Executive Summary

This article will explore the links between wildlife trafficking and various other problems, including the erosion of government reforms in marginalised areas, national and international security risks, and the involvement of non-state actors in supplying weapons during civil conflicts. The global fallout of this crime is the subject of this article. Poaching of endangered species like elephants and rhinoceroses has skyrocketed in recent years as demand rises worldwide. Reducing consumer demand for IWT products, building strong legal frameworks and deterrents, improving law enforcement, and developing sustainable livelihoods for individuals affected by IWT are only some topics covered in the paper. This research summarises the IWT supply chain model and investigates the circulation channels for illegally traded rhino horn and ivory. For instance, recent inquiries into IWT trafficking activities have revealed huge and intricate criminal supply networks for rhino horn and ivory involving several Asian states. Ivory and rhino horn are sometimes transported across borders using various cover stories. This paper delves into supply and demand, commerce, and amazing products. According to the findings, major illegal animal supply networks are based in Vietnam, Myanmar, and Thailand; nevertheless, these countries are mostly used as transit sites for items en route to China and Japan. There are seven concrete suggestions for ending wildlife trafficking in the report. Suppose performance goals are created, and adequate resources are allocated to inquiries, interrogations, and criminal charges related to wildlife trafficking. In that case, multi-agency approaches to combat illicit wildlife trade will increase.

1.0 Background Research

The worldwide reduction of animal populations is a major problem. This precipitous drop has led many to conclude that human biomass now far exceeds that of any other living thing. Ecosystem loss and the global illegal wildlife trade (IWT) killing of animals for their parts are two major contributors to this disaster. One of the most lucrative underground markets, the wildlife trade, is estimated to be worth between $7 and $23 billion annually (Sosnowski et al., 2019). Given this endeavour’s high earnings and low risks, more sophisticated, transnational, and well-organised criminal networks are drawn to it. When economies are bad, corrupt people are in charge, law enforcement is lax, and regional governments are unstable, poaching increases.

Despite the focus on elephants and rhinos, many other animal species are in peril. Non-human primates, including gigantic apes, monkeys, and pangolins (Schlossberg et al., 2020), are among the most endangered animals on the planet. Illegal trade and poaching pose serious threats to many animal and insect species. Products featuring animals are popular because consumers believe they will improve their health or social standing. Speculative purchasers interested in unusual animals, such as exotic pets, help support the market.

People and animals worldwide are at grave risk because of the IWT. Potential unintended consequences of IWT include cruelty to animals and biodiversity loss. Social and economic stability, cultural assets, the spread of zoonotic diseases and introduced species, and the loss of agricultural land are all at risk due to depleting natural capital (Phelps et al., 2018). IWT has harmed investment possibilities relating to environmental sustainability in several sectors, including corruption, financial fraud, political instability, and consolidation. Consequently, IWT is a roadblock to meeting the SDGs. These goals focus on enhancing the region’s safety, health, and wealth. Regarding reducing crime rates, the government recognises the importance of law enforcement (Sas-Rolfes et al., 2019). Research into techniques to bolster the scientific evidence against IWT should be a top priority for policymakers.

To halt the illegal traffic of rhino horns, the policy should work to decrease demand while increasing supply. A common argument made by those in favour of a “no rhino horn” policy is that the government should emphasise reducing demand (Margulies et al., 2019). Many believe that limiting the illegal trade of rhino horns can be accomplished by legalising the trade of rhino horns (Esmail et al., 2020). The legal trade in rhino horn might eventually wipe off the species if tastes do not shift.

The international trade in rhinoceros horns is illegal because both China and Myanmar are signatories to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. The “horns exhibition” (Cooney et al., 2016) of the corporation demonstrates that Mong La willfully disregards federal regulations that prevent it from operating. Since there is no Burmese presence in the area, researchers have recommended that Chinese authorities increase monitoring and prosecutions at the Mong La-Daluo border crossing to render it useless to traffickers (Milner-Gulland et al., 2018). For many years, TRAFFIC and WWF have worked together, with support from the governments of Myanmar and China and the CITES Secretariat, to combat wildlife trafficking along the Mong La-Dalou border. TRAFFIC’s focus on trade in strategic areas like Mong La (Biggs et al., 2016) may impact the media, governments, and sustainability groups.

