Introduction

Over the past forty years, the reform of state-owned enterprises (SOE) has been a critical component of China’s economic reform agenda. During the centralized planning regime, SOEs were the foundation of China’s economy; their restructuring is the most visible of the transformations in China’s enterprise network that have occurred in concert with other institutional and legal reforms in the transformation to a market-based economy. The extent of the SOE economy has shrunk as market-oriented growth has developed. Unlike what transpired in Europe’s former socialist nations, China’s SOE reform did not include broad and rapid privatization (Grimsditch, 2015). The tremendous economic, social, and political ramifications of splitting up SOEs in a short time without establishing the essential circumstances for revolution have long been recognized by China’s reformers (Jefferson, 2016). As a result, China’s economic shift is known for its gradualist and experimental reform strategy, with SOE reform being a classic case. The Chinese government has often said that the primary goal of market-oriented reforms is to create a socialist market economy with the state-owned sector as the leading sector. This way of thinking and acting has had a significant impact on the outcome of earlier SOE reforms and the course of future SOE improvements. Therefore, this essay seeks to examine the main characteristics of the reforms and developments of China’s SOEs, including their contribution to overall economic growth.

Deregulation of SOEs

The Chinese government has long been on the reform path. Reforms that were initiated in the early 1980s laid the foundation for China’s financial take-off for the past twenty years or so (Song, 2018). The establishment of a market economy was one of the first reforms made in China’s socialist society, leading to a significant privatization process. However, there were some state-owned enterprises left in operation at that time. Their role in China’s planned economy had been an important source of discontent among many people (Huang & Jing, 2019). According to Song (2016), the economic reforms implemented in the 1980s successfully brought about several changes. First, there was progress toward a market-oriented economic system. Beijing’s efforts contributed significantly to implementing China’s reform strategy, including SOE reforms (Grimsditch, 2015). Second, there was substantial progress in institutional development. Major institutions such as central banks, commercial banks, and tax authorities were established under a new system (Putterman & Xiao-Yuan, 2000). Third, there was significant progress with regard to technological development and learning opportunities for China’s firms (Song 2016).

The significant policy changes that have been implemented for the past twenty years and more have involved changing the state’s role in various key economic sectors and encouraging private firms to get involved (Grimsditch, 2015). The goal is to transform China’s economy from a planned economy with significant state involvement to a market system in which economic growth is driven by private firms seeking profits and fulfilling their social responsibilities (Song 2016). The process of transforming SOEs is complex. The shift from a strategic economy to a market economy involves the transformation of the role of SOEs in China as well as their relationship to the state, among other things such as the financial system and labor market (Huang & Jing, 2019).

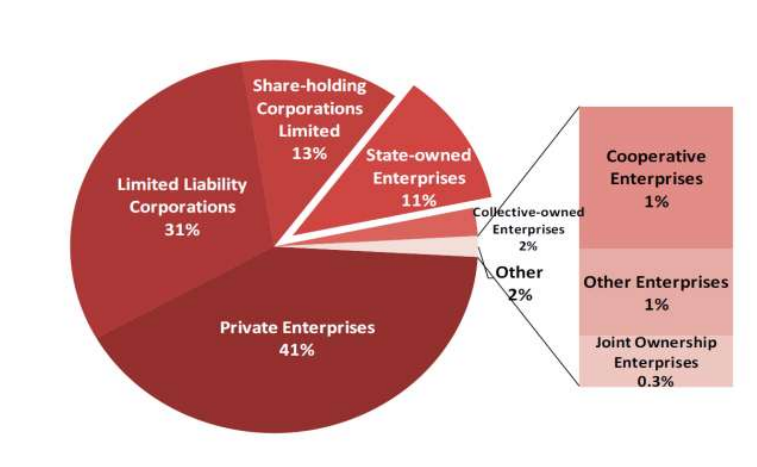

Innovative reform ideas and practices since the 1980s have been shaped by China’s unique development experience. After more than twenty years of economic reforms, China became one of the world’s largest economic sector. It is during this time when SOE reforms have consistently been a main part of the government’s agenda for economic reforms (Grimsditch, 2015). The main goal of SOE reform was to maintain their performance and make them more competitive within an increasingly open economy. These reforms have been implemented through the development of new forms of ownership such as stockholding, while creating a variety of innovative corporate governance mechanisms (Song 2016) [see figure 1 below].

