Introduction

The Obligation to Safeguard (R2P) arose as a critical worldwide standard in the mid-2000s, Reflecting the global local area’s obligation to prevent mass atrocities and safeguard vulnerable persons (Claes, 2012). It declares that states should defend their residents from massacre, atrocities, ethnic purifying, and wrongdoings against humankind. Be that as it may, when a state neglects to satisfy this obligation or becomes the culprit of such atrocities, the global-local area, addressed by the Assembled Countries (UN), must mediate. The R2P rule envelops three support points: the obligation of the state to safeguard its populace, the obligation of the global-local area to help states in satisfying this obligation, and the obligation of the worldwide local area to mediate when states neglect to safeguard their populaces (Welsh and Banda, 2010).

The Libyan struggle, unfurled in 2011, gives a vital contextual investigation to examine the viability of the UN’s use of the Obligation to Safeguard standard. The contention started as a famous uprising against the despotic system of Muammar Gaddafi and quickly swelled into an undeniable nationwide conflict (Baughin, 1989). The swift international response to the Libyan case and the explicit use of the Responsibility to Protect principle to justify intervention make it stand out. The adoption of Resolution 1973 by the UN Security Council granted authorization for military action to safeguard Libyan civilians, which marked a turning point in the implementation of R2P.

The conflict in Libya demonstrated the difficulties in achieving the desired outcomes of civilian protection, stability, and long-term peacebuilding, as well as the complexity of R2P implementation. The UN’s intervention in Libya’s successes and failures can shed light on the Responsibility to Protect principle’s efficacy, reveal lessons learned, and guide subsequent interventions in situations where mass atrocities are imminent or ongoing.

The protection of civilians, the transition to stability, humanitarian concerns, and regional ramifications of the UN’s application of the Responsibility to Protect principle in Libya are the primary areas of focus in this report. By dissecting these key perspectives, the report plans to give an extensive comprehension of the results of the UN mediation in Libya and its viability in satisfying the goals of R2P. Moreover, the report will analyze the difficulties experienced during the mediation and draw examples that can improve the worldwide local area’s reaction to comparable contentions later on.

It is essential to acknowledge that evaluating the efficacy of R2P in Libya is a complicated endeavor that necessitates a nuanced comprehension of the complex nature of the conflict and its aftermath. The report acknowledges the UN intervention’s successes in preventing a massacre in Benghazi, protecting civilians, and bringing down the Gaddafi regime. However, it also critically examines the difficulties encountered during the transition to stability, the humanitarian effects of the intervention, and the Libyan conflict’s regional ramifications.

This report aims to contribute to the ongoing discussion regarding the application of the R2P principle by critically analyzing the advantages and disadvantages of the UN’s responsibility to protect Libya. Policymakers, practitioners, and academics involved in conflict prevention, humanitarian intervention, and post-conflict peacebuilding can learn from the findings and recommendations, enabling a more responsible and effective approach to the protection of populations at risk of mass atrocities (Jaymelee J. Kim, 2018).

