1.0 Introduction

Death is a normal part of nursing practice and something which nurses will inevitably encounter regularly, although inexperienced nurses can frequently approach the situation with fear and anxiety (Strang et al., 2014). These feelings that student nurses can experience around taking care of patients at the end of their life is often due to a lack of education around end-of-life care, which unfortunately can alter the student nurses’ attitude to this type of care, impacting not only the patient but also the support provided to the patient’s family after they have passed away (Gillan et al., 2014). While advances in medicine and technology have helped increase life expectancy, there are still diseases and illnesses that can shorten an elderly patient’s lifespan (Heath foundation, 2019). Thus, palliative patients will require end-of-life care at some stage. When working around elderly patients and patients with long-term illnesses, student nurses will likely experience dying patients as part of their routine clinical practice (Brown, 2016; Poultney, Berridge, and Malkin, 2014). Student nurses and their practice supervisors also experience caring for dying patients more than any other health care professional in clinical settings (McCall, 2018). In most cases, nurses/student nurses can build an excellent practitioner-patient relationship with their patients near the end of their lives, which can often add to the emotional challenges faced by the nurse once the patient has passed away (Levett-Jones et al., 2015).

Therefore, learning how to develop coping strategies and caring for patients at the end of their life, as well as learning how to provide the proper support for the patient’s family once their loved one has passed away, is of great importance to the nursing profession and should be an integral part of the student nurses’ education. The decision to write about this subject was based on my personal experience as a student nurse when I was asked to provide care for one of the patients while undergoing a placement in a hospital. I realized that even though I had previously had a few lectures on the end of life care as part of my university’s curriculum, I still lacked adequate knowledge on this specific area of practice and felt I could not offer the proper support required. I also personally found it quite challenging to cope with the end of life care until I was faced with the situation, and once the time came, I realized I was unprepared. When the patient passed away, I had fear and anxiety over being around the patient’s body and received little support from the institution while attending the placement. Further, while working at the placement, I discussed the issues I was having with some of the other student nurses who shared the same feelings as I did, which made me realise that this is an of 3 25 common problems faced by student nurses and required more research on the subject. As theoretical knowledge is as crucial as practical knowledge for student nurses, it is essential to learn how to care for patients at the end of their lives, as well as how to put the theory into practice and also know how to cope once the patient passes away (Henoch et al., 2017; Osterlind et al., 2016).

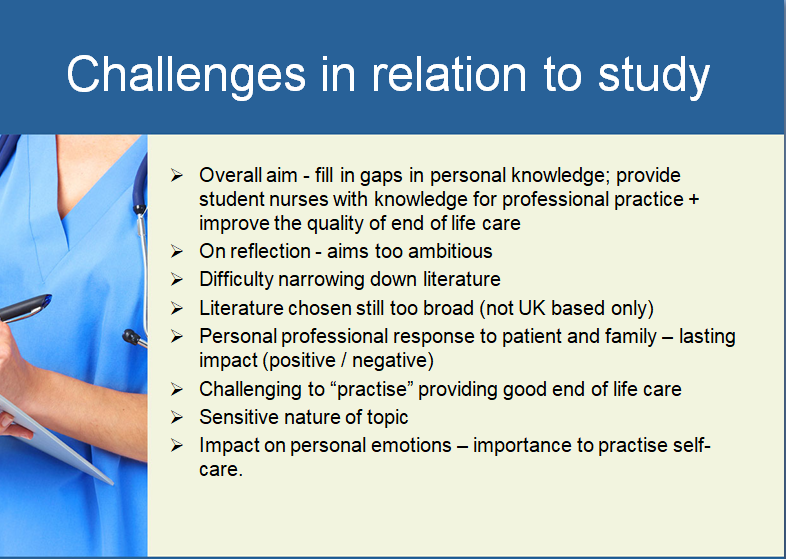

Much research suggests that student nurses are often underprepared in providing end-of-life care to dying patients, with a lack of skills to fully support the patient’s family and help them cope once their loved one passes away (McLeod-Sordjan, 2014). Thus, it is essential to provide student nurses with a more in-depth knowledge of end-of-life care before completing their education, including supporting families during these times (Ek et al., 2014). The following review of professional practice will explore the impact that education on end-of-life care has on the student nurses’ attitude and ability to care for patients during these times. The research will explore the impact that inadequate education on end-of-life care has on the student nurses perspective and mindset when caring for these patients, focusing on the support required to improve the student nurses’ ability and experiences in this area (Hold et al., 2015). This research aims to fill in the gaps in education and provide student nurses with the knowledge required to carry into their professional practice and improve the quality of end-of-life care. To better understand what education and skills are required, a search was performed to find education involving end-of-life care and its impact on the ability to care for dying patients. The results were analysed (Aveyard, 2014).

1.1 Search Terms

Several research databases were used to search for literature to fulfill this literature review, with the primary sources being the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the British Nursing Index, Medline, the National Institute of Care Excellence (NICE), the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) and Google Scholar. These databases and search platforms were chosen due to having a wide variety of literature specific to nursing and end-of-life patient care. CINAHL contained a lot of nursing literature in journal articles and books related to end of life care and mainly were all in English (Polit and Beck, 2017). The Boolean search engine provided more specific search terms when searching for literature on the medical journal database websites. The following words were searched separately, as well as in combinations with the Boolean operator ‘and’: ‘impact’ or ‘effect’ of ‘end of life care’ or ‘end of life patient,’ ‘education,’ ‘student nurses’ ability’ and ‘dying patient.’

