Section 1: What is Somatisation?

Somatization is the presentation of mental or emotional elements as somatic (physical) manifestations. For instance, some people experience headaches, nausea, back pain, chest discomfort, or exhaustion as a result of stress. Somatic symptom disorder and malingering are disorders in which somatization appears (Orzechowska 2021, p. 3159). The disorder is characterised as a mental illness with physical symptoms that have no known medical explanation. The less severe symptoms include headaches, nausea, bloating, diarrhoea, back or joint discomfort, trouble speaking or swallowing, and urine retention (Mewes, 2022). The most severe physical symptoms, such as seizures, balance issues, coordination issues, or paralysis, can render a patient incapacitated. Numerous studies have demonstrated that people with panic disorders are more conscious of their breathing and cardiac variations (Javelot and Weiner, 2022, p. 41). Somatoform comes in several forms, one of which is Catastrophizing Thinking. This essay analyzes somatization disorder, who it affects, its impact, how it is viewed medically and the theories that best explain the condition.

Then, a patient experiencing headaches will think they have a tumour, and someone experiencing dyspnea will think they have asthma. At this stage, many such patients often seek medical attention. Hysteria was claimed to stir up any medical disease in the seventeenth century. In contrast, somatoform diseases were thought to be a demonic possession and spiritual disorder of evil during the Middle Times. Freud defined hysteria as the “conversion of mental anguish into physical symptoms (Bogousslavasky 2020).” In addition to sharing genetic commonality with other mental diseases, such as eating disorders, somatic symptoms of illnesses have been related to internalising genetic risk factors. Defects in serotonin catabolism associated with somatization may lead to decreased blood tryptophan levels compared to controls.

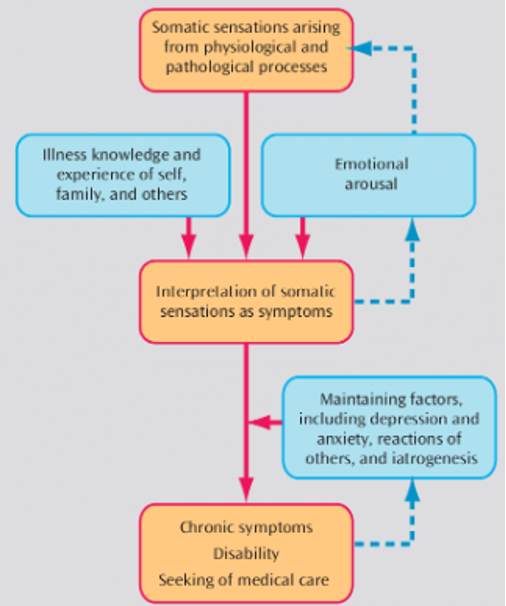

It is a clinical and public health concern because somatization can result in social dysfunction, challenges at work, and greater use of medical services. A concealed mental illness, an exaggerated personal perception style brought on by a personality characteristic, aberrant neuro-psychological information processing, or the need for medical attention owing to emotional discomfort can all be considered interpretations of somatization (Solvhoj et al., 2021). Pathophysiological mechanisms, genetic and developmental variables, cognitive theories, psychoanalytic factors, socio-cultural factors, gender, and iatrogenesis are some of the etiological elements to be considered. Pathophysiological mechanisms have three types: psychological, interpersonal, and physiological. Autonomic arousal, tense muscles, hyperventilation, vascular alterations, cerebral information processing, and disturbed sleep are some of the physiological causes that have been proposed. Perceptual, belief, emotion, and personality characteristics are significant psychological processes. Important interpersonal processes include the health care system, disability benefits, and the reaffirming behaviours of friends and family.

