Abstract

The study aims to investigate the factors that impact confidence and fluency in English speaking among TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) in China. The research seeks to find the chief issues these learners encounter besides exploring likely plans to stress their confidence and oral influence (Cheung, 2023).

The study uses a mixed-tactic approach, incorporating interviews and surveys, to gather data from TESOL learners at diverse stages of English proficiency. The outcomes of this research will give precious insights to TESOL educators and learners, contributing to improving English language teaching and learning in China.

Introduction

Practical communication skills and English fluency are increasingly significant in a globalized world. With the increasing demand for English language proficiency in China, TESOL programs have attained noticeable popularity among learners ambitious to become English language educators or improve their English proficiency (Lei & Lei, 2023).

Although, despite the exposure given and extensive training in these programs, numerous TESOL learners in China still need help developing their confidence and oral fluency in English speaking. The ability to speak confidently and fluently is critical to language learning as it permits persons to engage in meaningful conversation and express themselves efficiently.

Although many factors impact confidence and oral fluency, specifically in the context of TESOL learners in China, comprehending these factors is necessary for designing efficient interventions and strategies to enhance their speaking skills. This research aims to interrogate the factors affecting confidence in English speaking and fluency among TESOL learners in China. This study seeks to contribute to English language learning and teaching in China by finding the chief issues in improving confidence and oral fluency.

The importance of the research lingers on its likelihood to shed light on the unique matters faced by TESOL learners in China, as well as factors that obstruct the growth of confidence and oral fluency in English speaking. By gaining a more profound comprehension of these issues, curriculum designers and educators can tailor their interventions and approaches to better meet the needs of TESOL learners, ultimately improving language learning outcomes (Liu et al., 2023).

A mixed-methods tactic will be deployed to attain the research aims, combining interviews and surveys to gather data from TESOL learners at various proficiency levels. The study will give quantitative data on the participants, confidence levels, and self-perceived oral fluency. At the same time, the interview will offer valuable qualitative insights into their strategies, challenges, and encounters.

Literature Review

Description of fluency

There are numerous definitions of fluency in English. Fluency is the know-how to have the intent to pass the message without much hesitation and numerous pauses to cause incidence or barriers in communication; fluency is the character that gives speeches quality of being normal and natural. Incorporating native-like use of the rate of speaking, stress, intonation, rhythm, pausing, and use of interruptions and interjections.

In Hedge’s scope (1993), fluency is linked to linking speech units together without strain with facility or undue hesitation. These descriptions chiefly focus on the confidence and fluidness of producing speech without too much pause and hesitations. In this study, the author reveals that fluency is vital to learners’. Skill is likened to preciseness in the manner that concentrates learners on less hesitation, speed increase in speaking, and fewer pauses to stress learners’ confidence in speaking.

Fluency-grounded activities.

Conferring to Bailey (2003), fluency-grounded activities incorporate simulation, role-plays, jigsaw activities, and information gaps. According to other research, fluency-based acts incorporate communicative free-protection acts, repetition or rehearsal tasks, formulaic sequence use, discourse markers and lexical fillers, and consciousness-raising tasks.

Accuracy and fluency in speaking class

Various lesson stages in speaking classes stress both accuracy and fluency, fluency than accuracy and vice versa. The most significant thing is that the teachers must clearly focus on accuracy-based or fluency-based work to promote learners.

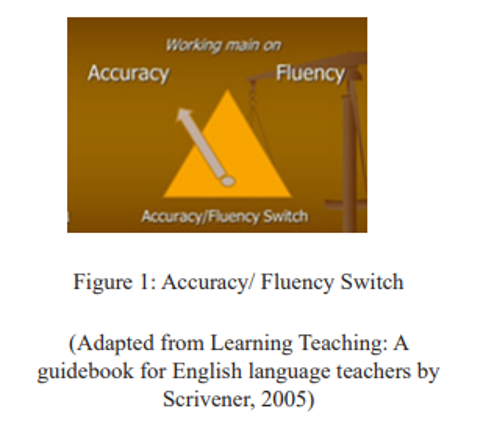

Conferring to the figure above, fluency/accuracy switch, it is correct that it will be a chief skill if every language teacher can regulate accuracy and fluency-based activities in speaking class. Fluency-grounded activities should represent one-quarter of class time to develop fluency in English speaking. Brumfit (1985) proposes a third of the total time for fluency activities from the start of the course, which should be raised during the course.