2.0. Historical Context and Causes of the Libyan Conflict

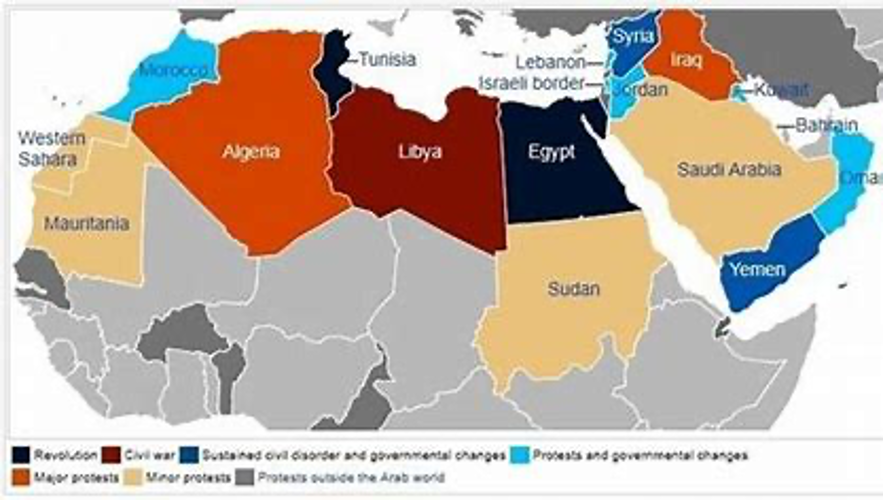

Toward the start of 2011, in the midst of a rush of famous dissent across the Center East and North Africa, to a great extent, quiet fights against immovably settled systems brought about the quick exchange of force in Egypt and Tunisia. In Libya, in any case, an uprising against the four-decade rule of Muammar al-Qaddafi provoked cross-country struggle and overall military intercession.

2.1. Gaddafi’s autocratic regime and suppression of dissent

It is difficult to understand the conflict in Libya without considering Muammar Gaddafi’s autocratic rule, which went on for over forty years. Dissent was suppressed, political freedom was restricted, and authority was centralized under Gaddafi’s rule. Civil society, the political opposition, and independent media were severely repressed, making it hard to have democratic processes or opposing voices. According to Dail & Madsen (2012), the populace’s feelings of fear and discontent were exacerbated by the absence of strong institutions and a culture of accountability.

2.2. Emergence of the Arab Spring and its impact on Libya

The Arab Spring, a rush of favorable to a majority rules government uprisings that cleared across the Center East and North Africa in 2011, gave an impetus to change in Libya (Spierings, 2017). Libyan citizens took to the streets to demand political reforms, greater freedoms, and an end to Gaddafi’s rule, inspired by the successful uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt. The underlying fights were met with a vicious crackdown by security powers, which further filled the discontent and prompted a heightening of the contention.

2.3. The escalation of the Libyan conflict and international response

As different outfitted gatherings, including opposition powers trying to overthrow the Gaddafi system, arose, what started as a famous uprising immediately transformed into a prolonged civil war. Throughout the conflict, tribal militias, Islamist groups, and regional factions all fought for control and power. The global community was faced with a crucial decision regarding how to respond to the increasing brutality and the potential for widespread outrages as the situation deteriorated.

The UN Security Board, through Resolution 1970, denounced the common freedoms violation in Libya and forced sanctions on the Gaddafi system (Alston, 2016). Hence, Goal 1973 approved the utilization of all vital means to safeguard regular folks and lay out a restricted air space. This resolution marked a significant application of the Responsibility to Protect principle because it provided the legal foundation for the intervention of a coalition of nations led by NATO.

The belief that swift action was required to safeguard the Libyan population’s fundamental rights and prevent a potential massacre of civilians drove the intervention in Libya. Under the UN’s direction, the international community employed military force to support the Libyan people’s aspirations for a democratic and inclusive society and uphold the Responsibility to Protect principle.

The historical context of Gaddafi’s autocratic rule, the rise of the Arab Spring, and the heightening of the contention give significant foundation data to understand the causes and elements of the Libyan conflict (Pruitt, 2009). In order to evaluate the benefits and drawbacks of the UN’s implementation of the Responsibility to Protect principle in Libya, this comprehension is necessary. By examining the historical setting, we can acquire bits of knowledge about the fundamental factors that added to the ejection of the contention and the ensuing global reaction.

3.0 UN Intervention and Application of the Responsibility to Protect in Libya

3.1. Authorization and justification for intervention

The UN mediation in Libya was approved by UN Security Gathering Goal 1973, which required the security of regular folks and approved the utilization of all fundamental means to uphold a restricted air space and shield regular citizens from Gaddafi’s powers. The Responsibility to Protect principle, which asserts the international community’s responsibility to intervene when a state fails to protect its population from mass atrocities, provided justification for the resolution.

The authorization of military intervention in Libya marked a significant application of the Responsibility to Protect principle as a collective international response to a rapidly deteriorating situation and the possibility of widespread human rights violations. Human rights were upheld, civilians were safeguarded, and a humanitarian catastrophe was avoided as the United Nations intervened.