Victims of Somatisation

Somatisation mostly affects people who have been suffering from depression. Significantly, somatization has been the most common way for patients to arrive with depression in primary care (Davoodi et al., 2019). However, this type of bodily manifestation is thought to be a major contributing factor to the low rates of depression detection within this area of the healthcare system. Two kinds of depressed individuals who could be difficult to diagnose are consulted by general practitioners from the standpoint of primary care. Depressive comorbidity is common in patients with medical conditions. Because primary care clinicians’ diagnostic attention is primarily centred on a dominating concept of bodily disease, these related depressions frequently go undiagnosed. The way and degree to which depression manifests as physical symptoms might vary depending on several variables. Several investigations addressing diverse issues on multiple theoretical levels have established a strong correlation between somatization and female gender. The extent of manifestation of somatization in victims may usually depend on the extent of depression as well as the traumatic experiences that could have led to the depression.

Measurement of Somatisation

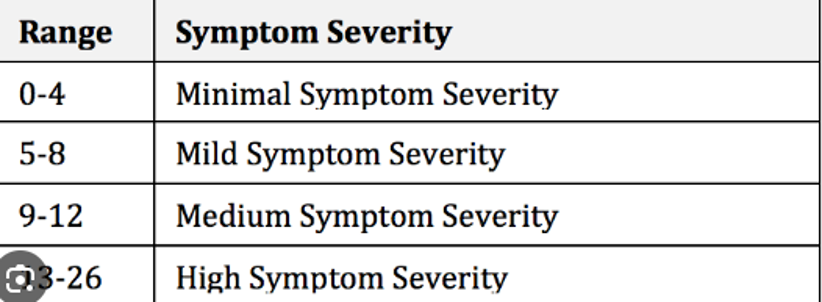

The PHQ-15’s somatic symptom module was used to quantify somatization. The items include the somatic symptoms of DSM-IV somatization disorder that are most commonly reported (Li et al., 2020, p. 5). For the previous four weeks, the subjects were asked to score the intensity of 13 symptoms as 0 (meaning “not bothered at all”), 1 (meaning “bothered a little”), or 2 (meaning “bothered a lot”) (Li and Zhang 2023). The PHQ-9 depression module includes two more physical symptoms: difficulty sleeping and feeling exhausted or low on energy (Zhou and Rief 2020, p. 11). Response choices for these two signs are coded as follows: 0 means “not at all,” 1 means “several days,” or two means “more than half the days” or “nearly every day” in terms of scoring. Accordingly, the PHQ-15 total score falls between 0 to 30, with values of ≥5, ≥10, and ≥15 denoting mild, moderate, and severe somatization, respectively (Tian et al., 2021). The PHQ-15 has high validity and reliability in clinical and professional healthcare settings.

Fig 1: PHQ-15 Scale for measuring somatization.

Several concerns manifest themselves in the diagnosis and treatment of somatization. For instance, patients with somatic symptom disorder usually see a primary care physician instead of a psychiatrist or another mental health specialist. This leads to the wastage of resources and time before the actual treatment of the condition can be commenced. In some cases, the patients may be unable to afford the treatment once diagnosed. Furthermore, people who suffer from somatic symptom disorder could find it hard to realise that their worries about their symptoms are unwarranted. Even after being presented with proof that they do not have a dangerous ailment, they may still feel anxious and afraid. This unbelief often causes the victims to lose a significant amount of resources in trying to seek further medical assistance for a condition whose treatment could be unhidden. For some people, the primary symptom of somatization is pain. The somatic symptom disorders also begin at the age of 30, an aspect that could influence a lot about the life events of the victims.

Section 2: How Somatisation Affects the Victim

The manifestation of somatic symptoms may vary depending on ethnic influences. For instance, it has been shown that somatization is most prevalent in South America and that Asians, particularly those who are depressed, are also prone to the illness (Garcia-Sierra et al., 2020, p. 577). The kinds of symptoms described have also been shown to differ by ethnicity. One symptom, a “heavy head,” for example, is far more frequent among Asians than in Americans, Caucasians, or Africans. Cultural and ethnic backgrounds may influence how people express themselves, whether for the better or worse, depending on the circumstances and how they handle stress or conflict. For instance, it may be improper for an elderly person in Thai culture to discuss their sexual desires, even with a doctor, as older individuals are typically held to higher ethical norms than younger ones. On certain levels, somatic symptoms may also be connected to psychological qualities like neuroticism. The tendency to perceive unpleasant ideas, such as irritation, worry, depression, or vulnerability, more readily is known as neuroticism. Other names for it include “negative affectivity,” “inverse emotional stability,” and “emotional instability.” One of the best indicators of somatism has been discovered to be neuroticism, and another personality feature that has been linked to the illness is alexithymia.

