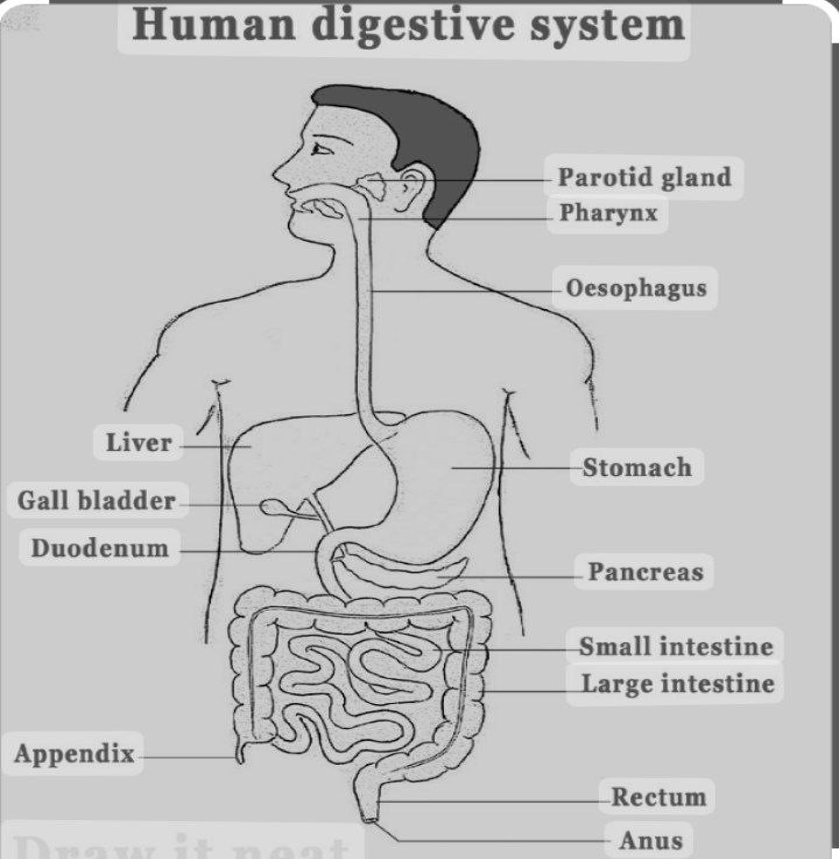

The digestive system consists of the GI tract and other organs responsible for breaking down food. The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is a network of hollow organs that begins at the mouth and terminates in the genitalia. The digestive system consists of the oral cavity, the esophagus, the stomach, the proximal and distal intestines, and the anus, the end of the large intestine—the authors (Babkin et al., p. 368). Digestion is the process of breaking down food into smaller and smaller particles. The nutrients in food can’t be utilized adequately unless this occurs. First, let’s have a look at the anatomy and physiology of both the human digestive system and the Poultry digestive system, and then we’ll go through how they compare and contrast with one another in the context of this study.

The human digestive system

The digestive system breaks down food into usable forms, such as vitamins, minerals, and energy. When you empty your intestines, your organs of elimination separate and organize the waste. Nutrition from food and drink is crucial to maintaining good health and carrying out daily bodily functions. Thus digestion is an absolute must. In addition to water, nutrients include carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, vitamins, and minerals. Food and liquids are processed and absorbed by the digestive system to fuel the body, nurture growth, and repair damaged cells.

Digestive organs

The digestive tract consists of the oral cavity, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, rectum, and anus. (Code et al. Pg. 122) The gallbladder, liver, and pancreas aid this.

Each digestive system part communicates with the others:

Mouth

The oral cavity starts digestion. Digestion begins before you eat. Pasta and fresh bread smells might make your mouth water. You chew when you first begin eating to make your food easier to digest. Saliva mixes with food to make it digestible. The tongue carries food from the mouth to the esophagus.

Esophagus

The esophagus carries food from the mouth to the windpipe (windpipe). A flap called the epiglottis covers the windpipe to keep food and liquids from entering the trachea and causing choking (when food goes into your windpipe). Quick muscle contractions called peristalsis transport food from the esophagus to the stomach. When the lower esophageal sphincter relaxes, food can go from the stomach into the esophagus. When the sphincter tightens, food and liquids from the stomach cannot enter the esophagus. If it doesn’t, acid from the stomach can back up into the esophagus and cause painful symptoms like heartburn.

Stomach

Digestive enzymes are added to food in the stomach. It aids digestion. Enzymes transform food into fuel. To break down food, stomach cells release acid and enzymes. After digestion, stomach contents are transferred to the intestines.

