Introduction

Organizational learning is how groups, teams, and organizations acquire, create, and apply knowledge to improve performance and adapt to environmental changes (Shipton & Defillippi, 2012). It involves continuously developing skills, insights, and capabilities within the organizational context. In today’s dynamic business landscape, where adaptability and innovation are crucial to success, understanding different learning theories and their implications for organizational learning is crucial. Cognitive Learning Theory (CLT) and Situated Learning Theory (SLT) are prominent approaches that shed light on how individuals and groups learn within organizations. We gain insights into their distinct perspectives and implications by comparing these theories.

The significance of comparing CLT and SLT lies in their differing viewpoints on how learning occurs. CLT emphasizes mental processes, such as perception, memory, and problem-solving, as central to learning (Cobb & Bowers, 1999). It suggests that individuals actively process information, connect, and construct knowledge. In contrast, SLT focuses on the social and contextual aspects of learning. It posits that learning is embedded in the environment’s activities, interactions, and culture and that knowledge is co-constructed through social participation. In this report, I will get deeper into CLT and SLT, analyzing their core tenets, strengths, and weaknesses in the context of organizational learning. We will examine how each theory perceives and contributes to organizational learning and explore its similarities and differences. Furthermore, we will illustrate these concepts with real-world examples from strategy, change management, and innovation articles. By doing so, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of how these theories shape and inform the organizational learning process, ultimately aiding organizations in adapting and thriving in today’s ever-evolving business landscape.

Main Body

Organizational Learning

At its core, organizational learning refers to the collective process through which individuals, teams, and entire organizations acquire, assimilate, and apply knowledge to enhance performance and adapt to changes (Yuan & McKelvey, 2004). It entails the accumulation of facts and the improvement of competencies, insights, and strategies that permit groups to respond effectively to challenges and possibilities. This idea emphasizes that mastering is not restricted to individuals; as a substitute, it permeates the organization’s fabric, influencing its way of life, practices, and typical effectiveness.

Definition and Concept of Organizational Learning

Organizational mastering includes a dynamic cycle of activities. Individuals in the company engage in activities consisting of seeking statistics, experimenting with new tactics, reflecting on experiences, and sharing insights with others (Yuan & McKelvey, 2004). These sports incorporate new information into the organization’s procedures, workouts, and choice-making. This continuous process of getting to know and integrating information allows organizations to evolve to changing occasions, innovate, and optimize their overall performance over time.

Importance of Organizational Learning in Modern Workplaces

In a new, rapid-paced, complex enterprise environment, the importance of organizational learning cannot be overstated. Modern offices are characterized by using speedy technological advancements, shifting market dynamics, and evolving consumer preferences. In this context, groups prioritizing getting to know gain an aggressive side (Shipton, 2006). Here is why organizational getting to know is crucial:

Adaptation to Change

Organizational getting to know equips employees and teams with the capabilities and know-how to navigate and thrive in a constantly changing landscape. It permits companies to proactively reply to market shifts, enterprise disruptions, and rising tendencies.

Innovation and Creativity

Learning fosters a subculture of innovation by encouraging personnel to discover new thoughts, test with novel methods, and undertake the reputation quo (Korthagen, 2010). This subculture of innovation can cause the improvement of groundbreaking merchandise, services, and approaches.

Effective Decision-Making

Learning complements people’s potential to analyze complicated conditions, make informed decisions, and remedy issues collaboratively. This, in turn, improves organizational decision-making and strategic planning (Shipton, 2006). Therefore, organizational getting to know is a dynamic and ongoing procedure that empowers groups to thrive in a hastily changing international. By embracing a subculture of studying, agencies can harness the collective intelligence in their personnel, adapt to challenges, and seize possibilities for growth and innovation. This file will further discover how unique getting-to-know theories, mainly Cognitive and Situated Learning Theories, contribute to and shape organizational gaining knowledge in various contexts.

