Coronavirus (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus (World Health Organization, 2020). It was identified late in December 2019. Coronavirus resulted in symptoms like the common cold, loss of appetite, and shortness of breath, causing many deaths, especially those in the older age brackets. It resulted in the closure of churches, schools, and countries, so people could not travel or continue their daily activities as usual. People wore masks, and public gatherings were prohibited as a protection measure. Hygiene was observed keenly by washing hands thoroughly. During the pandemic, almost all countries had their most significant economic downturn, with estimates by the International Monetary Fund (I.M.F.) showing that between 2019 and the pre-pandemic period, the median global G.D.P. dropped by 3.9% from 2019 to 2020 and by 1.9% in P.E.P.F.A.R. countries (Oum et al., 2022). This essay elaborates and dwells on how COVID-19 impacted most economic activities in various countries, specifically, how Covid-19 affected financial and stock markets, employment, tourism and hospitality sector, health sector, technology and communications, supply chain management, consumer spending, and business investments due to market uncertainty.

COVID-19 resulted in a drastic plunge in the primary stock market. A significant percentage of stock market value was lost. The global stock markets incurred substantial losses, and International Financial Institutions failed to meet their projected growth levels (Jabeen et al., 2022). Increased cases/deaths created more volatility and jump while decreasing the returns for stock market investors. Cruise Ship Operators, Carnival Corporation, and Norwegian Cruises Holdings were the most affected companies). COVID-19’s stoppage of the global tourism industry during the lockdown in countries, counties, and states led to a collapse of demand for energy stocks and products like fuel, resulting in huge losses. A global crisis in stock markets resulted in a slumping of median world G.D.P., hence the global economy’s collapse.

There was a decrease and plummet in employment due to COVID-19. Contracts were not renewed for many people; hence, most individuals lost their jobs. Old hiring practices were disrupted, and few organisations were recruiting during this period. In the United Kingdom, 825 000 workers left the workforce between January-March 2019 and October-December (Powell et al., 2022). There was a significant drop during the same period; unemployment rose by more than 400,000 people, and those who were not economically active topped at around 327,000 (Powell et al., 2022). This period saw record levels of redundancies, contributing to a massive impact on the employment landscape. More so, working hours in the U.K. reached their lowest level since 1994, thus illustrating how hard it was for the labour market to cope during this period (Powell et al., 2022). Economic Policy Institute estimates that three million jobs were lost in the United States alone and almost twenty-five million jobs worldwide. The people who suffered the most were those operating at a physical workplace and providing essential goods or services, like frontline workers, since they had a high risk of contracting infections and losing their livelihoods (O.E.C.D., 2021). Companies could not hire since the number of customers decreased as people switched to online shopping rather than physical shopping, and there was a reduction in investment in imports because countries put up travel restrictions, leading to reduced income for companies. The slowdown of the global economy was due to a decrease in G.D.P. or, more particularly, a result of a decline in consumer spending. COVID-19 led to the worst recession in the global economy. COVID-19 triggered a global recession in most countries starting in February 2020 due to the induced market volatility and lockdowns. Pandemic measures of lockdown and other precautions undertaken led to a massive crisis in the global economy.

COVID-19 led to reduced consumer spending because of the reduced purchasing power caused by increasing unemployment and layoffs. Every purchase made by a consumer helps in maintaining the business. COVID-19 caused citizens to lose jobs. Little disposable income meant that they spent less on non-essential goods. The pandemic changed spending habits due to debts left behind (Gupta et al., 2020). International travel was banned in most countries, and movement was controlled. Therefore, strict restrictions on public movement caused isolation, changing most consumers’ demand patterns. For instance, travel bans forced people to cancel their flight schedules, making most airlines like Lufthansa, Virgin Atlantic and Emirates lose money. Many people shied away from public places due to fear. As such, areas including restaurants suffered the most. Commodities like cars, clothes and even schools faced reduced incomes because people had to work from home. People have developed technology that improves remote working and e-commerce, which reduces interaction with the outside world. Consumers were unwilling to buy, businesses became bankrupt, and employees were laid off to remain sustainable. Governments also suffered losses on the amount of taxes paid, meaning that their budgets for projects which could help improve their economies were limited. The COVID-19 pandemic led to more unemployment since organisations had to let go of workers for them to survive. It was difficult for people searching for jobs as fewer firms were hiring. Many people also lost their jobs as most closed down their enterprises. Reduced purchasing power means business losses, which calls for layoffs as a cost-cutting strategy in human resources costs (Parash, 2015). An employee is one of the most important inputs into any business, but COVID-19 changed the nature of work for employees. Stress related to the effects of the pandemic remained prevalent across the globe and caused negative experiences for employees. The impact of stress in the human task force left businesses dealing with reduced mental abilities within their workforces, absenteeism and weakened motivation at the workplace. Poor psychological and physical health of employees will result in low productivity, which means that the economy will not be operating at its full potential. Household consumption of goods and services could significantly influence the economy.

