Abstract

The role of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) is regarded to be essential for the monetary development of developed and developing market places. Because of this, the SMEs are appealing substantial interest of research. Particularly, with the enhancing significance of emerging economies on the international phase, the subject of international trade in the emerging economy SMEs is getting huge attention from practitioners and scholars. Moreover, the research of SMEs has participated considerably to the present literature of international trade. This study assesses the research questions that what is the role of networks and global value chains (GVCs) in increasing international trade among Chinese SMEs, what is the impact of COVID-19 on the international trade among Chinese SMEs, and what the policy perspectives are for Chinese SMEs regarding international trade. The findings of the study shows that the Chinese government has done a good job for SMEs in terms of international trade during COVID-19, but still, the exports of Chinese SMEs declined due to lockdown. Moreover, there have been different policies developed to promote international trade by the Chinese government.

Introduction

The role of SMEs is regarded to be essential for the financial development of developed and emerging markets. Because of this, SMEs are appealing substantial interest in research (Coviello, 2015). Particularly, with the enhancing significance of developing economies on the international stage, the subject of international trade in the emerging economy SMEs is getting huge attention from practitioners and scholars. Moreover, the research of SMEs has underwrittenconsiderably to the present literature of international trade (Lew et al., 2016).

Moreover, due to globalization, capitalism of network is increased and the economic activities are occurring in different networks of business conducted under complicated relations of the value chain (David &Halbert, 2015). However, the past studies do not entirely assess the impact of the role of international trade on the development of SMEs. Additionally, though SMEs are taking benefits from globalization, however, they also suffer from different problems that comprise fragile associations with weak innovation, external marketsin technology, and restricted financing (Khan et al., 2015) that can dishearten the growth of SMEs in terms of international trade.

Moreover, in the domain of China, most of the SMEs came around in the previous 15 years. With the inaugural of China to the market economy in the 1980s as a portion of the reforms, which are market-oriented started by head of China Deng Xiaoping and after that private SMEs were acknowledged as important to the economic growth of the country. The resultingmonetary reforms include state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in China and main SOEs rapidly transformed into small non-SOEs till 2004 (Xiangfeng, 2007).

In the meantime, more SMEs grew and spurred by the application of a promotion policy ofnon-SOE. After that, town and village enterprises (TVE) and urban collective enterprises along with self-employment and the private sector have been thriving and sprouting throughout China. The SMEs development has progressively contributed to the economic growth of China (Xiangfeng, 2007). They contribute more than 99% of all types of companies today in China. Additionally, the value of the output of SMEs contributes for a minimum of 60% of the gross domestic product of the country and generates more than 82% of opportunities for employment in China (Xiangfeng, 2007).

For SMEs, which are part of the service industry, the operating income is the source of capital. Once the SMEs will stop their operations, then there are chances that the source of capital will be done in. At the time of lockdown due to pandemics, the system of office of employees in the enterprises has also been transformed. To combine offline and online offices, SMEs need to have an entire system of the office online. The employees can allocate freely their time of working and the companies can be able to assess the employee’s performance based on the platform of online work (Su et al. 2022). Enterprise innovation is considered at the degree of technicality and in the device of system and management of innovation. Because of the restrictions of capital, SMEs still have to enhance their innovation(Su et al. 2022).

To face the situation of production and shutdown, investment decline, and sales difficulties are joined with the persistent pressure of unbending expenses like interest and rent amalgamated with other factors like the accounts payable expiry at the year-end, the SME’s survival stress is intensified further. The Small and Medium-sized Enterprises Development Index (SMEDI) in February was recorded as 76.4 points with a hugedecline of 16.2 points in comparison with the past month (Su et al. 2022).

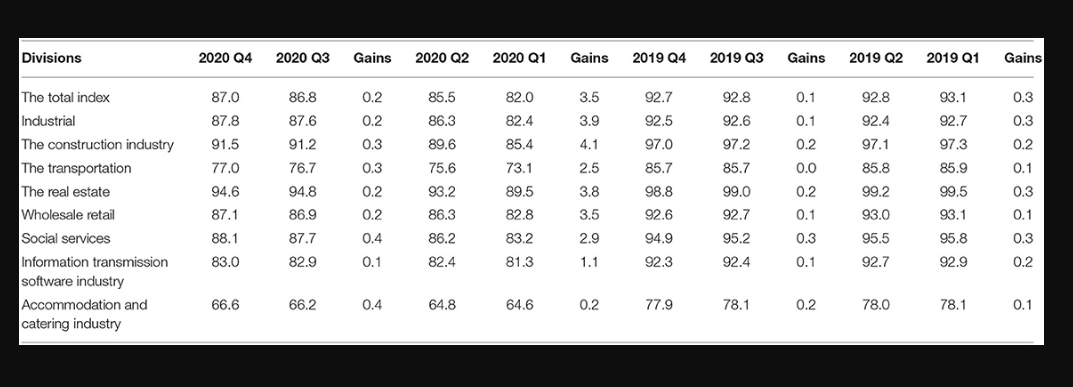

Additionally, under conventional conditions, the SMEs China life cycleis only 3.5 years. Under the impact of force majeure like COVID19, SMEhumanity might upsurge by 50% (Su et al. 2022). The government of China has quickly issued inclusive monetary policies to advocate sustainable development of SMEs to reduce the impact of the pandemic and that serves as an essential part of the economy.In this regard, there have been very limited studies conducted on the impact of international trade on the SMEs of China in the context of COVID-19. This is another research gap that will be addressed in this study. The quarterly gains of SMEs in China are shown below:

Table 1: Quarterly gains of Chinese SMEs in 2019 and 2020 Source:Su et al. 2020

Research Questions

Three research questions are addressed in this study:

• What is the role of networks and GVCs in increasing international trade among Chinese SMEs?

