Introduction

Female identity within the realm of modern and contemporary art has been a longstanding, multifaceted issue that pushes the boundaries of existing aesthetics and entrenched views of society. This study makes an extensive examination of the ways in which female artists from the modern and post-modern periods have both subverted and transformed notions of femininity as an object. This study will examine the various artistic approaches taken by these artists to question, subvert, and redefine the representations of women in art through a close examination of three particular pieces of art: “The Bath” painting by Mary Cassatt (1893), “Maman” sculpture by Louise Bourgeois (1999), and “The Dinner Party” installation by Judy Chicago (1974 – 79). Using an approach informed by feminist art history, this study attempts to unravel the complexities of female identity within this artist’s context. It offers perspectives on how their creations continue to shape the ever-evolving characterizations and conceptualizations of womanhood within the art sphere. In this regard, we shall discuss art’s female space and recreate a story about femininity, agency, and sociality using artworks and female space stories.

Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party” (1974-79)

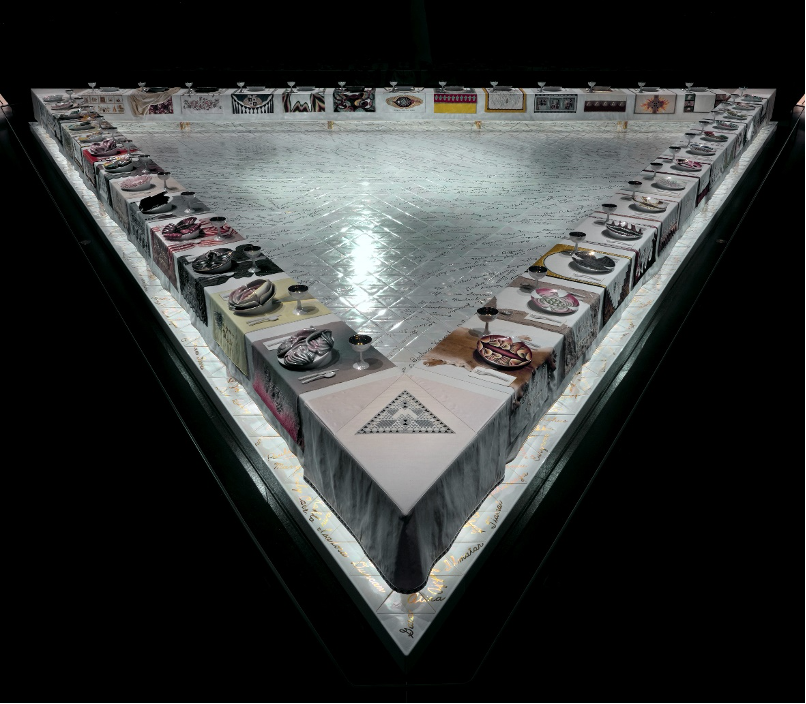

Judy Chicago’s masterwork “The Dinner Party” utilizes broadly interpreted symbols for a multifaceted definition of female identity and the reimaging of history as it relates to women who have been ignored and eliminated.” Placed within the walls of the museum is an abstract triangular table set up on which there are elaborate placements for these thirty-nine mythical and historical women. The design for each place setting is carefully made to describe what each woman stands out for or has accomplished.

It is deliberate that they used a triangle as Chicago’s shape, representing equal ladies. This geometrical orientation of diverse histories highlights how they are linked rather than presenting a collectivist history that opposes dominant linear male-focused historiography. Ornate place settings are a symbolic statement that illustrates the unique stories behind every woman, each represented by beautifully embroidered runners and fragile pottery dishes.

One cannot speak of “The Dinner Party” without mentioning its audacity that not only covers the ancient deities such as Kali and Ishtar but also the more contemporary heroes like Virginia Woolf and Georgia O’Keeffe. Chicago’s extensive investigation, as well as being detailed in presenting different kinds of women from varying cultures, has also been used to show that they tried to fight the marginalization of women that are often excluded from such accounts.