3.2. Implementation of measures to protect civilians

Different measures to shield Libyan regular civilians were carried out by the Unified Countries, NATO, and provincial accomplices (Henderson, 2011). Among these measures were targeted airstrikes against Gaddafi’s military assets to diminish his capabilities and deter attacks on civilian areas, the establishment of a no-fly zone to prevent Gaddafi’s forces from carrying out airstrikes against civilian areas, and the imposition of an arms embargo to limit the flow of weapons into the conflict.

Specifically in the city of Benghazi, where Gaddafi’s powers had gathered and represented a huge danger, the burden of a restricted air space assumed a pivotal part in safeguarding regular people. By preventing Gaddafi’s air force from carrying out indiscriminate attacks, the no-fly zone provided a level of security and protection for the civilian population (Siordet, 1968). Additionally, the targeted airstrikes against Gaddafi’s forces weakened his military and restricted his capacity to commit widespread human rights violations.

3.3 Coordination with NATO and regional actors

NATO and other regional players were closely involved in the UN intervention in Libya. NATO expected a main job in carrying out the tactical parts of the mediation, with part states contributing airplanes and assets to implement the restricted air space and direct airstrikes. The territorial association, the Bedouin Association, likewise assumed a huge part in supporting the mediation and giving authenticity to the global activity.

In terms of ensuring the intervention’s effectiveness and gaining broad international support, coordination with NATO and regional actors was essential. The contribution of territorial entertainers, especially the Middle Easterner Association, assisted with moderating worries of Western mediation and gave a local support to the mediation, improving its authenticity according to the worldwide local area.

3.4 Assessment of the effectiveness of the intervention

The UN’s mediation in Libya, under the sponsorship of the Obligation to Safeguard standard, had both positive results and difficulties. The timely implementation of the no-fly zone and targeted airstrikes were successful in preventing a potential massacre in Benghazi in terms of protecting civilians (Kimani, 2006). As a result of the intervention, the opposition forces were able to regain control, and, in the end, the Gaddafi regime was overthrown. This was accomplished by providing a degree of security and deterrence.

However, the wider objectives of stabilization, institution-building, and long-term peacebuilding should be considered in addition to the immediate protection of civilians when evaluating the intervention’s effectiveness. As will be discussed in the following sections of this report, despite the intervention’s success in protecting civilians, there was no comprehensive post-conflict plan. As a result, the transition period was difficult.

While the intercession accomplished its quick unbiased of safeguarding regular citizens and adding to the defeat of the Gaddafi system, the drawn-out suggestions and results of the mediation have been likely to discussion and analysis (Dretler, 1998). Beyond the immediate protection of civilians, a comprehensive evaluation of the outcomes and impacts of the UN intervention in Libya is required for its evaluation.

4.0. Protection of Civilians: Successes and Challenges

4.1 Timely imposition of the no-fly zone and targeted airstrikes

One of the vital accomplishments of the UN mediation in Libya was the opportune burden of the restricted air space and the execution of focused on airstrikes. Gaddafi’s air force was effectively prevented from launching indiscriminate airstrikes against civilian areas by the no-fly zone, preventing potential mass atrocities. The intervention provided a significant amount of protection for the civilian population by grounding Gaddafi’s air force, particularly in cities like Benghazi, which faced an immediate threat from Gaddafi’s forces.

Targeted airstrikes against Gaddafi’s military assets, in addition to the no-fly zone, were crucial in reducing his capabilities and preventing attacks on civilian areas (Geohring, 2020). By killing key army bases and upsetting Gaddafi’s order and control framework, the airstrikes debilitated his capacity to do boundless denials of basic liberties against regular citizens. Both a degree of security for the general public and the prevention of a potential massacre were achieved through these measures.

4.2. Prevention of a potential massacre in Benghazi

The UN mediation in Libya assumed a critical part in preventing a likely massacre in the city of Benghazi. Before the intercession, Gaddafi’s powers had encircled Benghazi, and there were fears that a fierce attack on the city was inescapable. Gaddafi’s forces were disrupted by the imposition of the no-fly zone and the targeted airstrikes, allowing the opposition to regroup and defend the city.