The small intestine

Duodenum, jejunum, and ileum comprise the small intestine, a muscular tube measuring 22 feet in length. Nearly 22 feet is the estimated length of the small intestine. The gastrointestinal tract is in charge of breaking down food by employing pancreatic enzymes and liver bile. (Denbow et al. Pg. 367) Food is moved through the organ by peristalsis and mixed with digestive fluids made by the pancreas and the liver. The initial section of the small intestine (the duodenum) is responsible for breaking down food into its components. It is a crucial factor in the deterioration process. The jejunum and ileum, two sections of the lower intestine, are responsible for the vast bulk of the body’s nutrient absorption. The small intestine is responsible for turning only partially solid food into a liquid condition. Components such as fluid, bile, enzymes, and mucus all play a part in the textural change that can be observed. Following digestion, the contents of the small intestine are transported to the larger intestine, where they are reabsorbed as nutrients and expelled along with any liquid that may have been produced during the process (colon).

Pancreas

Enzymes produced by the pancreas into the duodenum help digestion of all three macronutrients: protein, fat, and carbohydrates. The pancreas is also responsible for the release of insulin into the bloodstream. Insulin, a hormone found in your body, is responsible for the majority of the metabolism of sugar.

Liver

The liver’s primary role in the digestive system is metabolizing the nutrients ingested by the small intestine. The small intestine relies on bile, a digestive fluid secreted by the liver. Bile is essential for breaking fat down and absorbing specific vitamins. Your liver can be thought of as the “factory” of your body’s chemistry. The liver processes the colon’s nutrients to produce various essential body compounds. The liver is also responsible for detoxifying toxins. It metabolizes and secretes a wide variety of potentially harmful substances.

Gallbladder

The gallbladder stores bile from the liver until it is needed to aid in the digestion of fats in the small intestine duodenum.

Colon

The waste is broken down in the colon; thus, passing feces is easy and painless. Approximately 6 feet in length, it connects the rectum to the small intestine and is lined with muscle. The cecum, the transverse colon, the descending colon, the sigmoid colon, and the rectum are the five parts of the colon.

With the help of peristalsis, the colon can transport liquid and solid feces. Stools lose fluid as they move through the colon. The sigmoid colon (S-shaped) stores waste until it is “massively moved” into the rectum once or twice daily. It typically takes the colon around 36 hours to process a bowel movement. Stool primarily consists of undigested food and microorganisms. Vitamin production, waste product and food particle processing, and defense against harmful bacteria are just a few of the many roles played by these “good” bacteria. When the descending colon is entire, stool or waste is passed through the rectum and out of the body (a bowel movement).

Rectum

Connecting the colon to the a.n.us is a straight tube called the rectum, about 8 inches long. The rectum takes in waste material from the colon, sends the signal for waste to be evacuated (pooped out), and stores waste material until it is discharged. Any time gas or stool enters the rectum; sensors send signals to the brain. The brain then has to decide if the genitourinary system can empty its bowels. When the sphincters relax, the rectum can contract and empty its contents. The sphincter constricts, and the rectum dilates to make place for the bowel contents if they cannot be released, providing momentary relief from the pain.

Anus

The anus is the digestive process’s last organ. Two anal sphincters and the pelvic floor muscles work together to create a 2-inch-long channel (internal and external). The lining of the anus, up top, can sense a person’s rectal contents. It reveals if the container contents are liquid, gas, or solid. It is the job of the sphincter muscles, which encircle the anus, to control bowel motions. To prevent involuntary diarrhea, the pelvic floor muscle tilts the pelvic organs. The internal sphincter is usually closed except during feces passage into the rectum. This prevents us from urinating or defecating on our own accord when we are asleep or otherwise unaware of feces, allowing us to remain continent. The external sphincter is responsible for holding in waste until a person reaches a toilet, at which point it relaxes, and debris can be eliminated.

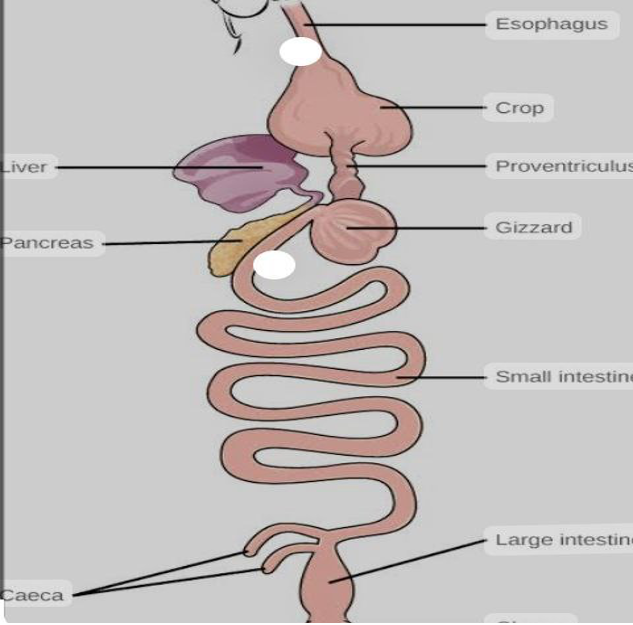

The Poultry digestive system

The beak eats broken or pelleted feed, small grains, grass, and insects. Chickens are omnivores and can consume meat (grubs, worms, and even the occasional mouse) and vegetables in addition to their commercial diet (grass, weeds, and other plants). Saliva and enzymes accompany food to the esophagus. (Hogben et al. 392) The crop, an elastic pouch at the chicken’s neck, stores food after it passes past the esophagus. The bird’s stomach (proventricular or gizzard) grinds the food as it passes down the crop.