Figure 1: Industrial Output by Ownership (Jefferson, 2016)

Competition and Entrance of Enterprises

Between 1978 and 1995, the level of confirmed industrial entities increased substantially from 349,300 to about 10.02 million, the highest figure in the post-reform era. In 1978, there were about 83,710 SOE firms in China, amounting to 78 percent of the country’s gross industrial production; the 264,700 joint companies made up the rest of the economy (Jefferson, 2016). The number of state-owned firms had increased to 102,100 in 1994, the proportion of groups, including townships and rural enterprises, had increased to 1.85 million, and the number of self-owned and the rest of the firms had increased to over 800 million (Jefferson, 2016). The proportion of total production for SOEs was 37.3 percent; group companies produced 37.3 percent, while self-owned and the other enterprises contributed the remaining 25 percent, led by the self-owned type described as businesses with eight or less staff (Jefferson, 2016).

This tremendous influx of newcomers was matched by an increasing economic liberalization of China’s domestic market as the ‘dual track system’ took shape. The reform of foreign trade and investment intensified marketization and competitiveness even more, with China’s trade ratio rising from 13 percent in 1980 to 38 percent in 1995. Furthermore, rivalry drove SOE change during this early period by creating the quest for recent technological advancements and leadership a need for survival (Jefferson and Rawski, 1994a; 1994b). In the absence of reforms, new firms entering the market and increased competition decreased SOE market share, pushing their more qualified and driven personnel to go to non-state firms. Regulatory bodies were encouraged to implement management reforms as a result of increased competition and the loss of revenue. Reforms aimed at incentivizing managers through cash rewards and enhanced autonomy are effective (Groves et al., 1994). By 1995, winners and losers had emerged among the groups of SOEs, proving the potential of the reform to enhance management motivations to improve the productivity and competitiveness of state-owned businesses (Jefferson, 2016).

Retaining The Major Enterprises While Releasing the Small Ones

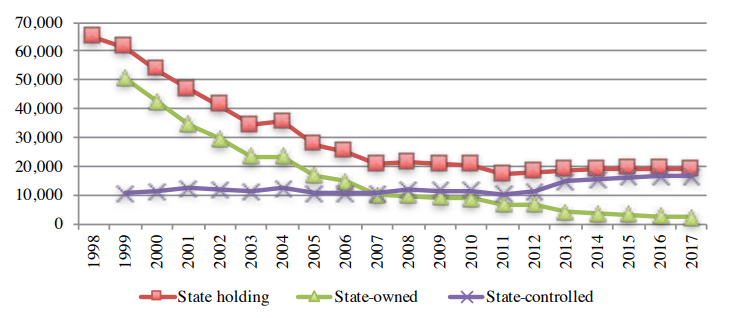

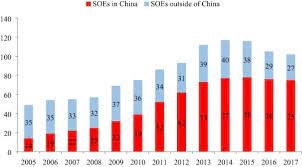

During 1995, China embarked on two major reforms, partly spurred by a desire to prepare for participation in the World Trade Organization. The first was “xiagang,” or worker furlough, which resulted in a large number of layoffs and a reduction in the size of the SOE staff (Hsieh & Song, 2015). From 1995 to 2001, when China entered the World Trade Organization, the number of people employed in the urban regions decreased by 36 million. The second step was the “jueda fang xiao” plan, where the State government approved a strategy to keep dominant SOEs while allowing the preponderance of smaller SOEs to be transferred outside the state sector (Hsieh & Song, 2015). The State Council adopted a massive acquisition from the national government to the municipal level in 1997 to accelerate non-state ownership transitions. From 60,000 in 1999 to 15,000 in 20124, the percentage of above-scale state-owned and state-controlled companies had decreased (Song 2018) [see figure 2].

