Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic has had adverse impacts on individuals and affected nearly all aspects of life. From social and economic disruptions to food insecurity, loss of livelihoods, loss of loved ones, and devastating effects on education, Covid-19 has affected the general well-being of individuals. From a personal point of view, the pandemic fundamentally changed my ways of doing things and shaped my behavior in several ways. For example, it completely changed my perspective towards spending, shopping, and saving. More than ever before, I pay special attention to creating multiple streams of income, prioritizing my health and that of my family. Today, I am more conscious about making sustainable choices than short-term decisions. This paper highlights and discusses at length the specific ways through which the pandemic affected my life.

Introduction

The outbreak of Covid-19 has affected people’s lives in unprecedented ways. The pandemic has had devastating social and economic disruptions that threatened our lives. Whether it is restrictions on movements, school closures, ban on social gatherings, or limitations on certain economic activities, the pandemic has created many negative effects. The overall effects of these social and economic disruptions are loss of income, food insecurity, loss of lives, and increased poverty levels (Horton, 2021). The security measures imposed and social distance requirements also affected relationships and social interactions among people. It is almost impossible to find someone whose life was not affected in one way or another due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Thus, from a personal point of view, the pandemic altered almost all aspects of my life, including loss of income, loss of loved ones, changes in behavior patterns, loss of education, restricted movement, and high cost of living. Overall, the pandemic dramatically changed my way of living, working, and learning in unprecedented ways.

Loss of Income

One of the greatest impacts of coronavirus is the financial impact that weighed heavily on me. The economic disruptions forced many employers, whether small, medium size, or large to cut salaries of employees temporarily due to loss of revenues during the pandemic. A considerable number of companies turned to pay cuts rather than laying off workers to reduce their labor expenses, and my employer was no exception (Buheji & Ahmed, 2020). My company implemented a 40% pay cut for all employees in March 2020, hoping to preserve the existing workforce for a faster recovery. Although the approach made economic sense, particularly during those uncertain times, it affected my lifestyle and general spending habits. During the 1 year of a pay cut, I had trouble paying my bills, including servicing a bank loan that I had taken a couple of years ago. The loss of income meant that I had to dip into personal savings at least to make ends meet. At some point, I had to borrow money from family members and friends to cover some of the expenses. The financial struggles during the period were a result of job disruption. In addition, the loss of income curtailed my ability to save money due to the economic upheaval.

Besides the financial impacts, pay cuts have effects on morale and overall productivity. Taking away a portion of employees’ income suddenly lowers their morale, especially if they are expected to do the same duties for less compensation (Cortes & Forsythe, 2020). During the period of the pay cut, there was a general feeling of low morale in the workplace. Decreased morale comes with lower productivity. Employees did not feel motivated to work hard for less pay, so the reduced productivity further affected the normal operations of the business. The overall effect of lower morale and decreased productivity was a decline in the quality of work due to the lost benefits and incentives. Pay cuts also come with reduced loyalty as employees are generally uncertain about what may come next. The overall effect is that employees start listening to offers from other potential employers due to the reduced loyalty.

Loss of Loved Ones

Coping with the loss of a loved one is often difficult, but it was even harder during the Covid-19 period because the losses were sudden and families were unable to mourn properly due to the restrictions meant to stop further spreading of coronavirus. On several occasions, I could not memorialize and grieve the loss of a loved one in ways that are culturally and religiously normal (MacKenzie, 2020). Border restrictions, both at the national and international level meant that I have had to forego attending funerals of a couple of my loved ones. In addition, visiting loved ones in hospital, particularly those infected with coronavirus was almost impossible. Not being able to be with a loved one or attend their funeral only made it difficult to deal with the loss. In my culture, rituals play a critical role in the grieving process as they enable the bereaved to connect with their loved ones. These rituals include being with a loved one at the end of life, attending their funeral, and interacting with others who are close friends and family members. These rituals not only help in the management of emotions but also help the bereaved to accept grief.

Losing loved ones and not being able to attend their funeral during the Covid-19 era affected my ability to process their loss. For example, I experienced frequent and ongoing thoughts after losing my grandmother and not being able to attend her burial. I was constantly preoccupied with sorrow, excessive bitterness, and anger. I experienced a disconnection from a number of social relationships for several months because I had difficulties accepting her death. The thought of helplessness and hopelessness stuck me for a whole year and had significant impacts on my day-to-day functioning. Even after the lockdown restrictions were lifted, funeral services have been quite different during the coronavirus era (MacKenzie, 2020). For example, the restrictions of the people who can attend meant that I had to miss attending the funeral of colleagues and close friends who died during the pandemic period.