Economic activities were reduced as the demand, supply, trade, and finance of goods and services suffered disturbances greatly. Individuals’ per capita income was reduced, causing severe poverty. Countries that depended on global trade, tourism, commodities exports and external financing were hardest hit by the recession (Barua, 2020). There were disturbances, and these varied differently in different regions. Interruptions in access to primary health care and schooling affected human capital development. COVID-19 reduced overall economic performance since a country’s economic well-being is determined by the overall supply of services and products created within a specified period. The pandemic affected every aspect of production, sales, income, and employment worldwide. Low production levels caused many businesses to stagnate, which affected the national income, and therefore, poverty increased due to the loss of sources of revenue. Most countries witnessed a decrease in foreign investors, which can harm an economy’s G.D.P. growth. Even before the Coronavirus, developing economies had problems, and the COVID-19 pandemic worsened matters.

COVID-19 increased the use of digital technologies for communicating, social interaction, and working from home. People’s preferences shifted away from traditional shopping to online purchases. Organisations have implemented digital technologies that have led to digitising customer interactions and supply chains and increased sharing of digitally enabled products. With multiple lockdown measures, online shopping facilitated the everyday functioning of businesses that would have otherwise taken much time. As more consumers choose to buy their products online, economic growth improves, contributing to the overall recovery of the global economy.

COVID-19 negatively impacted the supply network and interrupted the production process on a global scale (Choudhury, 2020). Research conducted by the Institute of Supply Management discovered that there were companies whose supply chains had been disrupted as they did not receive goods at the right time because they found it difficult to get reliable information from China. Dun & Bradstreet (2020) said the pandemic also impacted large supply companies. Furthermore, people in the global supply chain have witnessed lower income and job losses due to COVID-19 (Magableh, 2021). People all over the world in organisations have been closing down shops, decreasing orders and delaying production. Sectors like garments, mining, jewellery and automobiles are the sufferers because their employees have been less protected than any other sector in underdeveloped countries since they have a high risk of contracting COVID-19 (Magableh, 2021). Supply chain disruptions due to COVID-19 dragged business activities and trade at the global level, thus contributing to the slowdown of the world economy since the government had to place restrictions on movement and impose lockdowns. It took a lot of work for manufacturers of goods distributed along the supply chains to reach vendors outside the national borders. For instance, the closure of pharmaceutical industries in China led to a drug shortage for international health facilities. The pandemic also impacted the movement of goods from wholesalers, distributors and retailers, which slowed down lead time for expected deliveries. The supply chain cycle slowed down, and in some cases, companies were unsure about receiving deliveries. For instance, the Chinese export industry became limited due to the closures of the airlines and seaports. Any organisation that had paid for China’s orders during this period incurred a delay and struggled to predict their supply chain cycle. The global chain was also affected by price fluctuations due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In production companies, prices for raw products increased because there was a shortage of raw materials.

Uncertainty in the market led to reduced business investments. Investors panicked about the safety of their investments following disruptions caused by COVID-19. The global and local markets seemed too risky, so business people became uncertain about the future conditions of the economic environment. Slow economic growth was attributed to low trust in the economies. Reduction in trade flow resulted in entrepreneurs deferring investment projects. In organisations, managers restricted the purchasing of commodities as there was a need to save every cent. Also, the number of newly hired staff decreased. The public panicked and began to fear for the supply of essential goods required to take them through self-isolation. Financial institutions also reduced their lending because they could not be sure the money would be repaid, and businesses found it hard to borrow funds or loans (Kliesen, 2013). The spread of the COVID-19 pandemic led to adverse effects that created uncertainty, which is detrimental to a country’s economy’s growth.