Issues manipulating fluency speaking skill

Affective Factors.

Concerning Ryan and Donyei (2015), their practical part is the noticeable impact on students’ language learning procedure. The affective factors link to attitudes, moods, and feeling to language learning, particularly to learning speaking, which this research assesses. In this article, the affective factors are seen as fear of making mistakes, self-confidence, shyness, and anxiety which are key impacts on fluency in speaking.

These affective influences are closely linked as aspects of opposing sides in speaking skills. Anxiety pervasively hinders the learning procedure as they worry about being stupid, wrong, or incomprehensible, which diminishes their speaking performance. Also, low willingness to communicate emanates from too much anxiety. Ultimately, it will have an undesirable impact on learners’ achievement in second-language classrooms.

Performance factors

The performance environment in speaking class also impacts the fluency degree of learners. Conferring to various researchers, diverse performance factors incorporate time pressure, planning time, and the support amount. It has been proposed that giving students more planning time before the task aids learners in producing more complex and fluent language.

Planning time also aids students in increasing grammatical complexity and fluency. Contrary to this, time pressure is the urgency of the speaking role that students ought to complete their performance which could raise the difficulty for it. Tran and Nguyen (2015) state that time pressure leads to undesirable performance in speaking. Also, teacher support and peer numbers make things less demanding, as presenting a subject with others is more straightforward than doing it alone.

Automation

The speaker’s automatic procedural skill is what is termed oral fluency. It is similar to a speed procedure. If it is recurrent in English learned, their fluency in speaking will be attained. Levelt (1989) explains a speech procedure that forms speech n daily life incorporating three phases: articulation, formulation, and conceptualization.

This procedural, psychological process implies that every vague notion is concise or conceptualized. The orator selects the relayed information grounded on their background information in the formulation phase, where lexis and grammar are arranged in correct syntax order along with chunk language and formulaic sequence, to the end phase- articulation, where speech organs come into play to produce sound.

However, speech fluency is triumphant; this process largely relies on articulation and, to a noticeable degree, on formulation and, to some extent, on conceptualization. If language starters need more automation, it will be problematic for them to produce fluent speech and pay attention. Nguyen (2015) states that fluency is a product of automation. Suppose learners are exposed to an English environment, such as teachers speaking English every time, English newspapers, English tapes, and English books for them to use. In that case, they can pick up the language unconsciously and naturally.

The suitable surroundings and a good atmosphere can also well-support learners to speak fluently, correctly, and actively. Learners can automatize to gain fluency in speaking if teachers continuously put learners under increased time pressure.

Methodology

Research participants

The study participants were 98 learners, 66 females and 32 males, haphazardly chosen from second-year non-majored learners of a University in China. Many of them have been learning English for close to 10 years. They are undertaking English courses in the first semester of the academic year.

This course involves a combined learning procedure whereby learners follow 40 periods of offline lessons and 35 periods of online. In the course’s units, they self-learn online five sections, writing skills, reading, listening, grammar, and vocabulary. In offline subjects, they typically concentrate on fluency-based and accuracy-grounded activities.

Before every offline lesson with their tutor in class, the learners must finish their online lesson at home. Besides, thirteen tutors mentoring English for first-year learners were also invited to undertake interviews in the study. There are 12 females and two males in this team of tutors, and they have 5 to 10 years of experience in tutoring English at the university.

Research procedures and instruments.

The research used a combined tactic design, which gathers both qualitative and quantitative data to explain and understand the research matter. The researchers selected a survey questionnaire as the chief instrument to collect quantitative data and then performed interviews to get in-depth qualitative data. Survey questionnaires by Nguyen and Tran, Marriam, Muhammad, and Ashiq 2011, were the source of adaptation for the survey questionnaire, mainly comprising eight questions. Also, some queries in this survey were formed grounded on theoretical know-how linked to the research topic analyzed in the literature review.