Working from Home

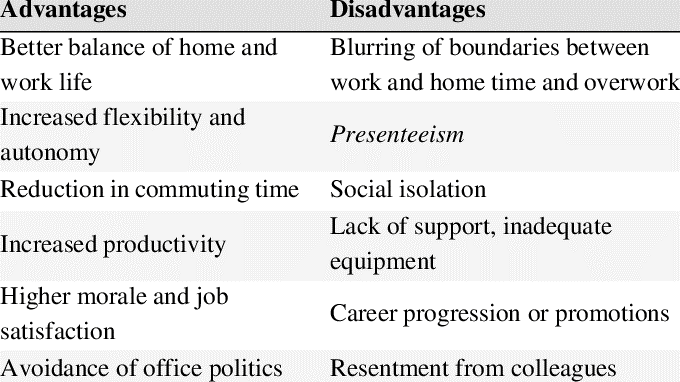

The outbreak of Covid-19 led to a significant percentage of the workforce being unable to go to workplaces in effort to mitigate the spread of coronavirus. This made employers and employees look for alternative working arrangements, particularly in densely populated metropolitans like Nairobi. Most employers resorted to working from home (WFH). This working arrangement has had its limitations and huge impacts on employers and employees. From an employee’s point of view, working from home saves commuting time and gives employees some level of flexibility (Green et al., 2020). It allows them to choose the times to work when they are most productive and to take care of their families the rest of the time. A major concern for this kind of arrangement, however, is the inability to balance work schedules and family engagements. From the employer’s point of view, working from home limits teamwork, which is necessary for effectiveness. Working from home is also criticized due to lack of motivation which affects the achievement of desired organizational goals. Unmonitored performance is another challenge that employers face in working from home arrangements, which may lead to less amount of work being accomplished.

Although working from home offered me some level of flexibility and autonomy, I lacked sufficient emotional support to handle stress during work. The loneliness experienced while working from home is too much and could lead to depression, damage to relationships, and other ills. Working from home was associated with depressive symptoms and decreased social satisfaction. As far as happiness is concerned, computers cannot substitute the in-person interactions that come with working from the office (Green et al., 2020). Although working from home is a good substitute for working from the office during the pandemic, it is inadequate in terms of addressing the human needs for interaction. Overall, this working arrangement had negative impacts as far as mental health is concerned.

Table 1 shows the advantages and disadvantages of WFH. Source ((Green et al., 2020)

Restricted Movements

In March 2020, Kenyan authorities issued tight restrictions in Nairobi and other parts of the country after an increase in the Covid-19 infection rate. All movements by air, road and rail into and out of Nairobi and other major cities were suspended. In addition, curfew was imposed between 10:00 pm and 4:00 am for the entire nation. The operation of certain businesses such as bars and restaurants was further suspended in response to the increasing number of coronavirus infections. These strict measures further crippled the economy and the cost of living in Kenya. The lockdown had far-reaching effects on the physical and mental health issues like anxiety and depression. During the lockdown, there were increased levels of stress and psychological problems due to many uncertainties. The stress was linked to the disruptions in the normal ways of living, learning, and working. Besides these disruptions, the lockdown caused a lot of fear and panic. For instance, the fear of being infected, long a loved one, losing a job, and fear of financial instability. The uncertainties about the next move the government would take further intensified the emotional difficulties.