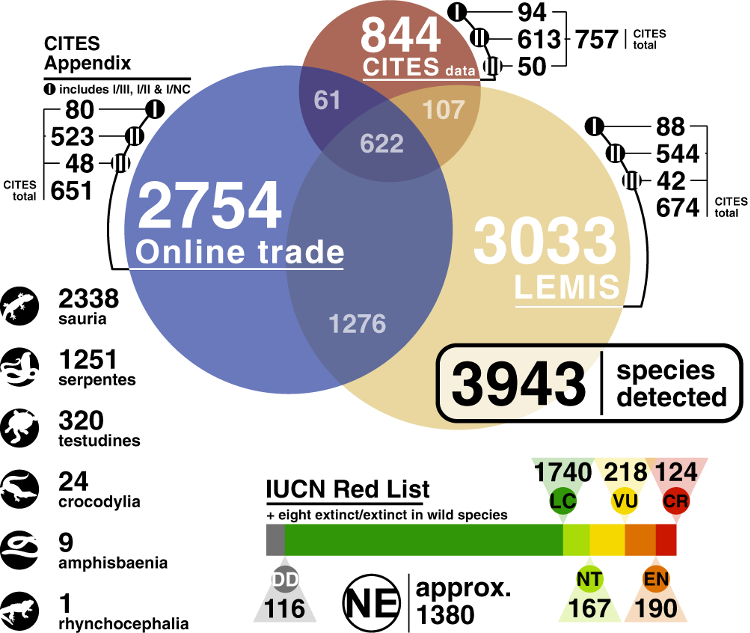

Biologists concerned with biodiversity preservation argue that revising existing global market predictions for animal commodities and services is necessary to lessen barbarism’s blow to the Tree of Life. Researchers still choose to study vertebrates over invertebrates and plants despite the lack of available data (Fukushima et al., 2020). We present a series of illustrations below to emphasise the gravity of IWT and its far-reaching effects on animal populations, biodiversity, ecosystems, economies, and communities. Therefore, groups working to end animal cruelty could take cues from the company’s marketing strategies (Phelps et al., 2018). Through this research, we hope to shed light on the problem, highlighting the pros and cons of generating and disseminating novel yet critically important ideas in the workplace.

The fundamental goal of this study is to broaden our understanding of the concepts underlying solution-oriented dialogue. In wildlife community policing, we evaluate the significance of studies that distinguish between user-generated material and substantive message content. We found educational links between content quality and social networking sites using an unsupervised compositional analysis. Finally, it provides recommendations for future studies and a discussion of the consequences of our findings (Esmail et al., 2020). In our last piece, we provided context and a comprehensive plan to end IWT, demonstrating how useful this can be in spreading the word about the hazards of the practice.

1.1 Themes and Concepts of IWT

The Illegal Wildlife Trade (IWT) is a multibillion-dollar clandestine economy threatening animals and humans. Ecosystems, economies, and local populations are perilous from the illegal wildlife trade (IWT). Understanding marketing principles could aid in preventing wildlife trafficking in several ways. This research aims to investigate the association between conservation appeal framing and participation in online communities. The United Kingdom provides funding for the IWT Challenge Fund, which works to stop poaching and preserve biodiversity.

Many animal and plant species are in danger due to the illegal wildlife trade. Prior attempts to criminalise the industry targeted unlawful activities, including hunting and growing plants (Verssimo & Glikman, 2020). Animals, plants, and their byproducts are being illegally traded across international borders, which is the root source of the issue. To meet the increasing demands of our customers, we must, therefore, expand our workforce. Official and unofficial groups alike have pledged to address this crisis head-on. Stakeholders must identify and implement the most effective strategic solutions if they wish to see a rapid shift in consumer demand and expenditure away from illicit wildlife items.

Figure: AI-based Strategic Marketing: SMAI Model

Legal frameworks forbidding particular behaviours and tying these limitations to stated aims and policy objectives can effectively combat the illegal wildlife trade by deterring it, apprehending those involved, and prosecuting it. Lawmakers should create a system that is easy to understand and implement. All public and private institutions and their employees should be monitored and regulated to uphold the abovementioned principles. Establishing and maintaining the framework’s processes and procedures is essential (Roe & Booker, 2019). The norms and legislation created by international treaties are binding on national legal systems.

Readers of IWT care deeply about enhancing police forces around the world. Arousal-based social and emotional appeals inspire audience participation by tapping into the depths of their emotions. Developing proficiency in various contexts can help one’s social, communicative, and integrative abilities. From the outside looking in, criminal activity and law enforcement appear to be positive value creators that elicit emotional appeals like anger (Cooney et al., 2016). These concepts are relevant to the most threatened species, as shown through a value feedback framework based on a particular approach.

Reserving natural resources and alleviating poverty are at the heart of the projects that get funding from the IWT Challenge Fund and the Darwin Initiative, respectively. Because of this, their actions contribute to several of the Sustainable Development Goals. In particular, Sustainable Development Goal 1 (to end poverty around the world), Sustainable Development Goal 15 (to learn how to manage forests sustainably, prevent soil erosion and destruction of wetlands, but rather halt biodiversity loss), Sustainable Development Goal 14 (to preserve and sustainable and responsible use of oceans, seas, but rather marine resources for future generations), and Sustainable Development Goal 6.6 (to protect biodiversity) all benefit significantly from the projects that both funds support.