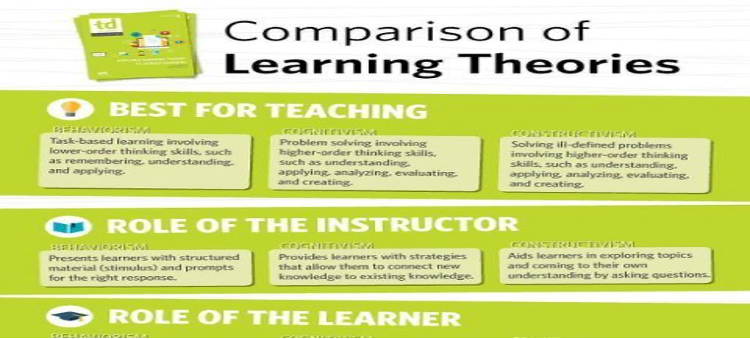

Explanation of Cognitive Learning Theory (CLT) and its Contributions to Organizational Learning

Cognitive Learning Theory (CLT) is a psychological framework that makes a speciality of how people system information, accumulate know-how and develop cognitive abilities. At its core, CLT proposes that getting to know occurs via mental techniques consisting of attention, perception, reminiscence, and problem-fixing. In organizational mastering, CLT shows that people actively interact with facts, make a feel of them, and combine them into their existing mental frameworks (binti Pengiran & Besar 2018). This cognitive engagement ends in purchasing recent abilities, insights, and expertise that contribute to organizational learning. CLT contributes to organizational gaining knowledge by highlighting the importance of cognitive strategies in knowledge acquisition and skill development. It emphasizes that personnel’s questioning patterns, statistics processing skills, and hassle-fixing techniques are widespread in shaping their mastering reports in the agency. CLT also underscores the position of man or woman motivation and self-regulation in riding getting to know, suggesting that employees who are motivated to examine and actively manage their own gaining knowledge of techniques are much more likely to contribute to organizational gaining knowledge of projects (binti Pengiran & Besar 2018).

Examples of CLT in Fostering Organizational Learning

In exercise, CLT can be observed in various organizational mastering tasks. For instance, whilst groups provide education packages encouraging employees to investigate case studies, remedy complex troubles, and engage in critical wondering physical games, they may apply CLT principles. These activities prompt employees to actively system records, make connections, and increase a more profound knowledge of the dependencies. Furthermore, CLT informs the layout of know-how-sharing systems and collaborative spaces inside organizations. By developing environments that facilitate records processing and experience-making, groups allow employees to trade insights, mirror experiences, and together assemble new understandings (Dutta & Crossan, M. M. (2005).

This aligns with CLT’s emphasis on cognitive engagement and energetic getting-to-know. Overall, Cognitive Learning Theory enriches our understanding of how individuals contribute to organizational learning via actively processing records, developing cognitive talents, and leveraging their mental procedures to decorate their personal information and contribute to the collective knowledge of the enterprise (Dutta & Crossan, 2005). This perception has realistic implications for designing effective education programs, expertise-sharing systems and getting-to-know reviews that empower personnel to drive organizational mastering and modelling.

Explanation of Situated Learning Theory (SLT) and its Contributions to Organizational Learning

Situated Learning Theory (SLT) is a gaining knowledge of framework that emphasizes the importance of social and contextual elements in gaining knowledge of the method. According to SLT, learning is not always wholly a character pastime but a collaborative undertaking that takes place inside particular contexts and through lively participation. In organizational mastering, SLT suggests that expertise and abilities are fine received through engagement in authentic responsibilities, participation in groups of practice, and immersion inside the organizational culture (Henning, 2004). SLT highlights the role of interaction, collaboration, and shared practices in shaping and mastering stories and facilitating the integration of knowledge into realistic contexts. SLT’s contributions to organizational gaining knowledge are considerable. It underscores the price of making environments where personnel can engage in actual-world sports and trouble-fixing, mirroring the challenges they stumble upon in their work. This method bridges the distance between theoretical understanding and practical application, allowing employees to develop abilities directly relevant to their roles and responsibilities. SLT also promotes improving a sense of identity and belonging inside the employer, as people become energetic participants of communities of exercise and interaction in shared mastering stories (Henning, 2004).