• What is the impact of COVID-19 on the international trade among Chinese SMEs?

• What are the policy perspectives for Chinese SMEs regarding international trade?

This study is helpful for the policymakers and strategists to make and devise policies for Chinese SMEs in terms of international trade. Moreover, while assessing COVID-19, this study has become more significant and impactful for SMEs in China.

Literature Review

History of SMEs in China

The first phase was from 1978 to 1992, which was marked by an increase in the number and magnitude of SMEs. This has resulted in government promotion and assistance for the establishment of a home, communal, and self-employment companies. The quick growth of these companies has made a substantial influence to economic development and the enhancement of people’s standard of living (Chen, 2006). The second phase extended from 1992 until 2002. The government has implemented various steps, like partnerships, mergers and acquisitions, leases, sales, and contracts to increase the reforms of state-possessed SMEs and to slowly diminish ownership of state of SMEs. Similarly, the privately owned SMEs liked fast development and the emergence of the economy of socialist market. The stage was a historically crucial time for the growth of Chinese SMEs. The 3rd phase commenced in 2002 (Chen, 2006). In June 2002, China published the Law for the Promotion of SMEs, which inaugurated a new era in the development of SMEs.Chinese SMEs have grown rapidly since opening and reform, whether based on size, volume, financial condition, or profitability. Two variables were critical throughout this period. The first factor was the speed with which municipal enterprises grew (Chen, 2006). The majority of firms in municipalities were small and medium-sized, and hence became the primary driver of Chinese SME development. Not only did the creation of urban firms facilitate the transfer of excess rural labor to non-agricultural sectors and enhance farmer income, but it also laid the groundwork for implementing the progressive development and reform approach. The second driver was the tremendous rise of the economy’s non-public sectors, particularly privately held SMEs. As economic reforms developed, an increasing number of people recognized the critical nature of non-state firms, particularly privately held SMEs. The government understood early on in the reform and opening process that the sector of non-public of the economy will be a compulsory and useful element to the public economy of socialists. China modified its constitution in 2004 to grant the private economy legal legitimacy inside the socialist market economy. This lawmaking action illustrates China’s growing awareness of the private sector of the economy, providing a significant boost to the development of privately held businesses (Chen, 2006).

Current status of Chinese SMEs

There were around 2.4 million SMEs operated in Chinacontributing for 99% of all types of registered companies. If those SMEs like leasehold farm households, self-employed businesses, and separate partnerships, which are not a lawful persons are also comprised the figure is far huge (Cardoza et al. 2015). The SMEs in China have played an essential role in inspiring economic growth, enhancing employment, increasing innovations of science and technology, and also increasing exports. Based on the economic expansion, the sales revenues, tax revenues, and output value of SMEs in the division account for 60%, 57%, and 40% correspondingly of the accumulated of all the firms of industry. SMEs have developed 75% of the increased industrial value of output (Cardoza et al. 2015). SMEs also subjugated in most of the sectors of industry and more than 70% of the value of gross output in the printing industries, food, and papermaking more than 80% in the recreation, garment tannery, plastic, and metalwork industries, and sports outfit of more than 90% in the furniture and wood industries (Xie et al. 2013). For instance, SMEs in the retail and wholesale industry contributed to around 33% of the accumulated number of SMEsand play a main role in increasing the movement of the commodity. Moreover, considering the expansion of employment, SMEs have developed around 79% of novel jobs nationally. Employees in the SMEs contributed for a huge percentage of the accumulated employees nationally and more than 85% in the sectors of industry, 90% in the industry of retail, and more than 65% in the industry of construction (Xie et al. 2013). Particularly, in the current years, the private-owned SMEs have increased employment and become the main force driving for the increase in employment, which plays a key role in fascinating laid-off and discrete workers from both urban collective enterprises and SOEs. Moreover, aroundworkers of 19 million were fired from SOEs and were employed again and the majority of them entered in SMEs. Moreover, in terms of foreign exports and trade, the accumulated value of exports of China was reported more than US$430 billion and it was tiered at 4th place in terms of the value of imports and exports. Additionally, on the list ofexport commodities, some unpackaged commodities of exports are majorly made by SMEs, like shoes and hats, garments, metal goods, handicrafts, toys and textile,and light industry products, which are mainly labor-intensive and high-tech products (Cardoza et al. 2015). Additionally, in the context of innovation of science and technology,Chinese SMEs have accomplished huge progress in the innovation of technology and become adynamic force for the application and spread of innovation and technology. Additionally, a huge frequency of technology-oriented SMEs traced in the regions like Waigaoqiao in Shanghai, Zhongguancun in Beijing, and the high technology and innovation zone in Shenzhen that donate greatly to the Chinese innovative technology.