The ideal mediation deflected a helpful fiasco, saved endless lives, and gave a feeling of safety to the populace in Benghazi. The ability of the international community to take decisive action to protect vulnerable populations at risk of mass atrocities is demonstrated by the fact that preventing a potential massacre in Benghazi became a significant success of the UN’s responsibility to protect in Libya.

4.3 Humanitarian Concerns and unintended consequences

Although the intervention carried out by the United Nations in Libya was successful in protecting civilians, it also resulted in a number of humanitarian issues and unintended outcomes. Blow-back and regular citizen losses happened because of the tactical intercession, especially the airstrikes. Despite the intervention’s stated goal of protecting civilians, unintended harm was done to innocent civilians on the ground.

Additionally, the intervention contributed to the region’s destabilization and the spread of weapons. Not only did the vast arsenals that various armed groups in Libya had access to exacerbate the internal conflict, but they also had spillover effects, causing instability in neighboring nations. The intervention’s unintended effects emphasize how important it is to carefully consider the long-term effects of military actions taken to protect civilians.

4.4 Long-term impact on civilian protection and human rights

The Long-term effect of the UN mediation on nonmilitary personnel assurance and common freedoms in Libya has been blended. Although the intervention initially prevented a massacre and protected civilians, the subsequent political instability and ongoing conflict have made it difficult to maintain long-term civilian protection.

The shortfall of compelling administration structures, the expansion of outfitted state armies, and the absence of safety area change have frustrated endeavors to guarantee the well-being and security of the nonmilitary personnel populace. Reports of common freedoms like torture, extrajudicial killings, and arbitrary detainments continue, featuring the hardships in laying out and maintaining basic liberties principles in Libya since the mediation.

As far as long-haul regular citizen insurance and basic liberties, the progress of the UN’s liability to safeguard Libya relies upon the goal of the fundamental administration and security issues. The foundation of responsible establishments, the improvement of law and order, and the advancement of regard for common freedoms are fundamental parts. To address these issues and create a safe haven for civilians, the United Nations and the international community must keep working with Libyan stakeholders.

5.0 Transition to Stability: Challenges and Shortcomings

The change to strength in Libya following the mediation has been laden with hardships and weaknesses. The absence of a complete post-struggle plan, political divisions, and the discontinuity of equipped gatherings have hampered endeavors to lay out an administration framework that is both steady and comprehensive. The proliferation of armed militias and the absence of effective security sector reform exacerbate the country’s instability and insecurity. The worldwide local area’s restricted commitment to supporting the change and the inability to address basic political and financial complaints have obstructed progress toward long-haul solidness.

6.0 Humanitarian Implications and Regional Impacts

The humanitarian and regional effects of the United Nations’ intervention in Libya were significant. The military intervention caused unintended harm, including civilian casualties and collateral damage, despite its intention to safeguard civilians. A humanitarian crisis has resulted in extensive displacement, limited access to basic services, and a deteriorating humanitarian situation as a result of the continuous fighting and political unrest. The destabilization of Libya has likewise had local outcomes, including the expansion of weapons, the ascent of fanatic gatherings, and the inundation of outcasts and transients across the Mediterranean. The regional effects of the Libyan conflict emphasize the interconnectedness of crises and the necessity of a coordinated regional response to conflict and instability’s challenges.

7.0 Regional Implications and Spill-over Effects

7.1 Destabilization of neighboring countries

The UN mediation in Libya had critical provincial ramifications, especially as far as weakening adjoining nations. The expelling of the Gaddafi system and the following power vacuum established a climate of flimsiness, which straightforwardly affected adjoining nations like Tunisia, Egypt, and Niger (Xirouchaki, 2004). The cross-border movement of weapons and fighters contributed to the spread of violence and the worsening of existing conflicts in these areas. The destabilization of adjoining nations highlighted the interconnectedness of territorial security and the requirement for an exhaustive way to deal with address the aftermath of the Libyan clash.

