The Russia-Ukraine war offers entrepreneurs, company leaders, and policymakers a new challenge regarding its economic impact. Covid-19 had already disrupted the global economy two years before the war, and economies, especially in emerging countries, were beginning to recover. With the war causing supply and price shocks, most countries having close trade ties with Russia or Ukraine had their economic gains after Covid-19 was erased. Although production and consumption were interrupted, war can be the beginning of self-sufficiency in most countries through creating new reliable supply chains, especially in the case of the E.U., which relies heavily on Russian oil, even though the latter is under global red light. Pressure on the E.U. by the West to cut Russian trade ties is a challenge to most E.U. countries as that would mean high energy costs, among other items that would be in demand. The E.U. is already being hit with high energy costs and a shortage of various metal supplies from Russia (Prohorovs, 2022). One of the global oil and gas analytic agencies Rystad Energy, states that the global LNG demand for 2022 is 436 million tonnes, and the supply is currently at 410 million tonnes. A country like Austria, which gets 80% of its gas from Russia, risks a severe economic recession if it were to cut ties with Russia. Rystad Energy forecasts that it cannot cover all the demand; gas will rise from 1000 to 3500 cubic metres in the upcoming year (Prohorovs, 2022).

The supply shock caused by the war raised oil and food prices, reducing economic growth and increasing inflation. Black-Rock investment company forecasts that the E.U. countries will lose at least 9% of their GDP due to the war. One of the strongest economies in Europe, Germany, was also affected by the war and energy prices as the Industrial Production Price Growth index March 2022 was 30.9% and April 33.5% (Prohorovs, 2022). The war subsequently slowed down labour markets, especially in neighbouring countries; other countries, such as Moldova economies, were hit by migration and sanctions, which disrupted resource channels and disruption of supply chains. Central Bank of Ireland economist Reamann Lydan states that 21 countries in Europe experienced slow growth immediately after the war commenced. Inflation hit employment the hardest as Russian imports reduced and energy-dependent sectors slowed down (Prohorovs, 2022). Therefore, the inflation impact will depend on the Countries’ connection to Russia and Ukraine and their economic capability. Generally, the inflation triggered by the war will continue to cause economic uncertainty, proving a difficult task for Central Banks.

The Russian-Ukraine war is continuing to push inflation rates through the ceiling. According to researchers, the high inflation rates have hit a two-long decade low as inflation quickly spreads to housing and other sections. These high rates of interest inflation were a possible risk of a permanent change in inflation expectations which would mean a loss of credibility for Central Banks. Henceforth, now more than ever, Central Banks have no wiggle room to get it wrong. The monetary policies they come up with have to be just right while avoiding disruptive economic adjustments in the long run. The Federal Reserve, Bank of England, and Bank of Canada have already continued to raise interest. Also, the European Central Bank (ECB) increased point rates by at least half while adopting the Transmission Protective Investment. With these monetary policies now in the spotlight more than ever, it is a chance to prove how strong they are, especially when not backed by fiscal policies to control inflation. However, the federal government made projections that show positive long-term signs. The measures adopted by Central Banks would lead to an increment of real interest on government bonds and negative short-term rates. However, the model would readjust, and in 10 years, the real rate forward curve covers positive inflation rates which an expansion range of ½% to 1%. According to (cite IMF), Central Banks should approach the application of countermeasures slowly for a more permanent solution with little economic backlash. However, a stern, precise anchor on inflation would later be set up to help restore policy credibility as the financial markets and the economy readjusts. However, a fast policy rate would lead to a decline in equity, credit risk assets, and market assets. The financial market would be unstable, while emerging markets would suffer the brunt of this approach. The Central Banks, at all costs, cannot lose credibility by allowing the expectation of inflation to soar. In consumer studies in places like the U.S. and Germany, it is already evident that people are aware of the inflation rates and believe that the expected inflation rates will continue to rise even in 2023 (Adrian et al., 2022).

Kilian and Zhou (2022) subsequently set out to investigate how oil prices affect inflation and the longevity of the impact on relevant economies. The researchers adopted a vector autoregressive model and used the Michigan Survey Consumer data to explore the relationship between oil prices and inflation and its expectations. However, the study uses gasoline prices as opposed to crude oil to get the most impact of inflation in households as per the I.S. curve. With the war having a massive impact on energy prices in Europe, Kilian and Zhou (2022) VAR model is a perfect natural framework to apply to the high energy prices as a result of sanctions on Russia and military spillovers; and to investigate how these energy prices affect inflation and expectation inflation targets over five years. The choice to use the Covid-19 VAR framework is because of the pandemic and war crisis similarity based on the underlying elements of energy prices and inflation.