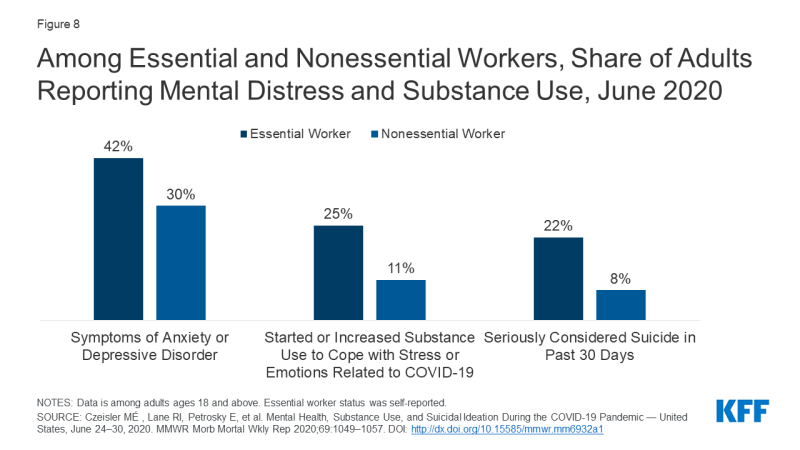

At a personal level, the thought of the number of people who lost their lives during the lockdown period coupled with an uncertain future, social isolation, and lack of access to certain amenities affected my mental health and almost led to depression. The mental health issues can be attributed to the loss of income and the uncertainties that came with the lockdown. People with lower incomes are more likely to experience mental health impacts compared with those with higher incomes. In addition, working in the essential services sector further intensified the situation. During the lockdown period, essential workers were required to work outside the home and could not practice social distancing due to the nature of their job. Consequently, I was at a higher risk of contracting coronavirus and exposing other members of my family (Panchal et al., 2020). As an essential service provider, we faced more challenges including access to Personal Protective Equipment (PPEs). Combined, these factors may have contributed to poor mental health outcomes for me and other essential service workers. During the pandemic, essential service providers were more likely to show symptoms of anxiety and depression than non-essential workers.

Figure 1 shows symptoms of anxiety and depression on essential workers. Source (Panchal et al., 2020)

Loss of Education

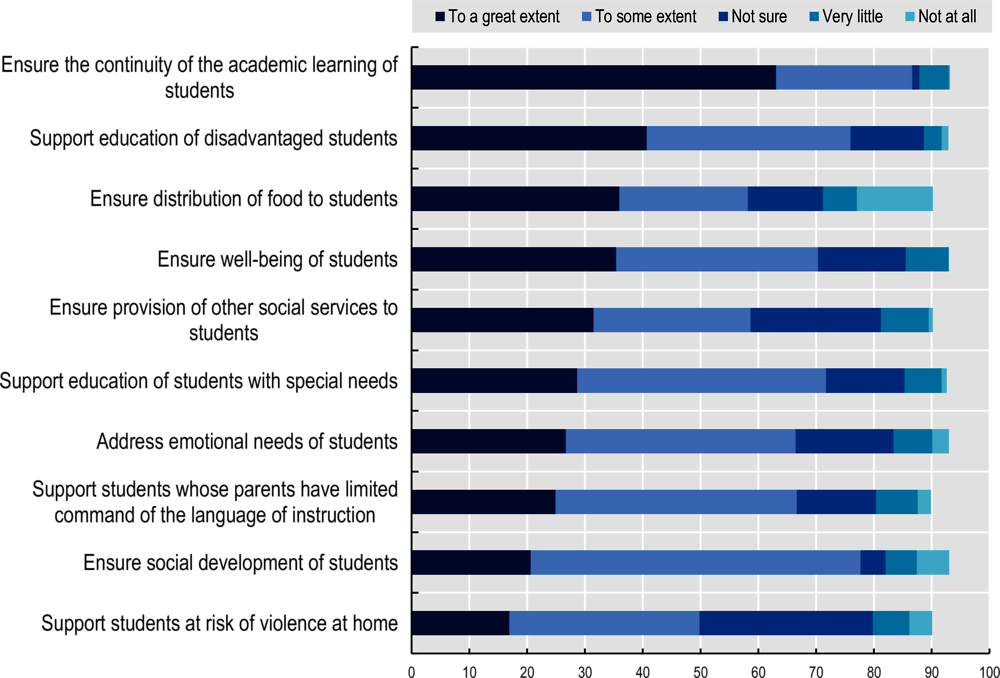

The government of Kenya closed all schools, colleges, and universities to further reduce the spread of coronavirus. As a result, learning institutions were required to use technology and the internet to implement online learning. Teachers were also required to prepare learning materials to facilitate learning at home. However, the lack of access to the internet, particularly in remote areas hindered effective online learning (Hoffman & Miller, 2020). The closure of learning institutions not only affected learners, but also affected parents, teachers, and other stakeholders. It led to the loss of learning time as students had to stay at home for over 7 months. As a result, a learning gap emerged and affected the normal January to December calendar for primary and secondary schools. At a personal level, my children had to stay without receiving education during the period and had to wait for the reopening to continue with their studies.

