Overview

If significant, long-term solutions are not found to the issue of homelessness in Seattle, the situation will probably continue to worsen. This is particularly true when it comes to helping individuals not just find but also maintain housing. For this purpose, there is a pressing want in the city of Settle for a well-thought-out policy that makes an effort to identify and emphasize the most effective long-term solutions to the issue of homelessness. It is crucial to emphasize that homelessness affects not only those who live outside in the harsh elements and on platforms made of hard cement but that its effect frequently extends much farther. Being homeless comes with huge expenses not only financially, but also morally and socially. This is especially true when considering the inherent human misery that is caused by the same thing and the possibility that is lost as a result of it being wasted.

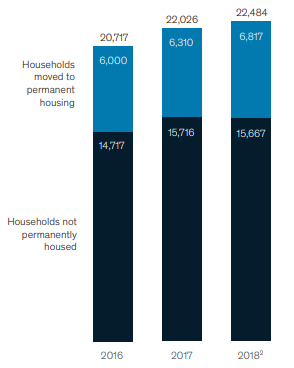

Significantly larger Seattle, like other rich regions in the USA, is presently in the bad spot of holding both vast quantities of riches and astonishing numbers of homelessness. This is a situation that no city in the world would choose to be in. Bill Gates and Bezos’s companies, whose two corporations have risen to be among the most profitable on the planet, both have their headquarters in the King County area, which has had an enormous financial increase in recent years and is home to both of these businesses. Nevertheless, although it is a significant economic powerhouse, the region is dealing with a homelessness crisis of immense proportions. In King County in 2019, more than 22,000 different households were affected by homelessness, and more than 4,000 children attending Public Schools were homeless (Maritz & Wagle, 2020). Even though there was a very minor decrease in the proportion of homeless people who were counted during the one-night Point-In-Time (PIT) census that took place in 2020, the overall high growth has not been reversed.

Figure 1: Homelessness in Seattle Source (Mckinsey Survey)

At first glance, it could seem as though King County already possesses all of the resources necessary to solve this issue. The region has both made substantial improvements in low-income housing, and together they have more than 4,000 additional units in the pipelines that are currently under development (Duber, Dorn, Fockel et. al 2020). There has been a commitment of huge amounts of money to the cause from huge companies as well as individuals. The knowledge has been shared with community leaders, and multiple strategies have been established. There is no shortage of vigor and passion coming from the group of volunteer workers. However, notwithstanding years of dedicated endeavor and the right attitude of public officials, industry experts, companies, and individual residents, the percentage of residents in the region that require homelessness services is continuing to rise.

The issue is getting even more serious

In 2019, the 22,000 households that received assistance for homelessness, signified an uptick from the previous year. The unfortunate fact that Seattle and King County, Washington, are among the top three regions in the United States in terms of the number of homeless people per capita gives them a questionable reputation (Mitchell et al 2020). In addition, the number of people who are homeless and do not have access to shelter has increased by 26 percent over the past year. Those who are now homeless represent a distinct segment of the overall population in this region.

According to Fynn (2019), the majority of people who are homeless in King County are classified to be ELI, which means that their income is less than thirty percent of the area median income (AMI). According to the reference point established by Housing and Urban Development, which indicates that a family should devote no more than thirty percent of its earnings to tenancy, the top range of this section receives approximately $23,500 per year and has the financial capability to pay approximately $6050 per month for shelter. at this price, Mckinsey reports that it’s impossible to locate a house in this region.

Reasons for Homelessness

According to Bell (2016), a significant contributor to the problem of homelessness in the area is the rapid economic expansion and accumulation of wealth in the neighborhood. Since a decade ago, the number of people employed in King County has expanded by 22 percent, while the population in the county has grown by 13 percent. However, the state has only expanded its housing supply by less than 10 percent over that same period. This disparity between demographic growth and job development has resulted in significant rises in rates all over the board—as much as fifty-two percent for various levels of residential accessibility. This type of phenomenon, which is known as a “fly up,” is typical in sectors like the property market where there is very little bargaining power of buyers and when availability is restricted. The decline in the accessibility and affordability of homes is a direct consequence of the demand (increase in demographics) surpassing the delivery. This imbalance has appeared although good efforts have been made to add housing at all scales, as well as specific activities that have been undertaken to provide accommodation that is accessible to people with low and intermediate incomes. The state has made complete use of the two most important government Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) schemes, which are often applied for the construction of affordable homes. There are more than 4,000 units in the planning stages for the city of Seattle, while the area is already developing more than a thousand units. However, Bell (2020) notes that this will not even come close to solving the issue by itself.

