INTRODUCTION

Universal healthcare coverage remains a pivotal governance challenge balancing equitable access, quality care, and fiscal sustainability across aging populations. Canada’s single-payer public healthcare system has largely succeeded in population health but still needs to improve its quality of care and efficiency. The United Kingdom was selected due to its strong parallels as a pioneer of single-payer universal healthcare alongside Canada. In cases where comparisons are made, they typically highlight particular facets of the system, like spending, cancer treatment, or quality, and present an inconsistent image of relative effectiveness.

Fortunately, during the past few years, new national data have become available, enabling a thorough comparison of health system performance, including access, quality, and outcomes, in addition to spending. There needs to be more comparative data on the UK’s performance about other high-income nations across several critical metrics.(Papanicolas et al., 2019). This UK-Canada comparison concentrates on structural dimensions of otherwise analogous universal single-payer systems seeking high-quality, equitable care for all citizens regardless of socioeconomic status.

Key aspects:

Several significant dimensions offer insights when comparing the NHS to the Canadian healthcare system. The first aspect involves comparing and contrasting the different funding models wherein the UK employs direct tax financing while Canada uses the insurance premium model. Another element is evaluating the scope and accessibility of each system based on what services are covered, such as dental, pharmacy and health equity performance. Benchmarking population health outcomes and quality improvement initiatives is also useful to compare results and innovations. Analyzing centralized workforce oversight and physician resource planning offers insight into how each system handles human capital. (Forest et al., 2018). Finally, assessing data analytics utilization, care coordination mechanisms and overall system governance can showcase relative integration and coordination. Analyzing these key aspects through the NHS and Canada comparative analysis framework can reveal strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities to improve each country’s healthcare system.

OVERVIEW OF UK HEALTHCARE SYSTEM

Introducing US Healthcare System:

The United Kingdom’s healthcare system centers around the taxpayer-funded National Health Service (NHS), which has provided universal coverage for all UK residents since 1948 (Maruthappu et al., 2018). NHS is the highest employer in UK with over 1.6 million people (headcount) as of 2023. Across hospital and community health services (HCHS), there were over 1.4 million employees and over 190,000 general medical practice staff. The NHS budget accounts for over 80% of total health spending in the UK, reflecting one of the most government-run healthcare models globally (Piotr Ozierański et al., 2023). The Department’s spending in 2022/23 was £181.7 billion. Most of this expenditure, or £171.8 billion, or 94.6%, went towards regular expenses such as staff salaries and medicines.

Structure:

The NHS system represents a comprehensive single-payer model providing universal health coverage for all permanent UK residents regardless of socioeconomic status, employment, or individual health risk. Healthcare delivery occurs through a decentralized model with power delegated to regional authorities while centralized bodies like NHS England oversee national standards. The basic philosophy of the NHS stipulates universality, accessibility, equity, comprehensiveness, and being free at the point of use for all legally residing UK citizens based on their clinical needs as opposed to the ability to pay (Friebel et al., 2018).

Guiding Principles:

The NHS has already implemented various significant reforms over the last few years to improve the quality of care and access. The setting of maximum wait time targets across the vital segments of health care, such as the limitation of the working hours of the Emergency Department and the quicker scheduling of elective procedures, cancer therapies, and surgery, are among these measures (Siciliani, 2023). The NHS now has to make public reports about hospital infection rates, publish regional clinical quality benchmarking data and conduct surveys on an annual basis on patients’ healthcare services citizens. In order to encourage general practitioners (GPs), the NHS introduced pay-by-performance, which is based on quality-of-care measures that increase health indicators. A move has been taking place to put more emphasis on patient choices over specialist referrals and on personalized access, though there still needs to be a huge disparity in some parts of geography as to what services are locally available based on patient residence. These initiatives are directed toward NHS improvement, quality increase, accountability raising, and patient-centred care.