Critical Analysis

Argument 1: Role of networks and GVCs in increasing international trade among Chinese SMEs

Uppsala’s model simplifies the process of internationalization by stressing gradual acquisition and integration of businesses based on expertise and incremental gains that result in increased market commitment participation in foreign markets, and promotion of international trade (Tian et al. 2018). However, the model has been challenged for failing to account for the worldwide trajectory of specific kinds of organizations, like international conglomerates that are born and internationalised early in their existence or have done so since their inception. According to Sandberg (2014), these types of process techniques are most frequently associated with large conventional manufacturing companies, and may not account for the quick increase of so-called international firms. The model of internationalization included networks by implying that a business insider would be a critical success factor for its globalization, as relations with diverse actors can result in knowledge transfer and creation (Lew et al. 2016). The business networks like supplier-customer ties serve as a dedicated experiential learning mechanism, facilitating the entry of businesses into new overseas markets, the establishment of new relationships, and promotion of international trade. Hilmersson and Jansson(2012) demonstrated the critical role of formal business networks in the development of business skills and market monitoring (Hilmersson and Jansson, 2012). Hoque et al. (2016) found that domestic social networks mediate the internationalization of businesses through exchanging knowledge about market prospects, trust, and learning. On the other hand, Ibeh et al. (2018) identified several official and informal networks, while promoting and aiding the process of internationalization, which can obstruct the development of businesses in a variety of ways.

The network is critical to the internationalization of SMEs, as it enables businesses to receive critical resources like learning and information through network ties (Khan and Lew, 2018). Social capital (SC) has a significant impact on the linkages between inter-organizational networks (Khan and Lew, 2018). SC is viewed as a valuable resource by enterprises since it enables business operations, internal processes, and value generation through resource sharing. The ability of businesses to construct SCs can significantly speed the generation of intellectual capital like new value propositions and innovations, both of which are critical components of internationalization. There are several studies carried out on the internationalization of SMEs utilizing SC. Resource sharing and knowledge through networks can result in mutual and even multiple profits for the various people involved in the transaction. Due to SMEs’ scarcity of resources like market knowledge and experience, they are compelled to seek complementarity network relationships (Lee and Gereffi, 2015), which are believed to exert significant influence on various stages of internationalization companies, including entry method, market selection, and process pattern and speed. Additionally, because of the adaptability and versatility of SMEs, they are excellent members of the network.

The governance constituent examines the dynamics of powerful players, power chains, and how these actors wield their power. Governance is described as the procedure through which influential participants in the supply chain specifically international purchasers monitor, establish, and enforce the requirements of production for their suppliers. By determining how, what, and when to produce the leading firms in established markets manage and organize the interactions of the value chain with smallholders in emerging markets (Liu et al, 2009). Chinese SMEs not only lack competitiveness in marketing, R&D, and brand development in comparison to the international giants but may also suffer from several other obstacles, including small size and modernity, that impede their quick internationalization.Their commercial connections with clients abroad are unequal with the latter wielding significantly more power than the former. Murray and Fu (2016) coined the term “quasi-hierarchy” which refers to a relationship in which one firm is superior to another. While participating in semi-hierarchical GVCs enables manufacturers of items and procedures to upgrade rapidly. It obstructs their advancement in design and marketing applications. The participation of Chinese SMEs in GVCs at the outset has paradoxical consequences like their indirect exports in international trade provide the input, but impede future development owing to a lack of knowledge or international relationships (Mudambi and Puck, 2016). As a result, Chinese SMEs’ ability to acquire market expertise may be constrained by their asymmetric network interactions with worldwide partners in the context of international trade.

Pla‐Barber et al. (2018) researchedChinese SME networks and internationalization and the study has concentrated on how networks assist Chinese SMEs inidentifying foreign opportunities,making market decisions, and establishing entry points. However, it is vital to assess the network’s quality and a company’s placement in the value chain to establish a very precise vision of Chinese SME internationalization (Musteen et al. 2014). Moreover, the first integration into GVCs shows that Chinese SMEs’ marketplace preferences were rather inactive, as they were required by multinational companies (MNCs) of developed nations that own the fundamental technology and know-how. For job management, business possibilities, and partnerships with local governments, Chinese SMEs mainly rely on informal networks to develop their market in international trade. Their efforts to diversify their businesses and grow their value-added operations exacerbate the demand for end-of-market network alliances. Additionally, Pla‐Barber et al. (2018) mentioned that it is a process of strengthening international commitments and commitments like product diversification and market that are driven more by the strength of international network links than their size. As a result, Chinese SMEs are expected to focus on strengthening their existing overseas networks rather than developing them to diversify globally (Ren et al. 2015).