Furthermore, somatization ought to be common among people who exhibit social inhibition, which implies that it would be challenging to successfully ask for assistance from others or express themselves openly. Regardless of whether social withdrawal is associated with anxiety, despair, or even indifference, social inhibition is believed to represent complicated interpersonal behaviour connected to social withdrawal. However, social inhibition is more often considered a trait than a symptom, as evidenced by the interpersonal assessment of interpersonal issues.

Somatization is least highly correlated with symptoms of drug abuse and antisocial personality, but it is somewhat correlated with indications of schizophrenia and mania. It is also substantially correlated with symptoms of depression and anxiety (Cowan and Mittal 2021). Depression is the most prevalent comorbid condition linked to somatization in primary care. According to a comprehensive survey of primary-care patients, 69% of depressed people experience somatic symptoms, and a larger number of somatization symptoms is linked to a higher risk of depression (Fu and Guo 2019, p. 146). Somatization was still accepted as functional suffering in the absence of a biological substrate even though many mental diseases, like depression and schizophrenia, were thought to be biologically mediated. Prior research has noted certain anatomical alterations and functional disruptions in the brains of somatization patients; nevertheless, the neuropathology responsible for somatization symptoms in mental illnesses is still unknown.

Regional and illness-specific brain alterations have been shown in an increasing amount of research in recent decades to occur during the outset of mental and bodily illnesses and in those who are at risk for developing such diseases. Research on brain alterations in mental diseases that concentrate on differential diagnosis, severity of illness, and treatment outcome may have significant therapeutic implications. Brain function and gross morphological changes are the major causes of cerebral impairments; however, the changes may be slight, necessitating quantitative examination rather than merely ordinary visual assessment of pictures. Thus, it is imperative to create and apply quantitative noninvasive methods to track patterns of anatomical and functional alterations in the brain in mentally ill individuals. These discoveries contribute to our growing understanding of the neuropathy associated with mental diseases and offer guidance for the creation of objective, quantitative assessments of the patterns of aberrant brain activity associated with these disorders.

Anatomical abnormalities in the cortico-limbic-cerebellar circuit may impact the connection in individuals with somatic disorders (SD). In comparison with healthy controls, this results in structural modification in first-episode and drug-naive individuals with SD, which partially disrupts the connection of the cortico-limbic-cerebellar circuit. In individuals with somatic diseases, the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) measures cognitive function, and this performance is connected with structural change and connection impairments.

It is common to see insomnia coexist with somatic problems, such as discomfort. This special issue contains four pieces on insomnia. Wei et al. study how pain grows in tandem with the degree of insomnia when one has a restless night. Compared to those who sleep poorly, those with more severe chronic insomnia have higher mutual within-day pain sensitivity. Based on major depressive individuals with high or low insomnia and healthy controls, brain processes underlie the complex interaction between sleeplessness and depression. This suggests that the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations in the right inferior prefrontal gyrus insula rises with a greater resting state and may be directly connected to the hyperarousal state experienced by individuals with insomnia.