Chicago’s work is significant in the larger context of installation art, and Claire Bishop’s observations from “Installation Art: “A Critical History” provides a basis for understanding this significance in theory. Bishop argues that “The Dinner Party” is a one-way installation art that reconfigures traditional narrations by assigning female figures in history with a physical space again[1]. Through purposeful destabilizing the hierarchy of the gallery, Chicago adopts a feminist position toward the representation of history.

“The Dinner Party” also begins an essential discussion about what it means to be a female author in a metropolis like Chicago. The collaborative nature of the project undermined the notion that it was a work done single-handedly by a “lone” masculine genius artist since it required over 400 volunteers to build up the intricate table settings. Indeed, Chicago intentionally employed teamwork as a tactic for feminism where group effort is emphasized, denying the mythical notion of the sole creative spirit that has so long excluded women from the discourse about art.

However, The Dinner Party, as a work of visual art, remains a strong declaration of women’s being in history and skill beyond their being physically present. Through meticulous research, group constructivism, and strategic layout spatiality, Chicago reshapes historical representations of women’s identities by subverting their traditional depiction. Besides that, this piece forces audiences to reconsider conventional accounts of history and to raise more general questions as to how art could affect on social and cultural change[2].

Mary Cassatt’s “The Bath” (1893)

The famous painting of Mary Cassatt entitled “The Bath”, hosted at the Art Institute of Chicago, is one such instance challenging the stereotypes of women and motherhood in the late 19th century. The influence of an American impressionist painter, Mary Cossat, on the depiction of womanhood and “The Bath” is a manifestation of her commitment towards revealing the complexity of female personality.

The picture is in stark contrast to the usual idealized and often sexualized representation of women, which was standard at the time. It portrays a tender moment shared by a mother and her daughter in the process of their morning cleaning routine. Therefore, using Cassatt’s works, it would be possible to say that by putting emphasis on the parental function, she deconstructs female stereotypes and creates a more authentic and understandable vision of female identity.

Cassatt’s “The Bath” exemplifies her peculiar Impressionist approach that comprises of loose brushes and capturing the transient traits of color and light. It stresses the proximity and tenderness in the nature of the mother-child relationship, thereby increasing the emotional intensity of the scene. This makes her choice of subjects a deliberate attempt to move against conventional representations that limit women’s roles in life as well as art.

The book “Modern Art, 1851-1929: The article by Brettell entitled “Capitalism and Representation” serves as a historical background on Cassatt’s paintings under the social influence of the late nineteenth century[3]. When women’s roles began changing in society, women like Cassatt’s portrayed a picture of a mother engaging in a loving action. It would be possible to construe the painting as an expression of emerging views on motherhood and the acknowledgment that motherhood deserved attention in art.

Likewise, “The Bath” by Cassatt is, among other things, a critique of social conventions and reflects the new trend within Impressionism to depict everyday life rather than exceptional situations, events, or themes. By choosing ordinary events instead of traditional or mythical subjects, she defies the order in which history and art have always been conceived, thus raising the mundane to the level of skill. This democratization of subject matter is inherently feminist since, in itself, it expands what can be deemed meaningful in art[4].

Lastly, Mary Cassatt’s “The Bath” shows how much she has focused on presenting relatable and down-to-earth images about a woman. Her Impressionist style and the subject of womanhood helps question societal norms while adding to a larger conversation on how woman is portrayed within art. From the viewpoint of late 19th-century art, “The Bath” is an innovative picture that extends the narrative of femininity while functioning as a festivity of motherhood.

Louise Bourgeois’ “Maman” (1999)

A famous contemporary artist, Louise Bourgeois, impressed us with one of her landmark pieces, the Maman spider sculpture made of steel and marble from the Tate collections. It is one if not the most prominent symbol of motherhood: the immense size makes mothers appear protective and robust, while also challenging the common belief that spiders are dangerous and frightening.

“Maman” shatters people’s preconceptions of things like power, beauty, and motherhood. Spiders being always known as creatures associated with danger are represented in an enormously giant arachnid standing far above thirty feet and which attracts attention. Moreover, this gives the piece even more levels of meaning since the material is chosen with care. The difference between the warm, organic marble and the cold, industrial steel emphasizes a complexity within a female nature and multiple maternal moods.