Notable Features:

The National Health Service (NHS) is the UK’s organ of a tax-funded national health care system that provides services free of charge to the patient at the point of his/ her use. Contrary to most healthcare systems, NHS does not require the payment of insurance premiums or out-of-pocket payments to access services. NHS covers GP services, A&E services, specialist consultations, hospital treatments, mental healthcare, maternity care, rehabilitation services, and care for those with chronic conditions. Some medications, however, have expected charges, but more than 85% of the drugs prescribed in the NHS are covered fully. Resembling the purpose of NHS is to give everybody access to comprehensive healthcare services without having to pay directly for using them.

Primary care is the backbone of the NHS model, with general practitioners (GPs) serving as the first point of contact and care coordinators for patients (Kozlowska et al., 2018). This gatekeeping role aims to maximize prevention and population health management strategies for cost efficiency and bending the cost curve – critical amid budget constraints. Key preventative priorities include GP incentive schemes improving smoking cessation referral rates, obesity management, and community-based chronic disease monitoring. The Quality and Outcomes Framework ties GP reimbursement to evidence-based quality metrics met for common conditions. Since the early 2000s, the NHS has concentrated additional reforms on improving lengthy wait times and uneven cancer care, expanding patient choice from their GP referrals, and increasing accountability on performance (Bar-Haim et al., 2023).

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS

Comparing and Contrasting the Canadian healthcare system with the UK:

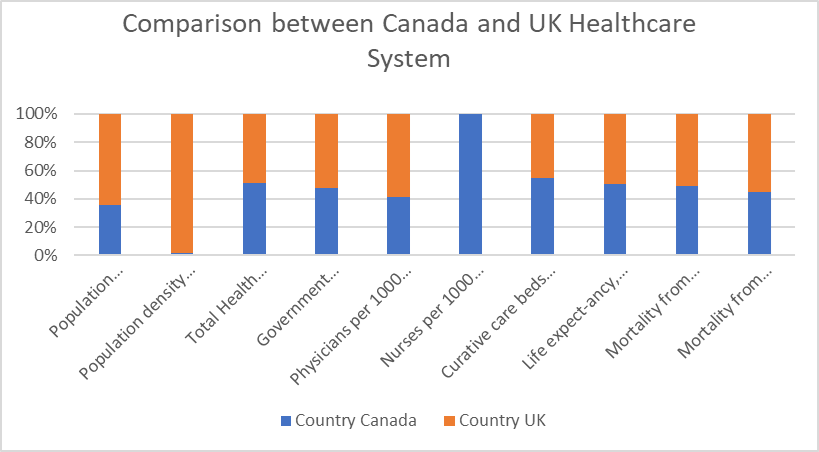

Fundamentally, Canada maintains a more complex public-private delivery system across ten provinces and three territories, whereas the UK system revolves around a consolidated National Health Service (Deber, 2018). This drives more variability in care quality and access in Canada. The UK has almost double the population of Canada, but Canada has a much lower population density, reflecting the UK’s situation as a small, densely-packed country. Furthermore, Canada has a much lower population density at four people per square km compared to 275 for the densely-packed UK. This affects public health determinants like pollution and communicable disease transmission.

Key Metrics:

Accessibility

The people of Canada and the United Kingdom are covered by universal health care. Residents can access essential care without financial limitations. The accessibility barriers about wait times and service availability based on geography, however, differ greatly between the two systems. Compared to the United Kingdom, where wait times for adults 65 years or older are 14%, wait times in Canada are 31% longer than six days. Wait times for specialist care in Canada have remained the same over the past decade (Martin et al., 2018). Canada’s publicly-funded system is renowned for lengthy delays in accessing specialists or undergoing elective procedures, largely from supply shortages relative to demand. Average wait times from primary care referral to treatment can stretch many months depending on the surgery, with Canada at 62%, ranking poorly on Commonwealth Fund timeliness metrics. Significant investment in additional human resources and centralized intake hubs will be essential to ease this pressure point.