Economists have often accused Central Banks of placing all or most of their economic securities on the cushion of monetary policy and, to some extent, disregarding fiscal policies. Monetary policies rely heavily on adjusting interest rates, which have been used for decades to solve economic issues and produce little to no consequences. The dominance of monetary policies is backed up by huge financial houses such as the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve.

However, Rochon (2022) states that he is disillusioned with how financial institutions use monetary policies by fine-tuning interest rates and setting an inflation ‘target’ that would prompt action if ever surpassed. The researcher implies that Central Banks should not treat changes in interest rates or inflation as a monetary phenomenon but rather as a monetary policy phenomenon. Rochon (2022) is also pessimistic about how Central Banks can build stable inflation around an arbitrary inflation target. The author claims these new Keynesian models have little empirical support, yet professionals use them with the idea of the linear relationship between interest output and inflation. The primary relationship in a highly complex economy has sometimes proved ineffective, as inflation shows that it is flexible to easing monetary policy. Monetary policies are asymmetric, and hence easy to make a mistake by raising interests too much or too close to the neutral line; this would mean more inflation or slow economic growth, respectively. With monetary policies covering only one pillar of controlling inflation, fiscal policies cover a multitude of other factors, and predicting or controlling inflation via monetary policies can be ineffective as inflation is in a dynamic economy. Additionally, these consensus models need to account for the output gap, which is why Central Banks are always busy using monetary policies to counter the ever-unstable inflation in small variations. Rochon (2022) states that the set target of 2% is a fictitious variable that cannot be calculated precisely. Meanwhile, the I.S. curve depends on the assumption that interest rates affect output and consumption in households and business investments. However, it is hard to find empirical evidence that shows household consumption is affected by interest rates. The same case goes for the Philips curve in which Central Banks do not consider that labour markets have little to no effects on inflation.

References to previous research on the topic

Between 2015 and 2019, Central European banks were preoccupied with raising inflation to at least 2%. During that period, inflation hovered around 1 to 1.5% in the Eurozone. However, in 2022 inflation soared to 9% in the United Kingdom and 7.5% in the Euro region, making Central Banks work around the clock to try and bring it back down (Reis, 2022). However, questions still need to be raised as to how the successful monetary policies that have worked so well for the last two decades suddenly seem to fail.

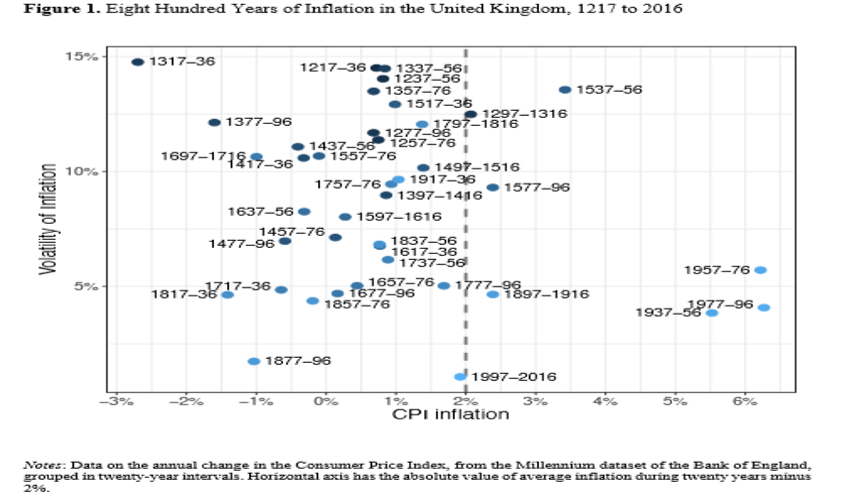

The United Kingdom’s inflation data for over half a millennium records the two decades from 1996 as one of the most stable inflation periods (Graph).

However, before we look at why the Central Banks are having a hard time regulating inflation, one has to wonder what made the last two decades an unprecedented success period in controlling inflation. The independence of Central Banks from the government ministry of finance was a great move to alienate Central Banks from managing public finances and prevent transient simulations of the economy, especially during re-elections. As such short-term economic stipulations often lead to high inflation rates. Also, the obligation of Central Banks to the ministry of finances is to have a required balance that periodically transparently measures its performances. Finally, the final factor or condition uses interest rates as the main monetary policy instrument. The above conditions and guidelines keep Central Banks working independently, easing measures to control inflation.