Being out of school meant the cessation of learning for my children, so they had to be engaged in domestic chores. Studies show that domestic responsibilities increase the risk of academic failure. The prolonged school closure further took a toll on students’ physical and emotional well-being (Hoffman & Miller, 2020). Besides academic support, schools are essential as far as the provision of non-academic support is concerned. The non-academic support is in the form of mental and health support such as obesity prevention. In addition, children have a wide range of mental health needs that are often addressed through school-based services. School counselors and psychologists play a crucial role in the provision of mental health services (Hoffman & Miller, 2020). Schools are the most ideal places for children to obtain mental health needs, so the prolonged closure denied children these services. During a prolonged school closure period, parents were forced to assume the role of educating their children, while also working, which was quite challenging. Children’s mental health was further affected by exposure to a wide range of societal changes like social distancing, exposure to pandemic-related information, some of which were frightening.

Table 2 shows the importance of educational continuity. Source ((Hoffman & Miller, 2020)

High Cost of Living

When the Covid-19 pandemic struck in 2020, the government reduced taxes on basic commodities such as gas and cooking oil to 14% to cushion Kenyans against the economic shocks. However, in 2021, the government re-introduced the 16% tax on gas and cooking oil, even before the economy had fully recovered from the economic shocks of the pandemic (Voigt, 2021). The action by the government further raises the cost of living. Further to re-introducing taxes on gas and cooking oil, the government also increased taxes on airtime from 15% to 20%, affecting over 21 million subscribers. Kenya also increased borrowing to try and cushion Kenyans against the effects of the Covid-19, which only added more burden on Kenyans. The government has continued to borrow to finance major infrastructural projects happening in the country. Excessive borrowing puts pressure on the government’s income, so the government has to turn to Kenyans to fill the income gap. The high cost of living is felt more by the poor who spend most of their income to buy food items and housing. The situation is further worsened by massive corruption in the government, so funds that would otherwise be used to service the national debt are lost through corruption.

The massive corruption in Kenya has had far-reaching effects. Besides increasing the cost of living, it increases the cost of doing business. The Covid-19 pandemic further intensified the crisis, making it extremely difficult for low income earners and small businesses to survive. The situation is not expected to change soon given that Kenya is in the electioneering period and the economic outlook is not optimistic (Voigt, 2021). Elections in Kenya have previously been associated with a poor economic outlook and reduced investments since no investor is willing to invest in a country where there are uncertainties such as violence. Furthermore, no significant policies are made during the election period since legislators focus more on elections than anything else. Chances of a rapid economic recovery post-pandemic look slim, meaning that the cost of living will continue to skyrocket in the foreseeable future. Thus, the pandemic has not only increased the cost of basic commodities in Kenya but also made life completely unbearable.

Limited Access to Natural and Nutritious Foods

The lockdown and border restrictions slowed harvests in some parts of the country, leaving millions of people, particularly in the urban settings without access to natural and nutritious foods. The restrictions on movements further affected the transportation of foods to the market and forced many manufacturing plants, particularly those located in rural areas to close down (Stephens et al., 2020). During the lockdown, many farmers dumped perishable produce like vegetables and milk due to disruptions in the supply chain and declining consumer demand. People in urban settings, on the other hand, struggle to access nutritious commodities like milk, fish, meat, fruits, and vegetables. Trade restrictions and other confinement measures not only prevented farmers from accessing markets for their produce but also barred them from buying farm inputs. Agricultural workers were also affected, which further altered the timely harvesting of crops, thus interrupting the entire food system. As a result, urban dwellers like myself and my family faced limited access to healthy, nutritious, diverse, and safe food items.

The pandemic affected the whole food system and showed its fragility. In a country characterized by high levels of poverty like Kenya, Agriculture is one of the greatest contributors to the economy’s GDP. The lockdown, therefore, posed a great challenge to the food production process, contributing to food insecurity for all people (Stephens et al., 2020). The situation was further exacerbated by a lack of government support to the agricultural sector due to declining revenues. In addition to border and trade restrictions, quarantine measures imposed by the government also limited farmers’ ability to access their lands for harvesting. As a consequence, crop production declined further leading to food insecurity in the long run. In the urban areas, border and trade restrictions affected formal and informal trade of agricultural produce. The overall impact was a rise in the prices for agricultural products, limiting access to natural, nutritious, and safe products.