Section 3: How Somatisation is Viewed in the Medical Profession

The medical profession views somatization as a condition that easily attracts stigmatization, not only from those around the patients but also from some medical practitioners. Both stigmatisation and invalidation share essential characteristics, such as being seen unfavourably and lacking credibility. Even though these ideas are distinct yet related, they are frequently used interchangeably in literature. The multifaceted phenomenon stigma has several meanings. In the present investigation, stigma is defined as “a social process whereby social groups or individuals embrace, support,, or implement negative attitudes, typified by exclusion, rejection, blame, and devaluation, directed towards people with somatic disorders (Eggert 2023).” It has to do with a bad societal perception of a certain population, such as somatization sufferers. It’s critical to distinguish between the sensation of being stigmatised (experienced stigma) and the perception that one is being stigmatised by others (perceived stigma). When one internalises and applies the adverse perceptions and stereotypes associated with a health condition to oneself, it is known as internalised stigma (Chan and Tsui, 2022, p. 611). The phrase “invalidation” refers to a patient’s sense that others in their social surroundings do not acknowledge, accept, or even acknowledge their medical condition. There are two aspects to invalidation: discounting and a lack of comprehension. A lack of understanding reflects a lack of supportive social interactions, such as acknowledging, understanding, and providing emotional support for the patient. Discounting is a term used to describe aggressively negative social reactions, such as denial, reprimanding, downplaying incapacity to work, failing to recognise symptom variations, and providing useless guidance.

Significantly, the medical profession views somatization as a condition whose victims are often highly susceptible to stigma. The stigmatization could emanate from the immediate people to the patients and from other medical personnel. The latter group makes the patients feel abnormal, even haunted, in cases where such patients act increasingly abnormally.

On the other hand, the medical practitioners who often contribute to the stigmatization of the patient usually do so out of their negative attitudes while offering treatment to the patients. These factors contribute immensely to the element of stigmatization and shape the way and speed with which the patients embark on the recovery process from the conditions. In the bodily healthcare system, patients with somatism frequently report feeling rejected and undervalued by medical staff, and mounting data indicates that inequities in the delivery of healthcare are a factor in subpar health outcomes. Because of prevailing cultural beliefs, medical personnel who lack knowledge and competency about mental disorders have frequently been the first to initiate a process of stigmatisation in which they associate negative stereotypes and undesirable characteristics with patients who have mental disorders, creating a division between “we” and “they,” which causes the patients to suffer from discrimination, loss of status, and unequal opportunities and outcomes. Nonetheless, the identified research investigations show that somatic healthcare practitioners’ views towards individuals with mental problems are mostly reflective of societal attitudes.

In this sense, it appears that somatic healthcare providers behave in a stigmatising manner that is neither more nor lower than that of the general public. Crucially, and unlike members of the general public, medical experts have the authority to decide what kind, how, and under what conditions people with mental illnesses receive treatment. Because stigmatisation completely depends on access to the social, economic, and/or political power that permits the many components of stigma to emerge, power is essential to understanding stigma (Friedman et al., 2022, p. 408). Therefore, stigmatising attitudes and behaviours towards mental diseases among health professionals represent a serious issue that must be addressed as part of their continued professional growth during their education as well as continually during their careers.

Section 4: Theories On Social and Psychological Issues About Somatism

Psychodynamic Theory

According to psychodynamic theory, physical symptoms defend against unconscious emotional problems. Primary and secondary gain are the elements that cause and sustain somatic symptoms (Perotta 2020). While secondary benefits provide external motivators, primary gains create internal ones. Psychodynamic theorists claim that the main benefit about somatic problems is protection against anxiety, emotional symptoms, and/or conflicts (Luyten and Fonagy 2020, p. 130). This desire for defence manifests as a bodily symptom, such as headaches or discomfort. The secondary benefit, or the external experiences resulting from the physical symptoms that sustain these physical symptoms, might include but are not limited to compassion and attention, lost work, receiving financial aid, or mental incapacity.

The three primary components of our adult personality or self are the id, ego, and superego. The aspect of the self we are born with is the id, or the fundamental, primordial portion of the psyche (Kariimah 2022). It is made up of our instincts, desires, and the biologically motivated self. It’s the part of ourselves that demands satisfaction right now. Later in life, it becomes home to our most intense, frequently forbidden urges, including aggressiveness and sex. It functions according to the pleasure principle, which states that the sensation of something being pleasant or terrible is the standard for judging its morality. A baby is all an id. The next three years of a child’s life are when the ego starts to form. The superego, the final personality trait to develop, begins to show at about age five when a kid interacts with people more and more and picks up societal norms on good and bad. Our moral compass, or superego, serves as our conscience and instructs us on appropriate behaviour. It assesses our actions and aspires to perfection, which might make us feel proud or guilty when we don’t live up to our standards. The ego represents the logical aspect of our personality, in opposition to the automatic id and the rules-based superego.

