Abstract

Pay disparities between white employees and those of other ethnic groups imply that biasness may be a contributing factor. Nevertheless, there are two potential entrance points for prejudice to occur: during the hiring process and while working in the position. In the former, non-whites may have trouble breaking into high-paying fields, whereas in the latter, they can get the same kind of positions as whites but earn lower wages. As a result, discrimination takes the form of either lower pay or fewer available jobs. We utilize data from the British Labour Force Survey between 2012 and 2019 to demonstrate that there still exist pay disparities between whites and other ethnic groups. The analyzed data signifies that the pay disparity between whites and other ethnic group still exists. This is because, in 2019, there is still a gap in existence in 2012. However, the gap has indeed narrowed down as the years progressed.

Introduction

The ethnicity pay gap has been a phenomenon for a longest time. Therefore, this summary references other studies that have examined the ethnic wage gap. However, proponents of a segregating role point to data showing that other ethnic groups are more likely to be hired for lower-paying positions and get lower wages than whites(Adam et al., 2018). The racial disparity in income between white British employees and those of other ethnicities indicates discrimination. Discrimination, however, is not limited to the hiring process; it may also occur while an employee is already on the job. This essay’s primary goal is to demonstrate a pay disparity between whites and other ethnic groups. However, the essay also seeks to bring out the concept that the pay disparity gap has narrowed over the years from 2012 to 2019.

Literature Review

Recent decades have seen a tremendous shift in the demographics of the British workforce. From 2004 to 2019, the percentage of the workforce, including ethnic minorities, more than quadrupled, from 7% to 13% (Breach et al., 2017). However, as time has passed, more and more people have become aware of the salary and employment gaps between the White British population and other ethnic communities in the country. This has picked up steam in the past year, especially since the Black Lives Matter movement brought attention to the persistent discrimination that members of ethnic minorities face and sparked new calls for a comprehensive review of the obstacles these individuals face in the United Kingdom labour market. Whites earned a median hourly wage of £13.16 in 2020, whereas members of other racial and ethnic groups earned a median hourly wage of £13.37. For the first time since 2012, there is now a negative ethnicity pay difference (at -1.6%) (Bhopal, 2020).

Employees of other ethnic groups in the United Kingdom tend to earn less than white workers. According to the proposed research, discrimination is a factor both in the hiring process and inside a certain field. As a result, non-white people find employment in high-paying fields more challenging. Members of the opposite ethnic group may be given the same job opening (Brynin, 2012). Even yet, their salary has been cut. Therefore, one must choose between working and earning an income. Nonetheless, this research aims to learn about Britain’s job and social conditions by reviewing and summarizing the article “Britain’s Ethnic Gap in Pay.”

The primary argument is how different circumstances affect people’s chances of finding and keeping a job. Opportunities for advancement, taking into account relevant expertise and experience, as well as judgment, play a crucial role in the structure of the labour market (Clark and Nolan, 2021). This might be argued in two ways: fewer people from minority groups choose professions that pay highly, or those from minority groups get paid less for performing the same work. Such debatable issues as the article’s analysis are based on. Consequences of action are crucial, but occupational segregation occurs when certain groups are paid less for equivalent work.

The research article identifies numerous explanations for racial salary discrepancies in Britain. Essential aspects of the racial pay difference are described by the phenomenon of professional segregation, which zeroes down on any income inequality, whether it be exclusive or personal. As part of the research, we compare our findings to previous studies examining the gender wage gap in the workplace. According to the findings, a large salary disparity is an alarming sign of probable discrimination in the workplace (Appleby, 2018). The field environment consistently supports members of underrepresented groups, indicating that prejudice is uncommon. This further demonstrates the existence of an unwelcome wage disparity, perhaps caused by the concentration of certain ethnic groups in low-paying industries. The main approved form comprises; measuring the wage gap by subtracting the mean salary of numerous minorities from that of the white majority. Occupational mean salary estimates are also determined.

According to the paper’s main conclusions, the ethnic population distribution is different between the lower and higher socioeconomic classes. This explains occupational segregation has an impact that varies with the job at hand (Friedman et al., 2017). Although minorities tend to earn less than whites in the profession, on the whole, whites are more likely to be drawn to higher-paying positions. Since ethical minorities are more concentrated in either high- or low-paying fields, the salary difference may be traced back to these factors. This is due to personal causes, such as a lack of training or discrimination that prevents members of various minorities from obtaining well-paying employment.