7.2 Rise of transnational terrorist organizations

The power vacuum and the accessibility of weapons in post-intervention Libya made rich ground for the climb of transnational mental aggressor affiliations. ISIS and al-Qaeda, for example, utilized the condition of turmoil in the country to lay out a presence and take advantage of ungoverned regions. The exercises of these gatherings not just represented an immediate danger to Libya’s security, but, they likewise affected the dependability of the locale and had an impact that spread all through it. The rise of transnational oppressor groups based on fear highlighted the need for vigorous counterterrorism efforts and local participation to address common security issues.

7.3 Challenges in regional security and counterterrorism efforts

Regional security and anti-terrorism efforts faced significant obstacles as a result of Libya’s destabilization and the rise of transnational terrorist groups. Adjoining nations were confronted with the undertaking of getting their boundaries, dealing with the progression of arms and contenders, and forestalling the spread of fanatic belief systems. It was difficult to control the movement of weapons and combat the activities of terrorist groups in Libya because of the porous borders and the absence of effective governance. Because of the strain on regional security forces, countries had to work together to deal with the same threats and improve their counterterrorism efforts.

7.4 Lessons for regional cooperation and preventive diplomacy

The regional implications of the Libyan struggle featured the significance of local participation and preventive discretion in tending to clashes and their overflow impacts (Sapsai,2022). In order to mitigate the security threats posed by Libya, it became clear that joint border management, collaboration in intelligence gathering, and information sharing were required. The mediation and facilitation of dialogue among the various stakeholders was greatly helped by regional organizations like the African Union and the Arab League. The lessons learned from the Libyan conflict emphasized the necessity of proactive regional engagement, early warning mechanisms, and preventive diplomacy to deal with conflicts and the potential regional repercussions they may have.

8.0 Lessons Learned

8.1 Coordinated approach among UN, regional organizations, and stakeholders

The conflict in Libya demonstrated that the United Nations, regional organizations, and relevant stakeholders needed to work together. An extensive reaction to struggle circumstances requires the aggregate endeavors of global, territorial, and nearby entertainers. More noteworthy coordination, data sharing, and joint effort can prompt a more powerful and comprehensive methodology in safeguarding regular people and tending to the underlying drivers of struggles (McMichael,1988).

8.2 Comprehensive post-conflict planning and institution-building

The Libyan intervention demonstrated how crucial comprehensive post-conflict planning and the establishment of new institutions are. A well-thought-out plan for stabilizing the nation, promoting inclusive governance, and addressing security sector reform must accompany military interventions. To avoid future conflicts and ensure long-term peace, the international community ought to give long-term planning top priority.

8.3 Balancing military action with political solutions

The military mediation in Libya showed the significance of offsetting military activity with political arrangements, notwithstanding the way that it assumed an essential part in safeguarding regular folks. With the ultimate goal of facilitating an inclusive dialogue and political transition, the intervention ought to be viewed as a means to an end. Diplomatic efforts ought to be given top priority, and political processes ought to be supported in order to steer clear of conflict escalation and promote long-term solutions.

9.0 Conclusion:

The responsibility that the United Nations has to protect Libya, as demonstrated by the 2011 intervention, had both successes and difficulties. The no-fly zone was put in place at the right time, and targeted airstrikes protected civilians and stopped a possible massacre in Benghazi. In any case, challenges arose during the progress time frame and in the territorial setting, including the destabilization of adjoining nations, the ascent of transnational psychological oppressor associations, and difficulties in provincial security and counterterrorism endeavors.

The regional ramifications and overflow impacts of the Libyan clash featured the interconnectedness of territorial security and the requirement for an extensive way to deal with address clashes and their results. The illustrations gained from the Libyan case stressed the significance of provincial participation, preventive discretion, and a planned methodology among the UN, territorial associations, and partners.

Moreover, the illustrations gained from the Libyan intercession give important bits of knowledge and suggestions for future circumstances. These include the need for comprehensive post-conflict planning and institution-building, striking a balance between military action and political solutions, addressing humanitarian issues, and reducing the number of unintended consequences. By executing these suggestions, the worldwide local area can upgrade the viability of the Obligation to Safeguard guideline and work on its capacity to safeguard populations in danger in later contentions.