Additionally, searches around nurses’ attitudes and feelings were performed on the same databases to assess the results. Other sites such as Google Scholar were used to search individual results of peer-reviewed journal articles. The ones that gave the most valuable and relevant results were found in the International Journal of Palliative Nursing, British Journal of Nursing, Journal of Interprofessional Care, and SAGE. These additional articles helped guide my literature search as experts in their fields all well-reviewed them, and as such, the findings were valid and reliable (Harvey and Land, 2016). It is also worth noting the difference between the inclusion and exclusion criteria while undertaking the literature search. (Demaerschalk et al. 2016) states that the exclusion criteria can produce ineligible results, whereas the inclusion criteria can make the subject more eligible for review. All of the literature added to the included search was in English, and all were either qualitative or quantitative studies. The majority of the excluded studies were unpublished, in a different language, contained sample sizes smaller than ten participants, or were more than five years old (Aveyard, 2014). However, some older pieces of work were included, such as the guidelines given by the World Health Organisation and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), as this information has yet to be updated and is still used within research and professional practice.

2.0 Literature review

A literature review helps identify the research gaps, identifies a need for additional research, and leads to new insights to better inform professional practice (Garrard, 2020). Using the search terms above, several eligible studies were retrieved. However, there were few studies from the United Kingdom alone; hence the country of the research was not limited to the United Kingdom yet also taken from wider Europe, Australia, and the United States to gain a broader scope of the views on the topic. However, it should be noted that it would have been beneficial only to include research from the United Kingdom. This would provide a sound evidence base for any future research within this country and be helpful for the National Health Service. The retrieved pieces of research for review were recorded in a matrix to show the selected articles, their limitations, the study results, sample sizes, the methodology used, the themes, and the outcome. The qualitative framework provided by (Price et al., 2017) was utilised as a way of analysing the selected research for their reliability and validity, which covered different aspects such as the purpose of the selected study, the relevant background to the literature, appropriate study design, adequate sampling methods, methods of data collection, implications and methods of analysis. Using this framework helped quickly identify the main areas for critique from each piece of selected research. Using the matrix to analyse the data helped identify the common themes emerging from the research. The most common themes were the importance of the practitioners’ beliefs around dying patients and their death and their previous personal and professional experience around caring for people at the end of their lives. Several sub-themes from the selected research for the student nurses were also highlighted as the experience of fear and anxiety and their relationships with their patients and family members, discussed in more detail below. Understanding how to minimise this is important as student nurses spend a lot of time caring for patients at the end of their life, and if the nurses are unprepared, then the level of care provided to the patients and their families will be a negative experience for all involved (Levett-Jones et al., 2015; Westwood, 2019). There have been many studies also showing the need to improve undergraduate nursing education surrounding the end of life patient care (Grubb and Arthur, 2016), although the themes analysed within the literature review will help to determine of 6 25 what areas can be improved upon and how this will impact the nurses’ ability to care for dying patients ( Li et al., 2019).

2.1 Theme One: Beliefs and Values About Death

One of the main factors that shape the student nurses’ ability to care for patients at the end of their life is the fear of seeing a corpse. However, other personal factors such as their religion, culture, scientific or spiritual beliefs/values also impact how student nurses can care for their dying patients, despite their fears (Oluwatomilayo et al., 2014). The student nurses have values around their beliefs about death that have created the most fear when caring for their end-of-life patients, thus impacting their abilities to carry out quality care (Jafari et al., 2015). However, it should be noted that many studies record that the students who have strong beliefs about there being life after death, despite other personal factors, recorded being less afraid and more comfortable when caring for their dying patients than the student nurses who had no such beliefs (Robinson and Epps, 2017). The qualitative study created by (Ek et al., 2014) discussed first-year nursing students’ experiences of caring for their dying patients and found that most of the students were fearful of the experience of death and being around a corpse for the first time. Some of the participants noted that their fear of seeing the corpse was due to the patient possibly looking different than they did alive. They were afraid of this new experience as it was unfamiliar. However, the limitations with this study are that all of the participants were first-year nursing students, all of whom were female, thus generalising the claim that student nurses are fearful of caring for dying patients cannot be made as participants from all levels of nursing education and of different genders have not been explored.

Further, there were only seventeen participants interviewed for the study, which (Price et al., 2017) state does fall between the recommended five to fifty participants to gain adequate results from their research. However, it is on the low end of this scale. ((Price et al., 2017) go on to add that they believe twenty-five to thirty participants is the optimal amount to gain a better insight into the subject being explored, and thus the study by (Ek et al., 2014) falls short of meeting this requirement. Despite this fact, it should be noted that this study was on first-year students who had yet to have the experience of being around dying or dead patients, thus emphasising the need for students to experience this and gain the excellent end of life care experience as early as possible in their education to eliminate these fears (Gillan et al., 2014).

A second study by (Guo & Jacelon, 2014). was produced to explore the student nurses’ first experiences of death within their clinical practice to identify the additional education, training, and support measures required in this area. The qualitative study consisted of five student nurses who highlighted four main themes from the data analysis: the emotional influence of death, the skills required to work in end-of-life care, the role of the mentor, and the relationships with the patients. The findings showed that all participants experienced considerable anxiety during their first experience of a patient dying, and they all noted that they felt underprepared to deal with it. They require support (Cruse Bereavement Care, 2020). Throughout the research, the students’ experiences record them witnessing a dramatic change in the psychical appearance of the patients once they had passed away, which caused the students to feel shocked and fear. Thus, supporting evidence from the previous study that students require training and support on dealing with these fears when working around death (McIntosh, 2014). Overall, the main strength of this study is that it shows the same results as the previous study reviewed above, hence supporting the need for improved education in this area. However, the main limitation is, once again, the small sample size consisting of only five participants, which was highlighted above by (Guo & Jacelon, 2014), to be too low to gain a thorough understanding of the topic.