Conversely, the UK National Health Service implemented explicit wait time standards and targets over the past 20 years that have tangibly reduced delays for accident, emergency, cancer treatment and elective surgeries to among the best internationally. However, rural patient access challenges persist concerning the availability of GP and specialized services based on the regional distribution of facilities and workforce. While avoiding Canadian-style waiting lists, new models of rural health delivery, including periodic community-based clinics and telehealth support, could aid service gaps for remote UK communities.

Quality of Care:

Regarding quality of care, the UK healthcare system has scored higher on patient-centeredness, consistency of best practice adherence, and process quality (Jarrar et al., 2021). On the other hand, the Canadian system has an established reputation for providing high-quality care, particularly in specialized services such as cancer care, organ transplants, and clinical trials. The UK has more physicians per capita, at 3.91 per 1,000 people, while Canada stands at 2.7. This suggests better healthcare access despite higher demand from higher population levels.

Patient Outcomes:

Based on indicators like life expectancy and maternal mortality, the national health measures of Canada are slightly better than the UK’s (Haim et al., 2021). Currently, Canada’s average lifespan at the time of birth is 82 years, but 81.3 years in the UK. On the contrary, covering amenable mortality with healthcare, the UK prevails over Canada by far, surpassing both preventable and treatable cases, highlighting betterf timely and high-quality care delivery. This might be associated with Canada being among the countries that have maintained a good population-to-facilities ratio – a cleaner environment and lower obesity rate are just some of the health benefits of the population. While these are the systems where the UK shows stronger outcomes, they remain inadequate as per the statistics.

The health of the population is the aggregate of the more complex lifestyle preferences and other social determinants of health and not the healthcare outcomes only. Holding all other factors constant, the wider population, especially in Canada, where population density is acutely low, has beneficial effects concerning pollution reduction, disease transmission, and public health advantages translated into better longevity statistics. Unlike that, the United Kingdom shared more than double-digit leading positions with Canada for all quality of care indicators when they were focusing on each healthcare system individually; they performed significantly better on measures of time, patient-centeredness, and adherence to the practices, respectively. In essence, Canada maintains an edge in wider public health impact, while care delivery performance and mitigation of social barriers favor the UK system. Adopting aspects of UK healthcare governance and quality improvement initiatives could also significantly benefit Canadian patient outcomes.

Health Expenditures:

Total health expenditure as a % of GDP is similar between the two countries (Jakovljevic et al., 2020). However, the UK government accounts for a higher percentage of overall health spending than Canada’s more mixed public-private model. The Canadian system spends almost 11% of its GDP on healthcare, which is higher than the UK’s expenditure of approximately 9.8%. Nevertheless, Canada has higher rates for people who pay out of pocket for health care compared with the UK.

The UK NHS has efficiently contained health care costs, including boosting value-based health care. This is achieved by aligning incentives and promoting innovation. For instance, This c,ould highligh,t that though both countries have increasing spending for ageing pan opulation, the UK’s higher physicians in terms 3.91 per 1000 and lower curative beds 2.5 confers a higher value of 3.87 per 1000 in UK demonthe st,rating better community-based preventative capacity that cuts hospitalization. The UK also notes mortality at 56 per 100,000 owing to the striking difference with the Canadian 69 mortality rate that can be obtained because they signify an improvement in the healthcare system.

One pivotal distinction between the two systems is the UK’s focus on robust system measurement, national outcome targets, and detailed public reporting for accountability (Abhayawansa et al., 2021b). Both UK and Canadian health systems have common challenges characterized by the threats of shortage of funds and resources (Unruh et al., 2022). Both systems find it hard to control budget adjustments, with the expenses topping the growth rate. The consistently rising costs of innovative technologies and the widespread prevalence of chronic diseases which is an outcome of the ageing population, increasing the burden on the healthcare systems. Additionally, suboptimal system integration, induced by workforce shortages, especially in the mental health and primary care areas, makes the problem even worse (Mullan et al., 2023).

