Japan is one of the leading countries in different spheres, with technology among the leading. However, the country’s aging population is a major concern for academic and non-academic commentators. Unfortunately, Macrotrends identifies that the country is experiencing severe demographic changes (par. 1). It has to contend with a rapidly increasing elderly citizen population and a declining birth rate. As a result, Japan is perhaps the most aged society globally. The demographic shift has far-reaching implications for the nation. This is so, considering the social, economic, and healthcare systems. The present paper seeks to establish how the Japanese government has (is still doing) responded to the challenges posed by an aging population, including the policies and initiatives the regime has implemented to address these issues. The report is based on a well-founded methodology, a literature review informed by a critical analysis. It is argued that while the Japanese regime’s efforts and policies are reasonable, it needs to adopt new models to address the aging population challenge and curb the subsequent impacts.

Population Trends in Japan

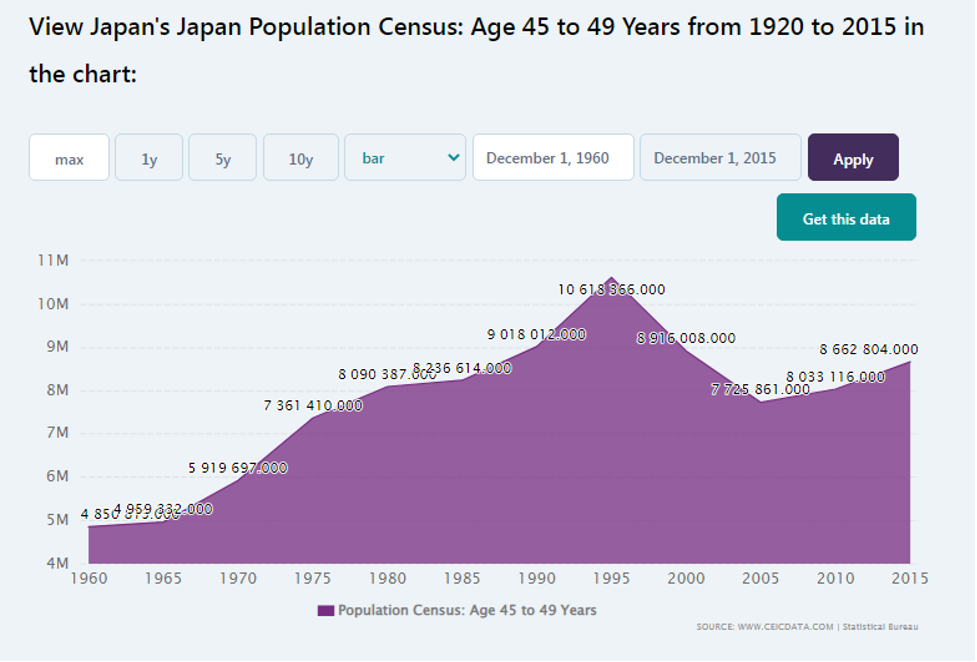

According to Macrotrends, Japan has experienced varying population growth rates across the years (par. 1). For example, Japan’s population was 82 million in 1950. However, fluctuations in the growth rate have been rife since then (Macrotrends par. 1). The 1970s marked the most undesirable turning point in the country’s history. This was a period when the increase in the aging population exceeded the birth rate. This trend is well-reflected in the 0.53% population decline from 2022 to 2023, reflecting the notion that the aging population has continued to increase while the younger population is declining. The Ceic Data indeed confirm this. Accordingly, the data shows that in 1920, the population in the 45 to 49 age group stood at 2,658,567 people (par. 4). This is the earliest recorded data point in the dataset. There has been a consistent increase in this population in several years after this era. In 2015, the population of people aged between 45 and 49 years reached 8,662,804, as seen in the image below (Ceic Data par. 6). This population is almost three times the number of people in the same age category in 1920. Hence, this vividly indicates a substantial increase in the number of aged people in Japan over almost a century.

The Social, Economic, and Healthcare Implication of Japan’s Aging Population

A larger elderly population in Japan implies a shift in family structures. More elderly individuals require intensive care, which easily leads to changes in family dynamics as adult children often take on the role of caregivers. Such a trajectory might cause stress among the Japanese offspring, potentially affecting career opportunities for those providing care. Besides, as the elderly population grows, the risk of loneliness and social isolation among the elderly increases, which is more likely to affect those living in rural areas where community structures are weakening. This can lead to mental health issues and a decreased sense of well-being. Hence, the aging population results in a shrinking labor force. As older individuals retire, there needs to be more younger workers to replace them, leading to workforce shortages in critical industries, prompting Japanese firms to recruit retirees who are well past their 70s (Matsui par. 1). As a result, economic productivity might diminish considering that aging laborers do not have the working energy and synergy that young workers might exhibit.