Further, all participants were taken from the same institution, which is not a good representation of student nurses’ experience across the United Kingdom. The third study that researches student nurses’ beliefs and values around death was conducted by (Oluwatomilayo et al., 2014). This study was carried out in Australia, and the participants were third-year nursing students. The study aimed to explore their knowledge and education and how this related to their experiences of dying patients. It was found that their perceived level of education and their beliefs around what constitutes a good or bad death, and their ethics all factored into their ability to provide end-of-life care. The findings were similar to the previously reviewed studies in that there was still a lack of adequate education and experience, even at level three in their course. However, the questionnaires were sent out to third-year nursing students from the same university and only received a thirty-one percent response rate. This could create limitations with the study, (Cheung et al., 2017) explains; there could be a ‘response bias’ where it is likely that the only respondents to the questionnaire had negative experiences, and the ones who had positive experiences with end of life care did not feel they had anything to contribute or did not feel the need to discuss their experiences. This is similar to consumers and how it is more likely that when a consumer has a negative experience, they will be far more inclined to share their experience and be open about it, compared to the consumers who have a positive experience and do not feel the need to talk about it (Thomas, 2018). Further, the participants were all gathered from the same university, thus cannot represent the country and culture. However, it does provide some information on how there is still a lack of education on end-of-life care present in the later levels of a nursing degree. This was highlighted in the study as they comment that there is a need for regular education intervals on the end of life care throughout the nursing degree. The student nurses can build a positive attitude and skill set within their professional practice (Oluwatomilayo et al., 2014).

Cancer is one of the major diseases that today’s health and treatment systems face. Every year, the number of cancer patients and their mortality rate increases globally. They have physical, emotional, psychological, and social issues while sick. Palliative care has emerged in recent years to help these people, provide appropriate care, and manage many issues. Palliative care requires a framework with precise actions to achieve its goals. The relationship between service providers (care team) and patients is one of the essential elements of effective palliative care (patients). Ignoring this guideline may complicate care delivery. Relationships in palliative care enhance decision-making and interdisciplinary treatment. In contrast, a good relationship between the care provider team and the patient leads to patient satisfaction and adaptability to cancer. In numerous studies, connection development has been identified as a critical part of palliative care quality. The care team’s communication skills and techniques establish the relationship’s nature and overcome the caregiver system’s problems (Vanaki et al., 2020).

2.2 Theme Two: Previous Experience of Caring for Dying People

Many studies have found a connection between student nurses who have cared for dying people in their personal lives and how this translates to their attitude and ability to care for dying patients within their professional practice (Gama & Vieira, 2014). The first study to be reviewed in this theme is by Hagelin et al. (2016), which studied the attitudes and abilities of first-year student nurses when caring for dying patients. The study found that student nurses who were advanced in their learning and had previous healthcare experience had more positive attitudes around caring for dying patients. This was due to their level of education combined with their experience, thus showing that both factors can have positive outcomes on patient care. However, this study was completed in Sweden; hence, cultural attitudes and beliefs around death can differ from those in the United Kingdom. Further, the participants were primarily female, which could also alter the results as (Dodd & Mills, 2017) ‘s study shows that women were generally found to experience more anxiety around death than men. The second study was created by Robinson and Epps (2017) and consisted of seventy-four student nurses. The study explores the participants’ knowledge and ability to care for patients at the end of their life. The research found that senior students reported having negative feelings about caring for dying patients as early as the start of their course and highlighted the students’ lack of exposure throughout their course when meeting dying patients. The main strength of the research was that there were adequate participants in the study to make this statement and draw this conclusion. Further, all participants were senior students, thus providing information on their knowledge and experience from beginners to graduate nurses.

However, the limitations could be that all participants were from the same course/institution, and therefore the educational standards may be different from other courses in other institutions. The third study was conducted by Poultney et al. (2013) in the United Kingdom to support student nurses in their experience of caring for end-of-life patients and handling death from the moment they joined their course. The study highlighted that the student nurses who had no previous experience in caring for a dying person, either personally or professionally, were highly likely to have a negative attitude towards carrying out end-of-life care and seeing a corpse. The researchers wanted to expose the student nurses to opportunities to care for end-of-life patients from the beginning of the course and interviewed the students about how they would feel about this beforehand (Berndtsson et al., 2019). In this way, the approach to nursing education was found to create a positive attitude towards the end of life care. It enhanced the student nurses’ ability to cope with death, compared to the previous study with little knowledge and exposure, leaving the students with negative attitudes towards this type of care (Zahran et al., 2021). This piece of research was beneficial to the university. It was designed to improve their course; however, no transparent methodology as stated in the research. Their method was to interview nurses and describe their feelings on the end of life patient care during a classroom session, which does not meet the criteria for an acceptable phenomenological research study (Creswell and Cresswell, 2018). Furthermore, the sample size of this study consisted of fifteen participants from the same university and had no straightforward sampling process; therefore, the results cannot be relied upon for application in general use.

3.0 Discussion

The following chapter will take the points raised in the literature review and discuss them using supporting references. The beliefs and values of student nurses and their previous experience of caring for dying people were researched. The impact these factors can have on the nurse’s attitude translates to the level of care provided. The studies reviewed, and many others on this topic suggest that how prepared the student nurses are for caring for end-of-life patients directly correlates to their ability and attitude to carry out quality care (Davenport, 2020). This can be seen in the comparison between student nurses at the start of their course compared to student nurses at the end of their course; the former, who had received little to no education or experience, mainly reported negative attitudes and a lack of ability around the end of life care, with the latter who, once had received adequate knowledge and experience, most reported positive attitudes and abilities towards the end of life care (Lippe and Becker, 2017).

