Introduction

The utility of the prospects of lifestyle-based health promotion initiatives remains a phenomenology that is impacted by the adherence to the prescribed changes in behavior. However, the poor commitment to the prescribed behavioral changes recommended within a lifestyle intervention remains widespread over the long run, making the achievement of wellness a significant challenge (Mori, 2018). As presented in the literature, this explains the rationale behind the rise in chronic conditions that include cardiovascular diseases (CVD) such as cancers, respiratory infections, and diabetes that accounts for close to 59% of a pool of close to 57 million reported deaths annually and another global burden of disease that stands at 46%. As such, several lifestyle factors are considered significant in affecting the morbidity and mortality rates in several industrialized economies (Lathief & Inzucchi, 2016). As provided by the World Health Organization (2018), data reveals that the European region susceptible to hypertension, non-insulin-dependent diabetes, and cardiovascular conditions due to the lack of appropriate physical activities. The conditions account for over 600,000 of the recorded deaths within the region on an annual basis. Similarly, obesity and overweight issues are other risk factors associated with conditions such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and specified types of cancers that affect 30 to 80% of the adults in these countries (Lathief & Inzucchi, 2016). This suggests the need for behavioral modification interventions in assisting individuals in improving and avoiding their unhealthy behaviors, serving as the reason for the selection of Pender’s health promotion model. Therefore, there is a need to highlight how Pender’s health promotion model may serve as a tool used by nurses in planning for behavioral modification measures and interventions that may assist in the prevention of unhealthy behaviors.

Pender’s Health Promotion Model

Pender’s health promotion model holds that individuals, as seen in the context of those with chronic conditions that include cardiovascular diseases (CVD), cancers, respiratory infections, and diabetes, have unique personal experiences and characteristics that may influence and affect their subsequent actions (Sevinç, 2016). A set of these variables inform their behavioral knowledge. This remains a factor that has a more substantial motivational effect and significance and can be modified by considering nursing actions. Moshki et al. (2020) establish that health-promoting behaviors remain the desired outcomes and the endpoint of the health promotion model. In this regard, it is arguable that health-promoting behaviors are focused on improving health, bettering the quality of life, and enhancing the functional ability of people in different stages (Moshki et al., 2020). The last behavioral demand revolves around the competing preferences and needs that derail the intended issues of health-promoting behaviors and actions.

Scope and Concept of the Model

Pender’s health promotion theory or model primarily defines health and its concept as a positive dynamic or state and not the absence of a health condition. As established by Alkhalaileh et al. (2011), Nola Pender’s Health Promotion theory was pioneered in 1982 before improving in 1996 and later in 2002. The idea is primarily used in education, in nursing research, and practice. On the other hand, the application of the nursing theory within the scope of the nursing issue raised in this case is informed by observations and research, a factor that accords nurses the capacity to improve the well-being, self-care, and positive health behaviors of different populations (Alkhalaileh et al., 2011). The concept of the Health Promotion Model as imbued in the prospects of Pender’s theory was equally designed as a complementary element to the models driven towards offering health protectionism. The model is designed to incorporate several behaviors posing the need to improve health and wellness within the lifespan of different populations of people. Its purpose is inspired by the need to enable nurses to know and understand the significant determinants and triggers of specific health behaviors. This factor acts as the foundation of behavioral counseling in promoting healthy lifestyles and well-being (Khoshnood et al., 2018). According to Chen & Hsieh (2021), the health promotion model as applied within this context may be designed and integrated to increase wellness among patients with chronic conditions that include cardiovascular diseases (CVD), cancers, respiratory infections, and diabetes levels of wellness through a description of the multi-dimensional nature of each client and how they interact with an environment in their pursuit for health and wellness.