An aging population places a substantial burden on the healthcare system. Elderly individuals typically require more medical attention, leading to rising healthcare costs, as seen in Japan. WHO revealed that Japanese healthcare costs increase with age (6). As such, health expenditures start increasing steadily for every subsequent age group. Besides, the agency supposes that the per capita health expenditure for an average 80-year-old Japanese is 11 times higher than for an average 20-year-old. Such an outcome can strain government budgets and insurance systems. Furthermore, as the retiree population increases, the demand for pension and social welfare programs surges. Nikkei Asia reports that Japan’s social welfare spending is significantly high and will continue to be so. As such, it will reach 60% by 2040 (Nikkei Asia par. 1). Maintaining these programs while ensuring their sustainability becomes a challenge.

Economic productivity is also challenged because of the ongoing aging population. A shrinking labor force and the potential for a reduced workforce due to caregiving responsibilities can hinder economic growth. Japan’s declining birth rate and low immigration rates further exacerbate the situation. The nation faces the risk of a stagnant or declining economy, which has been confirmed across research. Komiya and Yamamitsu reveal that the country’s economy barely grew in the fourth Quarter OF the fiscal year ending 2022, leading to weaker consumption that raised significant policy challenges (par. 1). The report also claims that the Japanese GDP between Oct-Dec 2022 was +0.1% annualized (Komiya and Yamamitsu par. 1). This was well below the forecasted +0.8% level.

How Has the Japanese Government Responded to The Challenges Posed by An Aging Population, And What Policies and Initiatives Have Been Implemented to Address These Issues?

In light of the severe challenges posed by the aging population in Japan, the Japanese regime has made concerted efforts to curb them. A major part of this has been implementing policies. One of the most phenomenal moves has been the integration of Universal Health Insurance, commonly abbreviated as UHI. The system was introduced in 1961 as part of a comprehensive healthcare reform. The essence was to provide universal healthcare services for all citizens irrespective of their demographics. One of the core components of UHI is mandatory coverage for all Japanese residents (JHPN par. 1). It is essential to note that the policy covers Japanese nationals and foreign residents with a legal residency status. Therefore, nearly everyone living in Japan is automatically enrolled in the program. Another aspect of the UHI is multiple insurers. The system is not administered by a single government entity but by an amalgamation of different insurers. These insurers are primarily regional. Each client has an individual insurance provider. These insurers are known as “Kokumin Kenko Hoken)” (Mitaka City par. 1). The UHI program operates on a cost-sharing mechanism. Individuals and employers are responsible for paying premiums.

These premiums are typically based on income, with individuals contributing a portion of their earnings to the system. Employers also make contributions on behalf of their employees. Furthermore, the UHI system is organized into multiple tiers based on income levels. Lower-income individuals and families pay low premiums. Those with higher incomes pay more. This progressive system helps to ensure that healthcare remains accessible to all, regardless of financial status. Also, the UHI provides comprehensive healthcare coverage (JHPN par. Par. 5). It covers various medical services, including hospital visits, doctor consultations, surgery, prescription drugs, and preventative care. Dental and vision care are typically covered separately to address disparities in healthcare access. Another major feat of the system is high reimbursement rates, ensuring that medical facilities and professionals are motivated to participate in the design and delivery of quality care to insured individuals. Ultimately, the system assures support for vulnerable populations. As such, it includes provisions to support vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, including those with disabilities. These groups receive additional financial assistance to access necessary healthcare services. Thanks to the UHI, Japan is now the country with the longest life expectancy in the world (World Economic Forum par. 2).

Besides the UHI, the Japanese government has implemented the Long-Term Care Insurance program. This program was introduced in 2000 (JHPN par. 1). It is designed to address the growing aging population’s needs. The system provides coverage for people necessitating long-term care services. Such includes assistance with daily activities like bathing, dressing, and meal preparation. The LTCI system operates on a co-payment basis. The beneficiaries share the cost of care with the government. Eligibility for LTCI benefits is based on an individual’s functional capacity and care requirements. Services can be provided in various settings, including at home, community-based facilities, or nursing homes. The program emphasizes maintaining individuals’ dignity and independence while supporting those needing care. As Japan’s population ages, the LTCI program strives to ensure that elderly citizens receive the necessary long-term care services to enhance their quality of life. As a supplement to the Long-term Care Insurance program, the Japanese regime also promotes the concept of “aging in place.” Accordingly, the government accomplishes this cause by supporting home and community-based care services (JHPN par. 4). This allows elderly individuals to receive care in their own homes or within their communities. The essence of this practice is to promote independence and quality of life. The most immediate implication of the public pension system is the financial security it provides to elderly citizens. Retirees who have contributed to the system throughout their working lives can rely on these pensions to maintain a stable income in their retirement years. Besides, the public pension system is instrumental in preventing elderly poverty. Without a reliable source of income, many retirees could face financial hardship. The pensions help cover basic living expenses, reducing the risk of elderly citizens falling into poverty. Moreover, having a steady income from pensions ensures that elderly individuals can access healthcare services and afford medical expenses. It contributes to their overall well-being and health.