It is the aspect of our personalities visible to others, and it is what Freud saw as the self. It functions according to what Freud dubbed the “reality principle”, as its role is to strike a balance between the id and superego’s needs within the reality framework. The ego assists the id in really satiating its needs. The superego forbids us from acting in a socially acceptable way, while the id demands rapid satisfaction regardless of the consequences, resulting in a permanent state of struggle between the two. Finding the middle ground is, thus, the ego’s task. According to Freud, a strong ego that can satisfy the needs of the id and the superego is a sign of a healthy personality. According to Freud, abnormalities in the nervous system might result in neurosis, anxiety disorders, or maladaptive behaviours. For instance, someone whose id is in control of them may exhibit narcissism and impulsivity. A person with a strong superego may experience remorse and even deprive oneself of pleasures that are considered socially acceptable; on the other hand, a person with a weak or missing superego may develop into a psychopath. An overly dominating superego can be observed in a neurotic who is extremely protective or in an overly regulated person whose cognitive grasp of reality is so solid that they are blind to their emotional needs.

Cognitive Theory

Cognitive theorists frequently hold that negative thoughts or heightened concerns about physiological experiences cause somatic diseases. People who suffer from somatic-related diseases could be more sensitive to their bodies’ feelings (Gustavsson and Siguroson 2021, p. 539). People with maladaptive cognitive habits and are sensitive to physiological symptoms may overanalyze and interpret them negatively (Bryant et al., 2022). For instance, someone with a headache can oversimplify its symptoms and assume that it is the direct outcome of a brain tumour rather than stress or another inflammatory cause. The patient may become even more terrified if their doctor does not validate this diagnosis, thinking they have an incredibly unusual condition that has to be evaluated by a specialist.

The field of psychotherapy known as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) developed from behaviourism, cognitive therapy, and acceptance and commitment therapy, among other cognitive behavioural treatments. The idea is predicated on the idea that a person’s perception of a certain occurrence influences how that person responds to it (Dijkstra and Nagatsu 2022, p. 828). The approach being discussed operates under the assumption that the patient’s negative and illogical reactions to tough situations, which manifest as thoughts, emotions, bodily symptoms, and behaviours, cause their difficulties. The goal of therapy is to alter behaviour and thought patterns as much as the patient feels is required. Three degrees of thought verification exist automatic thinking, presumptions, and fundamental beliefs.

Fig 2: Cognitive behavioural theory and somatoform disorder

The Theory of Mind

The capacity to deduce one’s behaviours and the mental states of others is referred to as the Theory of Mind (ToM) notion. To distinguish it from the affective ToM, which was used to characterise the capacity to infer others’ feelings, the aforementioned is sometimes called the cognitive ToM (Rusche and Glascher 2020). Deficits in the Theory of Mind have been identified in several conditions, including borderline personality disorder, schizophrenia, and autism. High alexithymia scores have also been observed in patients with somatoform disorder (Lankes et al., 2020). Therefore, it would seem that people with alexithymia often struggle to comprehend their thoughts and feelings and those of others, which might lead to maladaptive methods of controlling emotions.

Patients with somatoform illnesses have notable deficiencies in their Theory of Mind. More cognitive than affective ToM is measured in the SOCRATIS ToM domains. It has previously been reported that individuals with somatoform disorders had lower cognitive ToM than healthy controls. The Frith-Happé animation task and the Mental State Stories (MSS) were used to test cognitive ToM, and the results showed no significant differences between patients with somatoform disorders and medical controls. When comparing patients with somatoform illnesses to both healthy individuals and medical controls, it has been discovered that they have lower affective ToM.