Initially, the questionnaire was piloted and administered to ten first-year, non-primary English learners of the university, who needed to be incorporated into the research to gain feedback on whether the research participants could comprehend the wording or instructions. After piloting and tryout, the questionnaire was reviewed by two experts in research (Musa, 2023).

The experts gave Oral explanations and instructions in detail to the learners face-to-face before they answered the question to stop any misunderstanding. Then, semi-structured one on one interrogations for teachers and learners were conducted by the researchers haphazardly to 15 out of 98 learners to carry out personal interviews comprising two questions.

The interview questions’ objective was to gain detailed information on respondents’ feelings on some strategies and speaking classes used to improve oral fluency in English speaking. To gain reliable data, the experts transcribed the replies to the interviews as quickly as possible, a maximum of a day after the interrogations.

Discussion and Findings

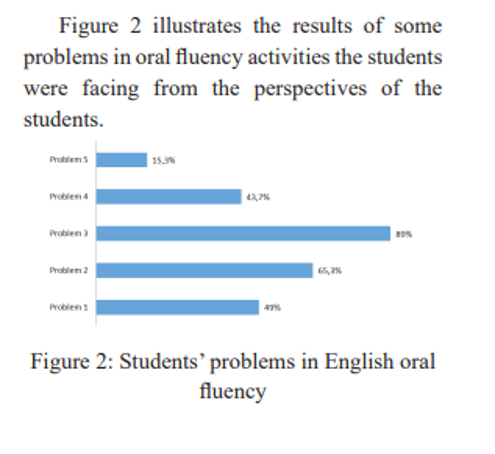

From the above figure, many learners (89%) felt hesitant to speak English in their classes. They were still determining whether they used English appropriately or vice versa; thus, they vacillated to speak. 65.3% implied they needed to be made aware if pauses in their speaking volumes were appropriate. Whereas 49% revealed that they could not think of anything to say or could not actualize the ideas in their mind in English-speaking lessons, a negligible number of 15.3% chose the matter emanating from their partner’s reaction.

As described earlier, the learners must finish their online lesson before each offline lesson to prepare input knowledge for their speaking actions in class. Although, the outcome gathered in Fig 2 made the experts desire to get the causes of the learner’s issuers. Thus, they asked the learners in their first interview questions.

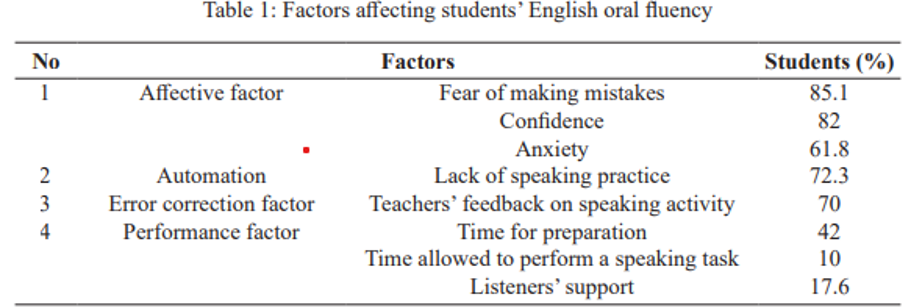

12 out of 15 shared that they had organized their online teachings before attending offline lessons with their teachers. It is visible that a significant number of students fell into the squad of affective factors, comprising 82 % for confidence, 85.1 % for fear of making mistakes, and 61.8 for anxiety.

In summary, the info from Fig 2 reveals that hesitation is the most concerning issue among the five listed issues to the learners. In the research on learners speaking issues, Tran and Nguyen (2015) confirm that learners are sometimes hindered as they aspire to say something in English. They become fearful of criticism and anxious about making blunders.

Rivers (1968) thinks students typically have little to discuss since their tutors pick a topic they need more info about or is inappropriate. Westrup and Baker (2003) also back up the outcome revealed in Fig 1, stating that it is pretty tough for learners to speak something confidently in English when they have various ideas about what to speak about, how to use grammar precisely, and which vocabulary to apply.