In contrast, Canada needs to catch up in establishing comparable quality strategies and transparency systems to drive change. Though the UK and Canada have public health funding systems in place, the UK has incomparable centralized measurement and accountability systems that have been a success compared to the Canadian model. This lack of a comprehensive approach to quality improvement and transparency may contribute to slower progress in addressing certain healthcare challenges.

Figure 1

Note:

Strengths and Weaknesses within the UK and Canadian healthcare systems

Strengths and Weaknesses within the UK healthcare system:

The achievement of truly universal health coverage, which allows all citizens to access necessary care regardless of socioeconomic factors, is one of the UK’s National Health Service’s (NHS) primary strengths. Administrative costs also run substantially lower in a streamlined single-payer structure. The NHS generally demonstrates high performance reflecting system quality on critical health access and outcome metrics like amenable mortality (Bojke et al., 2018). Finally, a wide range of healthcare services are provided, including dental, pharmaceutical, and rehabilitation care.

However, the NHS grapples with extensively long waiting periods for specialist consultations, elective major surgeries, and even emergency department care during times of peak demand. The UK also remains below average on European Union benchmarks for disease prevention quality of care indicators. Workforce limitations including systemic physician and nurse staffing shortages which drive extensive clinician workload strains threaten the sustainability of current access (Lowman et al., 2022). Regarding medications, coverage gaps exist for certain outpatient prescriptions including specialized drugs.

Strengths and Weaknesses within the Canadian healthcare system:

The Canadian healthcare system offers a similar crown jewel through its publicly funded model guaranteeing full financial accessibility for all necessary hospital and doctor services without insurance premiums or out-of-pocket fees at point of use. Robust investments in hospital care and wider primary care accessibility have yielded positive health outcomes and satisfaction (FORD‐GILBOE et al., 2018). Most physician salary rates also rise above international comparisons. Additionally, Canada maintains lower age-standardized chronic disease and cancer mortality rates than the UK.

However, Canada continues to grapple with inferior access, highlighted by extremely protracted wait times for elective procedures like hip replacements and diagnostic imaging services. Serious coverage gaps remain for major categories of healthcare like vision and dental care, therapy/rehabilitation, outpatient medication costs, home care programs, and long-term care outside hospital settings. Shortages in the supply of primary care providers also emerge related to aging physician demographics without coordinated succession plans. Finally, data reveals poorer health outcomes among marginalized populations, including indigenous groups – reflecting the impacts of deep healthcare inequities (Deravin et al., 2018).