Figure 2: Number of state-holding enterprises, 1998–2017 (Song, 2018)

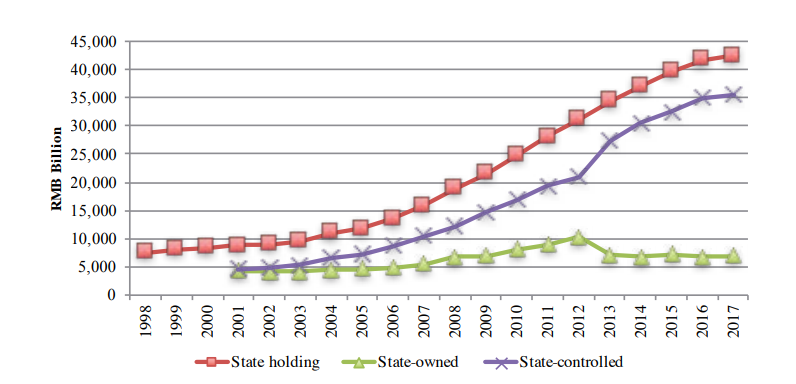

Significant numbers of former SOEs have been sold or restructured as a part of the ‘retaining the major enterprises while releasing the small ones’ policy effort. While most minor SOEs were fully made private, with control passed to managers, employees, or angel investors, varieties of mixed ownership emerged among the bigger SOEs, with the state maintaining dominant control and ownership. During 1995 and 2005, over 90,000 enterprises with 11.5 trillion RMB in resources were privatized, accounting for about 33 percent of China’s SOE firms and public assets and putting China’s privatization ahead in history of mankind (Garnaut, Song & Yao, 2006) [see figure 3].

Figure 3: State-owned and state-controlled companies’ asset size (Song, 2018)

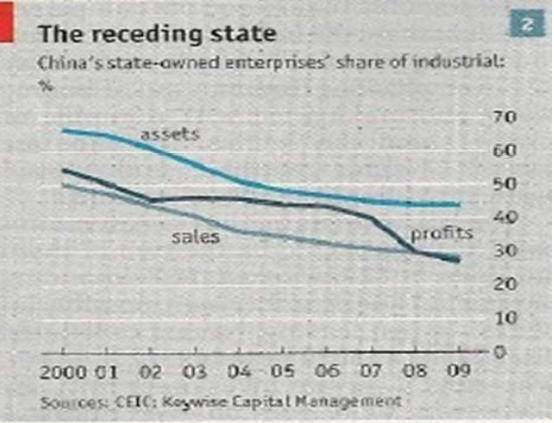

During the second reform period, there was an increase in mergers and acquisitions. Creating a economy for China’s SOE firms that results in the handover of state-owned resources which follows the formulation and deployment of laws, regulatory requirements, and provisions to specify the rights of ownership of state-owned resources and facilitate their deal and transaction between state authorities and private parties in China’s developing markets for enterprise asset sales, mergers, and acquisitions (Jefferson & Rawski, 2002) [See Figure 4 below].

Figure 4: Shares of state-owned and controlled industries have changed (Jefferson, 2016)

The diversification of ownership both within and outside the state system has been a fundamental component of China’s industrial reform initiative over the last 30 years. This has involved the joint entrance of non-state capital into formerly solely state-owned firms and the transfer of state assets to construct resources in non-state businesses (Lam & Schipke, 2017). As an outcome, the traditional National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) criteria of state-owned, state-controlled, share investors, and corporate and international investors are frequently a combination of ownership of asset, implying a very distinct possession and system of governance than the official ownership brand disclosed by the NBS (Lin et al 2020) [see figure 1]. As a result, one driver of SOE productivity has been the ability of the local and foreign investment to gain a presence within the state sector’s borders [see figure 5]. Another example is the exit of particularly inefficient SOEs. Hsieh and Song (2015) use extensive firm-level data showing that state-owned businesses that closed between 1998 and 2007 were smaller and had the lower workforce and resource performance than remaining SOEs. The authors suggest that the shutdown of less competitive SOEs led to state-owned businesses’ worker productivity close to that of private firms between 1998 and 2007. They predict that state-sector reforms accounted for 24 f of China’s overall TFP growth during this period (Song, 2018).