All the attempts to close the gender pay gap are happening against the quickly changing environment, both in the working sector and in the surroundings of the various women companions’ everyday activities, which is the first proof of sluggish development in the alterations. Such unstable settings provide substantial roadblocks to advancement, making it very challenging to attain wage parity. Despite efforts and continued disparity, the gender wage gap is occurring in a non-linear fashion, including reversals. Individualism, secularism and consumerism are three universal standards that may work against the advancement of equitable pay (Pearson, 2014).

Another explanation for the lack of development is that ensuring everyone is paid fairly would need significant political will. Various governmental systems provide a wide range of employment possibilities meant to be filled by people of both sexes. Most workers, not just those in full-time and part-time positions, appear to be affected by the gender pay gap (Rubery and Koukiadaki, 2016). As many women are employed in low-paying fields, closing this gap is lengthy because women are more likely to seek part-time employment that seems to have lower pay than full-time compensation. Women, on average, spend more time away from their careers than men for reasons like pregnancy, childcare, and household chores. Part-time employment is more appealing to them since it allows them to juggle their many commitments better, but this also means they will advance more slowly in terms of salary.

Considering the disparate employment rates of sexes and ethnicities is crucial before analyzing the current wage discrepancies. According to data compiled from surveys of the working population, there is consistently wide variation in hourly wages across racial and ethnic groupings. The salary variety is related to the various abilities and expertise of the employees/jobs. Many methods have been used to measure and understand the causes of these wage disparities. A statistically predictive model is one such approach. Average differences in salary between workers of different professions make up what is known as the “pay gap (Atkinson et al., 2018).” According to a statistical analysis of the factors contributing to the racial and ethnic wage gap, there are commonalities among the various groups. Other variables somewhat reduce these racial disparities in wages. Furthermore, other ethnic minorities are thought to have better qualifying possibilities than white people who make decent average salaries.

Different research have all pointed to discrimination as the primary reason for the wage disparity. Some members of society have biased beliefs, and members of ethnic minorities are frequently blamed for being prejudiced. In addition, many businesses use candidates’ race/ethnicity as a stand-in for skill. One example is the stereotype that people of a certain ethnicity don’t put in as much effort as other ethnicities (Amadxarif et al., 2020). Therefore, when this policy is implemented, companies are more likely to treat members of the targeted ethnic group poorly or pay them less. This article’s analytic report aims to quantify the wage gap between members of Britain’s main ethnic minorities and white Britons. The gender of an individual is irrelevant for calculating compensation. Research has demonstrated that women are paid less than males, even if they both suffer from an ethnic minority. Additionally, ethnic groupings may be classified by; age, employment, and educational connection.

In comparison, workers from higher socioeconomic backgrounds, such as those in professional and managerial occupations, make up 37% of the workforce. This disparity accounts for nearly 10% of the class-based wage gap (Laurison and Friedman, 2016). Recent research reveals that employers judge aptitude based on characteristics of social class, despite the fact that there is a dearth of data on why people from low-class households cannot access the biggest, best-paying enterprises. Particularly, they look at things like how well put together you are, which is linked to coming from privileged families.

One of the key factors in determining wage disparity is the employer’s location.People who don’t live and work in a large city often have a lower standard of living than their urban peers. According to a study of the British workforce, people outside the capital city of London had median annual earnings of 13%-23% lower than those in London proper (Bhopal, 2020). As another example, there is a lack of information detailing why people with high levels of educational attainment are less likely to find employment in big metropolitan areas. Recent research has shown that professionals from middle-class families often lack the motivation and resources to take advantage of urban job markets.

Methodology

The data used was obtained from 2012 to 2019, featuring the Whites and the other ethnicities. The mean and median values were used in determining the difference between the Whites’s salary and the other ethnic groups salaries. Graphs were used to represent the data analysis in showing the distinct differences between the whites pay and the other ethic group pay.