Examples of SLT in Fostering Organizational Learning

One outstanding instance of SLT in organizational learning is the idea of “on-the-process” or experiential mastering (Fox, 2002). When agencies encourage personnel to analyze through hands-on reports guided by more excellent and skilled colleagues, they use SLT standards. For instance, apprenticeships, mentoring programs, and process shadowing opportunities create possibilities for novices to examine from professionals and benefit sensible insights immediately applicable to their roles. Additionally, SLT informs the practice of creating communities of practice within organizations. These communities unite individuals with shared interests or responsibilities, fostering a collaborative learning environment where members can exchange knowledge, share experiences, and collectively solve challenges. This approach aligns with SLT’s emphasis on social interaction and learning through participation in a supportive community (Fox, 2002). In summary, Situated Learning Theory enriches our understanding of organizational learning by highlighting the pivotal role of context, social interaction, and practical engagement in the learning process. By incorporating SLT principles, organizations can design learning experiences that bridge the gap between theory and practice, foster collaboration, and empower employees to effectively apply their knowledge and skills within the complex and dynamic organizational context.

Similarities between CLT and SLT concerning Organizational Learning

Both Cognitive Learning Theory (CLT) and Situated Learning Theory (SLT) share some commonalities in their perspectives on organizational learning (Leonard, 2002). Both theories recognize that learning is an active process involving engagement and participation rather than passive absorption of information. They emphasize the importance of context, albeit in different ways: CLT considers the individual’s cognitive context and mental processes, while SLT focuses on the social and cultural context within which learning occurs. Additionally, both CLT and SLT acknowledge the significance of motivation in driving learning. Whether it is the intrinsic motivation to construct mental models (CLT) or the motivation stemming from engagement in meaningful tasks and communities (SLT), both theories recognize that motivated learners are more likely to contribute to organizational learning (Mandl & Kopp, 2005).

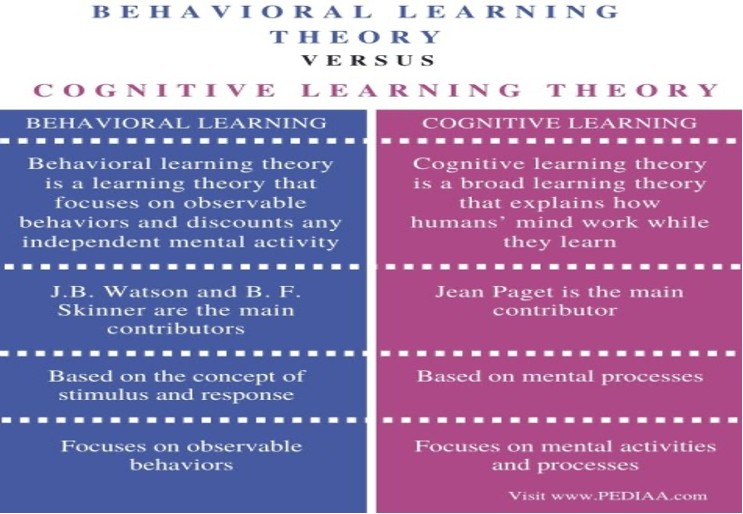

Differences between CLT and SLT regarding Organizational Learning

While there are similarities, CLT and SLT differ fundamentally in their approaches to organizational learning. CLT emphasizes internal cognitive processes such as attention, memory, and problem-solving as central to learning. It focuses on the individual’s mental construction of knowledge and skills. In contrast, SLT emphasizes the external context, social interactions, and participation in communities of practice. It posits that learning is situated in the activities and relationships of the organizational environment. CLT primarily views learning as an individual’s internal mental development, whereas SLT sees it as a collaborative and socially mediated process (Mandl & Kopp, 2005).