Figure 5: State-owned enterprises in China (Lin et al.,2020)

Re-structuring China’s Remaining State-Owned Enterprises

One significant feature of the research on China’s latest efforts to revise its SOE firms is that a huge percentage of the information and evaluation comes from headlines periodicals such as The Wall Street Journal, the Economist, the Financial Times, and Forbes; as well as news and insights from financial companies and public policy centers (Lin 2021). Several factors are thought to have contributed to this transition. First, the SOE reform narrative is progressively becoming one of a limited and sizable proportion of very conspicuous businesses for which documentation is more easily accessible, given the diminishing proportion of SOEs and the idea that there are 90 percent of the total assets are in the 98 entities of the Forbes Global 500 (Garnaut, Song, & Yao, 2006). Secondly, the majority of the big SOEs are either officially disclosed or are expected to be in line for public auctions and other types of economic interactions with the foreign states in the near future. The world’s economic sector is keen to acquire accurate data and insights pertaining to China’s reform breakthroughs, given the size of the assets represented and the possibility for large commercial deals. The fact that China’s state-owned entities have progressed into a field with such emphasis and monetary interest speaks volumes about the scope of China’s state-owned firms restructure over the last 30 years and the anticipation for significant ongoing transformation and marketing advantage for the surviving SOE firms (Sheng, Hong & Zhao, 2013).

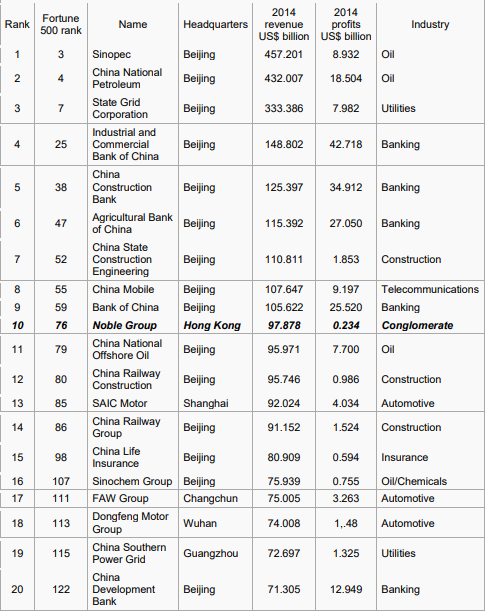

China’s major state-owned and state-controlled companies have undergone a significant transformation on two fronts. The first is their concentration into a small number of conglomerates (about 110). As seen in Table 1, 19 of China’s top twenty enterprises are state-owned and state-controlled, with state-controlled being openly traded on foreign stock exchanges. 98 of the Fortune Global 500’s Chinese businesses are in China, as well as headquarters in Hong Kong. China is only at second position after the United States, with 128 enterprises on the list. When evaluating these 2015 data to previous years, China’s economy appears to be even more impressive. In 2010, China had 46 enterprises on the list, compared to only 10 in 2000. In contrast, the United States has been trending in the opposite direction. 139 U.S. corporations formed the list in 2010, compared to 179 in 2000. The leading 12 Chinese corporations are entirely state-owned, with only 22 private companies among 98 (Jefferson, 2016).

Table 1: Fortune has ranked the top Chinese firms (non-state owned in bold italics) (Jefferson, 2016)

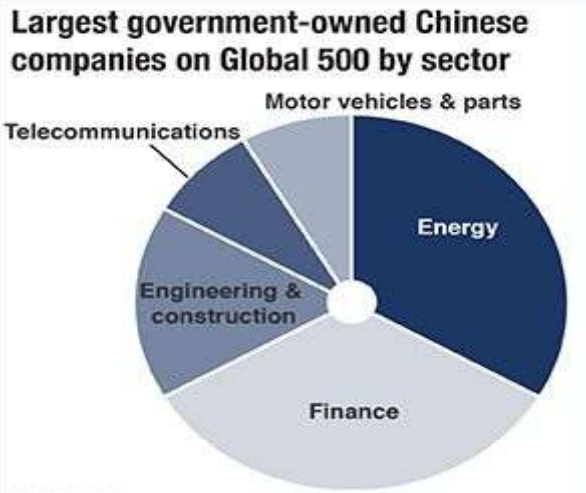

The second existing reform, which is linked to the first, is the growing specialization of SOE assets and commercial activity in a small number of industries that are most directly related to SASAC’s Section 2 public and corporate responsibility aims (Guluzade, 2020). As illustrated in figure 6, nearly one-third of China’s major enterprises’ government-owned and governed resources are in the oil and gas sector, another one-third in the banking sector, and the rest is widely split over telecommunications, engineering and construction and motor vehicles sectors (Jefferson, 2016).