However, for the institutions that do not provide adequate education and experience on the end of life care throughout their nursing programs, this can result in qualified nurses who still lack the ability when care for end-of-life patients. They may experience fear and anxiety and fail to create a solid patient-practitioner relationship (Hendricks-Ferguson et al., 2015). Some underprepared nurses may even avoid the patient, which could ultimately create a negative experience for both the nurse and the patient, potentially resulting in the nurse leaving the profession and causing a lack of end-of-life care specialists (Henoch et al., 2017). Providing quality care that includes emotionally supporting the dying patient and their family is an essential clinical skill in the nursing profession (Brown, 2016). The nurse’s first experience with end-of-life care can profoundly affect their ability to carry out this type of care to a high standard (Menekli and Fadiloglu, 2014). However, adequate research suggests that student nurses enter the profession lacking this clinical skill, which causes them to feel fearful and avoid the dying patient, thus failing to provide a high level of care (Anderson et al., 2015; Ranse, Ranse and Pelkowitz, 2017).

Furthermore, (Robinson, & Epps, 2017). highlight that when student nurses have had little education on end of life care and then go on to experience dying patients early on in their studies, they can be significantly affected by these first experiences, which can lead to acute helplessness and increased anxiety when faced with similar situations in the future. Even though the literature review found that some student nurses had received adequate education on end-of-life care by the final year of their course, other studies revealed that this was not always the case, depending on the institution and country of study. Therefore, comprehensive training on the end of life care to develop essential clinical skills in this area needs to be embedded into the nursing curriculum nationwide to fully prepare the student nurses to feel confident and capable of providing a high level of care to their end of life patients (Sprung et al., 2014). The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) (2018) highlights the importance of end-of-life care education. It states that they are committed to ensuring that the forty-four recommendations and five priorities of caring for end-of-life patients are reflected in the nurses’ values and behaviors towards their patients, which should be part of the pre-registration education standards. They state that the five priorities for end of life care are:

- Recognising that the patient may shortly die and communicating clear decisions made and the actions to be taken according to the patient’s needs and wishes, which should be reviewed and revised regularly.

- Sensitive communication should occur between the staff, patient, and anyone else crucial to the patient.

- Involving the patient’s family or those who are essential and involving them in treatment decisions and care within the extent of the patient’s wishes.

- Supporting the needs of family and significant others and ensuring their needs are respected and met as much as possible.

- Preparing the patient’s care plan, which includes nutrition, symptom management, psycho-social and spiritual support, should be coordinated and provided with compassion.

Regardless of the NMC stating that these standards should be part of the nursing education, they do not specify at what stage in the nurses’ education that end of life care should be incorporated to prepare the student nurse towards entry onto the nursing register (Cavaye and Watts, 2014). Additionally, the NICE (2017) guidelines on end of life care also require that education providers and pre-registered nurses are competent in delivering this type of care. However, they also do not specify the content or stages at which student nurses should be receiving this education, thus creating a lack of specified and uniform content to be available in nursing education to produce the standards set out in these guidelines (Adesina, DeBellis, and Zannettino, 2014). Further, Rotter and Braband (2020) add that in addition to the nursing curriculum and education on end of life care, opportunities in hospital placements should be available to develop clinical skills in this area and further strengthen practice in preparation for becoming a qualified nurse. Aside from this issue with education standards for student nurses in the United Kingdom, many nursing students from overseas aspire to work in hospitals in the United Kingdom after graduating (Allan & Westwood, 2016). Therefore, the NMC must work together with the World Health Organisation to highlight creating global standards towards end of life care in a person-centered, equal opportunities approach that considers different perspectives of people from all backgrounds (WHO, 2014). Many patients in Western society die in hospitals. However, the aspect of patient death is not regarded as part of the core business of a hospital as the main focus is on saving lives as opposed to providing quality end-of-life care (Andersson et al., 2016). Thus, end-of-life care is increasingly considered a specialty within nursing, which very few nurses enter into within their professions (Brown, 2016). This means that many terminally ill patients are being treated in non-specialist areas within the hospital by unskilled nurses in this type of care; hence student nurses frequently encounter dying patients while on hospital placements (Chow et al., 2014). While this may help with experience for the student nurses, the literature reviewed above also highlights a consistent lack of education to support these experiences, as many student nurses reported negative emotions and felt unprepared for all involved with this type of care (RCNI, 2020). Therefore, it should be critical for hospitals to integrate end-of-life care training sessions to improve the student nurses’ knowledge in this area if they face caring for dying patients for the first time while on placement (Poultney et al., 2016). However, it should be noted that incorporating such training sessions will be costly to the hospital, although it could potentially be delivered online to minimise costs.