The outcome in the table above shows the factors resulting in the referred issues the learners encountered in their oral fluency above. The queries were raised in the learner’s interview to clear the air on affective factors. Many learners 13 of 15 stated that they were nervous in many of their English-speaking classes, which confirmed and supported the gathered outcomes in Table 1. Thus, now hidden reasons for the learned huge matter could be revealed.

The fear of making errors as one of the affective factors was the chief cause of making learners hesitate to produce language in conversations. Likewise, Nan and Yurong confirmed that the four affective factors ascertained the formation of oral English in their research about affective factors.

Tanveer (2007) also discovered that anxious learners may hinder their performance abilities and language learning. Also, Lin and Wu agreed that much anxiety resulted in a low willingness to converse. In the long while, it could have an undesirable impact on students’ achievement in a trailing language in the classroom.

Close to 75% of the learners saw automation factor-lack of communication practice- as an impactful factor to their oral fluency. These factors can be leisurely seen to be the leading cause of a second matter the students underwent. Schmidt (1992) stated that if the speed procedure were recalled automatically by English students daily, their fluency in speaking would achieve.

Nguyen (2015, p.52)also fortified that automation conceives fluency.

The probability of speaking English and the English surrounding were presented as the chief matter impacting the Chinese learner’s oral fluency in research conducted by Zhang et al. (2004). Thus, learners will only express themselves fluently if they practice speaking. They might have chunks of language or pause inappropriately as they converse.

Also, Bohlke (2014) stated that automation determined to a greater extent whether the learner could produce language fluently, and so did their exposure to the English environment. Learners could eventually use language unconsciously and naturally thanks to diving into English-speaking surrounding regularly.

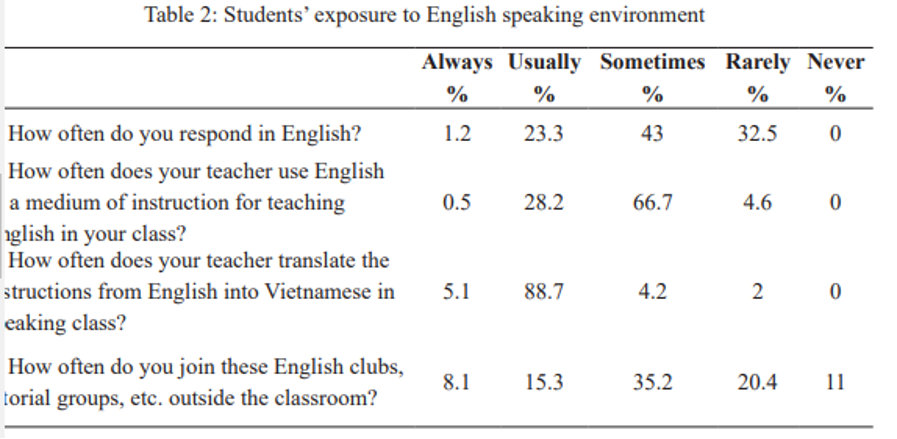

The table shows learners’ exposure to English-speaking surrounding (Richards, 2023). Initially, the info in Table 2 shows that the learner’s frequency response in English was not top with the percentage of 1.2%, 23.3%, 32.5%, and 43%for the choices of always, usually, rarely, and sometimes, respectively. Also, in line with giving directions in class, 28.2 selected the option of usually, 66.7 5 of the learners revealed that their tutors occasionally used English to give instructions in class, and a tiny number 4.6 and 0.5 % selected the rank of always and rarely respectively.

Thirdly, it can be viewed from Table 2 that a vast number of learners, 88.7%, agreed on the teacher’s high frequency of translating instruction from English to Chinese in speaking class. In the initial interrogation query for tutors, the experts inquired about the reason for the dominant numbers. They elaborated that most of the time, the learners inquired for an explanation as they could not wholly comprehend the instructions in English.