Data Findings and Analysis

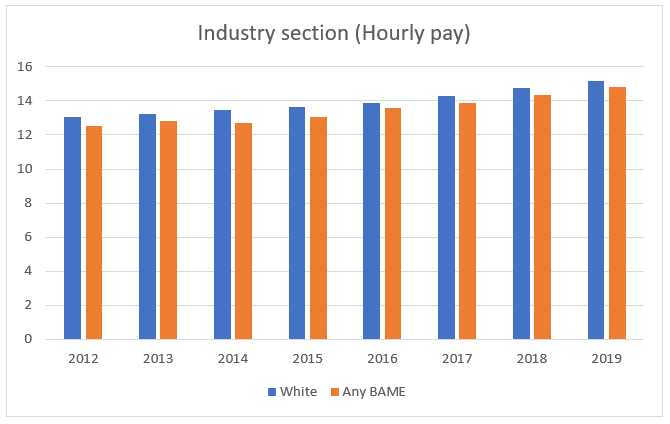

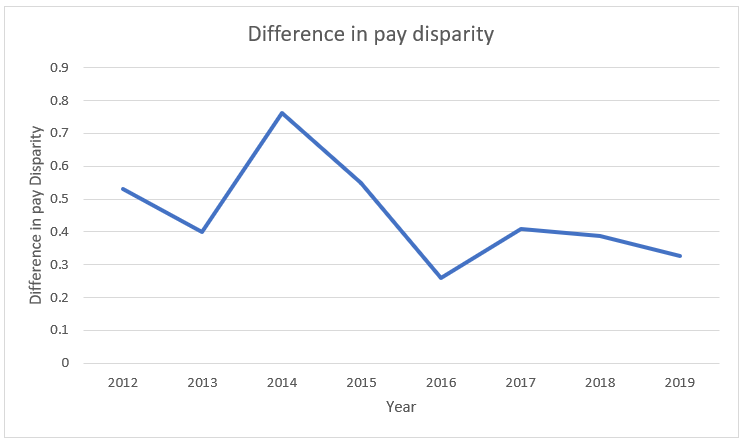

There is a significant difference between the hourly pay received by white employees and the rate received by the other ethic groups. In accordance to Appendix 1, the hourly pay rate for the whites is higher than the hourly pay rate for any other ethnic group from 2012 to 2019. As indicated by the graph, there is no year that the other ethnic groups pay has been higher than that of the white employees. This can be associated with discrimination in terms of race as well as ethnic groups. However, across the years, the pay disparity among the whites and the other ethnic groups has narrowed down. This is as shown in Appendix 2, where the difference has narrowed down over the years. For example, the table in appendix 2 shows that the pay disparity between whites and other ethnic groups in 2012 was 0.53, which has decreased to 0.33 in 2019. Therefore, it is true that the pay disparity has reduced as claimed.

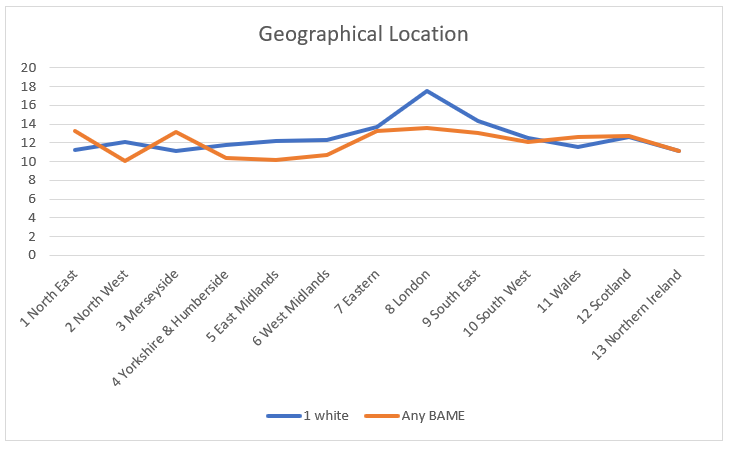

Geographical location is also an aspect contributing to pay disparities. For example, in Appendix 3, employees working in London receive a higher pay compared to the other geographical location. This includes for both male and female employees. On the other hand, Notherland Ireland employees receive the least pay compared to the other locations. Pay disparity due to geographical location can be due to differences in infrastructure between the countries. This can also be due to the political stability of the country, as well as the presence of policies which protect the employees from harsh treatment in their work places.