Structure and the Unique Focus of the Model

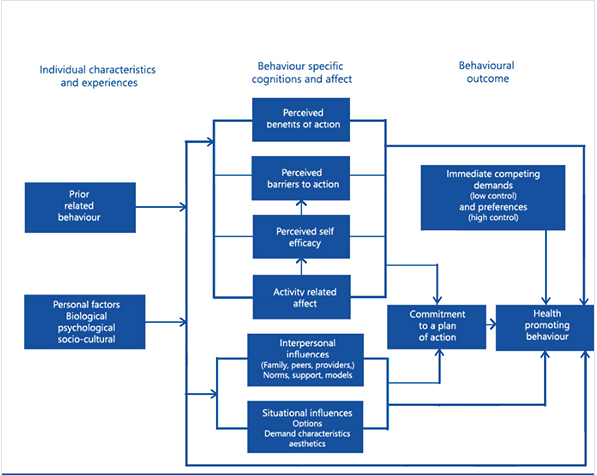

As provided in the structure in Figure 1 below, Pender’s Health Promotion model focuses on three fundamental areas: individual experiences and characteristics, behavioral and specific cognitive effects, and the behavioral outcomes of a process. The unique features and experiences revolve around the factors that help patients with chronic conditions that include cardiovascular diseases (CVD), cancers, respiratory infections, and diabetes to shape their actions. As seen in Pender’s theory, the past activities of these population groups directly connect with their engagement in health-supportive and promoting behaviors (Shahroodi et al., 2020). However, the personal attributes and the habits of these population groups may serve as a barrier to adopting health-promoting behaviors.

Figure 1: Structure of Pender’s Health Promotion model

The second element in the model’s structures primarily involves the aspect of behavior-specific cognitions that mainly have a significant and direct impact on individual motivation to the prospects of change. As established in the context of this study, nursing interventions driven towards reinforcing the adoption of positive health behaviors may, in this case, be tailored to address positive change. The variables that may be used primarily include the practical barriers and benefits of positive actions, activity-related, and self-worth results. The third element encompasses a behavioral outcome (Seo & Kim, 2021). The beginning of the products commences when the patients suffering from chronic conditions that include cardiovascular diseases (CVD), cancers, respiratory infections, and diabetes commit to the necessary behavior change measures to make changes in their lives. The individuals at this phase require support, especially with the presenting barriers efforts intended to produce positive health-promoting behaviors (Seo & Kim, 2021). Given this, it is assumable that the rationale and unique goal of the health promotion model lies in the stimulation of behavioral change that may result in positive health results.

Implementation Plan

The unique rationale for the implementation of Pender’s Health Promotion Model in the management of patients with chronic conditions that include cardiovascular diseases (CVD), cancers, respiratory infections, and diabetes revolves around improving the health of the patients by enhancing their functional abilities while bettering the quality of their lives (Cangöl & Hotun Şahin, 2017). The achievement of this goal may be reached by considering the below-established steps.

Step 1: The Assessment Phase

The first step will revolve around the use of four surveys or questionnaires that will require the patients to fill and complete duly for a better understanding of their knowledge on chronic conditions that include cardiovascular diseases (CVD), cancers, respiratory conditions infections, their attitudes towards the needs and the healthcare professionals, and the lifestyle factors that may contribute to the conditions. The surveys will primarily involve the patient attitude survey, patient chronic conditions knowledge questionnaire, health belief questionnaire, and lifestyle survey (Cangöl & Hotun Şahin, 2017). The study outcomes will provide a grounded understanding of the factors to consider in introducing the patients to the change process.

Step 2: Education and the Barriers to Change

An assessment of these factors will provide the health care providers with the knowledge required in educating patients. The patients will be equipped with the necessary knowledge regarding the condition, making informed and calculated choices by setting goals on their health outcomes. The education process will play a fundamental role in increasing these patients’ autonomy (Sabooteh et al., 2021). As stated in Pender’s theory, perceived barriers may constrain the patient’s commitment to these actions . A perceived barrier phenomenon may deny the patient’s responsibility to these actions , a phenomenon shown in the surveys. Pender’s model supports the achievement of self-actualization primarily through behavioral modification and the adoption of the best healthy lifestyle choices. Therefore, the model’s success is contingent on the fulfillment of the stability and basic needs of the patients. One of the barriers that are likely to alter the outcomes of the process revolves around the socio-cultural, biological, and psychological factors (Sabooteh et al., 2021). Secondly, patients with unstable living conditions due to the lack of fundamental needs such as limited mobility and scarce financial resources may further offer a challenge in implementing this model. This factor requires additional attention in the adoption of primary health behaviors.