Gizzards allow chickens to survive without teeth. The muscular stomach pylorus uses grit to break down grain and fiber into smaller, more digestible bits (tiny, hard particles of pebbles or sand). The small intestine absorbs nutrients after the gizzard processes food. Microorganisms digest the leftovers in the ceca, a blind sack in the lower intestine. The large intestine eliminates moisture from hard-to-digest foods after food passes through the ceca. Chicken droppings’ white urine comes from the cloaca. Gases and solids escape the chicken through the cloaca vent.

The similarities and differences between the digestive systems of humans and a typical domestic bird (fowl)

Differences

Some distinctions can be made between the digestive systems of humans and farmed fowl. The digestive process begins in the stomach, which breaks down food and absorbs nutrients. The stomach is the first organ involved in digestion. Large intestines are responsible for absorbing the water that comes from digested nutrients. The lymphatic system is then responsible for transporting the nutrients to the bloodstream.

In contrast to humans, fowl and poultry do not possess teeth; hence, they do not engage in chewing food. They swallow their meal without chewing it in one swift motion instead.

Humans’ digestive systems are quite different from those of birds. In comparison to birds, humans can eat significantly more due to our more extensive and more complex digestive systems. A bird’s digestive system is much less complex and contains fewer parts than a mammal or even a reptile. Reptiles and mammals have livers, but the human biliary system (including the liver) is superior because it filters harmful substances out of the body via urine and bile.

The digestive systems of birds and humans are very different from one another. Acid is produced in the human stomach, in contrast to the gastric secretions found in the guts of birds. The human colon is divided into three separate sections: the rectum, the sigmoid colon, and the ascending colon. The anatomy of a chicken consists of the anus, ventriculus caecum (also known as the coccygeal gland), the cecum, and the large intestine.

Domestic fowl have a digestive system that is very different from our own. Crop, chromocyte, and caeca (the first part of the small intestine) make up the crop. (Turk et al. Pg. 1230) Crop storage allows for a bolus of food to be swallowed and absorbed into the body rather than smaller, more frequent meals. The epiglottis, sometimes known as the “backbone,” connects the two ends of the esophagus and keeps food from going down the wrong tube (the trachea) (or trachea).

A domestic fowl’s digestive tract is very different from that of humans. For example, a bird’s digestive system is considerably more condensed than ours and lacks both small and large intestines. Compared to ours, a bird’s digestive system is also significantly shorter. Even more so than humans, birds lack a stomach since they rely almost exclusively on a diet of seeds and insects. This makes it even more difficult for birds to digest food.

Similarities

The digestive systems of humans and birds are very comparable in terms of their roles in the gastrointestinal system. Despite its relatively small size, this body region houses several organs involved in digestion. (Ziswiler et al. Pg. 347) A bird’s stomach does not contain any part of the digestive tract; instead, it has a specialized piece of its intestine known as a crop that it utilizes to store food and digest it while the bird is still alive. Although people consume a wide variety of meals, we need the capacity of birds to store significant quantities of food for extended periods. In the same way that animals use digestive fluids to break down the food they eat, human beings have their crops that do the same function.

Like farmed fowl, humans have a digestive mechanism that breaks down food gradually. There are several parallels between human digestion and bird digestion because of this commonality. First and foremost, stomachs are stomachs everywhere; they’re vital to the digestive process, and we can’t tell them apart. Its tissues then employ the enzymes in an animal’s stomach to manufacture proteins with a specific purpose, just as different tissues use human enzymes to synthesize proteins with other functions. Enzymes, present in both birds and humans, serve a wide variety of critical roles, including digestion, nutrition absorption, metabolism enhancement, and disease prevention and treatment.

The digestive system of humans is comparable to that of fowl kept as pets or for food production. They have something called a proventriculus, an extra digestive tract that acts as a supplementary conduit for the processing and absorption of food. Both animals have gastric pits, the openings through which digests are gathered and carried out of the body by caeca, which are small orifices.

Work Cited

Babkin, B. P. “The digestive work of the stomach.” Physiological Reviews 8.3 (1928): 365-392.

Code, Charles F. “The digestive system.” Annual review of physiology 15.1 (1953): 107-138.

Denbow, D. Michael. “Gastrointestinal anatomy and physiology.” Sturkie’s avian physiology. Academic Press, 2015. 337-366.

Hogben, C. ADRIAN M. “The alimentary tract.” Annual Review of Physiology 22.1 (1960): 381-406.

Turk, D. E. “The anatomy of the avian digestive tract as related to feed utilization.” Poultry Science 61.7 (1982): 1225-1244.

Ziswiler, Vinzenz, and Donald S. Farner. “Digestion and the digestive system.” Avian biology 2 (1972): 343-430.

write

write