Changes in Behavioral Patterns

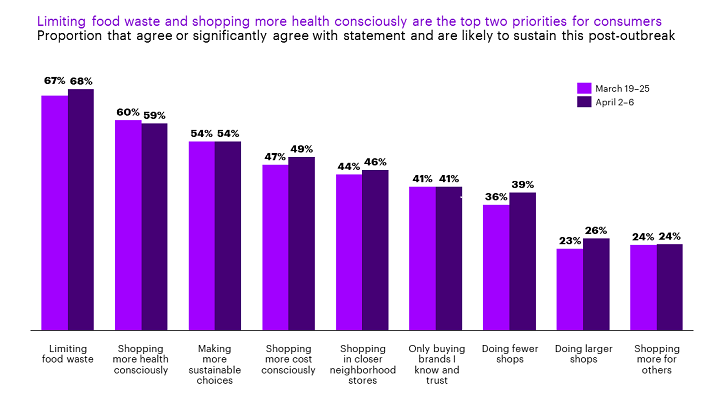

The outbreak of the Covid-19 not only changed the way people work and socialize but also the way they shop. During the initial stages of the pandemic, we were faced with an acute shortage of some commodities like maize meal, which greatly affected consumption patterns. The closure of some shops and major stores in March 2020 affected us, forcing us to only purchase essential items. Although the retailers and shops opened, later on, the behavior to purchase only essential commodities has not changed (Drury et al., 2021). In fact, the behavior has persisted throughout the pandemic period. Online shopping also emerged as people began working from home. More than ever before, shoppers began placing orders online, particularly for non-food items amid restrictions on movement.

Fear of infection for self, family, and friends has fuelled a change in behavior patterns. In my household, for example, behaviors such as cooking, baking, and consuming foods and drinks at home increased during the pandemic and are likely to remain post-pandemic. In addition, I have cut on behaviors such as visiting bars and restaurants frequently, due to loss of income and factors such as fear of infection (Drury et al., 2021). More importantly, I have acknowledged that investing for the future and diversifying investments can help me to meet my future financial goals. Relying on one stream of income has proved to be too risky and should be avoided by all means possible. Improving my nutrition and fitness level is a great lesson that I learned during the pandemic period. More than ever before, I am focused on improving my immune system and that of my family members to avoid infectious conditions such as the Covid-19 as related conditions like high blood pressure, diabetes, and heart diseases. Thus, the pandemic has completely altered my behavioral patterns and those of my household in response to the impacts of the pandemic such as declining income, restricted movements, and fear of infections.

Figure 2 shows behavioral change patterns during the pandemic. Source (Drury et al., 2021)

Conclusion

Overall, the Covid-19 pandemic completely altered my life. From working from home to loss of income, loss of loved ones, high cost of living, restricted movements, and limited access to nutritious foods. Further to this, the pandemic lead to a significant change in behavior patterns in response to the fear of infection for self and family members, as well as reduced income. Whether it is the way of living, working, or learning, the pandemic altered all aspects of my life. Although the world is headed towards recovery after massive vaccinations, certain behaviors are likely to remain even post-pandemic period. The bottom line is that Covid-19 has taught us invaluable such as better financial management, limiting wastage, the importance of multiple income streams, shopping more consciously, taking health with a lot of seriousness, and much more.

References

Buheji, M., & Ahmed, D. (2020). Covid-19 The untapped solutions. Westwood Books Publishing, LLC.

Cortes, G. M., & Forsythe, E. (2020). The heterogeneous labor market impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic. Available at SSRN 3634715.

Drury, J., Carter, H., Ntontis, E., & Guven, S. T. (2021). Public behaviour in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: understanding the role of group processes. BJPsych open, 7(1).

Green, N., Tappin, D., & Bentley, T. (2020). Working from home before, during and after the Covid-19 pandemic: Implications for workers and organisations. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 45(2), 5-16.

Hoffman, J. A., & Miller, E. A. (2020). Addressing the consequences of school closure due to COVID‐19 on children’s physical and mental well‐being. World medical & health policy, 12(3), 300-310.

Horton, R. (2021). The COVID-19 catastrophe: What’s gone wrong and how to stop it happening again. John Wiley & Sons.

Kenny, C. (2021). The Plague Cycle: The Unending War Between Humanity and Infectious Disease. Simon and Schuster.

MacKenzie, D. (2020). Stopping the Next Pandemic: The Pandemic that Never Should Have Happened, and How to Stop the Next One. Hachette UK.

Panchal, N., Kamal, R., Orgera, K., Cox, C., Garfield, R., Hamel, L., & Chidambaram, P. (2020). The implications of COVID-19 for mental health and substance use. Kaiser family foundation, 21.

Stephens, E. C., Martin, G., van Wijk, M., Timsina, J., & Snow, V. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on agricultural and food systems worldwide and on progress to the sustainable development goals. Agricultural Systems, 183, 102873.

Voigt, M. (2021). The Rise and Fall of Kenyan Entrepreneurs: Social Mobility in Kisumu (Vol. 11). Nomos Verlag.

write

write