It is a way of influencing people without interacting with the communicator or trying to figure out what they are experiencing or why. Although perception and comprehension appeals prioritise veracity and sound reasoning, sociocultural appeals prioritise education over amusement (Biggs et al., 2016). As a result, we focus on IWT’s results rather than its methods or the people, elephants, or rhinos who participated in it).

2.0 Mechanisms and Institutional Environments of IWT

2.1 IWT Supply Chains

The illegal wildlife trade threatens conservation efforts. Many other countries are involved in the production, distribution, and consumption stages of the international wildlife trade, but China is a crucial link in the chain. However, China’s animal conservation and use restrictions, especially those prohibiting wildlife use in medicines (Challender et al., 2018), impede its ability to monitor its illegal wildlife trade. Illegal wildlife trade across borders can be reduced with proper planning, coordinated regulatory surveillance, and cooperation with other supply-management nations.

Figure Actors along the value chain of rhino horn and ivory

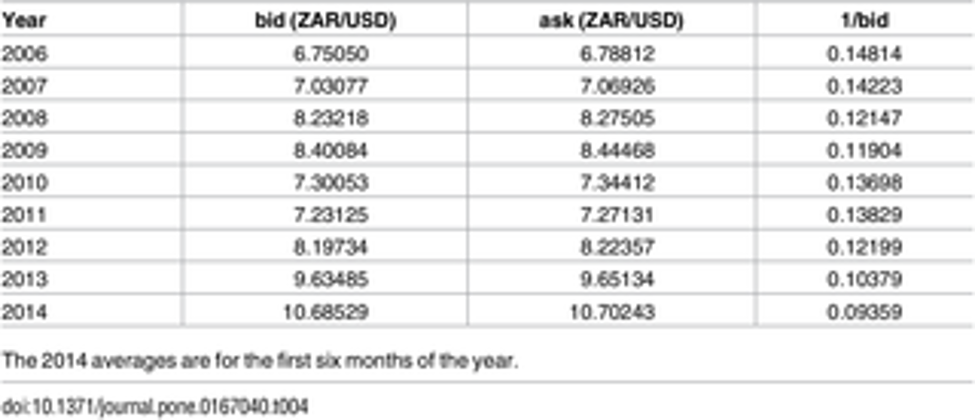

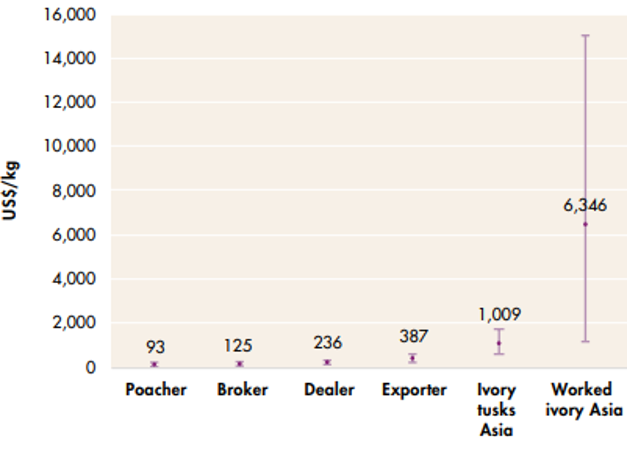

To properly assess risks in industries like wildlife trafficking, it is necessary to understand the full value chain (Challender et al., 2018). Total construction project value, illegal theme fueling income and wealth expansion, and quantity of specialists played significant roles in the investigation.

Acquiring ivory and rhino horn, manufacturing them commercially, smuggling people, and selling them to clients are all part of the illegal supply chain (Challender et al., 2018). Poached or illegally slaughtered animals are the primary ivory and rhino horn source in the black market. Thefts of stockpiles or deaths due to natural causes also contribute (though negligibly) to the total. The tusks and horns of poached animals are traded for money (Baker, 2018). Smaller stores receive or buy these goods for preparation for larger national or regional shipments.

Recent investigations into the illegal supply networks for rhino horn and ivory have revealed that these networks are sophisticated and pervasive throughout multiple Asian countries. Ivory and rhino horn are sometimes transported across international borders using various cover stories. Ivory and rhino horns are frequently smuggled into Asia. Symes et al. (2018) note their importance in the trade of rhino horns to Asian markets. Migrant smuggling gangs are a crucial cog in the criminal economy’s supply chain because of the high profits they may generate. Everyone in the economic system must be educated, from the poacher to the consumer. Countries involved in the illegal trafficking of rhino horns and ivory should draw policy lessons from the need to get new products to market as quickly as possible (Symes et al., 2018).