Strengths and Weaknesses of CLT and SLT in the Context of Organizational Learning

CLT’s strength lies in its emphasis on cognitive processes, which can lead to deep understanding and critical thinking. It provides a framework for developing and assessing individual cognitive skills. However, it could need to remember the social and contextual components that shape learning within organizations, doubtlessly limiting its applicability to real-international organizational challenges. Alternatively, SLT’s electricity lies in its reputation for the social nature of gaining knowledge (Cobb & Bowers, 1999). It promotes supportive groups and software for studying in realistic contexts. This aligns nicely with the collaborative nature of many organizational tasks. However, SLT’s heavy reliance on context may make it hard to use universally, and it may no longer absolutely cope with improving complicated cognitive skills.

Applications of CLT and SLT in Strategy-as-Practice

In Strategy-as-Practice, Cognitive Learning Theory (CLT) and Situated Learning Theory (SLT) provide beautiful insights into how individuals and agencies can develop strategic thinking and decision-making abilities (Cobb & Bowers, 1999).

CLT and Strategic Learning

CLT suggests that individuals interact in cognitive tactics, including evaluation, assessment, and synthesis, whilst gaining knowledge. Applying CLT to strategic gaining knowledge, businesses can design education packages that inspire personnel to severely assess marketplace developments, analyze aggressive landscapes, and make informed strategic choices (Tripp, 1993). CLT’s recognition of intellectual processes can decorate employees’ potential to understand complex strategic concepts, facilitating their strategic questioning competencies.

SLT and Strategic Learning

Situated Learning Theory, then again, emphasizes the significance of learning inside actual contexts and thru social interactions. In the context of strategic gaining knowledge, SLT indicates that personnel need to be actively involved in real strategic sports, which includes collaborating in strategy development meetings or engaging in cross-useful collaboration. This approach permits personnel to learn from skilled strategists and immerse themselves inside the realistic software of strategic standards, fostering deeper information of strategy-as-practice (McLellan, 1996).

Examples and Strengths/Weaknesses

An instance of the CLT method should involve an online path that publications employees via simulated strategic selection-making scenarios, allowing them to investigate market facts and formulate strategies based totally on cognitive tactics. A power of CLT here is its attention to a person’s cognitive development, enhancing personnel’s analytical talents. However, a weakness will be that it cannot capture the complexities of real-global strategic dynamics. In contrast, an SLT-based method may involve developing approach workshops in which personnel collaborate in move-functional groups to broaden accurate strategic plans. The strength of SLT lies in its emphasis on social interplay, facilitating understanding exchange among employees with numerous expertise (Herrington & Oliver, 1995).

Applications of CLT and SLT in Change in Organizations

When dealing with alternate inside organizations, each Cognitive Learning Theory (CLT) and Situated Learning Theory (SLT) provide precious insights into how individuals and teams can correctly navigate and adapt to organizational transitions.

CLT’s Perspective on Change Learning

CLT emphasizes the man or woman’s cognitive processes in learning, which may be extended to change management. CLT shows that employees want to manner new data in alternate initiatives, recognize the rationale behind adjustments, and examine their implications. Organizations can leverage CLT by supplying clean and comprehensive conversation about the change, offering schooling to enhance employees’ cognitive know-how of the exchange, and developing opportunities to mirror on and speak the alternate (Clancey, 1995). CLT’s recognition of intellectual techniques aids employees in comprehending the motives for alternate and aligning their wondering with new instructions.

SLT’s Perspective on Change Learning

Situated Learning Theory emphasizes the importance of gaining knowledge within the context of authentic activities and through social interactions. In the context of change, SLT suggests that employees should engage in hands-on experiences related to the change, collaborate with colleagues to share insights and problem-solving strategies, and actively participate in the change process (Hedegaard, 1998). Organizations can foster a supportive learning environment where employees collectively adapt and contribute to the change by creating communities of practice or cross-functional teams focused on change implementation.