Somatoform disorder patients struggle to deduce the mental or emotional states of both other people and themselves. Rather than a conscious perception of the emotion itself, this loss may lead to implicit expressions of emotional arousal, which are characterised by physiological and behavioural components (Rihacek and Cevelicek 2020, p. 545). Furthermore, people with somatoform disorders frequently experience interpersonal difficulties, which might be made worse by this. In turn, interpersonal issues might factor in the persistence of the physical discomfort.

Somatoform disorders frequently exhibit co-occurring anxiety and sadness. Therefore, we made an effort to look into how sadness and anxiety affected the ToM and emotional awareness impairments associated with somatoform diseases. In our study, even after adjusting for co-occurring anxiety and depression symptoms, there was still a group difference in ToM.

Section 5: Recommendations

One aspect that needs to be highly emphasized while undertaking the care and approach to patients with somatoform disorder is the comprehensive clinical interview and assessment for diagnostic criteria. Somatic symptom and associated disorders is the new term for the diagnostic category formerly known as somatoform disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). In order to make these illnesses more applicable in the primary care context, a better definition was the goal of this modification. Physical problems can be just as severe as somatic symptom diseases. Unnecessary testing and therapy may cause harm to patients with somatization whose doctors mistakenly believe they may have a biological illness. Patients with somatic symptom disorders can be bothersome to certain doctors, who may even use disparaging language when describing them. Even if they basically accuse somaticizing patients of fabricating their symptoms, they may accept physical diseases as real.

When a patient has a suspected somatic symptom condition, screening tools like the Patient Health Survey or the Somatic Symptom Scale-8 should be used. Somatic symptom disorder can be successfully treated with cognitive behaviour therapy and mindfulness-based therapy. For somatic symptom disorder, amitriptyline, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and St. John’s wort are useful pharmaceutical therapies. For the treatment of somatic symptom disorder, other antidepressants such as monoamine oxidase inhibitors, bupropion, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics are ineffective and are to be avoided.

There is a great need for collaboration between medical consultants for somatoform disorders and psychotherapy professionals. Such a collaboration will enhance effective treatment for the disorder, which will be vital in the recovery of the patients. The consultation will enable the treatment of the patients to span from a wide array of factors, which will hasten the recovery process. While offering treatment for the somatoform disorder, there is a need for an assessment of other medical and psychiatric diseases. The aspect will ensure that the patients receive a comprehensive treatment that will enhance their recovery.

The medical practitioner also needs to spend most of the time with the patient and persuade them that what they are feeling is real. This will reduce cases of increased depression and other vices that may otherwise slow down the treatment process. The aspect can best be done by emphasizing the connection between the mind and body of the patient. Significantly, to enhance a quickened treatment process, the medical practitioner needs to assure the patient that other medical conditions have been ruled out. The medical professional will also limit diagnostic testing and referral of the patients to other subspecialists.

References

Bogousslavsky, J., 2020. The mysteries of hysteria: a historical perspective. International Review of Psychiatry, 32(5-6), pp.437-450.

Bryant, E., Aouad, P., Hambleton, A., Touyz, S. and Maguire, S., 2022. ‘In an otherwise limitless world, I was sure of my limit.’† Experiencing Anorexia Nervosa: A phenomenological metasynthesis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, p.894178.

Chan, K.K.S., Fung, W.T.W., Leung, D.C.K. and Tsui, J.K.C., 2022. The impact of perceived and internalised stigma on clinical and functional recovery among people with mental illness. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(6), pp.e6102-e6111.

Cowan, H.R. and Mittal, V.A., 2021. Transdiagnostic dimensions of psychiatric comorbidity in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis: a preliminary study informed by HiTOP. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, p.614710.

Davoodi, E., Wen, A., Dobson, K.S., Noorbala, A.A., Mohammadi, A. and Farahmand, Z., 2019. Emotion regulation strategies in depression and somatization disorder. Psychological reports, 122(6), pp.2119-2136.

Dijkstra, J.M. and Nagatsu, T., 2022. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), and Morita therapy (MT); comparison of three established psychotherapies and possible common neural mechanisms of psychotherapies. Journal of Neural Transmission, 129(5-6), pp.805-828.