Moreover, research conducted by (Osterlind et al., 2017) found that one of the factors that lead to student nurses’ fear and ability to care for dying patients, regardless of whether they have had adequate education on this type of care, is their fear of seeing the patient once they are dead. The study highlights how even if an institution provides information on how to best care for a patient at the end of their life, there is little discussed in terms of the appearance of a corpse. Lack of education around seeing a corpse and what to expect can result in a negative first experience for the student nurse, leading to avoidance and lack of quality care. Further, there was also little education on managing one’s own emotions after the patient’s death, which is another essential aspect of ensuring it is not a negative experience for the nurse (Poultney, 2013). If the student nurse has a positive relationship with their mentor, this can lead to positive outcomes over their experience of caring for a dying patient (McIntosh et al., 2014). Throughout the student nurses’ clinical practice, most will experience last offices to ensure they handle this positively. The mentor should look to support the student nurse, both before and after the patient has died, intending to develop their coping strategies and resilience (Goodman, 2015). However, if the mentor’s support is not present in these situations, it has been shown that this can contribute towards the student nurses’ negative feelings and lack of ability to care for dying patients, especially when the individual has little existing experience of this situation (Ek et al., 2014). According to the NMC (2018), it is a requirement that healthcare institutions train student nurses to be compassionate and caring towards their patients, including dying patients. Thus, a supportive environment and mentor are required to achieve this goal. Training with such support in this area can increase the student nurses’ resilience when coping with dying patients and death (McCall, 2018) agrees and adds that more emphasis should be given to support mentorship and peer support as a part of nurse training programs to build the required resilience around death. Establishing the individual nurse’s feelings towards caring for end-of-life patients will also help guide the mentor and help the student reduce their anxiety, build resilience, and improve their abilities (Gillan et al., 2014).

However, the typical bereavement care in nursing practice usually only focuses on the needs of the patient’s loved ones, with little consideration given to the nurse’s needs (RCNI, 2020). There is a lack of literature that considers bereavement care for nurses and how they can use their experiences and emotions to strengthen their resilience and improve their practice. Thus, nurses should consider including them in bereavement care if they wish to do so, which usually only consists of a counselor assessing the patient’s loved ones and helping them handle their loss (Beckett and Taylor, 2016). As grief affects everyone differently and the effects are not just limited to the patient’s family yet also extend to those who knew the individual, nurses must be considered for bereavement counseling within their institution once they have been through the experience of losing a patient. This measure will also help to ensure positive outcomes for future patient care. Other factors to consider individually are the nurse’s religious, cultural, social, and philosophical beliefs about death (Robinson and Epps, 2017). (Henrie & Patrick, 2014). Through their study, student nurses who hold religious beliefs about death and an after-life approach end of life care with much less anxiety than the non-religious student nurses. However, adequate education and mentorship can be put in place individually to improve anxiety and ability in non-religious student nurses through the considerations provided above (Gillan et al., 2014). Once the student nurse has this support in place and has gained a lot of experiences within their practice surrounding the end of life care, there is evidence to suggest that they will approach death more positively, and their care ability will also improve over time (Hagelin et al., 2016). One factor that the mentor can encourage the student nurses is to foster a close relationship with the patient on a personal level, which has been shown to create a positive attitude and increase care abilities in the nurse’s future practice (Ek et al., 2014). This is also beneficial for the patient to feel reassured and cared for in their final days of life (Sinclair et al., 2017). However, without proper support and coping strategies, developing a solid relationship with the patient could be detrimental to the nurse and their future ability to cope at the end of life care (Edo-Gual, Tomás-Sábado, and Bardallo-Porras, 2014). Thus, adequate education, mentorship, and the chance for the student nurse to explore their feelings through bereavement care are all essential to building a positive experience for both the nurse, patient, and the patient’s loved ones, and is required to achieve and sustain a high level of compassionate care (Beckett, 2016; Efstathiou & Walker, 2014).

4.0 Conclusion

As a medicine, technology, and the awareness of a healthy lifestyle have all advanced dramatically over the last few decades, the average life expectancy has risen in the United Kingdom. Due to this, end-of-life care is becoming an essential skill within clinical care (Poultney et al., 2014). Despite this need, many hospitals’ main focus remains on saving patients’ lives instead of providing end-of-life care (Brown, 2016). This has resulted in an unbalanced allocation of resources within other departments and is reflected in the undergraduate nursing curriculum, where there is minimal focus on the end of life care. After reviewing the literature, it is clear that most student nurses will struggle to provide a high level of end-of-life care without proper education and support. After exploring the literature further in the discussion, it was found that there is a consensus that student nurses feel underprepared to care for dying patients due to the lack of education and experiences they are exposed to during their studies. However, it was also discussed that the initial fear and negative feelings towards the end of life care could be turned around with adequate education and support, combined with multiple chances to experience this type of care in practice. The research also found that personal experience can shape how the student nurses feel they can care for dying patients (Oluwatomilayo et al., 2014).

Some may have had a negative first experience with death, making the student nurse avoid dying patients in future situations. In contrast, others find that multiple experiences, combined with support, have helped to strengthen their practice. Although the student nurses with no experience in this area often enter the profession with many negative emotions, such as fear and anxiety. Further, it was discussed that religion and beliefs around death could also contribute to the nurses’ experience and care. As such, culture can play a part; for example, international nurses who come to work in the United Kingdom may be from very spiritual/religious backgrounds, and thus may be better able to cope with end of life care in comparison to cultures that are less religious such as in the West. Regardless of religion, many students enter the profession with some pre-conceived beliefs around death, such as the presence of spirits or the apprehension of being around a corpse, which can negatively affect patient care. However, it was found that despite the student nurses’ beliefs, culture, and background, with adequate education, experience, and support, all will gain knowledge on end-of-life care and, with multiple experiences, can enter into reflective practices to develop their skills. The NMC and NICE guidelines have specific requirements for end of life care and the skills required to provide this. Yet, hospitals within the United Kingdom operate with 16 25 more focus on saving lives, becoming a more prominent focus in training. As dying patients are admitted to general wards, nurses spend more time practicing end-of-life care than other health care professionals (McCall, 2018). hence there is a real need for the NMC to implement a transparent and evidence-based program for pre-register nurses to ensure institutions provide a high level of education surrounding the end of life care throughout the whole curriculum. Once this is in place, the student nurses will be prepared for their professional practice and be better able to support their patients and their loved ones, leading to higher levels of care and a more dignified end to the dying patient’s life.