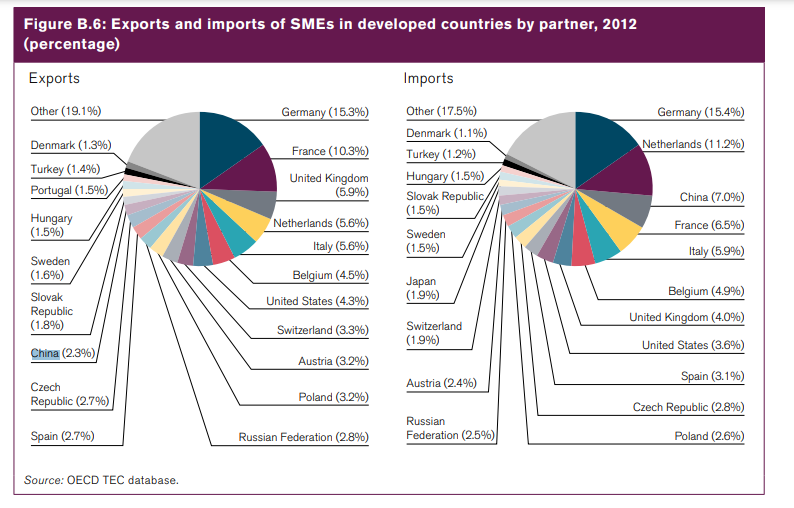

Due to the issues of network and internalization, the international trade of Chinese SMEs has been declined continuously. The SMEs share in the firms’ number that export to or import from India and China are declined than their trade share at the international level. However, the SMEs contribution to overall exports to India and China is greater in Portugal, Turkey, and the Czech Republic to overall import, which is greater in Latvia, Korea, the UK, Belgium, and the Netherlands. In all the nations, the SME’s importing share from China is higher than the SME’s share imported from India. Moreover, the huge majority of the SME exports of China in the developed nations are destined for other economies which are developed and most of the Chinese SMEs imports also originate in many developed economies. China is the exception as it accounts for 2.3% of the developed nation’s exports and 7% of imports (WTO, 2022). The shares of developed nations as partners of Chinese SMEsare exaggerated because intra trade of EU is involved in the chart. Moreover, the shares of China in imports and exports of the developed nation’s SMEs increase substantially to 7% and 22% respectively just like the shares of other markets, which are emerging like Russia, India, and Turkey (WTO, 2022). The below chart shows the imports and exports of SMEs in developed countries till 2012:

Figure 2: Imports and exports of SMEs in developed countries till 2012

According to the study of WTO (2022), it is identified Chinese SMEs typically export their products to 63 nations and Korean SMEs normally export to 57 nations.

Argument 2: Impact of COVID-19 on the international trade among Chinese SMEs

As an external force majeure influence, COVID-19 has a robust effect on the book value of companies. When the company’s book value is <0, the bankruptcy risk of the company increases the risk of cancellation of the inherent value. To avoid the internal value of companies from being cooperated by low book value, the government has to actively present support policies in a crucial period like a pandemic to help SMEs overcome operational difficulties and avoid macroeconomic development crisis and social stability because of the huge bankruptcies of SMEs (Lu et al. 2020).

Guo et al. (2020) that the government is the major external elements that influence the healthy growth of SMEs. Belitski et al. (2022) that legal systems, national policies and support policies have a substantial impact on the expansion of SMEs. Furthermore, during an era of great economic enlargement, the government may acknowledge this and give special policy assurances on the healthy growth of SMEs (OECD, 2009). However, the development of SMEs will be severely influenced by a range of policies of government and behaviours and a poor external business climate. In the case of Dai et al. (2021) responses from 45,000 companies in developing nations have shown that companies are not performing well during the pandemic in international trade due to heavy tax burdens, complicated lawful systems, and conclusive managerial processes, one of which key reasons for business sustainability. The World Bank survey (2020) also listed low faith in the system of judiciary, complicated tax systems, and rent demand for accessibility to public services as the key hurdles facing Chinese SMEs. All of the following negative outcomes stem from incorrect government policy. Therefore, in order to encourage the sustainable and healthy development of SMEs, the government should construct an effective legal and policy structure and a suitable tax system to minimise the cost of operating SMEs so that they can thrive in international commerce (Barkas et al 2020). Compared to large enterprises, Chinese SMEs have inferior anti-risk capability in case of force majeure. According to data from the Chinese SME Association, the SME development index in the first and second quarters of this year declined by 11.1 points and 7.3 points, correspondingly in comparison to previous year showing robust progress. The Pandemic has badly damaged SMEs. Therefore, SMEs have minimal power to fight pandemics and other force majeure situations and to deal with practical concerns such as insufficient liquidity and lack of money (Naradda et al. 2020).

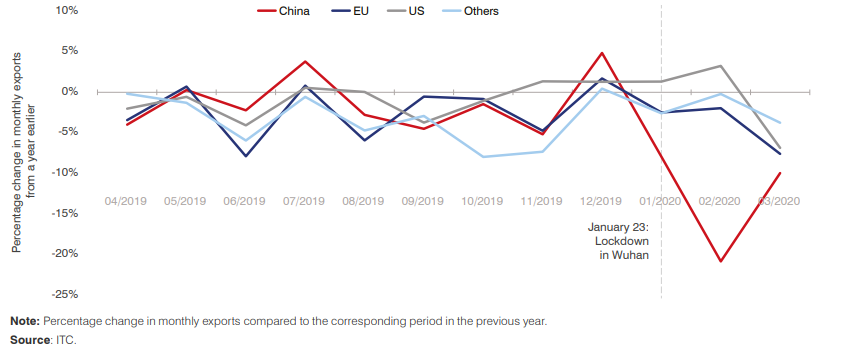

In the context of international trade, the monthly data of Chinese companies show that the exports of China decline around 21% in February 2020. Though, the exports of Chinese companies have recovered as the pandemic started to hit the exports from other nations. The decrease increased sharply with the arrival of a pandemic that caused the Chinese exports to drop steeply in the initial some months of 2020. Based on the monthly data of China, it is assessed that the exports of China to some nations were 21% lower in February as compared to February 2019 (Lu et al. 2021). In March 2020, the exports of China recovered slightly and that shows that they remained 10% below since March 2019. Moreover, as the pandemic hit other regions and nations later than China, the accessible monthly data reflects the starting of decline in exports.