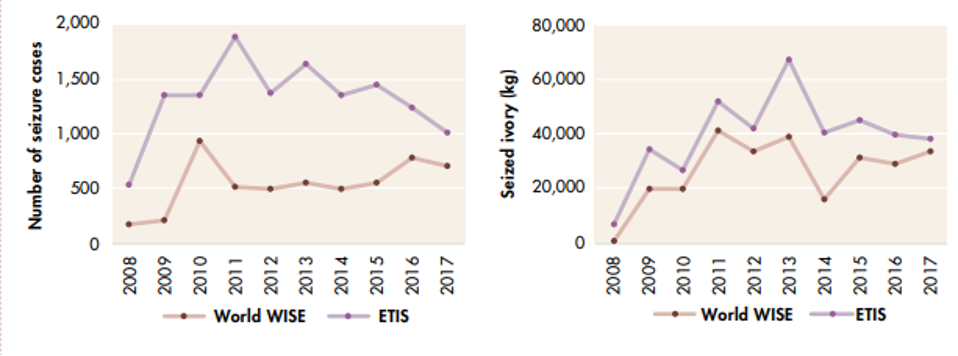

Figure: Comparison between ETIS and World WISE ivory seizure data, 2008 – 2017

Those involved in the illegal ivory and rhino horn trade rely heavily on the money they make from these activities. Most ivory and rhino horn on the black market comes from recent deaths. Factors like high intrinsic mortality and traffic offences contribute marginally to the whole. Therefore, poaching is a fundamental problem. The animals are slaughtered for their tusks or horns, which are stolen and sold. Therefore, the owners of Chinese companies can profit from consolidating smaller shipments into larger ones for distribution throughout China and the neighbouring territories (Baker, 2018). The Asian market is flooded with illegal goods shipped by numerous individuals and companies.

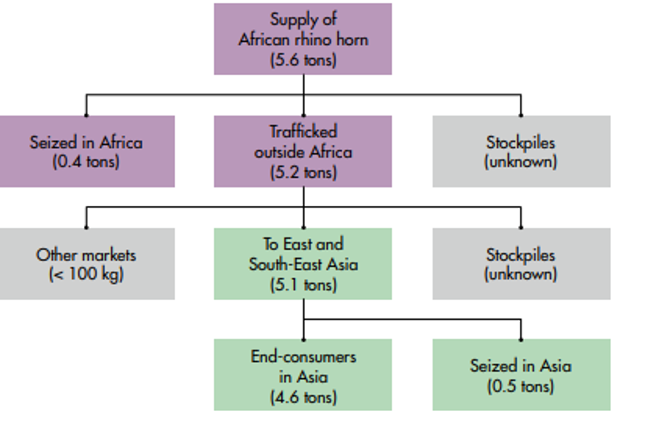

Figure: Combating Rhino Horn Trafficking: The Need to Disrupt Criminal Networks

The six evocative levels of the black market trade system are the poachers, brokers, channel partners, exporters, distributors, and market makers. However, the rhino horn trade is different from the ivory trade. Certain aspects of the underground supply chain can be relied upon without fail. Levels are unknown, as is their makeup (McNamara et al., 2016). A solid education is the best way to learn about underground marketplaces, even though certain products must be screened again before they reach the consumer.

Poachers can be broken down into three groups based on their skill level. Poachers that kill animals for no other reason than subsistence or ceremonial use are often motivated by a desire to provide for their families. Due to their occasional hunts and lack of access to high-tech weapons like tranquiliser guns and machine pistols, these bands of poachers could benefit from greater coordination (Biggs et al., 2021). Poachers are frequently people experiencing poverty who are willing to risk their situation to get a few extra dollars.

However, the members of an elite poaching squad will be in the excellent physical condition and more than capable of using such weapons. Killing rhinos for their horns is a prime example of this problem. Military personnel, law enforcement officers, tournament scouts, and others who have received specialised training in real-time surveillance or shooting bolster the assertion (McNamara et al., 2016). Poachers with ties to criminal organisations may request and receive full payment for their items before they are even sent.

Figure: Flows of rhino horn, annual estimates based on 2016-2018 data

Brokers are third-party intermediaries who mediate business deals. These middlemen are easy to track down since they typically set up shops close to illegal hunting grounds, making them visible to campaigners and potential customers. Poachers and those who buy illegally taken animal products are not always the same persons (Roe, 2018). The highest-ranking traffickers are trying to separate themselves from poaching. In the human trafficking industry, intermediaries and runners are more common than actual poachers.