The spider in the hands of Bourgeois metamorphosed into an arthropod with a reputation for crafting elaborate webs. Slowly, it begins to mean love, care, and artistry. Specifically, Bourgeois herself has spoken about the symbolic connection of spider-as-mother and related it to her role both as an infant caregiver and mother. “Maman” defies prejudices regarding women by metamorphosing the disturbing picture of a spider into a forceful allegory for protection.

The book “From Margin to Center: With reference to Julie H. Reiss’s “The Spaces of Installation Art” provides a valuable critique of how Bourgeois’ sculpture and assemblages have influenced contemporary installation art. Reiss researches the phenomenology or spatial dynamics of installation art, where he tries to comprehend space in relation to work as an object[5]. The size, positioning, and context of “Maman” in the museum make her an integral part of the space where she acts as a catalyst for visceral and emotional interaction between the audience and the work of art. The selection of Tate as a venue for the exhibition adds spice to the spatial debate since it contributes significantly to the story around the artwork.

“Maman” was part of Bourgeois’ oeuvre on motherhood, gender, and the human condition. Bourgeois uses a spider as a recurrent motif to transform it from something intimidating to comforting. These maternal overtones are then further strengthened through the choice of title which is “Maman” which means Mother in French.

This body of work confronts convention and deepens debate on the notion of women as caregivers. “Maman” indeed shows Bourgeois’ mastery at bestowing depth of meaning to ordinary objects; it is a piece that extends beyond its literal appearance into a contemplation zone, encouraging viewers to question the familiar notions of female hood, power, and love[6].

Overall, Louise Bourgeois’s “Maman” is extensive research into woman identity that challenges conventional ideas about motherhood and offers multiple vantage points for understanding this paradigm. The installation’s subject matter, material, and spatial dynamics all urge the viewer into a deep-meaning conversation on women, caregiving, and the creative transcendence of the artwork itself.

Conclusion

In summary, the artistic works by Judy Chicago, Mary Cassat, and Louise Bourgeois show that any art has the power to subvert and challenge ideas about women’s identity in relation to modern and post-modern art. Through their various perceptions including those of “The Dinner Party,” “The Bath,” and “Maman”, these artists have moved beyond the conventional views of art by creating diverse narratives that challenge societal norms placing women above men, discuss ideas surrounding feminity, agency and recognize history. As a whole, the enormous joint of Judy Chicago’s installation questions for historical eradication; an individual portrait of Mary Cassatt towards defining motherhood; and, finally, the powerful spider creation by Louise Bourgeois that subdues stigmas, continues growing the feminist artwork The roles of female works as a changer agent encourage the viewers to question and reconstruct the social constructions that have shaped notions of women in art and society generally and female identity which is multifaceted and complicated in its essence. This discourse by these artists makes us acknowledge the effects of art on smashing stereotypes, extending representations, and creating a fairer conception of female identity that will endure through time.

Bibliography

Bishop, Claire. Artificial hells: Participatory art and the politics of spectatorship. Verso books, 2023.

Brettell, Richard R. Modern art, 1851-1929: capitalism and representation. Oxford University Press, USA, 1999.

Nochlin, Linda. Women, art, and power and other essays. Routledge, 2018.

Perry, Gillian. Gender and art. Yale University Press, 1999.

Pollock, Griselda. “Firing the canon.” Differencing the canon: Feminist desire and the writing of art’s histories. New York: London: Routledge (1999).

Reiss, Julie H. From margin to center: The spaces of installation art. mit Press, 2001.

[1] Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (Verso Books, 2023).

[2] Gillian Perry, Gender and Art (Yale University Press, 1999).

[3] Richard R. Brettell, Modern Art, 1851-1929: Capitalism and Representation (Oxford University Press, USA, 1999).

[4] Griselda Pollock, “Firing the Canon,” in Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art’s Histories (New York: London: Routledge, 1999), 9-36.

[5] Julie H. Reiss, From Margin to Center: The Spaces of Installation Art (MIT Press, 2001).

[6] Linda Nochlin, Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays (Routledge, 2018).

write

write