Figure 3: Chinese exports decrease by 21% in February 2020 Source: Barkas et al. 2020

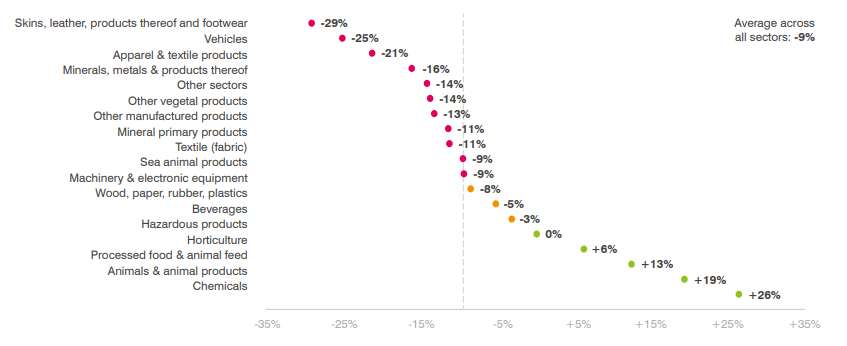

The decline of exports can also be witnessed through the below chart which shows that the exports of China are decreased during the pandemic:

Figure 4: Decline of exports of China during pandemic Source: Outlook, 2020

During a pandemic, the International Trade Center (ITC) makes deal with China to help the small businesses of the country to adapt towards a new normal reality. In this regard, ITC helps to conduct sessions of targeted training that help the small firms of China to be competitive exports. In response to the escalating situations of COVID-19 in China, ITC offers a sequence of sessions of remote training in March 2020. In collaboration with the School of International Governance Innovation, the training was a major component of a series of webinars known as ITC-China Month. These sessions provided the respondents with online tools of ITC and programs on trade. The trainees can carry out their regular activities in emergencies through webinars of video (Outlook, 2020).

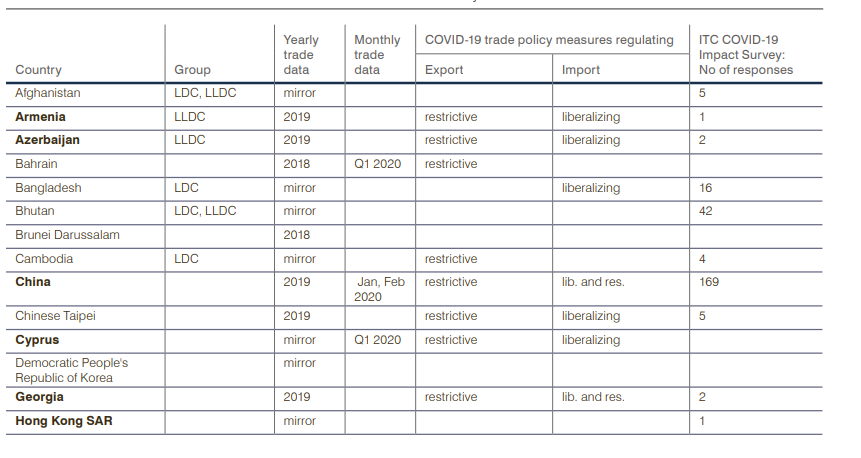

Moreover, for China in a pandemic, the exports were declined and the reason is very obvious because the exports of the country were very restrictive and imports were liberalized as other countries closed borders for China, as a result, the goods of the country cannot be shipped to other nations. It can be seen from the below table:

Table 2: Import and export situation Source: Outlook, 2020

Argument 3: Policy perspectives for Chinese SMEs regarding international trade

There have been different policy perspectives for SMEs in China regarding international trade. To get success in terms of international trade, the SMEs in China have to work on different aspects and as a result, different policies are devised and developed.

The first policy perspective is to improve service quality among SMEs and in this way, the government must ensure that publicly supported programs answer corporate requests, fix market flaws and deliver added value. It should also ensure that the business support network provides the specific service to firms. Policymakers of China at both the national and regional levels need to recognize that the process of company expansion has substantial policy implications for government services and determine strategies to address those issues regarding international trade. In addition to ensuring that employers receive quality training from universities and commercial organizations, training brokerage services are often vital for many small enterprises (Su et al. 2020).

The second policy is about learning from the experiences of the government of Jiangsu, which has promulgated the supporting policies on the small enterprise’s growth. These cover the innovation promotion, cover pioneering support, capital support, market expansion, rights protection, and service guide. The units of local government must insist on reforming the system of property rights and promote private and individual companies to become owners and shareholders of collective and state-ownedsmall enterprises. They must also promote enterprises of joint-stock, promote unequal ownership of the state, and reform the conditional enterprises of joint-stock into enterprises of standard company-system (Hänle et al. 2021). Moreover, the local government needs to increase and encourage the small enterprises to offer coordinative services for major firms and support the pursuit of activities of merger and acquisition. It must also reduce the small enterprise’s burden like some changes in the process of reorganization of companies, which can be subtracted.The local government of China must support the formation of a structure for technical innovation that allows for the absorption of technological development costs into the business budget, among other things. Profitable enterprises in national and collective industries might receive a 50% tax break if costs grow 10% more than the previous year (Su et al. 2020). Local governments should diversify their funding sources. Commercial banks should establish small business credit organizations. Credit guarantee money and risk capital must be located locally. Through equity and asset replacement, high-quality assets from small enterprises can be brought to the market for direct capital market financing. The local government should build a technological innovation service system geared toward small businesses, and information consulting center, a management consulting center, and a product distribution center (Xiangfeng, 2007).