Examples and Strengths/Weaknesses

An example of applying CLT to change could involve workshops focusing on explaining the rationale behind a change and using cognitive techniques to help employees understand and internalize the need for change. CLT’s strength here is its emphasis on individual cognitive processing, enhancing employees’ clarity on the change (Orey & Nelson, 1994). However, a limitation could be that it might need to pay more attention to the change’s social and emotional dimensions. In summary, combining CLT and SLT principles in change management can create a comprehensive approach that addresses cognitive and social learning aspects during organizational transitions. CLT ensures employees understand the reasons behind the change, while SLT promotes experiential learning and collaboration, enabling organizations to manage change and build a resilient workforce effectively.

Applications of CLT and SLT in Innovation in Organizations

In fostering innovation within businesses, both Cognitive Learning Theory (CLT) and Situated Learning Theory (SLT) provide one-of-a-kind perspectives on inspiring innovative questioning, hassle-fixing, and improving the latest thoughts.

Applying CLT to Organizational Innovation

CLT’s awareness of cognitive strategies can inform techniques to promote innovation. Organizations can observe CLT principles by providing training and workshops that beautify employees’ creative wondering abilities, inspire brainstorming, and provide gear for the concept era (Shipton & Defillippi, 2012). CLT suggests that employees may be guided via tactics such as reading marketplace traits, figuring out unmet wishes, and envisioning revolutionary solutions. By nurturing cognitive capabilities associated with innovation, CLT contributes to a staff better geared to generate and broaden novel ideas.

Applying SLT to Organizational Innovation

Situated Learning Theory’s emphasis on getting to know thru participation and engagement may be harnessed to foster innovation. Organizations can create innovation-targeted communities of practice or challenge teams in which employees from diverse backgrounds collaborate to address innovation challenges. SLT indicates that by means of immersing personnel in real innovation initiatives and offering opportunities for shared problem-solving, agencies can decorate the improvement of innovative ideas via social interplay and contextual mastering (Dutta & Crossan, 2005).

Examples and Strengths/Weaknesses

An example of using CLT for innovation would involve workshops that guide employees through creative concept-era sporting activities, drawing on cognitive strategies to stimulate innovative questioning (Korthagen, 2010). CLT’s power lies in its cognizance of enhancing individual cognitive abilities, fostering a lifestyle of innovative wondering. However, a capacity hindrance can be that it can now only partially cope with the sensible challenges of imposing and scaling progressive ideas. In contrast, an SLT-based total approach to innovation may want to involve go-useful innovation teams running collectively on real innovation tasks. SLT’s power emphasizes collaboration and contextual getting to know, allowing personnel to pool various views and reviews to generate progressive answers (Cobb & Bowers, 1999). Combining elements of each CLT and SLT can create a robust method for fostering innovation inside corporations. CLT complements a man or woman’s cognitive talents to force creative wondering, while SLT leverages social interactions and contextual gaining knowledge to facilitate the development and implementation of modern thoughts. By integrating these theories, agencies can domesticate an innovation subculture that harnesses cognitive and collaborative prowess, driving sustained innovative increase.

Conclusion

In this report, I have mentioned organizational learning, exploring the contributions of Cognitive Learning Theory (CLT) and Situated Learning Theory (SLT) to three critical organizational topics: Strategy-as-Practice, Change Management, and Innovation. Through our analysis, several key insights have emerged, underscoring the fee of integrating those theories for a holistic method of organizational getting to know. I began through expertise the importance of organizational getting to know as a non-stop manner of expertise acquisition and application. I then examined CLT’s emphasis on cognitive techniques and SLT’s awareness of social interactions in the context of organizational getting to know. Both theories offer precise views that contribute to well-rounded information on how individuals and teams study inside organizations. CLT’s strengths lie in its advertising of crucial questioning, problem-solving, and man or woman talent development (Clancey, 1995).