New Models to Address the Aging Population Challenge and Curb the Subsequent Impacts.

The Japanese government has been influential in addressing the aging population problem and the subsequent consequences. However, as long as the population ages, the current methods will produce less desirable long-term effects. Therefore, it is essential to carve out more innovative models.

One of the chief options is promoting active aging. This strategy can help keep the elderly healthier and more engaged in society. The government can invest in community centers, recreational facilities, and programs that cater to the elderly. This will allow the elderly in Japan to remain physically and socially active. The regime can advocate for several activities, including exercise classes, art and cultural programs, and volunteer opportunities. Another strategy is to embrace technology to enhance the lives of the elderly. Telemedicine for remote healthcare, home automation for safety and convenience, and digital literacy programs must be prioritized to ensure the elderly can navigate the digital world effectively. Such a measure will allow the elderly to access information relevant to their effective living more readily at low costs.

Intergenerational programs also come in handy. The Japanese government must encourage interactions between different age groups. Programs that connect younger generations with the elderly, such as mentorship programs, can benefit both parties. It can help reduce social isolation among the elderly and promote understanding between generations. Besides, the Japanese authorities must implement flexible work policies. These policies should support and encourage older individuals to remain in the workforce if they feel it is appropriate for them. Flexible work arrangements, part-time employment opportunities, and phased retirement can help retain the experience and skills of older workers. A relevant move is promoting aging in place. This strategy mandates the authorities to expand and enhance the concept of “aging in place.” They should invest in home healthcare services, accessible housing, and community support to allow older people to live independently in their homes for as long as possible.

Conclusion

Japan’s aging population presents a significant challenge with far-reaching implications for its society, economy, and healthcare system. While the Japanese government has made commendable efforts to address these challenges through policies such as Universal Health Insurance and Long-Term Care Insurance, the continuing demographic shift necessitates the exploration of innovative models for a sustainable and desirable long-term future. The Japanese government can consider promoting active aging, leveraging technology to enhance the lives of older adults, fostering intergenerational programs, implementing flexible work policies, and further enhancing the concept of “aging in place” to curb the problem more sustainably. These measures, coupled with continued assessment and adaptation of policies, can contribute to a more vibrant, inclusive, and sustained society that benefits all generations. Japan’s experience with aging population management is a valuable case study for other nations facing similar demographic shifts.

Works Cited

Ceic Data. Japan Population Census: Age 45 to 49 Years. 2023, https://www.ceicdata.com/en/japan/population-annual/population-census-age-45-to-49-years#:~:text=Japan%20Population%20Census%3A%20Age%2045%20to%2049%20Years%20data%20is,of%202%2C658%2C567.000%20Person%20in%201920. Accessed 6 November 2023.

JHPN. Long-term Care Insurance. 2023, https://japanhpn.org/en/longtermcare/. Accessed 6 November 2023.

Komiya, Kantaro and Eimi Yamamitsu. Japan’s economy barely grew in Q4, weak consumption raises policy challenge. Reuters, March 9, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/japans-economy-barely-grew-q4-weak-consumption-raises-policy-challenge-2023-03-09/. Accessed 6 November 2023.

Macrotrends. Japan Population Growth Rate 1950-2023. 2023. https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/JPN/japan/population-growth-rate. Accessed 6 November 2023.

Matsui, Motokazu. Nearly 40% of Japanese companies hire people over 70 years old. Nikkei Asia, August 13, 2023. https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Datawatch/Nearly-40-of-Japanese-companies-hire-people-over-70-years-old. Accessed 6 November 2023.

Mitaka City. Municipal Office Information. 2023. https://www.city.mitaka.lg.jp/foreign/english/003/006.html. Accessed 6 November 2023.

Nikkei Asia. Japan social welfare spending to rise 60% by 2040. May 22, 2018, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Japan-social-welfare-spending-to-rise-60-by-2040#:~:text=Annual%20outlays%20on%20programs%20including,on%20Economic%20and%20Fiscal%20Policy. Accessed 6 November 2023.

WHO. How will population ageing affect health expenditure trends in Japan and what are the implications if people age in good health? World Health Organization, 2020, https://extranet.who.int/kobe_centre/sites/default/files/How%20will%20population%20ageing%20affect%20health%20expenditure%20trends%20in%20Japan.pdf. Accessed 6 November 2023.

World Economic Forum. “Mainstreaming universal health, with Japan at the helm as a long-lived nation.” WEF, Dec 21, 2022. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/12/mainstreaming-universal-health-coverage-with-japan-at-the-helm-as-a-leading-health-nation/. Accessed 6 November 2023.

write

write