References

Adesina, O., DeBellis, A., Zannettino, L. (2014) ‘Third-year Australian nursing students’ attitudes, experiences, knowledge, and education concerning end-of-life care, International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 20, pp.395-401.

Allan, H. T., & Westwood, S. (2016). English language skills requirements for internationally educated nurses working in the care industry: Barriers to UK registration or institutionalized discrimination? International journal of nursing studies, 54, 1-4. Retrieved from: http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/14707/1/ELSBarrierstoRegIJNSeditorialha1512a.pdf

Andersson, E., Salickiene, Z., & Rosengren, K. (2016). To be involved—A qualitative study of nurses’ experiences caring for dying patients. Nurse education today, 38, 144-149. Retrieved from: https://www.academia.edu/download/57229669/Andersson.pdf

Anderson, N. E., Kent, B., Owens, R. (2015) ‘Experiencing patient death in clinical practice: Nurses’ recollections of their earliest memorable patient death,’ International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52, pp.695-704.

Aveyard, H. (2014) Doing a Literature Review in Health and Social Care. A Practical Guide. 3rd Edition, Open University Press: London.

Beckett, C., Taylor, H. (2016) Human Growth and Development, 3rd edn. London: Sage.

Brown, M. (2016) Palliative Care in Nursing and Healthcare. London: Sage.

Berndtsson, I. E., Karlsson, M. G., & Rejnö, Å. C. (2019). Nursing students’ attitudes toward care of dying patients: A pre-and post-palliative course study. Heliyon, 5(10), e02578. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844019362383

Cavaye, J., Watts, J. H. (2014) ‘An integrated literature review of death education in pre-registration nursing curricula: Key themes’, International Journal of Palliative Care, 14, doi.org/10.1155/2014/564619.

Chow, S. K. Y., Wong, L. T. W., Chan, Y. K., Chung, T. Y. (2014) ‘The impact and importance of clinical learning experience in supporting nursing students in end-of-life care: cluster analysis,’ Nurse Educ Pract, 4(5) pp.532–7.

Creswell, J. W., Creswell, J, D. (2018) Research Design. Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 5th Edn. California: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Cheung, K. L., Peter, M., Smit, C., de Vries, H., & Pieterse, M. E. (2017). The impact of non-response bias due to sampling in public health studies: a comparison of voluntary versus mandatory recruitment in a Dutch national survey on adolescent health. BMC public health, 17(1), 1-10. Retrieved from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-017-4189-8

Cruse Bereavement Care (2020) Supporting other people. [online] Available at: https://www.cruse.org.uk/understanding-grief/supporting-other-people/ [Accessed 18 November 2021].

Davenport, F. (2020) ‘Preparing students for end-of-life care and death How can nursing students best be prepared for end-of-life and after-death care,’ Nursing New Zealand, 26(7), pp.124-136.

Demaerschalk, B., Kleindorfer, D., Adeoye, O., Demchuk, A., Fugate, A., and Grotta, J. (2016) Scientific Rationale for the Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Intravenous Alteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins American Heart Association. pp.7-24.

Dodd, D. K., Mills, L. L. (2017) ‘Faddis: A Measure of the Fear of Accidental Death and Injury,’ The Psychological Record, 35, pp.269-275.

Edo-Gual, M., Tomás-Sábado, J., Bardallo-Porras, D. (2014) The impact of death and dying on nursing students: an explanatory model’, J Clin Nurs, 23(23–24), pp.3501–12.

Efstathiou, N., Walker, W. (2014) ‘Intensive care nurses’ experiences of providing end-of-life care after treatment withdrawal: A qualitative study, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21-22, pp.3188-3196.

Ek, K., Westin, L., Prahl, C., Osterlind, J., Strang, S., Bergh, I., Henoch, I., Hammarlund, K. (2014) ‘Death and caring for dying patients: exploring first-year nursing students’ descriptive experiences,’ Int J Palliat Nurs, 20(4), pp.194–200.

Ferri, P., Di Lorenzo, R., Vagnini, M., Morotti, E., Stifani, S., Herrera, M. F. J., … & Palese, A. (2021). Nursing student attitudes toward dying patient care: A European multicenter cross-sectional study. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 92(Suppl 2). Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmc8138802/

Garrard, J. (2020). Health sciences literature review made easy. Retrieved from: http://samples.jblearning.com/9781284115192/9781284133950_FMxx_i_xvi.pdf

Gillan, P. C., van der Riet, P. J., & Jeong, S. (2014). End of life care education, past and present: A review of the literature. Nurse Education Today, 34(3), 331-342. Retrieved from: https://www.academia.edu/download/41217064/End_of_life_care_education_past_and_pres20160113-25699-1fmo7fu.pdf20160115-19908-1x9h1z4.pdf

Gama, G., Barbosa, F., & Vieira, M. (2014). Personal determinants of nurses’ burnout at the end of life care. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18(5), 527-533. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Filipe-Barbosa-3/publication/262806716_Personal_determinants_of_nurses%27_burnout_in_end_of_life_care/links/559593c208ae99aa62c72f5e/Personal-determinants-of-nurses-burnout-in-end-of-life-care.pdf

Goodman, B. (2015) Psychology and Sociology in Nursing, 2nd edn. London: Sage.