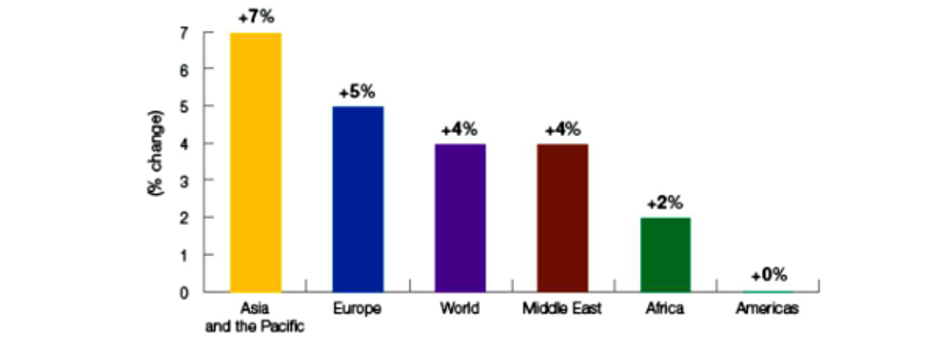

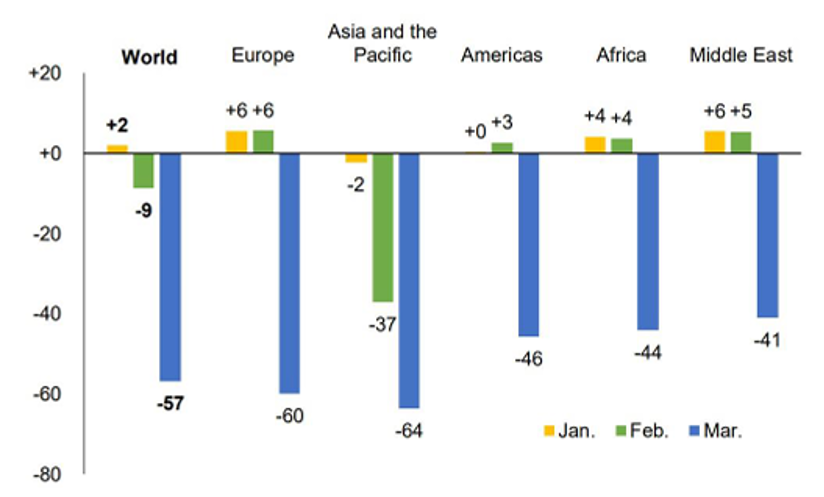

COVID-19 caused the shutdown of the travel and hospitality industry. The hospitality industry employs many people who are highly exposed to guests from across the country and outside, exposing them to high risks of contracting Coronavirus. There were few customers at hotels and restaurants. People lost their jobs as employees were laid off massively in the hospitality industry. According to the United Nations Trade and Development Body, COVID-19 halted tourism, which saw more than four trillion dollars lost in the world economy (Fabien, 2022). The closure of the tourism and hospitality sector resulted in low revenues and a drop in the global G.D.P. while the world economy severely decreased. In general, the travel and tourism business has been hit hard, although not uniformly, with some places being hit harder than others. Because the virus came from Asia, this region was predicted to have the most significant decrease in worldwide tourism revenue, and among Asian countries, China had one of the most significant proportions of loss. Some famous tourist locations in Asia, like Indonesia and Vietnam, have recorded double-digit tourist decreases. 65% of travel plans in the Asia-Pacific region were affected after the COVID-19 virus started spreading around South Korea. Depending on performance, travel and tourism are considered two of the world’s most important industries for global G.D.P. Tourism contributed ten per cent of the world’s G.D.P. in 2019, generating US$8.9 trillion of the global economic output and providing employment to around 330 million people. Other sectors of the industry, like catering and hotels, were also affected by this epidemic. Production of all industries that generate revenue from supply and demand has been affected by the pandemic. In the view of the World Bank Group, labour and capital were underutilised in industries reliant on manual labour; trade costs negatively affected businesses that traded goods with other countries, while high tourism taxes coupled with flight cancellations across most parts of the world affected individuals involved with or dependent on services provided by companies related to leisure itineraries. From a global viewpoint, the World Bank Group forecast a 9.3% drop in global output, an 8.8% drop in tourism services, and a 3% drop in agricultural and manufacturing production (Maliszewska et al., 2020).

Due to consumer buying during COVID-19, the food industry has faced much pressure, especially regarding delivery and sales. The food supply chain impacted farmers, distributors, consumers and businesses involved in labour-intensive food processing. Many factories limited, stopped, or even paused their production due to the COVID-19 workers who were unwilling to go to work and worried that they might get sick at their workplace, primarily in the meat processing food industries during that epidemic (Aday & Aday, 2020). Due to this, there was rising apprehension that food could be scarce, and panic buying led to more than £1 billion worth of food hoarded in households across the U.K. (Hailu, 2020). Online food delivery has also been affected by the increasing demand for food goods. Moreover, food banks are impacted by people shopping in panic and hoarding foods due to decreased donations. While the government assured how businesses adapted, significant changes were made, including limiting how many products consumers could buy.

Figure 1: International tourism receipts by regions, Source: W.T.T.C. (2019).

Figure 2: International tourist arrivals, Jan, Feb, March 2020 (% change), Source: W.T.O. (2020).

Nevertheless, there has been significant growth in the healthcare industry due to Coronavirus. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the depth of vulnerabilities in health systems and how it can have dire effects on health, economic development progress, faith in governments, and social harmony (O.E.C.D., 2021). Keeping and controlling this virus’s spread of infection rates is still critical. However, the same is true of strengthening the ability of health systems to respond quickly and capably. This includes the COVID-19 vaccination program. Vaccine campaigns are being rolled out in many countries after lightning-speed development and testing. However, this leaves questions in production, delivery and equitable distribution for low-income and middle countries. The COVID-19 pandemic enormously affected societies and health systems in and outside the O.E.C.D. member countries. Health systems were not resilient enough. Resilient health systems are usually prepared for shocks like pandemics, economic crises, or the impacts of climate change (Morgan & James, 2023).