Most brokers and distributors operate from a single major city serving the entire country. In preparation for future sales in foreign markets, they amass supplies. In order to manage the delivery of goods, shipping companies and regional/international wholesalers rely on credit intermediates (Fukushima et al., 2020). The majority of mediators for Asian nations are also from Asia.

Poaching, stealing from public or private stocks, and forged hunting licenses are all possible ways to obtain rhino horn illegally. Any of these acquisition forms are vulnerable to corruption (McDonald, 2016). It is possible, for instance, to pay storage managers to gain access to the horns the government has confiscated. The few surviving rhinos are dispersed across vast conservation zones. People are encouraged to report any suspicious activity in remote areas. In order to gain access to rhino habitats and information on where rhinos are hiding from poachers, bribery and other forms of coercion may be used (Moneron et al., 2019).

Figure: Variation of ivory price data by trade level, multi-year average, 2014-2018.

The search for new employees or transportation services could be conducted regionally, nationally, or internationally. It makes determining appropriate punishments for specific offenders more difficult. Corruption may arise from the transportation of rhino horns via government vehicles. Even though worldwide and national sanctions exist on the rhino horn trading, bribery is still commonly used in the promotion, sales, and delivery of the product (Hauenstein et al., 2019). In the business world, “protective immunity” could be useful for dealers with good rapport with law enforcement. Bribery of municipal and provincial officials is common practice for business owners seeking to “buy” or “avoid” warning of police inspections.

2.2 Supply – trends, trade patterns, and characteristics.

There is a sizable market for animal-based goods. The illegal trade in wildlife is reportedly the third largest in the world after drugs and firearms. The annual worth of wildlife trafficking is estimated to be $10 billion, according to the US Department of State (Roe, 2018). The illegal wildlife trade has repercussions everywhere. It is a network of countries and regions that spans the globe and includes all continents.

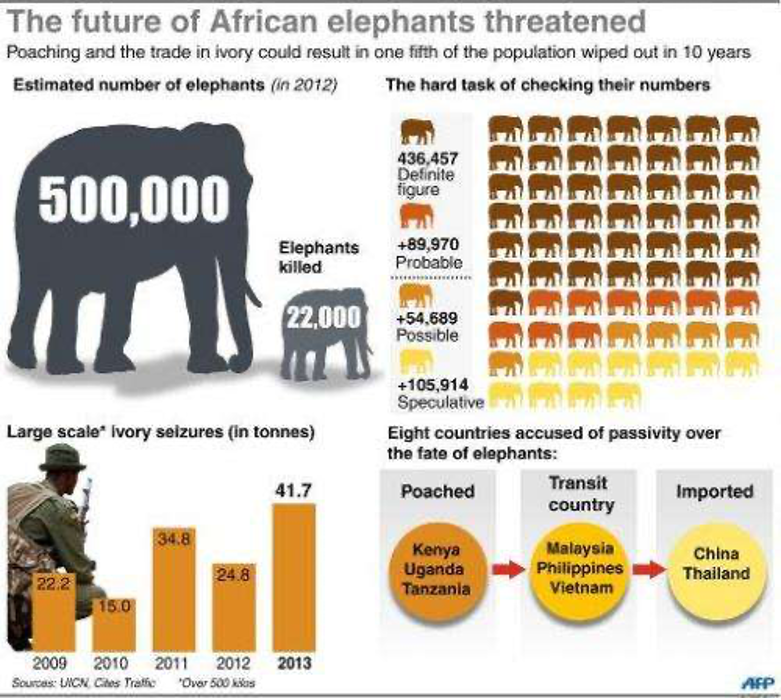

There is a global effect of the illegal wildlife trade. Africa, America, and Europe are now all part of the global wildlife product black market. However, UN-funded research shows that China is the world’s greatest consumer of legal and illegal animal goods (Gamso, 2023). This research backs up what the vast majority of others have found: The illegal wildlife trade has a significant presence in China.

Figure: Structure of Market

The supply networks fueling the illegal wildlife trade are centred in China and include Vietnam, Burma, and Thailand as crucial nodes. Nevertheless, the vast majority of commodities are en route to China or Japan from these nations. Several countries and provinces are involved in the global network of illegal wildlife trading, which stretches from the Far East to Eastern Europe. Research (Chakanyuka, 2020) shows that illegal wildlife trafficking in Asia originates in eastern, central, and southern Africa. When wild animals are murdered illegally for their skins, teeth, or other components, this practice is known as poaching.

