country Profile: China, Issues 1996 – 2005 Retrieved February 11, 2022 from: http://portal.eiu.com.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/index.asp?layout=displayIssue&publication_i d=140000814

Ek, A. (2007). The impact of FDI on economic growth: The case of China. Bachelor thesis within Economics. Jönköping International Business School

Lardy, N.R. (2000). Is China a ‘Closed’ Economy? Prepared Statement for a Public Hearing of the United States Trade Deficit Review Commission, the Brookings Institute, February, 24.

Li, Z. (2013). How foreign direct investment promotes development: The case of the People’s Republic of China’s inward and outward FDI. Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series, (304).

Lo, D. (2004). Assessing the Role of Foreign Direct Investment in China’s Economic Development: Macro Indicators and Insights from Sectoral-Regional Analyses.

Organization For Economic Co-Operation And Development (OECD). Foreign Direct Investment for Development. Maximizing Benefits, Minimizing Costs: Overview. (Paris: OECD Publications, 2002).

Potterie, B., & Lichtenberg, F. (2001). Does foreign direct investment transfer technology across borders? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 83(3), 490–497

Reuvid, J. & Yong, L. (2005). Doing Business with China – Fifth edition. GMB Publishing Ltd., London.

Todaro, M. P., & Smith, S. C. (2012). Economic development 11th edition.

Tseng, M.W., & Zebregs, M.H. (2002). Foreign direct investment in China: some lessons for other countries. International Monetary Fund.

The World Bank (2010). Foreign Direct Investment – the China story. World Bank Group. Retrieved February 11, 2022 from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2010/07/16/foreign-direct-investment-china-story

UNCTAD (2002). World Investment Report (New York and Geneva: United Nations).

Wang, C., Buckley, P. J., Clegg, J., & Kafouros, M. (2010). The impact of inward foreign direct investment on the nature and intensity of Chinese manufacturing exports. In Foreign direct investment, China and the world economy (pp. 270-283). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Zhang, K.H. (2001). How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth in China? Economics of transition, 9(3), 679-693.

Zebregs, H. (2001). Foreign Direct Investment and Output Growth in China. Forthcoming.

write

write