GAPS IN CANADIAN HEALTHCARE SYSTEM

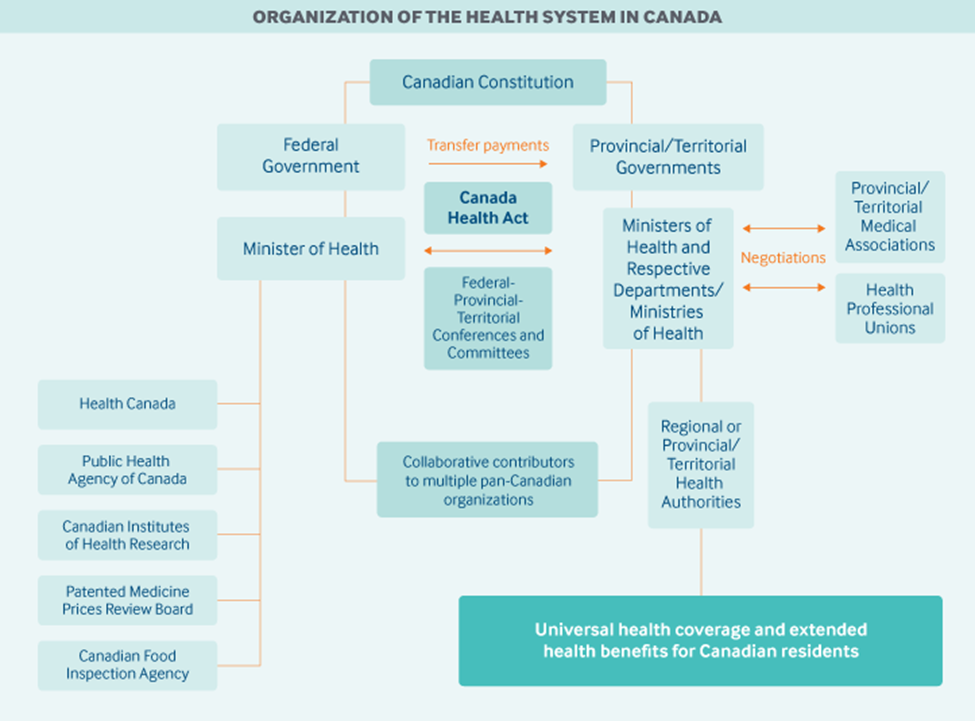

Canada’s provincially administered health systems comprise a mixture of public financing and private providers, leading to fragmentation, gaps in care continuity, and vast inconsistency in access and quality across regions (George, 2020). For example, wait times for specialists or common surgeries can range from weeks to years depending on which province, territory or community a patient resides in rather than actual clinical urgency.

Publicly funded coverage has yet to overcome unequal access stemming from jurisdictional budget variability, health human resource availability and efficiency. Canada needs comparable benchmarking, reporting and transparency on key safety and outcome metrics to highlight community performance gaps (Rabeneck et al., 2023). Further, funding levels float largely independently of the achievement of healthcare quality goals. For example, the UK NHS actively measures, targets and publicly reports hospital readmission rates, preventative care rates by region, and cancer-related mortality to motivate lagging policy and clinical priorities. Canada’s complexity hinders response to ongoing quality deficits and inequities.

Canada’s lack of coordinated health data systems and infrastructure prevents holistic, connected care across the fragmented public-private delivery landscape (Policies et al., 2023). Without robust information sharing between providers, vulnerable patient groups often slip through the cracks, while population health risk stratification fails without big-picture data. A survey found that 85% of Canadian physicians need help accessing hospital visit records, test results or patient medical histories held by other practitioners, facilities and regions – severely hindering informed clinical decision-making and personalization. This contrasts with the NHS’s push towards widespread interoperable electronic health records. Efficiency modelling and the planning of health worker allocation are also unduly complicated by fragmented, uncoordinated datasets (Harris et al., 2019).

Figure 2

Note: Global Healthcare Jobs | Medvocation. (n.d.-c).

https://medvocation.com/en/blog/the-healthcare-system-and-employment-market-in-canadawhat-you-need-to-know/161

The nation has generally achieved universal coverage; however, the system still needs to expand to provide consistently high-quality coordinated care with equal access for all groups, regardless of their social or geographic disadvantage. (Allin et al., 2022). The most recent studies in top journals are raising the caution that there are gaps in the range from 30% of higher deaths due to heart attack among Canadian women and the risk that is three times greater for adverse drug events compared to NHS, which signals a danger around fragmentation. The integrated accountability mechanisms by the NHS highlight tangible models for reform – whether adopting common electronic records exchange standards or transparently reporting stratified quality metrics by region and demographics to motivate localized priorities (Colombo et al., 2020). Within the undeniable scope of quality and equity that prevail in Canadian public coverage, accessibility should be as equal as possible.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR IMPROVEMENT

Implement a national quality management system which connects to leadership responsibility at the province and regional levels:Canada critically needs to have consolidated system-level benchmarks measuring healthcare quality, unlike the UK’s robust NHS outcome reporting (Short et al., 2023). Compared to the UK, where the NHS has a robust outcome reporting system, Canada has a great challenge with healthcare quality benchmarks due to the need for aggregated system-level benchmarks. Rather than simply magnifying funding volumes, public reporting on poor quality metrics stratified by province mapped onto each health authority’s leadership accountability could bring about the needed improvement of outcomes to such a level that it would command absolute accountability for improving the quality metrics. Focusing on policy in the NHS reforms means that even without extra funding, safer treatments and decreased mortality are achieved by enforcing objectively measured and published targets. In addition, centralized data measurement would produce a Canadian model, which is important for overcoming scattered data and deficiencies in coordination.