Similar levels of cruelty are being meted out to plant populations, as are to sea turtles. It is not against the law to smuggle endangered species. Thousands of animals were herded, caught, and gathered for various reasons, including food, companionship, adornment, fashion, footwear, souvenirs, transportation, medicine, and so on (Roe, 2018). Due to rampant illegality and unsustainable practices in the wildlife trade, many plant species are in jeopardy. Everyone, from dealers to buyers, is complicit in the unlawful trafficking of ivory and rhino horn. Illegal revenues from the ivory and rhino horn trade can be estimated using the size of each market (Verssimo & Glikman, 2020). Several proportions can be estimated by comparing the expected total unlawful income with the annual rhino horn and ivory sales to consumers in target nations.

2.3 Demand – destinations, consumption, and methods of sale.

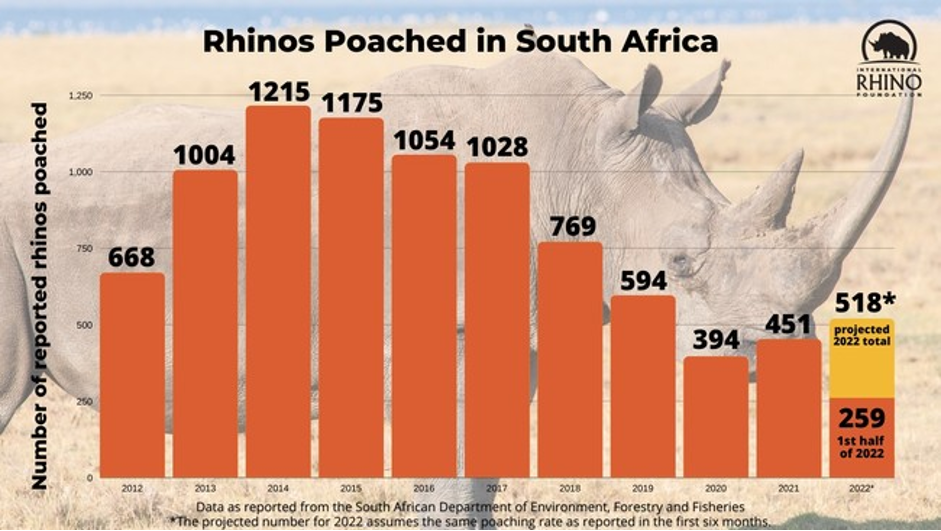

All around the world, people eat meat from various wild animals. Although rhino horn has been utilised for centuries in traditional Chinese medicine, it is now mostly valued for its status symbolism (Di Minin et al., 2022). Although Asia is home to most of the world’s rhino population, poachers remain a major threat to rhinos everywhere. The success of anti-poaching initiatives is increasingly important to field operations. Poachers have access to high-tech tracking and killing devices designed for rhinos thanks to transnational criminal networks (Verssimo & Glikman, 2020). Government supporters frequently put their lives in peril to defend rhinos from armed poachers.

The rapid decline in rhino populations in nations like Vietnam and China is directly correlated to the high demand for rhino horns in those countries. About 10,000 rhinos have been killed by poachers in Asia during the past decade. Once numbering in the hundreds of thousands, only about 30,000 Asian rhinos are now thought to remain (Berzaghi et al., 2022). Due to persistent misconceptions about its purported benefits, demand for rhino horn remains high. To satisfy demand and put a stop to the poaching epidemic, he proposes establishing a regulated market for rhino horns collected ethically from the few remaining rhinos (Roe & Booker, 2019). The private ownership of rhinos has many advantages, including the prevention of poaching, the creation of jobs, and the funding of anti-poaching efforts.

Figure: Elephant slaughter, ivory sales ‘out of control’: conservationists

Poachers in Eastern and Asian countries illegally killed about 1,070 rhinos between 2017 and 2019. All 29 animals’ combined pair of horns weighed in at a total of 5.56 kilograms (2.78 lb). A total of 30 horns were made out of the 2,100 that were produced. The horns of poached rhinos can add up to 31 tons (5.8 tons) in a single year. There was a shortage of 5,3 metric tons despite a declared collection rate of 91% in the field. It wasn’t just poached rhinos whose horns were sold on the black market. Stock theft, natural deaths, and poaching are all suspected of contributing to the disappearance of 113 horns (314 kg) from key bases (Baker, 2018). Between 2016 and 2018, it is estimated that 5.6 metric tons of rhino horn were traded illegally in Asia.

The term “wildlife trafficking” is used to characterise the unlawful trade in animals and plants that are protected by production limitations and licensing regulations (Atoussi et al., 2022). The rise of internet marketplaces and social media platforms has facilitated the sale of illegal animals and wildlife products. The widespread availability and exposure of the internet and social media could help combat the illegal wildlife trafficking. It’s possible that criminal groups may start using encrypted messaging apps more frequently for their own internal communication and coordination. The majority of the crimes that the Service’s Office of Law Enforcement looks into occur on some sort of online platform, be it a social network or a messaging app.