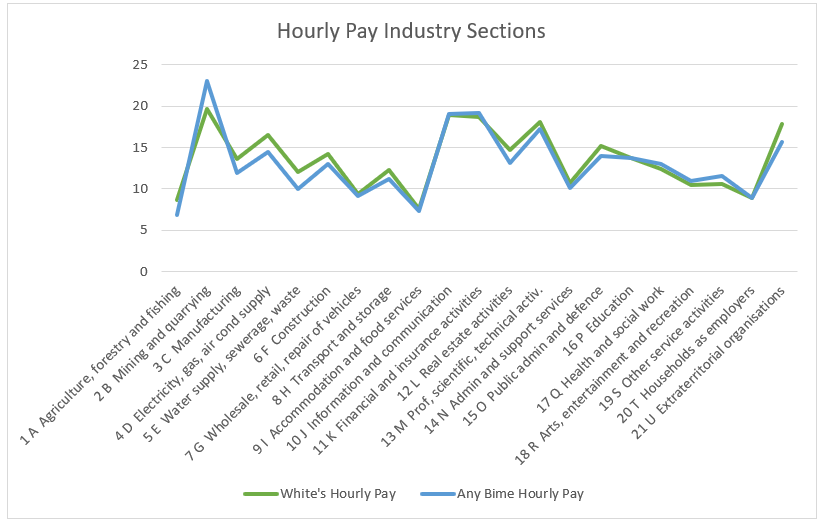

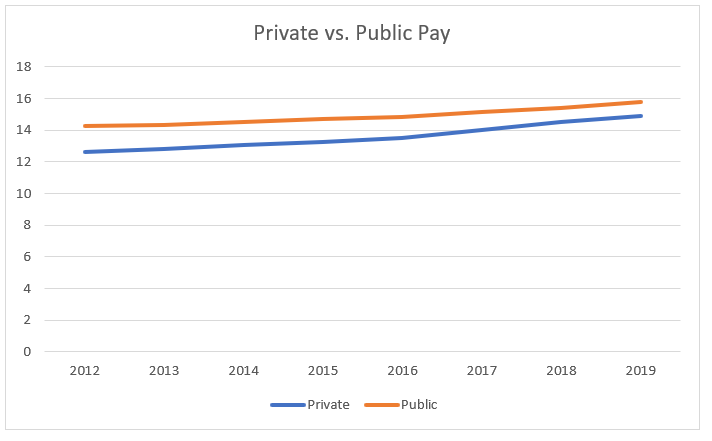

According to the industry sections in Appendix 4, the difference in the pay for the various industries does not depict a large difference between the two groups, the whites and the other ethnic groups. However, it is evident that the pay varies among the industry sectors. This is because different industires offer different job specifications and designs. However, according to Appendix 5, the pay difference between the private and the public sector is evident. In this case, the public sector offers better hourly pay compared to the private sector. The studies show a correlation between the ethnic pay difference with social isolation, although the racial pay gap is much less inside organizations. Therefore, isolation has strong negative qualities if minorities are overrepresented in the workplace (Adam et al. 2018). This examination of data from the United Kingdom shows significant discrepancies in the racial exchange of labour. This is meant to indicate that there are groups who do better than white Britons overall but pay a heavy price in terms of unemployment, professional standing, and income.

People on the rise are more likely to work in low-paying fields and are less likely to negotiate wage increases after they’re well established. Anxieties about fitting in and the likely concept of leaving class roots may explain why such persons do not have networks to link them to employment prospects; for example, they may not pursue promotions. When contrasted to people from more privileged backgrounds or in cases of homophily in job interviews and performance reviews, good mobiles may be at a disadvantage, as shown by research by Laurison and Friedman (2016).

Conclusion

There is strong evidence that ethnicity still plays a crucial role in determining the size of the existing pay gap in most nations, with minority groups from lower socioeconomic backgrounds experiencing greater disadvantages than their white counterparts. As indicated in the analysis, the difference in the pay disparity continues to narrow down as the years progress. However, the phenomenon of widening pay disparities is persistent and common in many civilizations that, at their core, include distinct socioeconomic strata. A person’s upbringing, level of education, and personal characteristics and habits might all have a role. The negative effects of pervasive discrimination may be mitigated if jurisdictions develop strategies to improve social fairness in access to resources and opportunities.

Recommendation

Giving employees an equal opportunity in workplaces is essential in improving their motivation. Employee motivation determines how effectively and efficiently an organization’s vision is achieved. Therefore, policies that support equality should be implemented to ensure that pay equality is attained. In addition, Employees should be encouraged to join workers union and organizations which fight for their rights in the workplace. This entails implementing an equal pay for work of equal value despite the employee’s race or ethinic group.