Guo, Q., & Jacelon, C. S. (2014). An integrative review of dignity in end-of-life care. Palliative medicine, 28(7), 931-940. Retrieved from: http://wwwuser.gwdg.de/~pctgoe/DATA/Gunnar/PALLIATIV/Langeoog_2018/Kommunikation/dignity%20in%20eol%202014.pdf

Grubb, C., Arthur, A. (2016) ‘Student nurses’ experience of and attitudes towards care of the dying: a cross-sectional study, Palliative Medicine, 30(1), pp.83-88.

Hagelin, C. L., Melin-Johansson, C., Henoch, I., Bergh, I., Ek, K., Hammarlund, K., Prahl, C., Strong, S., Westin, L., Osterlind, J., Browall, M. (2016) ‘Factors influencing attitude toward the care of dying patients in first-year nursing students, International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 22(1), pp.28-36.

Harvey, M., Land, L. (2016) Research Methods for Nurses and Midwives: Theory and Practice. London: SAGE Publications. Heath foundation (2019) Harnessing data and technology for public health: five challenges. [Online]. Available at: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/ harnessing-data-and-technology-for-public-health-five-challenges [Accessed 17 November 2021].

Henrie, J., & Patrick, J. H. (2014). Religiousness, religious doubt, and death anxiety. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 78(3), 203-227. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Julie-Hicks-Patrick/publication/266325543_Religiousness_Religious_Doubt_and_Death_Anxiety/links/5680038908ae1e63f1e942b2/Religiousness-Religious-Doubt-and-Death-Anxiety.pdf

Hendricks-Ferguson, V. L., Sawin, K. J., Montgomery, K., Dupree, C., Phillips-Salimi, C. R., Carr, B., & Haase, J. E. (2015). Novice nurses’ experiences with palliative and end-of-life communication. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 32(4), 240-252. Retrieved from: https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/bitstream/handle/1805/6443/Hendricks-Ferguson_2015_novice.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Henoch, L., Melin-Johansson, C., Bergh, I., Strang, S., Ek, K., Hammarlund, K., Hagelin, C. L., wastin, L., Osterlind, J., Browall, M. (2017) ‘Undergraduate nursing students’ attitudes and preparedness toward caring for dying persons – a longitudinal study,’ Nurse Education in Practice, 26, pp.12-20.

Holloway, R. G., Arnold, R. M., Creutzfeldt, C. J., Lewis, E. F., Lutz, B. J., McCann, R. M., … & Zorowitz, R. D. (2014). Palliative and end-of-life care in stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke, 45(6), 1887-1916. Retrieved from: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?output=instlink&q=info:Bj7piQVegXsJ:scholar.google.com/&hl=en&as_sdt=0,5&as_ylo=2014&as_yhi=2020&scillfp=7725473989558381762&oi=lle

Hold, J. L., Blake, B. J., & Ward, E. N. (2015). Perceptions and experiences of nursing students enrolled in a palliative and end-of-life nursing elective: A qualitative study. Nurse Education Today, 35(6), 777-781.

Jafari, M., Rafiei, H., Noormohammadi, M. (2015) ‘Caring for dying patients: attitude of nursing students and effects of education, Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 21(2), pp.192-197.

Levett-Jones, T., Pitt, V., Courtney-Pratt, H., Harbrow, G., & Rossiter, R. (2015). What are the primary concerns of nursing students as they prepare for and contemplate their first clinical placement experience?. Nurse education in practice, 15(4), 304-309. Retrieved from: http://journal.stembi.ac.id/medias/journal/1_7-PDF_Pages_304-309.pdf

Lippe, M. P., Becker, H. (2015) ‘Improving attitudes and perceived competence in caring for dying patients: An end-of-life simulation,’ Nursing Education Perspectives, 36, pp.372-378.

Li, J., Smothers, A., Fang, W., & Borland, M. (2019). Undergraduate nursing students’ perception of end-of-life care education placement in the nursing curriculum. Journal of hospice and palliative nursing: JHPN: the official journal of the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, 21(5), E12. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6731147/

McCall, K. (2018) Effects of transformational learning on student nurses’ perceptions and attitudes of caring for dying patients. Doctoral dissertation, Walden University. [Online]. Available at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/5102/ [Accessed 17 November 2021].

McIntosh, A. (2014) ‘Mentors’ perceptions and experiences of supporting student nurses in practice: Student support: The role of mentors’, International Journal of Nursing Practice, 20(4), pp.360-365.

McLeod-Sordjan, R. (2014) ‘Death preparedness: a concept analysis, Journal of Advanced Nursing,70(5),pp.1008-1019.Retrievedfrom: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.948.5907&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Menekli, T., Fadıloglu, C. (2014) ‘Examination of the perception of death of nurses and the factors affecting them,’ Journal of Anatolia Nursing and Health Sciences, 17(4), pp.222– 229.

NICE (2017) Care of Dying Adults in the Last Days of Life. [Online]. Available at: https:// www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs144 [Accessed 20 November 2021].

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2018) The Code: Professional Standards of Practice and Behaviour for Nurses, Midwives, and Nursing Associates. [Online]. Available at: https:// www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/nmc-publications/nmc-code.pdf [Accessed 20 November 2021].

Oluwatomilayo, A., DeBellis, A., Zannettino, L. (2014) ‘Third-year Australian nursing students’ attitudes, experiences, knowledge, and education concerning end-of-life care,’ International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 20(8), pp.395-401.

Osterlind, J., Prahl, C., Westin, L., Strang, S., Bergh, I., Henoch, I., Hammarlund, K., Ek, K. (2016) ‘Nursing students’ perceptions of caring for dying people, after one year in nursing school,’ Nurse Education Today, 41, pp.12-16.