Ensure that the national strategy of the healthcare workforce is radicalized towards addressing the healthcare vacuum in urban and rural areas:Centrally located national workforce strategy is essential in Canada due to physicians’ constant shortage and geospatial imbalance. Despite regional expansion efforts, challenging delivery issues mainly exist in remote rural and sparsely populated indigenous pockets, necessitating collaborative approaches. Geographic imbalances in physician availability require urgent policy coordination as rural/remote areas face much more severe shortages (World Health Organization, 2018). Centralized health workforce planning models from Australia and the UK have set recruitment targets and financial incentives addressing gap areas rather than leaving disparities to regional variability. Adopting similar national self-sufficiency principles can build workforce equilibrium. The Health Education England NHS Agency presents a prototype that should be applied for national self-sufficiency workforce planning that looks beyond regional political constraints. The setting up of a parity health person workforce oversight mechanism will support an equitable deployment of this cadre by purposeful modelling, forecasting, and placement accountability mechanisms currently lacking.

Invest in health information infrastructure advancement and data analytics technologies capabilities:Harmonized health data systems should be given additional importance to empower patient-centric coordinated care and informed system-wide improvements. Fragmented data analytics hamper monitoring of coverage gaps and intervention impacts. However, standardization and advanced integration of electronic records under centralized bodies like the UK’s National Information Board have powered risk stratification and preventative care at the population scale (French et al., 2020). Canada can make similar investments to turn dispersed data into strategic intelligence. The UK National Health Service’s National Information Board model illustrates how a centralized data infrastructure and governance promotes disease risk stratification at the population scale and implementation of preventative care. Consolidating data frameworks system-wise makes the inequalities from quality gaps and allocation inequities visible and, before that, could be addressed by quick reforms that target the most disadvantaged groups.

CONCLUSION

Universal access to healthcare by the entire population, coupled with the positive health outcomes resulting from Canada‘s single-payer model, has made the model successful. Nevertheless, there are issues concerning continuity of care, accessibility, and quality variance, which are not as satisfactory as the structure of a nationalized healthcare system in the United Kingdom. Analyzing the UK’s NHS’s most recent quality strategies, national accountability, and performance demands implemented recently by focusing on the UK’s consolidated NHS exemplifies what Canadian health practitioners can do to eliminate inequalities and achieve responsiveness to shifting demographics. Both the guidance and the precedents of the NHS are the foundation for the recommendations that now drive policies to achieve prominent access, data interoperability, and coordinated preventative care quality.

While limitations on fiscal resources, aging populations, diversity challenges, and geography exist, comparative analyses help contextualize common pressure points broadly. The perspectives from the key NHS issues include leadership accountability on equity criteria, data-driven agility to community quality slumps, and cross-system coordination as pliable maps to reach both universality and patient-centred care, capturing the entire population. Subsequent economic studies integrating long-term savings remain recommended to spur further mutually aligned policies learning from international innovation.

REFERENCES:

Abhayawansa, S, Adams, C., Neesham, C (2021). Accountability and Governance in Pursuit of Sustainable Development Goals: Conceptualising how governments create value, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal. Vol. 34 No. 4, pp. 923-945 https://drcaroladams.net/accountability-and-governance-in-pursuit-of-sustainable-development-goals-conceptualising-how-governments-create-value/

Allin, S., Campbell, S., Jamieson, M., Miller, F., Roerig, M., & Sproule, J. (2022). Sustainability and Resilience in the Canadian Health System CANADA.

https://phssr.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/WEF_PHSSR_Canada_2022.pdf

Bar-Haim, S., Baraitser, L., & Moore, M. D. (2023). The shadows of waiting and care: on discourses of waiting in the history of the British National Health Service. Wellcome Open Research, 8, 73.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9978246/pdf/wellcomeopenres-8-20970.pdf