A few months after the pandemic, the Eurozone and the U.S. economy bounced back strongly, up 14.9% and 17.1% in GDP (Reis, 2022). The unemployment rate in the U.S. also rose by 10%, with economists viewing the fast growth as a force to drive up inflation. However, between 2021 and 2022, there were three sets of shocks, one caused by the Russia-Ukraine war, which drove inflation up because of the Central Bank’s misdiagnoses. By adopting the Philips curve as the only countermeasure, the monetary policies to counter all three shocks did not account for the persistence of inflation. As a result, every time inflation burst through the targets during the shocks, the expectations rose, and the inflation worsened. By treating the concurrent shocks as temporary unrelated changes in the output instead of the persistence of the first inflation shock, the Central Banks inadvertently opened a crack that let inflation skyrocket (Reis, 2022).

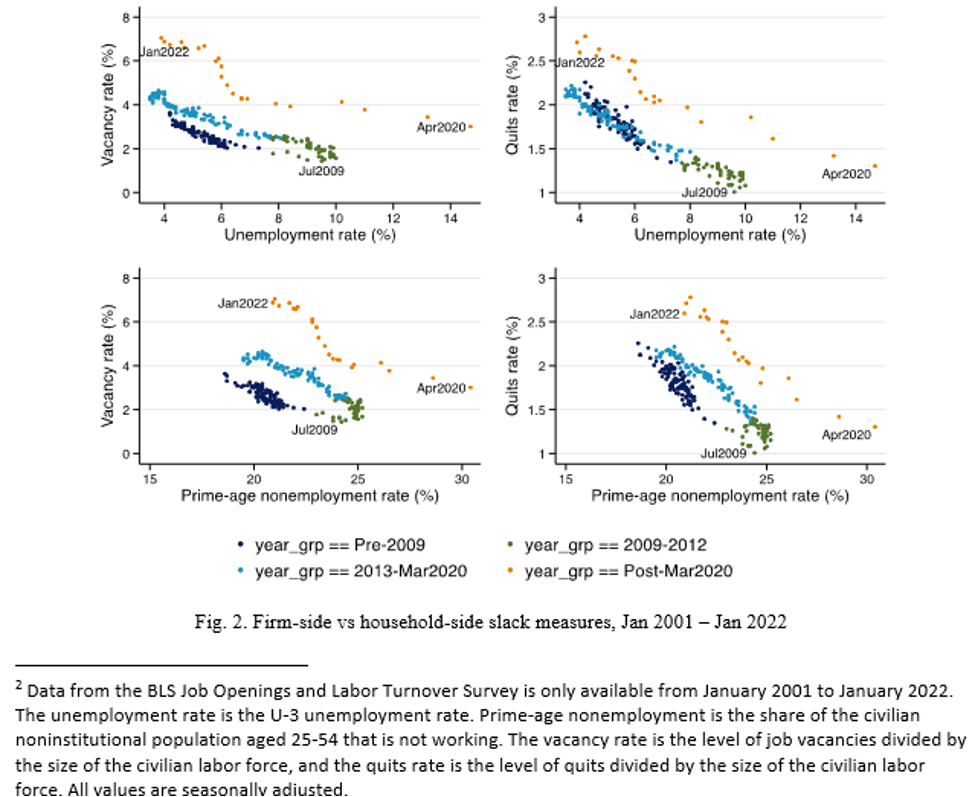

After the pandemic, the labour market quickly loosened up and expanded to mirror the quickly expanding economy. Unemployment rates were hitting new highs as compared to the previous half a decade, and inflation seemed easy to manage by Central Banks. Looking at the Philips curve, inflation and jobless rates seemed healthy. However, rates of vacancies and quitting were skyrocketing, which shows an unconventional relationship with the unemployment rates. As a result, measuring labour market tightness with unemployment rates is raising controversy as to whether it is the right call; or a combination of all critical factors. Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chairman, suggested that a deeper look at employment indicators can be a more accurate way of measuring labour market tightness (Domash & Summers, 2022). Beveridge-type curves show below show a complete outward shift suggesting a sudden increase in the numbers of people quitting and vacancies (graph5)

The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, as of Feb 2022, reported a 6.5% wage inflation which prompted a change of the federal fund rate to 0.25% in March. With the fast-growing economy and high quit and vacancy rates, economic slowdown or recession is the only remedy for inflation. With the vacancy rates affecting wages and labour market tightness, the Fed must engineer various soft-landing mechanisms to prevent a further economic sink (Domash & Summers, 2022).