Polit, D., Beck, C. (2017) Essentials of Nursing Research. Philadelphia: Absolute Service Inc. 1-25.

Poultney, S., Berridge, P., Malkin, B. (2014) ‘Supporting pre-registration nursing students in their exploration of death and dying,’ Nurse Education in Practice, 14(4), pp.345-349.

Price, Deborah M., Linda Strodtman, Marcos Montagnini, Heather M. Smith, Jillian Miller, Jennifer Zybert, Justin Oldfield, Tyler Policht, and Bidisha Ghosh. “Palliative and end-of-life care education needs of nurses across inpatient care settings.” The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing 48, no. 7 (2017): 329-336. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Linda-Strodtman/publication/312527372_Assessment_of_Self-Perceived_End-Of-Life_Care_Competencies_of_Healthcare_Providers_at_a_Large_Academic_Medical_Center_S755/links/5ae7161ca6fdcc5ca03bddbe/Assessment-of-Self-Perceived-End-Of-Life-Care-Competencies-of-Healthcare-Providers-at-a-Large-Academic-Medical-Center-S755.pdf

Ranse, K., Ranse, J., Pelkowitz, M. (2017) ‘Third-year nursing students’ lived experience of caring for the dying: A hermeneutic phenomenological approach, Contemporary Nurse, 54(2), pp.160–170.

Robinson, E., & Epps, F. (2017). Impact of a palliative care elective course on nursing students’ knowledge and attitudes toward end-of-life care. Nurse Educator, 42(3), 155-158. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Fayron-Epps/publication/309268444_Impact_of_a_Palliative_Care_Elective_Course_on_Nursing_Students%27_Knowledge_and_Attitudes_Toward_End-of-Life_Care/links/610030ff169a1a0103bf4d42/Impact-of-a-Palliative-Care-Elective-Course-on-Nursing-Students-Knowledge-and-Attitudes-Toward-End-of-Life-Care.pdf

RCNI (2020) Role and support needs of nurses in delivering palliative and end of life care’, Nursing Standard, 25 October. [Online]. Available at: https://journals.rcni.com/nursing-standard/evidence-and-practice/role-and-support-needs-of-nurses-in-delivering-palliative-andend-of-life-care-ns.2021.e11789/abs [Accessed 20 November 2021].

Robinson, E., Epps, F. (2017) ‘Impact of a Palliative Care Elective Course on Nursing Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes Toward End-of-Life Care,’ Nurse Educator, 42(3), pp.155-158.

Rotter, B., Braband, B. (2020) ‘Confidence and Competence in Palliative Care,’ Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 22(3), pp.196-203.

Sinclair, S., Beamer, K., Hack, T. F., McClement, S., Bouchal, S. R., Chochinov, H. M., Hagen, N. A. (2017) ‘Sympathy, empathy, and compassion: a grounded theory study of palliative care patients’ understandings, experiences, and preferences,’ Palliative Medicine, 31(5), pp.437-447.

Sprung, C. L., Truog, R. D., Curtis, J. R., Joynt, G. M., Baras, M., Michalsen, A., … & Avidan, A. (2014). We are seeking worldwide professional consensus on the principles of end-of-life care for the critically ill. The Consensus for Worldwide End-of-Life Practice for Patients in Intensive Care Units (WELPICUS) study. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 190(8), 855-866. Retrieved from: https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1164/rccm.201403-0593CC

Teslim, O. A., Oluwatomilayo, R. A., Adebisi, S. O., & Folorunsho, I. A. Medication prescription policy for Nigerian physiotherapists: perception of orthopedic surgeons and neurologists on educational training and clinical management plans. Retrieved from: https://www.internationalscholarsjournals.com/articles/medication-prescription-policy-for-nigerian-physiotherapists-perception-of-orthopaedic-surgeons-and-neurologists-on-educ.pdf

Strang, S., Bergh, I., Ek, K., Hammaslund, K., Prahl, C., Westin, L., Osterlind, J., Henoch, I. (2014) ‘Swedish nursing students’ reasoning about emotionally demanding issues in caring for dying patients. International Journal of Palliative Nursing; 20: 4, pp.194-200.

Thomas, A. (2018) The Secret Ration That Proves Why Customer Reviews Are Important. [Online]. Available at: https://www.inc.com/andrew-thomas/the-hidden-ratio-that-couldmake-or-break-your-company.html [Accessed 19 November 2021].

Vanaki, Z., Aghaei, M. H., & Mohammadi, E. (2020). Emotional bond: The nature of the relationship in palliative care for cancer patients. Indian journal of palliative care, 26(1), 86. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7017707/

Westwood, S. (2019) ‘Preparing students to care for patients at the end of life’, Nursing Times, 23 September [online]. Available at: https://www.nursingtimes.net/roles/nurse-educators/ preparing-students-care-patients-end-life-23-09-2019/ [Accessed 19 November 2021].

World Health Organization (2014) Global Atlas of Palliative Care, 2nd edn. [Online]. Available at:https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/integrated-health-services-(ihs)/ csy/palliative-care/whpca_global_atlas_p5_digital_final.pdf?sfvrsn=1b54423a_3 [Accessed 20 November 2021]. 24

Zahran, Z., Hamdan, K., Hamdan‐Mansour, A., Allari, R., Alzayyat, A. and Shaheen, A., 2021. Nursing students’ attitudes towards death and caring for dying patients. Nursing Open, 9(1), pp.614-623.

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix C

write

write