3.0 Conclusion and Recommendations

There is global concern over the illegal trade in wildlife. There are fewer bottlenecks for the billions of daily transactions on the platform because of the internet’s global reach. The amount of animals traded via online marketplaces, auction sites, and social media platforms is alarming. Despite the growing importance of online trade to the global economy, a sizable amount of it is almost certainly either unlicensed or illegal. Reducing the demand for IWT products, establishing strong legal frameworks and deterrents, bolstering law enforcement, and providing victims with long-term care are all necessary. The best and most effective strategies for shifting consumer tastes away from illicit animal products should be thoroughly understood by all parties.

These multinational agreements are subject to international rules and laws that have already been created and must be followed by local legal systems. Those who are interested in these themes are the ones who want more out of life than they can obtain through their DM relationships or their level of social and emotional intelligence. Although perception and comprehension appeals prioritise veracity and sound reasoning, sociocultural appeals prioritise education over amusement (Biggs et al., 2016). Instead of discussing the procedures used by appeal courts or the individuals (humans, elephants, rhinos) involved, this page focuses on the outcomes of IWT. The study also explains how the mechanics behind IWT were uncovered. The illegal trade in ivory and rhino horn consists of several different steps and is constantly evolving. The supply chain for ivory and rhino horn includes procurement, production, human smuggling, and retail sale. Those involved in the illegal trade of ivory and rhino horn rely heavily on the money they make from these activities. The majority of ivory and rhino horn on the black market comes from recent deaths. Factors like high intrinsic mortality and traffic offenses contribute just marginally to the whole. This means that poaching is the primary culprit.

The following are the recommendations and governance implications for policymakers and stakeholders who wish to combat IWT;

- It is possible that more agencies might work together to combat illegal wildlife trade if they had clearer plans, goals, and timetables for investigating wildlife crime, questioning suspects, and filing criminal charges. The number of wildlife trafficking instances in which organised crime played a role, the number of corruption scandals, and the number of enforcement actions conducted each year were also determined to be important indicators of success.

- If you have lofty goals that will require cooperation across departments, performance budgeting can help you relate spending plans and approval processes to those outcomes. As part of their study “Good Practices for Performance Budgeting,” the OECD delves thoroughly into these methods.

- In order to ensure that government employees fighting illegal wildlife trafficking have access to sufficient data, a gap and needs assessment should be conducted. More conversations and interactions at the operational level are needed between authorities of source, transit, and destination governments to build confidence and share operational data across borders with affected states.

- Make the required adjustments to the law to ensure its continued success. All species in the CITES classification should be specifically referenced in wildlife protections and fines in reaction to the widespread sale of endangered animals in domestic firms (with appropriate remedies per category).

- It is important to weigh the benefits and drawbacks of a complete prohibition on the trade of all ivory items, regardless of where they were created or when the elephants used to make them were killed, because there are always new ways for ivory goods to get through the cracks in the system.

- To ensure that only legally obtained ivory items are sold, it is imperative that stringent enrolment, monitoring, and tracking mechanisms be put in place. If a buyer or seller cannot produce the necessary paperwork, a fine or product seizure may be necessary.

- Captive breeding facilities and breeders need close observation. Science must verify the viability of the concept before a patent can be issued. Unless compelling justifications or reasons are provided, the current permissions must be revoked.

4.0 References

Atoussi, S., Razkallah, I., Zebsa, R., Bara, M., & Bensakhri, Z. (2022). Corruption and poaching in Algeria. African Journal of Ecology, 60(2), 182-183.

Baker, C.S., 2018. A more accurate measure of the market: the molecular ecology of fisheries and wildlife trade. Molecular Ecology, 17(18), pp.3985-3998. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03867.x

Berzaghi, F., Chami, R., Cosimano, T., & Fullenkamp, C. (2022). Financing conservation by valuing carbon services produced by wild animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(22), e2120426119.

Biggs, D., Caceres-Escobar, H., Kock, R., Thomson, G., and Compton, J., 2021. Extend existing food safety systems to the global wildlife trade: the Lancet Planetary Health, 5(7), pp.e402-e403. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(21)00142-X/fulltext

Biggs, D., Cooney, R., Roe, D., Dublin, H.T., Allan, J.R., Challender, D.W. and Skinner, D., 2016. Developing a theory of change for a community‐based response to the illegal wildlife trade. Conservation Biology, 31(1), pp.5-12. https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/cobi.12796

Chakanyuka, T. L. (2020). CITES and the African Elephant. Chinese Journal of Environmental Law, 4(1), 44-70.