It is fundamental to perceive that the progress of the UN’s liability to safeguard in Libya isn’t without its intricacies and restrictions. The long-term effects on Libya’s civilian protection and human rights remain mixed, and governance, security, and human rights issues remain problematic (Muinikeks, 2013). To address these issues, ongoing efforts are required, such as fostering an environment free of violence and abuse for civilians, supporting the rule of law, and promoting accountable institutions.

The UN mediation in Libya illustrates, overall, how the Obligation to Safeguard standard can be set in motion. It consolidates the difficulties, results, and depictions experienced nearby, giving critical information to approaching intercessions and attempts to safeguard peoples in peril from colossal monsters. The general region continues to apply what it has seen, change its designs, and collaborate to destroy and answer conflicts while remaining mindful of common open doors and nonmilitary labor force security as key standards.

10.0 References

Alston, P. (2006). Reconceiving the UN Human Rights Regime: Challenges Confronting the New UN Human Rights Council. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.907471

Baughin, W. A. (1989). The Private Civil War: Popular Thought During the Sectional Conflict (review). Civil War History, 35(4), 339–340. https://doi.org/10.1353/cwh.1989.0070

Claes, J. (2012). Protecting Civilians from Mass Atrocities: Meeting the Challenge of R2P Rejectionism. Global Responsibility to Protect, 4(1), 67–97. https://doi.org/10.1163/187598412×619685

Dail, D., & Madsen, L. (2012, September 24). Estimating Open Population Site Occupancy from Presence-Absence Data Lacking the Robust Design. Biometrics, 69(1), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0420.2012.01796.x

Dretler, S. P. (1998, August). CONTEMPORARY UROLOGICAL INTERVENTION FOR CYSTINURIC PATIENTS. The Journal of Urology, 344–345. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005392-199808000-00012

Goehring, J. (2022). The Legality of Intermingling Military and Civilian Capabilities in Space. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4255086

Hackers carry out revenge attacks on Islamic sites. (2001, September). Network Security, 2001(9), 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1353-4858(01)00903-5

Henderson, C. (2011, July). II. INTERNATIONAL MEASURES FOR THE PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN LIBYA AND CÔTE D’IVOIRE. International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 60(3), 767–778. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020589311000315

Jaymelee J. Kim. (2018). An Alternative Approach to Forensic Anthropology: Findings from Northern Uganda. African Conflict and Peacebuilding Review, 8(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.2979/africonfpeacrevi.8.1.02

Kimani, M. (2006, July 31). Protecting civilians from genocide. Africa Renewal, 20(2), 4–5. https://doi.org/10.18356/0486e519-en

McMichael, H. (1988, January). A Holistic Approach to Medical Education Can We Learn to Care More? Holistic Medicine, 3(3), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561828809043590

Muižnieks, N. (2013). The Future of Human Rights Protection in Europe. Security and Human Rights, 24(1), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1163/18750230-02401007

Pruitt, D. G. (2009, March). Escalation and de-escalation in asymmetric conflict†. Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict, 2(1), 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/17467580903214501

Sapsai, A. (2022). DIGITAL DIPLOMACY OF AFRICAN STATES IN GLOBAL AND REGIONAL STRUCTURES OF MULTILATERAL COOPERATION. Scientific Journal “Regional Studies,”31, 129–134. https://doi.org/10.32782/2663-6170/2022.31.24

Siordet, F. (1968, January). Protection of civilian populations against the dangers of indiscriminate warfare. International Review of the Red Cross, 8(82), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020860400000474

Spierings, N. (2017, March 24). Trust and Tolerance across the Middle East and North Africa: A Comparative Perspective on the Impact of the Arab Uprisings. Politics and Governance, 5(2), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v5i2.750

Targeted attacks against military contractors were discovered. (2010, January). Computer Fraud & Security, 2010(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1361-3723(10)70105-6

Welsh, J., & Banda, M. (2010). International Law and the Responsibility to Protect: Clarifying or Expanding States’ Responsibilities? Global Responsibility to Protect, 2(3), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1163/187598410×500363

Xirouchaki, C. (2004, March). Surface nanostructures created by cluster-surface impact. Vacuum, 73(1), 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacuum.2003.12.036

write

write