Figure 6: China’s Biggest Public Companies’ Primary Areas of the economy (Jefferson, 2016)

As indicated in [Table 1], the main Chinese SOEs include banks and oil corporations regulated by SASAC, which chooses CEOs and determines major investment decisions (Guluzade, 2020). Even though SOE operation is concentrated in 98 organizations, SOEs remain to permeate the China’s economy, spreading far beyond the industrial sector. The implications of SOEs on private industry has become more detrimental as the growth suffers (Huang and Jing, 2019). Amidst the reshaping of China’s state-owned market in the last decade, Huang and Jing (2019) believes that Most of China’s institutional disruptions, both economical or otherwise, are caused by the SOEs’ prevailing roles.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in order for the state-owned enterprise to be successful as seen in china, the regime must establish a deregulation and Competition, monitor Competition and entrance of firms, Retain the major enterprises while releasing the small ones, and Restructure the Remaining State-Owned Enterprises. All must be done with the objective of continuing to modernize China’s economic system. As a result of the gradual marketization of China’s economy, the state-owned sector has been compelled to undergo a process of modernization through industrialization and international integration. This is especially true in those industries that are deemed “strategically important,” including the petroleum, defense, and power sectors. Nonetheless, for the time being, it appears that China’s SOEs will remain a major part of her economy moving forward. This has contributed to the state-owned enterprises’ prevalence in the realm of international politics and their standing as a major economic and political force in China.

References

Garnaut, R., Song, L., & Yao, Y. (2006). Impact and significance of state-owned enterprise restructuring in China. The China Journal, (55), 35-63.

Grimsditch, M. (2015). The role and characteristics of Chinese state-owned and private enterprises in overseas investments. Friends of the Earth United States, 11.

Groves, Theodore, Hong Yongmiao, McMillan, John, and Naughton, Barry, (1994). “Autonomy and Incentives in Chinese State Enterprise,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 109(1), 183-209

Guluzade, A. (2020). How reform has made China’s state-owned enterprises stronger. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/how-reform-has-made-chinas-state-owned-enterprises-stronger/ Retrieved Feb 9, 2022

Hsieh, C. T., & Song, Z. M. (2015). Grasp the large, let go of the small: The transformation of the state sector in China (No. w21006). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Huang, Q. and Jing, Y. (2019). State-owned enterprises in China: their reform process, performance efficiency and future road, China Political Economy, 2(2), 201-214. https://doi.org/10.1108/CPE-10-2019-0022

Jefferson, G. (2016). State-owned enterprise in China: Reform, performance, and prospects (No. 109).

Jefferson, G.H. and Rawski T.R. (1994a). “Enterprise Reform in Chinese Industry,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 8(2), 47-70.

Jefferson, G.H. and Rawski, T.G. (1994b) “How Industrial Reform Worked in China: The Role of Innovation, Competition and Property Rights.” In Proceedings of the World Bank Annual Conference on Development Economics, 129-156.

Jefferson, G. H., & Rawski, T. G. (2002). China’s emerging market for property rights: Theoretical and empirical perspectives 1. Economics of Transition, 10(3), 585-617.

Lam, W. R., & Schipke, A. (2017). ” Chapter 11. State-Owned Enterprise Reform”. In Modernizing China. USA: International Monetary Fund. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/books/071/23209-9781513539942-en/ch11.xml

Lin, K. J., Lu, X., Zhang, J., & Zheng, Y. (2020). State-owned enterprises in China: A review of 40 years of research and practice. China Journal of Accounting Research, 13(1), 31-55.

Lin, J. Y. (2021). State-owned enterprise reform in China: the new structural economics perspective. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 58, 106-111.

Putterman, L. and Xiao-Yuan, D. (2000). China’s State-Owned Enterprises: Their Role, Job Creation, and Efficiency in Long-Term Perspective. Modern China 26 (4), 403–47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/189426.

Sheng, H., Hong, S., & Zhao, N. (2013). China’s state-owned enterprises: Nature, performance and reform (Vol. 1). World Scientific.

Song, L. (2018). 19. State-owned enterprise reform in China: Past, present and prospects. China’s 40 Years of Reform and Development, 345.

write

write