Challender, D.W., Harrop, S.R. and MacMillan, D.C., 2018. Towards informed and multi-faceted wildlife trade interventions. Global Ecology and Conservation, 3, pp.129-148. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2351989414000791

Cooney, R., Roe, D., Dublin, H., Phelps, J., Wilkie, D., Keane, A., Travers, H., Skinner, D., Challender, D.W., Allan, J.R. and Biggs, D., 2016. From poachers to protectors: engaging local communities in solutions to illegal wildlife trade. Conservation Letters, 10(3), pp.367-374. https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/conl.12294

Di Minin, E., Selier, J., Louis, M., & Bradshaw, C. J. (2022). Dismantling the poachernomics of the illegal wildlife trade. Biological Conservation, 265, 109418.

Esmail, N., Wintle, B.C., t Sas‐Rolfes, M., Athanas, A., Beale, C.M., Bending, Z., Dai, R., Fabinyi, M., Gluszek, S., Haenlein, C. and Harrington, L.A., 2020. Emerging illegal wildlife trade issues: A global horizon scan. Conservation Letters, 13(4), p.e12715. https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/conl.12715

Fukushima, C.S., Mammola, S. and Cardoso, P., 2020. Global wildlife trade permeates the Tree of Life—Biological Conservation, 247, p.108503. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006320720300677

Gamso, J. (2023). Aiding Animals: Does Foreign Aid Reduce Wildlife Crime?. The Journal of Environment & Development, 32(1), 34-60.

Hauenstein, S., Kshatriya, M., Blanc, J., Dormann, C. F., & Beale, C. M. (2019). African elephant poaching rates correlate with local poverty, national corruption and global ivory price. Nature Communications, 10(1), 2242.

Leimgruber, P., & Songer, M. A. (2021). Conservation: Where can elephants roam in the Anthropocene?. Current Biology, 31(11), R714-R716.

Margulies, J.D., Bullough, L.A., Hinsley, A., Ingram, D.J., Cowell, C., Goettsch, B., Klitgård, B.B., Lavorgna, A., Sinovas, P. and Phelps, J., 2019. Illegal wildlife trade and the persistence of “plant blindness.” Plants, People, Planet, 1(3), pp.173-182. https://nph.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ppp3.10053

McDonald, E. (2016, January). Too Big to Fail: Rescuing the African Elephant. In The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs (pp. 113-131). The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.

McNamara, J., Rowcliffe, M., Cowlishaw, G., Alexander, J.S., Ntiamoa-Baidu, Y., Brenya, A. and Milner-Gulland, E.J., 2016. Characterising wildlife trade market supply-demand dynamics. PloS one, 11(9), p.e0162972. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0162972

Milner-Gulland, E.J., Cugniere, L., Hinsley, A., Phelps, J. and Veríssimo, D., 2018. Evidence to Action: Research to address the illegal wildlife trade. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327431598_Evidence_to_Action_Research_to_Address_Illegal_Wildlife_Trade

Phelps, J., Biggs, D. and Webb, E.L., 2016. Tools and terms for understanding the illegal wildlife trade. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 14(9), pp.479-489. https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/fee.1325?saml_referrer

Robinson, J.E., Griffiths, R.A., Fraser, I.M., Raharimalala, J., Roberts, D.L. and St. John, F.A., 2018. Supplying the wildlife trade as a livelihood strategy in a biodiversity hotspot. Ecology and Society, 23(1). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26799042?seq=3

Roe, D. and Booker, F., 2019. Engaging local communities in tackling illegal wildlife trade: A synthesis of approaches and lessons for best practice. Conservation Science and Practice, 1(5), p.e26. https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/csp2.26

Roe, D., 2018. Trading nature: a report, with case studies, on the contribution of wildlife trade management to sustainable livelihoods and the Millennium Development Goals. https://www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/5332/traffic_pub_gen19.pdf

Sas-Rolfes, M., Challender, D.W., Hinsley, A., Veríssimo, D. and Milner-Gulland, E.J., 2019. Illegal wildlife trade: Scale, processes, and governance. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 44, pp.201-228. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-environ-101718-033253

Schlossberg, S., Chase, M. J., Gobush, K. S., Wasser, S. K., & Lindsay, K. (2020). State-space models reveal a continuing elephant poaching problem in most of Africa. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 10166.

Sosnowski, M. C., Knowles, T. G., Takahashi, T., & Rooney, N. J. (2019). Global ivory market prices since the 1989 CITES ban. Biological Conservation, 237, 392-399.

write

write