Some strategies that can end Homelessness

Integrated services and better coordination

It has been discovered that constructing a distinct service system for homeless persons from conventional programs is both costly and counterproductive (Rine & LaBarre, 2020). As a result of the lack of long-term strategic planning for housing stock and other critical procedures, initial homeless alleviation operations have been proposed. Although some temporary shelter will always be required, Seattle must have more than transitory solutions in place, no matter how varied or well-delivered they may be. There is a requirement for a tactical response. Long-term fundamental concerns necessitate standard programs that are tailored to suit the special requirements of homelessness. To reduce impediments to homeless persons accessing entitlements through mainstream programs, significant efforts are required ( (Rine & LaBarre, 2020). Institutional complexity and sector-specific financing, on the other hand, frequently thwart attempts to prevent homelessness and treat its consequences.

When specialized agencies establish organizational plans, they frequently focus on the issues and policy solutions that are most pertinent to their unique region of competence. Problems that occur across or span such jurisdictions appear to receive less attention. As a result, the organization of policy and planning is a critical factor in explaining variances in degrees of homelessness. Consequently, how interrelated governmental bodies, programs, and legislative ideas communicate and cooperate is vital for successful action against homeless individuals (Rine & LaBarre, 2020). To eliminate gaps and redundancy, and to get the most out of every investment made, inter-agency collaboration is essential. There are, nevertheless, numerous effective community-based models of integrated solutions linked to housing. These must be substantially enhanced on a much bigger scale to create a holistic range of services and housing.

Employment, business development, and community engagement

Employment, according to Dej, Gaetz, and Schwan (2020), is the foundation for most people’s economic well-being. Economic inequality and reliance are unavoidable without employment or a venture. As a result, many homeless-related programs include some form of business creation and training opportunities. These are often centered on activities for homeless people (such as guest housekeeper tasks or construction work on future housing) and are often just beneficial employment that is easily accessible for homeless individuals. Because many homeless persons in states work as garbage collectors, small traders, and other low-wage jobs, micro-finance can help them increase their production. In reality, their performance can grow to the point that they can become self-sufficient in safe housing, particularly if the financing also offers a space for established enterprises.

Conclusion

By fighting homelessness in an evidence-based approach, the Seattle area can act as a model for other port cities experiencing homelessness. The wealth of the neighborhood should serve as an incentive and trigger for constructive transformation. The joint objective should be to reduce homelessness to relatively low rates. Due to the reason that expenditures and continued attempts have been targeted at the symptoms of the issue rather than the underlying factors, the rich city packed with well-meaning, knowledgeable authorities is still trying to make homelessness a once-in-a-lifetime event for its inhabitants. In order to create development, the area should examine how it manages expansion and allocates resources. This can be done through integrated service and coordination as well as combating unemployment.

References

Bell, A. R. (2016). Thinking Past Tomorrow: An Analysis of Policy Efforts to Reduce Homelessness In King County, Washington.

Dej, E., Gaetz, S., & Schwan, K. (2020). Turning off the tap: a typology for homelessness prevention. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 41(5), 397-412.

Duber, H. C., Dorn, E. M., Fockele, C. E., Sugg, N. K., & Shim, M. M. (2020). Addressing the needs of people living homeless during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 26(6), 522-524.

Fynn Bruey, V. (2019). Development-induced displacement and homelessness in Seattle, Washington. Artha-Journal of Social Science, 18(2), 1-25.

Maritz, B., & Wagle, D. (2020). Why does prosperous King County have a homelessness crisis?. McKinsey & Company.

Mitchell, S. H., Bulger, E. M., Duber, H. C., Greninger, A. L., Ong, T. D., Morris, S. C., … & Pan, H. (2020). Western Washington state COVID-19 experience: keys to flattening the curve and effective health system response. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 231(3), 316-324.

Rine, C. M., & LaBarre, C. (2020). Research, Practice, and Policy Strategies to End Homelessness. Health & Social Work, 45(1), 5-8.

write

write