References

Adams, L., Luanaigh, A. N., Thomson, D., & Rossiter, H. (2018). Measuring and reporting on disability and ethnicity pay gaps. Equality and Human Rights Commission. The research report, 117. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3647190

Appleby, J. (2018). Ethnic pay gap among NHS doctors. BMJ, 362. https://www.bmj.com/content/362/bmj.k3586.full

Amadxarif, Z., Angeli, M., Haldane, A., & Zemaityte, G. (2020). Understanding pay gaps. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0950017012445095

Atkinson, H., Bardgett, S., Budd, A., Finn, M., Kissane, C., Qureshi, S., … & Sivasundaram, S. (2018). Race, ethnicity & equality in UK history: A report and resource for change. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/34577/1/RHS_race_report_EMBARGO_0001_18Oct.pdf

Bhopal, K. (2020). Gender, ethnicity and career progression in UK higher education: a case study analysis. Research Papers in Education, 35(6), 706-721. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02671522.2019.1615118

Breach, A., & Li, Y. (2017). Gender Pay Gap by Ethnicity in Britain. https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/files/52919431/Breach_and_Li_2017_Gender_Pay_Gap_by_Ethnicity_in_Britain.pdf

Brynin, M., & Güveli, A. (2012). Understanding the ethnic pay gap in Britain. Work, employment and society, 26(4), 574-587. (n.d.). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3828323

Clark, K., & Nolan, S. (2021). The changing distribution of the male ethnic wage gap in Great Britain. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3828323

Evans, T. (2020). Ethnicity Pay Gaps in Great Britain 2019. https://backup.ons.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/07/Ethnicity-pay-gaps-in-Great-Britain-2018.pdf (Evans, 2020)

Friedman, S., Laurison, D., & Macmillan, L. (2017). Social mobility, the class pay gap, and intergenerational worklessness: new insights from the Labor Force Survey. (n.d.).

Gough, O. (2018, March 26). Bridging the gender pay gap in the UK. Small Business UK. Retrieved January 16, 2022, from https://smallbusiness.co.uk/bridging-gender-pay-gap-2543319/

Healy, G., & Ahamed, M. M. (2019). Gender pay gap, voluntary interventions and recession: The case of the British financial services sector. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 57(2), 302-327. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/bjir.12448

Imogene, O. (2017). Beyond Expectations: Second-Generation Nigerians in the United States and Britain. Univ of California Press. (n.d.).

Khoreva, V. (2011). Gender pay gap and its perceptions. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/02610151111124969/full/html?mobileUi=0&fullSc=1&mbSc=1 (Khoreva, 2011)

Leping, K. O., & Toomet, O. (2008). Emerging ethnic wage gap: Estonia during political and economic transition. Journal of Comparative Economics, 36(4), 599-619. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0147596708000462 n

Longhi, S., & Brynin, M. (2017). The ethnicity pay gap. Equality and Human Rights Commission. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/research-report-108-the-ethnicity-pay-gap.pdf

Laurison, D., & Friedman, S. (2016). The class pays gap in higher professional and managerial occupations. American Sociological Review, 81(4), 668-695. (n.d.).

Laurison, D., Dow, D., & Chernoff, C. (2020). Class mobility and reproduction for black and white adults in the United States: A visualization. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 6, 237802312096095. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023120960959

Milner, S. (2021). Ethnicity pay gap: Why the UK needs mandatory reporting.

Pearson, R. (2014) “Gendered, Globalization and the Reproduction of Labor: Bringing the State Back In” in Rai, S. and Waylen, G. (eds) New Frontiers in Feminist Political Economy, Abingdon: Routledge, 19-42.

Pickett, K. E., & Wilkinson, R. G. (2015). Income inequality and health: a causal review. Social science & medicine, 128, 316-326. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953614008399

Platt, L. (2006). Pay gaps: the position of ethnic minority women and men. Manchester: Equal Opportunities Commission.

Rubery, J., & Koukiadaki, A. (2016). Closing the gender pay gap: A review of the issues, policy. International Labor Office. Retrieved January 16, 2022, from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—reports/—gender/documents/publication/wcms_540889.pdf

Smith, R. (2019). Gender pay gap in the UK: 2019. Statistical bulletin. London: Office for National Statistics. https://backup.ons.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/10/Gender-pay-gap-in-the-UK-2019.pdf

Wild, S. (2020). Gender Pay gap reporting: an introduction. COPD

Appendix 1: Industry section (Hourly Pay)

Appendix 2: Difference in Pay Disparity

| Year | The difference in pay disparity |

| 2012 | 0.531095898 |

| 2013 | 0.401013024 |

| 2014 | 0.762822226 |

| 2015 | 0.550031069 |

| 2016 | 0.260581627 |

| 2017 | 0.408493647 |

| 2018 | 0.388119773 |

| 2019 | 0.32615111 |

Appendix 3: Pay Disparities Based on Geographical Location

Appendix 4: Hourly pay per Industry section

Appendix 5: Private vs. Public Pay Disparity

write

write