Bojke, C., Castelli, A., Grasic, K., Mason, A., & Street, A. D. (2018). Accounting for the quality of NHS output.

https://www.york.ac.uk/media/che/documents/papers/researchpapers/CHERP153_accounting_quality_NHS_output.pdf

Colombo, F., Oderkirk, J., &Slawomirski, L. (2020). Health information systems, electronic medical records, and big data in global healthcare: Progress and challenges in OECD countries. Handbook of global health, 1-31.

https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-030-05325-3_71-1

Deber RB, Zwicker J. Treating Health Care: How the Canadian System Works and How It Could Work Better. Healthc Q. 2018 Oct;21(3):16–18.

http://dx.doi.org/10.12927/hcq.2018.25707

Deravin, L., Francis, K., & Anderson, J. (2018). Closing the gap in Indigenous health inequity–is it making a difference? International nursing review, 65(4), 477-483.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/inr.12436

FORD‐GILBOE, M. A. R. I. L. Y. N., Wathen, C. N., Varcoe, C., Herbert, C., Jackson, B. E., Lavoie, J. G., … & Browne, A. J. (2018). How equity‐oriented health care affects health: key mechanisms and implications for primary health care practice and policy. The Milbank Quarterly, 96(4), 635–671.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1468-0009.12349

Forest, P. G., & Martin, D. (2018). Fit for purpose: Findings and recommendations of the external review of the Pan-Canadian health organizations: Summary report. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada.

https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/reports-publications/health-care-system/findings-recommendations-external-review-pan-canadian-health-organization.html?wbdisable=true

Friebel, R., Molloy, A., Leatherman, S., Dixon, J., Bauhoff, S., &Chalkidou, K. (2018). Achieving high-quality universal health coverage: a perspective from the National Health Service in England. BMJ Global Health, 3(6), e000944.

https://gh.bmj.com/content/bmjgh/3/6/e000944.full.pdf

French, D. P., Astley, S., Brentnall, A. R., Cuzick, J., Dobrashian, R., Duffy, S. W., … & Evans, D. G. (2020). What are the benefits and harms of risk-stratified screening as part of the NHS breast screening Programme? Study protocol for a multi-site non-randomized comparison of BC-predict versus usual screening (NCT04359420). BMC Cancer, 20(1), 1–14.

https://bmccancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12885-020-07054-2

George, B., Christopher. (2020). Fixing an Accident of History: Assessing a Social Insurance Model to Achieve Adequate Universal Drug [nsurance.

https://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/bitstream/handle/10012/15724/Bonnett_Christopher.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

Global Healthcare Jobs | Medvocation. (n.d.-c).

https://medvocation.com/en/blog/the-healthcare-system-and-employment-market-in-canadawhat-you-need-to-know/161

Hiam, L., Minton, J., & McKee, M. (2021). What can lifespan variation reveal that life expectancy hides? Comparison of five high-income countries. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 114(8), 389–399.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/01410768211011742

Harris, D. C., Davies, S. J., Finkelstein, F. O., Jha, V., Donner, J. A., Abraham, G., … & Zhao, M. H. (2019). Increasing access to integrated ESKD care as part of universal health coverage. Kidney international, 95(4), S1-S33.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0085253819300055

Jakovljevic, M., Timofeyev, Y., Ranabhat, C. L., Fernandes, P. O., Teixeira, J. P., Rancic, N., &Reshetnikov, V. (2020). Real GDP growth rates and healthcare spending – comparison between the G7 and the EM7 countries. Globalization and Health, 16(1).

https://globalizationandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12992-020-00590-3

Jarrar, M., Al-Bsheish, M., Aldhmadi, B. K., Albaker, W., Meri, A., Dauwed, M., &Minai, M. S. (2021). Effect of Practice Environment on Nurse Reported Quality and Patient Safety: The Mediation Role of Person-Centeredness. Healthcare, 9(11), 1578.