Eggert, K.F., 2023. Counsellors’ Lived Experience Treating Patients Utilizing Methadone: The Intersection of Culture, Policy, and Stigma (Doctoral dissertation, Antioch University).

Friedman, S.R., Williams, L.D., Guarino, H., Mateu‐Gelabert, P., Krawczyk, N., Hamilton, L., Walters, S.M., Ezell, J.M., Khan, M., Di Iorio, J. and Yang, L.H., 2022. The stigma system: How sociopolitical domination, scapegoating, and stigma shape public health. Journal of Community Psychology, 50(1), pp.385-408.

Fu, X., Zhang, F., Liu, F., Yan, C. and Guo, W., 2019. Brain and somatization symptoms in psychiatric disorders. Frontiers in psychiatry, 10, p.146.

Javelot, H. and Weiner, L., 2021. Panic and pandemic: a narrative review of the literature on the links and risks of panic disorder as a consequence of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. L’encephale, 47(1), pp.38-42.

Kariimah, C.A., 2022. ID, EGO, AND SUPEREGO OF THE MAIN CHARACTER OF THINGS FALL APART (1959) (Doctoral dissertation, Diponegoro University).

Lankes, F., Schiekofer, S., Eichhammer, P. and Busch, V., 2020. The effect of alexithymia and depressive feelings on pain perception in somatoform pain disorder. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 133, p.110101.

Li, Y., Jia, S., Cao, B., Chen, L., Shi, Z. and Zhang, H., 2023. Network analysis of somatic symptoms in Chinese patients with depressive disorder. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, p.1079873.

Li, L., Peng, T., Liu, R., Jiang, R., Liang, D., Li, X., Ni, A., Ma, H., Wei, X., Liu, H. and Zhang, J., 2020. Development of the psychosomatic symptom scale (PSSS) and assessment of its reliability and validity in general hospital patients in China. General Hospital Psychiatry, 64, pp.1-8.

Luyten, P. and Fonagy, P., 2020. Psychodynamic psychotherapy for patients with functional somatic disorders and the road to recovery. American Journal of psychotherapy, 73(4), pp.125-130.

Mewes, R., 2022. Recent developments on psychological factors in medically unexplained symptoms and somatoform disorders. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, p.1033203.

Orzechowska, A., Maruszewska, P. and Gałecki, P., 2021. Cognitive behavioural therapy of patients with somatic symptoms—Diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(14), p.3159.

Řiháček, T. and Čevelíček, M., 2020. Common therapeutic strategies in psychological treatments for medically unexplained somatic symptoms. Psychotherapy Research, 30(4), pp.532-545.

Rusch, T., Steixner-Kumar, S., Doshi, P., Spezio, M. and Gläscher, J., 2020. Theory of mind and decision science: Towards a typology of tasks and computational models. Neuropsychologia, 146, p.107488.

Sølvhøj, I.N., Kusier, A.O., Pedersen, P.V. and Nielsen, M.B.D., 2021. Somatic health care professionals’ stigmatization of patients with mental disorder: a scoping review. BMC Psychiatry, 21, pp.1-19.

Perrotta, G., 2020. Human mechanisms of psychological defence: definition, historical and psychodynamic contexts, classifications and clinical profiles. Int J Neurorehabilitation Eng, 7(1), p.1000360.

Tian, P., Ma, Y., Hu, J., Zhou, C., Liu, X., Chen, Q., Dang, H. and Zou, H., 2021. Clinical and psychobehavioral features of outpatients with somatic symptom disorder in otorhinolaryngology clinics. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 148, p.110550.

Zhou, Y., Xu, J. and Rief, W., 2020. Are comparisons of mental disorders between Chinese and German students possible? An examination of measurement invariance for the PHQ-15, PHQ-9 and GAD-7. Bmc Psychiatry, 20, pp.1-11. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12888-020-02859-8

APPENDICES

- Fig 2: Cognitive behavioural theory and somatoform disorder

- PHQ-15 Scale for measuring somatisation

write

write