Deduction

Oil or energy prices, in general, have always been a big player as far as the financial market and economic activities are concerned. Henceforth, energy prices are one of the indicators that undoubtedly have the capability of affecting inflation at global levels. With energy being a main thread holding together manufacturing and production sectors in the economy, its prices, henceforth when undesirable, have a widespread effect on many economic sectors. During the Covid-19 pandemic, labour markets constricted and became extremely tight as most supply chains were internally and externally disrupted or entirely cut. Economic activities slowed down as most nations directed their financial efforts to tackle the pandemic.

Consequently, a shortage of coal and natural gas led to price hikes in energy. As of 2021, energy prices were already soaring as a barrel of oil went for $80 by West Texas Intermediate. High demands for oil merged with low economic growth, low inventory, and inadequate supply from oil-supplying countries meant high inflation was looming. The rising prices meant that high costs would be distributed to gas retail, ultimately reaching consumers via the prices of products and wages (Kilian & Zhou, 2022).

The Philips curve approach is one of the most used economic frameworks, especially for analyzing inflation in labour markets. The approach, however, to make it more efficient, has to incorporate not only monetary policies but fiscal policies as well. Two main focuses of inflation through the approach are to consider and answer the converging point of inflation or the inflation expectation. Another focus is how the changes in inflation will or can cause a permanent effect on inflation rates (Ubide, 2022). Since 2007, the European Central Bank has struggled to raise inflation targets as inflation was very low. However, will inflation be Asymmetric, and monetary policies alone are not enough to control it?

Additionally, targeting inflation rates of 2% means accepting lesser inflation risks. However, lesser inflation risks mean inadvertently accepting high inflation as now the low set target is the highest preparation a particular economy is willing to handle. As a result, the economy’s future growth slows down. When Russia invaded Ukraine, inflation quickly soared as the entire Eurozone was thrust into economic uncertainty. Once oil demand increased, energy prices rose rapidly. Energy prices, widely used products, were wildly demanded, ultimately breaking the previously set inflation records. However, after a few months, the European Central Bank raised interest rates to lower inflation to the set target of 2%. But, Ubide (2022) believes that such quick monetary policy interventions of low risks and fine-tuning inflation to a single convergence target may only sometimes be the right move.

Since the recession during the pandemic, the goal was always to keep inflation its expectation at precise targets through monetary policy manipulation. However, Ubide (2022) states that such a trend of reducing inflation by targets with no mathematical source is subject to various loopholes, especially in a highly diverse economy. Therefore, it is essential to support monetary policies with fiscal policies. One example is the Covid-19 supply shocks that triggered Central Banks and the federal reserve to raise interest rates. At the same time, fiscal policies worked alongside to help stabilize unemployment and stabilize prices. Also, fiscal policies hedged a maximum employment rate which would ultimately integrate with monetary policies to counter neutral levels. The Russian-Ukraine war also exposed the weaknesses of treating inflation as a monetary phenomenon. By only increasing interest rates, the measure did not address income and price surges; consequently, inflation even rose further as monetary policies alone could not anchor against things like supply shocks. However, as Central Banks struggle, as always, to bring inflation rates down to the target, the adoption of a combination of fiscal and monetary policies to address inflation as it is a purely economic phenomenon (Ubide, 2022)

Hypothesis

Hypothesis: Energy prices and monetary policies by the central banks are responsible for the soaring inflation rates after the commencement of the Russian-Ukraine war.

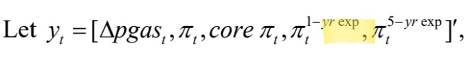

Researchers Kilian and Zhou (2022) embarked on a study to showcase how energy or oil prices affect inflation when they vary. The researchers use gasoline prices as a markup for oil prices to get a broad scope of its effects on households. The two economic experts settled on using a structured vector autoregressive model. Historical data is used in the modelling process to determine how prices sway, affect inflation, and for how long. The methods and approaches Killian and Zhou (2022) use are highly relevant and of interest to macroeconomics. The model takes the form of the equation below.

With the pgas symbol representing gas prices, pie and core pie representing headline inflation and core inflation, respectively. Meanwhile, the pie power is a timeline variable that shows the median of expected inflation from a specific population (Michigan Survey).

After running the autoregressive model, Kilian and Zhou (2022) found out that the nominal price shock of gasoline triggers persistent shocks after the initial one. Most Central Banks did not consider the successive persistence of inflation caused by gas prices. As a result, the losses monetary policies after the Russia-Ukraine did little to prevent inflation.