It presents a foundation for deep cognitive understanding. On the other hand, SLT excels in selling collaboration, experiential getting to know, and the software of know-how in real-global contexts. It emphasizes the social dimensions of mastering, fostering groups of practice and sharing getting-to-know reviews. Looking in advance, the integration of CLT and SLT has promising implications for studies and exercises in organizational getting to know. Future studies could explore hybrid tactics that leverage both theories to lay out tailored learning interventions. Practitioners can strategically integrate CLT and SLT concepts to create complete learning studies that cater to various getting-to-know styles and organizational contexts.

Furthermore, the software of these theories could amplify beyond the subjects mentioned in this file, influencing regions including leadership development, worker schooling, and expertise control (Leonard, 2002). In conclusion, as groups hold to evolve in a dynamic and ever-converting landscape, the synergy between Cognitive Learning Theory and Situated Learning Theory offers a robust framework for nurturing effective organizational getting to know. By spotting the cost of both cognitive and social dimensions, organizations can create environments that foster non-stop increase, innovation, and version, in the long run positioning themselves for long-term success in an unexpectedly evolving global enterprise.

References

Binti Pengiran, P. H. S. N., & Besar, H. (2018). Situated learning theory: The key to effective classroom teaching? HONAI, 1(1).

Clancey, W. J. (1995, December). A tutorial on situated learning. In Proceedings of the international conference on Computers and Education (Taiwan) (pp. 49–70).

Cobb, P., & Bowers, J. (1999). Cognitive and situated learning perspectives in theory and practice. Educational researcher, 28(2), 4–15.

Cobb, P., & Bowers, J. (1999). Cognitive and situated learning perspectives in theory and practice. Educational researcher, 28(2), 4–15.

Dutta, D. K., & Crossan, M. M. (2005). The nature of entrepreneurial opportunities: Understanding the process using the 4I organizational learning framework. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(4), 425-449.

Fox, S. (2002). Studying networked learning: Some implications from socially situated learning theory and actor-network theory. In Networked learning: Perspectives and issues (pp. 77–91). London: Springer London.

Hedegaard, M. (1998). Situated learning and cognition: Theoretical learning and cognition. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 5(2), 114-126.

Henning, P. H. (2004). Everyday cognition and situated learning. Handbook of research on educational communications and technology: A project of the association for educational communications and technology, 829-861.

Herrington, J., & Oliver, R. (1995). Critical characteristics of situated learning: Implications for the instructional design of multimedia. In ASCILITE 1995 Conference.

Korthagen, F. A. (2010). It situated learning theory and the pedagogy of teacher education: Towards an integrative view of teacher behaviour and teacher learning. Teaching and teacher education, 26(1), 98-106.

Korthagen, F. A. (2010). It situated learning theory and the pedagogy of teacher education: Towards an integrative view of teacher behaviour and teacher learning. Teaching and teacher education, 26(1), 98-106.

Leonard, D. C. (2002). Learning theories: A to z: A to Z. ABC-CLIO.

Mandl, H., & Kopp, B. (2005). Situated learning: Theories and models. Making it relevant. Context-based learning of science, 15-34.

McLellan, H. (1996). Situated learning perspectives. Educational Technology.

Orey, M. A., & Nelson, W. A. (1994). Situated Learning and the Limits of Applying the Results of These Data to the Theories of Cognitive Apprenticeships.

Shipton, H. (2006). Cohesion or confusion? Towards a typology for organizational learning research 1. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8(4), 233–252.

Shipton, H., & Defillippi, R. (2012). Psychological Perspectives in Organizational Learning: A Four‐Quadrant Approach. Handbook of organizational learning and knowledge management, pp. 67–81.

Tripp, S. D. (1993). Theories, traditions, and situated learning. Educational technology, 33(3), 71–77.

Yuan, Y., & McKelvey, B. (2004). Situated learning theory: Adding rate and complexity effects via Kauffman’s NK model. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 8(1), 65–101.

write

write