Step 3: Goals and Plan of Action

In this phase, propositions from the model that focus on the patients’ commitment to engaging in behaviors that may be used in driving valued benefits may be considered. The focus on the nurses and caregivers will be on reinforcing the essence of pairing individuals suffering from chronic conditions to develop a plan of care that will increase their autonomy and result in the best outcomes in adherence and compliance with the established measures (Sabooteh et al., 2021). As such, the goals of managing chronic conditions would consist of educating the patients on healthy eating habits, blood glucose control, engagement in physical activities, the maintenance of their health through regular checks, smoking and drinking cessation, vaccinations, and meeting in support groups.

Step 4: Follow-up

As presented in this study, the rise in chronic conditions account for close to 59% of approximately 57 million reported deaths annually. Another global burden of disease (which disease) stands at 46%. Per se, the implementation of Pender’s theory will play a fundamental role in remedying these conditions among patients who choose change as a path to forge positive health outcomes (Shahroodi et al., 2020). Therefore, follow-ups will play a fundamental role in the management of the patients, an aspect that will aid in assessing their goals and some of the impeding factors that need to be addressed or revised to achieve the best outcomes.

Conclusion

As evident in the findings of this study, lifestyle-based health promotion initiatives remain a phenomenology that is impacted by the adherence to the prescribed changes in behavior. However, the poor commitment to the prescribed behavioral changes recommended within a lifestyle intervention remain widespread. As a result, the tendency makes it challenging to achieve wellness. Pender’s Health Promotion model focuses on three fundamental areas: individual experiences and characteristics, behavioral and specific cognitions and effects, and the behavioral outcomes of a process. Consequently, it is assumable that the rationale and unique goal of the health promotion model lies in the stimulation of behavioral change that may result in positive health results.

References

Alkhalaileh, M. A., Bani Khaled, M. H., & Baker, O. G. (2011). Pender’s Health Promotion Model: An Integrative Literature Review. Middle East Journal of Nursing, 5(5), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.5742/mejn.2011.55104

Cangöl, E., & Hotun Şahin, N. (2017). A Model of Breastfeeding Support: Motivational Interviews Based On Pender’s Health Promotion Model. Hemşirelikte Eğitim ve Araştırma Dergisi. https://doi.org/10.5222/head.2017.098

Cangöl, E., & Hotun Şahin, N. (2017). A Model of Breastfeeding Support: Motivational Interviews Based On Pender’s Health Promotion Model. Hemşirelikte Eğitim ve Araştırma Dergisi. https://doi.org/10.5222/head.2017.098

Chen, H.-H., & Hsieh, P.-L. (2021). Applying the Pender’s Health Promotion Model to Identify the Factors Related to Older Adults’ Participation in Community-Based Health Promotion Activities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 9985. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18199985

Khoshnood, Z., Rayyani, M., & Tirgari, B. (2018). Theory analysis for Pender’s health promotion model (HPM) by Barnum’s criteria: a critical perspective. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2017-0160

Lathief, S., & Inzucchi, S. E. (2016). Approach to diabetes management in patients with CVD. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine, 26(2), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2015.05.005

Mori, K. (2018). Promotion and Challenge of Health and Productivity Management Initiatives. Health Evaluation and Promotion, 45(2), 331–335. https://doi.org/10.7143/jhep.45.331

Moshki, M., Mohammadipour, F., Gholami, M., Heydari, F., & Bayat, M. (2020). The evaluation of an educational intervention based on Pender’s health promotion model for patients with myocardial infarction. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14635240.2020.1816487

Sabooteh, S., Feizi, A., Shekarchizadeh, P., Shahnazi, H., & Mostafavi, F. (2021). Designing and evaluating E-health educational intervention on students’ physical activity: Pender’s health promotion model application. BMC Public Health, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10641-y

Seo, J. H., & Kim, H. K. (2021). Factors affecting the health-promoting behaviors of office male workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Using Pender’s health promotion model. The Journal of Korean Academic Society of Nursing Education, 27(4), 412–422. https://doi.org/10.5977/jkasne.2021.27.4.412

Sevinç, S. (2016). Lifestyle Modification in Individuals with Myocardial Infarction: Pender’s Health Promotion Model. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 7(14), 147–152. https://doi.org/10.5543/khd.2016.93064

Shahroodi, M. V., Sany, S. B. T., Khaboshan, Z. H., Orooji, A., Esmaeily, H., Ferns, G., & Tajfard, M. (2020). Psychosocial Determinants of Changes in Dietary Behaviors Among Iranian Women: An Application of the Pender’s Health Promotion Model. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 0272684X2097682. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272684×20976825

write

write