In conclusion, the shift of the world offered a change in operations even after the containment of pandemics. Several governments worldwide have created recovery initiatives to help their economies recover from COVID-19. Giving loans to S.M.E.S., tax holidays, business incentives, restructuring loans and offering support to citizens are among the recovery initiatives governments should consider. Coronavirus has had dire consequences, such as dislocation in the global management of supply chains, changing consumer spending habits and uncertainty surrounding conditions on external markets, and shutting down businesses. Thus, most countries encountered a decrease in G.D.P. Governments are supposed to seek sustainable economic actions that would benefit them in the long run. Policymakers should develop new plans to respond to the pandemic and mitigate its negative consequences by creating jobs and helping businesses. Coronavirus started as a health disaster, becoming an economic crisis due to severe social isolation and country-wide lockdown. The world’s most influential players, such as the United Nations, WHO and the Red Cross, can cooperate to alleviate the problem. A global community effort also has to be orchestrated. In the fight against anti-virus, technology support is crucial by creating a multi-policy approach covering climate change, economies, the public health sector and population risks. Creating a new type of social contract between individuals and society is essential. 2020 has been unpredictable for organisations as they never knew the COVID-19 was coming. Governments had not prepared businesses for a pandemic, and the impact of social distancing was devastating to business organisations. Customers just vanished, and some became ill. Besides that, trade was dropping with tourism, and there was limited capital flow – sales were reducing while financial conditions became flexible, and debts affected businesses badly. Businesses owing debts or having stunted working capital had to shut down due to pressure in operations caused by the challenges of this pandemic. Firms that deal with personal relationships, such as entertainment and travelling, had to close due to social distancing. Trade restrictions, dwindling customer demand, and interruptions in the supply chain severely affected exporting businesses.

References

Aday S, Aday MS. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on the food supply chain. Food Qual Saf. 4:167–80. doi: 10.1093/fqsafe/fyaa024

Barua, S. (2020). Understanding Coronanomics: The economic implications of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Available at SSRN 3566477.

Gupta, M., Abdelmaksoud, A., Jafferany, M., Lotti, T., Sadoughifar, R., & Goldust, M. (2020). COVID-19 and economy. Dermatologic therapy, 33(4), e13329-e13329.

Hailu G. (2020). Economic thoughts on COVID-19 for Canadian food processors. doi: 10.1111/cjag.12241

Jabeen, S., Farhan, M., Zaka, M. A., Fiaz, M., & Farasat, M. (2022). COVID and world stock markets: A comprehensive discussion. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 763346.

Kliesen, K. L. (2013). Uncertainty and the economy. The Regional Economist, Apr. https://ideas.repec.org/a/fip/fedlre/y2013iaprx8.html

Magableh, G. M. (2021). Supply chains and the COVID‐19 pandemic: A comprehensive framework. European Management Review, 18(3), 363-382.

Maliszewska, M., Mattoo, A., & Van Der Mensbrugghe, D. (2020). The potential impact of COVID-19 on G.D.P. and trade: A preliminary assessment. World Bank policy research working paper, (9211).

McQuaid, R. W., & Lindsay, C. (2013). The concept of employability. In Employability and Local Labour Markets (pp. 6-28). Routledge.

Morgan, D., & James, C. (2023). Investing in health system resilience.

O.E.C.D. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on health and health systems – O.E.C.D. Www.oecd.org. https://www.oecd.org/health/covid-19.htm

O.E.C.D. (2022, March 17). The unequal impact of COVID-19: A spotlight on frontline workers, migrants and racial/ethnic minorities. O.E.C.D.

Oum, S., Kates, J., & Wexler, A. (2022, February 7). Economic impact of COVID-19 on P.E.P.F.A.R. countries. KFF. https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/issue-brief/economic-impact-of-covid-19-on-pepfar-countries/

The World Bank. (2020, June 8). The global economic outlook during the COVID-19 pandemic: A changed world. The World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/06/08/the-global-economic-outlook-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-a-changed-world

Upreti, P. (2015). Factors affecting economic growth in developing countries. Major Themes in Economics, 17(1), 37-54.

World Health Organization. (2020, January 10). Coronavirus. Who.int; World Health Organization: WHO. https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus

World Tourism Organisation (W.T.O.), (2020). Available online: https://www.unwto.org/impactassessment-of-the-covid-19-outbreak-on-international-tourism

World Travel & Tourism Council (W.T.T.C.), (2019). Economic Impact Reports. Available online: https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact

write

write