SMEs in China normally face a regulatory structure that imposes substantial expenses in terms of time and money when working with government agencies. National reform may not be feasible in the short future. At the local level, as within a group of networks, the government is beginning to level the playing field in terms of the local government’s power to make local policy. This increases ownership and hence can shift the incentives of local governments away from neglect and toward engagement. The concern here is that such flexibility fosters more bureaucracy and corruption and also the growth-friendly red tape (Xiangfeng, 2007). A clear balance must be achieved between practical actions that create a favorable environment for the development and operation of a private company and regulatory requirements. If the established local level is successful, a real effort at the state and provincial levels, can be made. In this way, China has shown considerable success in its Special Economic Zone. The next step is to allow these zones to permeate into the broader macroeconomy. By fulfilling these guidelines and doctrines, the international trade of China is increased.

Another policy is related to the stimulation of inter-firm cooperation and the firms in China are organized as clusters frequently lack the cooperation of inter-company. When a cluster is a home to different competing firms, and even exceptional manufacturers and these companies have the potential to serve as protests of the best practice that might advantage other companies in the cluster. To start the non-competitive environment formed by the economy, which is planned centrally and in which each of the companies must cater a quota and bred complacency (Ibeh et al. 2020). These types of companies have no further spur to enhance the processes of production to the best practices and are unaware of their flaws of underlying to shield themselves from the internal competition. In this way, enhancing awareness regarding international trade, which is of the critical need for significant improvement has become a mandatory prerequisite for more intensive collaboration in international trade. It is not that simple for the businesses, which are operated previously independently to transit to close collaboration and this is not because of a lack of confidence, but also due to cooperation specifically from begin to finish and which result in adequate fixed and transaction costs. However, if government policy regarding international trade can stress the benefits of cooperation inside the network cluster, perhaps through fiscal incentives, cooperative transport may have a discounted value relative to its status quo survival. Alternatively, regulators can compare companies to other industries which can help companies understand how far behind industry leaders they are (Ibeh et al. 2020).

International technical progress has also been facilitated by the large influx of FDI into China. However, much of the foreign technology transfer that has occurred has been hampered by worries about intellectual property (IP) protection and the forced state of human capital, especially in the areas like control, quality management, logistics, and employee motivation. By addressing these two challenges, the networking organization is an effective vehicle for promoting both conscious transition and the unintended effects of international technological knowledge. By facilitating domestic technology transfer and enhancing worker training, human capital can be strengthened to assist international technology transfer in international trade (Lacka et al. 2020). Additionally, external sources of technical expertise can be accessed through the use of international consultants, licensing agreements between foreign and domestic enterprises, sending local workers overseas for training, and the establishment of associated multinational facilities getting into mentoring relationships with their local supplier chains and all of which benefit from a network cluster’s infrastructure and stability. When assessing investment projects, local intervention agencies may consider implementing a two-tier structure that differentiates between domestic and international firms, possibly granting tax benefits to foreign firms with advanced technological capabilities to improve international trade (Yang et al. 2014). These foreign firms can be integrated with domestic businesses in global supply chains, thereby encouraging domestic firms to update their knowledge bases. Without a doubt, a problem that should be considered in the medium and long term is the rights of intellectual property as this blocks international technology transfer and has been a recurring criticism since the accession of China to WTO. At this moment, China’s framework of intellectual property is compulsory at its best. Though there are strategic considerations, a person might argue that in the medium to long term, it requires to begin developing China to permit cheap usage of goods of IP with the low marginal cost of ownership of production, particularly in a developing country. Additionally, a comprehensive regime of intellectual property, particularly if indigenous research development is to be encouraged. The formation of cluster-specific IPOs might represent a step forward in terms of taking enforcement more seriously, particularly within the network cluster. IP breaches can be more easily discovered and enforced with regular encounters. This may eventually extend to the location of the regional IP strategy’s headquarters.

The implication of theory and practice and future policy and research

This study has some implications in terms of theory and practice. In practice, there are some consequences of the role of government in the formulation of strategies and policies for the international trade among companies of China. For theory, the role of government is to augment the debate on the institution’s impact, particularly to various policies of the public on the international trade among firms of China. Moreover, there are also some implications for practice and theory like they assess that SMEs perceive barriers and difficulties mainly in dealing with international trade like payment and exchange rates, logistics including paperwork and knowledge of global markets like familiarity, contacts, and info sources rather than with negative regulatory and inconsistent lawful frameworks (Fornes and Butt‐Philip, 2011).

Moreover, another implication is that the SMEs of China do not have much compulsory funding to enhance the operations globally and the private sources of funding are compulsory to the support from the government. These advocates from the private sources normally bring a transfer of skills and knowledge required to open in global markets (Deng, 2012). Additionally, these findings also have some implications for theory and they offer support that the international trade of the Chinese SMEs are based on the pull and push process, rather than they pushed only through a process of push focused on some strategic objectives in the developed companies. Moreover, another implication is that the ownership of state does not play a key role in encouraging the expansion of the firm to show that the strategic position of the companies must be weakened in a way they remain beholden to the approval ofthe administration and a legacy of reliance of institution and the Chinese entrepreneurs are restricted by unfavourable arrangements of institutions. Additionally, the outcomes developed are among the first to offer empirical evidence of the impacts of ownership of state on the global expansions of trade for SMEs of China. Moreover, the further implication is that the Chinese government as a customer has not evidenced to be a facilitator for the company to increase its international trade, however, the fact is that retail appears as a facilitator, which might indicate that the firms have a closer association with customers are in a better position to sell the products, which are beyond the borders of a country. In this way, the capability of serving and understanding customers is considered to be more robust than the probable advantages from the contracts of the government.The implications are based on the theory that excavates the understanding ofthe institutional role in the development of globally competitive SME business by offering evidence to augment the debate on the requirement to form a theory of management of China versus the requirement to form a Chinese theory of management (Warner, 2014).