Also, to grasp whether the time span in English classes backs the learner’s oral fluency, the tutors were interrogated on fluency percentage activities in every lesson in the second question. To ensure that all the teachers were certain of the characteristics of accuracy-based and fluency-based activities, the experts explained them prior to the activities.

Every tutor agreed that 50-75%of the speaking program in the books were fluency-grounded activities. Also, these activities were always frequent in each lesson in their textbook. Also, they shared that every textbook used in their English course was structured for their own learner’s majors and internal circulation particularly (Nam et al., 2023).

Grounded on their learner need assessment, the board of qualified English designed the textbooks based on these needs. The information showed that the present distribution of speaking acts in the English lesson is advantageous for promoting learners or appropriate as it is much beyond the whole time for fluency-grounded activities proposed by Brumfit, as mentioned earlier in the research.

Finally, conferring participation in various English activities outside the classroom, it is significant that the number of learners frequent was low, with 15.3% usually and 8.1% always. Meanwhile, many (55.6%) rarely and sometimes joined some outside English class, as eleven percent have not attended any tutorial group or English clubs.

Table 2 data revealed that learners were presented in a limited English-speaking environment outside the classroom. This fact could elaborate the learner’s problems in willingness to express themself in English without inappropriate pauses or hesitation. Also, as can be deduced from Table 1, almost 75% of learners thought it was an error factor of correction leading to fluency problems (Vu, 2023).

This matter was closely linked to some influential factors presented beforehand. This implied that learners could feel shy if the tutors mentioned their speaking mistakes; they feared making mistakes or anxiety in speaking class. Tran and Nguyen (2015) also reported that tutor feedback influenced learners speaking performance in their study.

Conclusion and recommendation

For any English language learner, attaining fluency in speaking is critical. Accordingly, understanding the issues linked to fluency and the factors leading to these issues would contribute to aiding tutors in reaching their goals. In order to attain the objective of the research, the experts carried out interviews and questionnaires to reply to the research query.

The outcome of the study question displayed the learner’s five issues in oral fluency: nothing to say, inappropriate pauses, difficulty in replying, and limited expressions, ranging from the biggest to the smallest. More critically, grounded on the outcome of data analysis, the factors resulting from these issues were also seen. The group affective factor, particularly the fear of making mistakes, was vital among the participants.

Recommendations.

The tutors should aid their learners in overcoming shyness and inhibition by giving optimistic and gainful feedback. The tutors must carefully choose how and when to rectify the learner’s mistakes so that the learners are not fearful of making mistakes and student conversation is not harmed.

Tutors’ cooperative and friendly conduct can aid in making the learners feel comfortable and willing to speak in class. It is critical to nurture a surrounding where students and teachers habitually use English, mostly outside and inside the class. If the tutors give, sufficient guidance and explicit instruction can gradually get acclimatized to understanding instruction in English without translating into Vietnamese.

References

Cheung, A. (2023). Language teaching during a pandemic: A case study of Zoom use by a secondary ESL teacher in Hong Kong. RELC Journal, 54(1), 55–70.

Lei, F., & Lei, L. (2023). The impact of resilience, hope, second language proficiency, and number of foreign languages on Chinese college students’ creativity. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 48, 101275.

Liu, G., Ma, C., Bao, J., & Liu, Z. (2023). Toward a model of informal digital learning of English and intercultural competence: a large-scale structural equation modeling approach. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1-25.

Musa, M. (2023). Factors Influencing Student’s Attitudes Towards Learning English as a Foreign Language in Tertiary Institutions in Zanzibar, Tanzania. International Journal of Linguistics, 4(1), 14–26.

Nam, B. H., Yang, Y., & Draeger Jr, R. (2023). Intercultural communication between Chinese college students and foreign teachers through the English corner at an elite language university in Shanghai. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 93, 101776.

Richards, J. C. (2023). Teacher, learner, and student-teacher identity in TESOL. RELC Journal, 54(1), 252–266.

Vu, T. B. H. (2023). Teaching English speaking skills: An investigation into Vietnamese EFL teachers’ beliefs and practices. Issues in Educational Research, 33(1), 428–450.

write

write