https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9111578

Kozlowska, O., Lumb, A., Tan, G. D., & Rea, R. (2018). Barriers and facilitators to integrating primary and specialist healthcare in the United Kingdom: a narrative literature review. Future Healthcare Journal, 5(1), 64.

https://doi.org/10.7861/futurehosp.5-1-64

Lowman, G. H., & Harms, P. D. (2022). Addressing the nurse workforce crisis: a call for greater integration of the organizational behaviour, human resource management and nursing literature. Journal of managerial psychology, 37(3), 294–303.

https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JMP-04-2022-713/full/html

Maruthappu M, Marshall DC. Viable funding options for the National Health Service in England. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2018;111(6):189-194.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/0141076818766700

Martin D, Miller AP, Quesnel-Vallée A, Caron NR, Vissandjée B, Marchildon GP. Canada’s universal health-care system: achieving its potential. Lancet. 2018 Apr 28;391(10131):1718-1735.

https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S0140-6736%2818%2930181-8

Mullan, L., Armstrong, K., & Job, J. (2023). Barriers and enablers to structured care delivery in Australian rural primary care. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 31(3). 361–384.

https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12963

Piotr Ozierański, Saghy, E., & Shai Mulinari. (2023). Pharmaceutical industry payments to NHS trusts in England: A four-year analysis of the Disclosure UK database. PLOS ONE, 18(11), e0290022–e0290022.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0290022

Policies, E. O. on H. S. and, Panteli, D., Polin, K., Webb, E., Allin, S., Barnes, A., Degelsegger-Márquez, A., Ghafur, S., Jamieson, M., Kim, Y., Litvinova, Y., Nimptsch, U., Parkkinen, M., Aagren Rasmussen, T., Reichebner, C., Röttger, J., Rumball-Smith, J., Scarpetti, G., Seidler, A. L., &Seppänen, J. (2023). Health and care data: approaches to data linkage for evidence-informed policy. In iris.who.int. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe.

https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/371097/9789289059466-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Papanicolas, I., Mossialos, E., Gundersen, A., Woskie, L., & Jha, A. K. (2019). Performance of UK National Health Service compared with other high-income countries: an observational study. The BMJ, l6326.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6326

Rabeneck, L., McCabe, C., Dobrow, M., Ruco, A., Andrew, M. K., Wong, S., Straus, S. E., Passat, L., Richardson, L., Simpson, C., &Boozary, A. (2023). Strengthening health care in Canada post-COVID-19 pandemic. Facets, pp. 8, 1–10.

https://www.facetsjournal.com/doi/pdf/10.1139/facets-2022-0225

Siciliani, L. (2023). A Review of Policies to Reduce Waiting Times for Health Services across OECD Countries: Waiting Times for Health Services. Nordic Journal of Health Economics, 6(1), 162-181.

https://journals.uio.no/NJHE/article/view/10214/8910

Short, H., Fatima Al Sayah, Churchill, K., Keogh, E., Warner, L., ArtoOhinmaa, & Johnson, J. A. (2023). The use of EQ-5D-5L as a patient-reported outcome measure in evaluating community rehabilitation services in Alberta, Canada. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 21(1).

https://hqlo.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12955-023-02207-w#Abs1

Unruh, L., Allin, S., Marchildon, G., Burke, S., Barry, S., Siersbaek, R., Thomas, S., Selina, R., Andriy, K., Alexander, M., Merkur, S., Webb, E., & Williams, G. A. (2022). A comparison of health policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada, Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States of America. Health Policy, 126(5), 427–437.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016885102100169X?via%3Dihub

World Health Organization. (2018). Imbalances in rural primary care: a scoping literature review emphasizing the WHO European Region.

https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/346351/WHO-HIS-SDS-2018.58-eng.pdf

Yanful, B., Kirubarajan, A., Bhatia, D., Mishra, S., Allin, S., & Di Ruggiero, E. (2023). Quality of care in the context of universal health coverage: a scoping review. Health Research Policy and Systems, 21(1), 1–29.

https://health-policy-systems.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12961-022-00957-5

write

write