Future Research and Policy

Considering the findings of this study, there are some future research areas developed. One of the major domains to deepen or broaden the assessments of companies of China would be continuing the research of the role of international trade on the development of SMEs in China and this is because complicated institutions web that infuses the economies which are developed is either absent, different or poorly developed in China (Cardoza et al. 2015). This becomes ostensible in three major areas which comprise information problems that comprise of reliable, comprehensive, and objective information that help to make decisions, which are not accessible widely. The second thing is about misguided regulations, which ensure that the goals which are political take priority on the economic efficiency that reduces and thus the chances to take complete benefit of business opportunities, and also ineffective judicial systems and the independence and neutrality of judicial system of China to impose contracts predictably and reliably has been questioned which will be assessed in further studies (Cardoza et al. 2015).

Conclusion

From the above findings, it is identified that in the context of China, most of the SMEs came around in the last 15 years. With the opening up of China to the market economy in the 1980s as a part of the reforms, which are market-oriented started by leader of China Deng Xiaoping and after that private SMEs were acknowledged as important to the economic development of the country. Moreover, it is assessed that the network is critical to the internationalization of SMEs, as it enables businesses to receive critical resources like learning and information through network ties. Social capital (SC) has a significant impact on the linkages between inter-organizational networks. During a pandemic, the International Trade Center (ITC) makes deal with China to help the small businesses of the country to adapt towards a new normal reality. In this regard, ITC helps to conduct sessions of targeted training that help the small firms of China to be competitive exports. In response to the escalating situations of COVID-19 in China, ITC offers a sequence of sessions of remote training in March 2020.

References

1. (2022) Wto.org. Available at: https://www.wto.or/english/res_e/booksp_e/wtr16-2_e.pdf (Accessed: 14 March 2022).

2. Barkas, P., Honeck, D. and Rubio, E., 2020. International trade in travel and tourism services: economic impact and policy responses during the COVID-19 crisis (No. ERSD-2020-11). WTO Staff Working Paper.

3. Belitski, M., Guenther, C., Kritikos, A.S. and Thurik, R., 2022. Economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurship and small businesses. Small Business Economics, 58(2), pp.593-609.

4. Cardoza, G., Fornes, G., Li, P., Xu, N. and Xu, S., 2015. China goes global: public policies’ influence on small-and medium-sized enterprises’ international expansion. Asia Pacific Business Review, 21(2), pp.188-210.

5. Cardoza, G., Fornes, G., Li, P., Xu, N. and Xu, S., 2015. China goes global: public policies’ influence on small-and medium-sized enterprises’ international expansion. Asia Pacific Business Review, 21(2), pp.188-210.

6. Chen, J., 2006. Development of Chinese small and medium‐sized enterprises. Journal of small business and enterprise development.

7. Coviello, N., 2015. Re-thinking research on born globals. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(1), pp.17-26.

8. Dai, R., Feng, H., Hu, J., Jin, Q., Li, H., Wang, R., Wang, R., Xu, L. and Zhang, X., 2021. The impact of COVID-19 on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): Evidence from two-wave phone surveys in China. China Economic Review, 67, p.101607.

9. David, M. and Halbert, D., 2015. Owning the world of ideas: Intellectual property and global network capitalism. Sage.

10. Deng, P., 2012. The internationalization of Chinese firms: A critical review and future research. International journal of management reviews, 14(4), pp.408-427.

11. Fornes, G. and Butt‐Philip, A., 2011. Chinese MNEs and Latin America: a review. International Journal of Emerging Markets.

12. Guo, H., Yang, Z., Huang, R. and Guo, A., 2020. The digitalization and public crisis responses of small and medium enterprises: Implications from a COVID-19 survey. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 14(1), pp.1-25.

13. Hänle, F., Weil, S. and Cambré, B., 2021. Chinese SMEs in Germany: an exploratory study on OFDI motives and the role of China’s institutional environment. Multinational Business Review.

14. Hilmersson, M. and Jansson, H., 2012. International network extension processes to institutionally different markets: Entry nodes and processes of exporting SMEs. International Business Review, 21(4), pp.682-693.

15. Hoque, S.F., Sinkovics, N. and Sinkovics, R.R., 2016. Supplier strategies to compensate for knowledge asymmetries in buyer-supplier relationships: implications for economic upgrading. European Journal of International Management, 10(3), pp.254-283.

16. Ibeh, K., Jones, M. V., and Kuivalainen, O. 2018. Consolidating and advancing knowledge on the post-entry performance of international new ventures. International Small Business Journal, 36(7), 741-757.

17. Khan, Z. and Lew, Y.K., 2018. Post-entry survival of developing economy international new ventures: A dynamic capability perspective. International Business Review, 27(1), pp.149-160.

18. Khan, Z., Lew, Y.K. and Sinkovics, R.R., 2015. The mirage of upgrading local automotive parts suppliers through the creation of vertical linkages with MNEs in developing economies. Critical perspectives on international business.