The model also shows that nominal gasoline prices at the retail level regularly cause a sharp increase in headline inflation. Killian and Zhou (2022) state that considering the impacts of energy prices impacts at lower levels, such as food, instead of measuring the broader effects of inflation at corporate or national levels. The gasoline prices cause an increase in products as well as production processes directly or indirectly. Gasoline prices cause at least 63% and 7% of the variability in the CPI inflation rate and core CPI inflation rate, respectively. Also, variability in expected inflation was 38% and 14% in years one and five, respectively. Therefore, the VAR model clearly links inflation and expected inflation with oil price surges. Henceforth, Killian and Zhou (2022) show that the lack of vigilance on the possible persistence of inflation can ultimately result in a higher inflation rate.

The European Central Bank’s loose monetary policies and pushing fiscal policies to the second seat were essential factors in the inflation after the Russia-Ukraine war. When the West placed sanctions on Russia, the oil and energy prices skyrocketed due to excess demand. Furthermore, Euro nations, especially in the Eastern side, are experiencing high levels of unemployment. Therefore, central Banks using the inflation target (2%) extracted by the Philips curve worked around the clock to pace inflation or fine-tune it to that target. Unemployment, a key variable in the Philips curve, was considered during the formation of monetary policies.

The unemployment rate after the Russia-Ukraine war reached an all-time high at 7.1% in the Eurozone. However, an essential factor in unemployment, vacancies, is written off at the cost of unemployment rates. The vacancy rate in the E.U. in the first quatre of 2022 was 3.1% because of labour demands and retirement. Additionally, previous structural changes adopted during the pandemic crisis promoted remote working, ease of changing a profession, and even maintaining a residence or moving. As of May 2022, unemployment rates in the E.U. were at an all-time high of 8.1%. Experts in countries like Moldova and Poland predict their unemployment rates will almost double in the upcoming year (Kilian & Zhou, 2022)

Conclusion

The Covid-19 pandemic hit the global economy with high inflation rates, and Central Banks had difficulty managing the inflation rates. However, Central Banks did manage to readjust inflation rates after the pandemic. After the Russia-Ukraine war, investors and company leaders began shifting from the Eastern Eurozone as regional distribution channels were severed. However, the common thing from the pandemic, war, Central Banks and economic uncertainty is inflation. The Russia-Ukraine war led to sanctions on Russia, and consequently, price shocks and supply chains were interrupted. Russia being a major metal and oil exporter, the demand for these items skyrocketed, and so did the price. Manufacturing and production processes were most affected by the oil prices. With oil being a massive player in the financial market and the general economy, prices of items increased, marking inflation.

The rise in oil led to an increase in energy prices, setting up economies for energy rations and repurposing energy. As a result, there needs to be better economic growth, low inventory, and slow supply chains. As a result, the inflation expectation was set up to rise. However, interceptions by the Central Bank through monetary policies as effective as they are can cause a decline in equity, and credit risk assets, which could consequently spread inflation to the housing and other sectors. Interventions by the Central Banks through monetary policies and interest rates proved inadequate yet less effective than intended. Monetary policies and concepts of the Philips curve and I.S. curves prove that these concepts are a work in progress.

References

Adrian, T., Erceg, C., & Natalucci, F. (2022, August 1). Soaring Inflation Puts Central Banks on a Difficult Journey. IMF. https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/08/01/blog-soaring-inflation-puts-central-banks-on-a-difficult-journey-080122

Domash, A. & Summers, L. H. (2022). A labor market view on the risks of a U.S. hard landing.

NBER Working Paper, 29910, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Mass.

Kilian, L., & Zhou, X. (2022). The impact of rising oil prices on U.S. inflation and inflation expectations in 2020–23. Energy Economics, 113, 106228.

Reis, R. (2022). The Burst of High Inflation in 2021-22: How and Why did We Get Here?. CEPR Discussion Paper, 17514, Centre for Economic Policy Research, London.

Prohorovs, A. (2022). Russia’s war in Ukraine: Consequences for European countries’ businesses and economies. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(7), 295.

Rochon, L. P. (2022). The general ineffectiveness of monetary policy or the weaponization of inflation. In The Future of Central Banking (pp. 20-36). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Ubide, Á. (2022). The Inflation Surge of 2021-22: Scarcity of Goods and Commodities, Strong

Labor Markets and Anchored Inflation Expectations. Intereconomics, 57(2), 93-98

write

write