19. Lacka, E., Chan, H.K. and Wang, X., 2020. Technological advancements and B2B international trade: A bibliometric analysis and review of industrial marketing research. Industrial Marketing Management, 88, pp.1-11.

20. Lee, J. and Gereffi, G., 2015. GVCs, rising power firms and economic and social upgrading. Critical perspectives on international business.

21. Lew, Y.K., Khan, Z., Rao-Nicholson, R. and He, S., 2016. Internationalisation process of Chinese SMEs: the role of business and ethnic-group-based social networks. International Journal of Multinational Corporation Strategy, 1(3-4), pp.247-268.

22. Lew, Y.K., Khan, Z., Rao-Nicholson, R. and He, S., 2016. Internationalisation process of Chinese SMEs: the role of business and ethnic-group-based social networks. International Journal of Multinational Corporation Strategy, 1(3-4), pp.247-268.

23. Liu, J., Baskaran, A. and Li, S., 2009. Building technological-innovation-based strategic capabilities at firm level in China: a dynamic resource-based-view case study. Industry and innovation, 16(4-5), pp.411-434.

24. Lu, L., Peng, J., Wu, J. and Lu, Y., 2021. Perceived impact of the Covid-19 crisis on SMEs in different industry sectors: Evidence from Sichuan, China. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 55, p.102085.

25. Lu, Y., Wu, J., Peng, J. and Lu, L., 2020. The perceived impact of the Covid-19 epidemic: evidence from a sample of 4807 SMEs in Sichuan Province, China. Environmental Hazards, 19(4), pp.323-340.

26. Mudambi, R. and Puck, J., 2016. A GVC analysis of the ‘regional strategy’perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 53(6), pp.1076-1093.

27. Murray, J.Y. and Fu, F.Q., 2016. Strategic guanxi orientation: How to manage distribution channels in China?. Journal of International Management, 22(1), pp.1-16.

28. Musteen, M., Datta, D.K. and Butts, M.M., 2014. Do international networks and foreign market knowledge facilitate SME internationalization? Evidence from the Czech Republic. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 38(4), pp.749-774.

29. NaraddaGamage, S.K., Ekanayake, E.M.S., Abeyrathne, G.A.K.N.J., Prasanna, R.P.I.R., Jayasundara, J.M.S.B. and Rajapakshe, P.S.K., 2020. A review of global challenges and survival strategies of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Economies, 8(4), p.79.

30. Outlook, S.C., 2020. COVID-19: The Great Lockdown and its Impact on Small Business. SME Competitiveness Outlook.

31. Pla‐Barber, J., Villar, C. and Madhok, A., 2018. Co‐parenting through subsidiaries: A model of value creation in the multinational firm. Global Strategy Journal, 8(4), pp.536-562.

32. Ren, S., Eisingerich, A.B. and Tsai, H.T., 2015. How do marketing, research and development capabilities, and degree of internationalization synergistically affect the innovation performance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)? A panel data study of Chinese SMEs. International Business Review, 24(4), pp.642-651.

33. Sandberg, S., 2014. Experiential knowledge antecedents of the SME network node configuration in emerging market business networks. International Business Review, 23(1), pp.20-29.

34. Su, F., Khan, Z., Kyu Lew, Y., Il Park, B. and ShafiChoksy, U., 2020. Internationalization of Chinese SMEs: The role of networks and GVCs. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 23(2), pp.141-158.

35. Su, W., Guo, X., Ling, Y. and Fan, Y.H., 2022 China’s SMEs Developed Characteristics and Countermeasures in Post-Epidemic Era. Frontiers in Psychology, p.313.

36. Tian, Y.A., Nicholson, J.D., Eklinder-Frick, J. and Johanson, M., 2018. The interplay between social capital and international opportunities: A processual study of international ‘take-off’episodes in Chinese SMEs. Industrial Marketing Management, 70, pp.180-192.

37. Warner, M., 2014. Understanding Management in China: Introduction. Routledge.

38. Xiangfeng, L., 2007. SME development in China: A policy perspective on SME industrial clustering. Asian SMEs and Globalization”, ERIA Research Project Report, 5.

39. Xie, X., Zeng, S., Peng, Y. and Tam, C., 2013. What affects the innovation performance of small and medium-sized enterprises in China?. Innovation, 15(3), pp.271-286.

40. Yang, J., Yang, N. and Yang, L., 2014, June. The Factors Affecting Cross-border E-commerce Development of SMEs-An Empirical Study. In WHICEB (p. 12).

Appendix

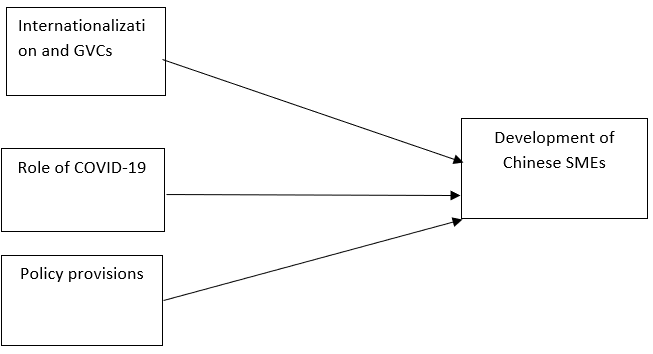

Source: Author’s illustration

write

write