Abstract

Background and Purpose: The duration of hospitalization for stroke rehabilitation patients is a crucial measure of healthcare utilization and cost. More severe strokes and additional medical conditions lead to longer lengths of stay (LOS). LOS is the primary predictor of hospital expenses and the overall cost of hospitalization. The average LOS fluctuates across geographic regions and specific hospitals. While self-management abilities in stroke patients improve outcomes and self-efficacy after discharge, there needs to be more understanding of effective processes to build these skills before leaving the hospital.

Case Description: Early-supported discharge (ESD) services for stroke patients may be administered by a discrete ESD team, a community rehabilitation service, or an acute stroke team, among others. Irrespective of the framework, it is standard practice for ESD services to administer rigorous therapy (with occupational, physical, and speech therapy, each comprising a maximum of five sessions per week) for the identical duration of time that the patient would have been enrolled in inpatient rehabilitation, which is typically between two and six weeks. ESD aims to facilitate the transition of appropriate stroke patients from inpatient rehabilitation to ongoing rigorous therapy, either remotely or in an outpatient environment, for the equivalent duration of time that they would have spent in the hospital. This permits early discharge of patients while ensuring they continue receiving sufficient rehabilitation to aid their recovery.

Outcomes: The expected outcomes of early supported discharge services are decreased healthcare costs, smooth transition from hospital to home, shortened hospital length of stay, improved health and quality of life outcomes based on specific criteria and measures, reduced caregiver burden, enhanced patient and caregiver experience, fewer unnecessary hospital readmissions, achievement of national and local performance benchmarks, and reduced risk of secondary complications such as pressure The overriding goals are to speed up recovery, reduce hospitalization, improve outcomes, lower expenses, and improve the overall experience for stroke patients and caregivers.

Discussion: The success of early-supported discharge programs depends on health systems’ willingness to employ innovative treatment paths for stroke patients. Success benefits include better patient outcomes, fewer problems and expenses, and high-quality scores that boost public appreciation and reimbursement. This program could be marketed to additional acute care hospitals, community rehabilitation institutions, and home health organizations. Reputation, quality of care, reduction of complications and expenses, and quality are improved by establishing and enhancing procedures with cooperation. The framework is successful for use in many health contexts.

Background and Purpose

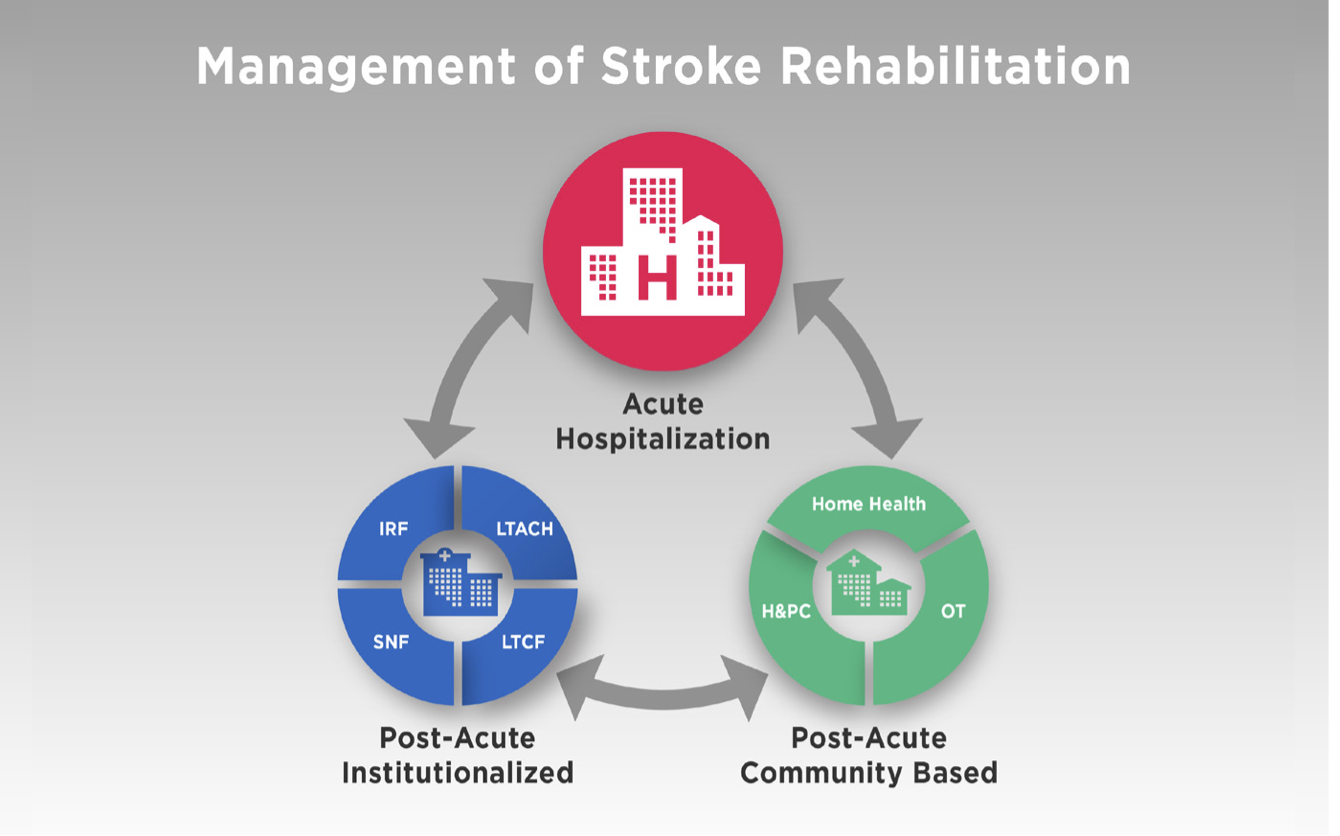

After a stroke, care is often split into two paths that need to be better organized. Care pathways are not always organized, so they do not always follow the different stages of rehabilitation after a stroke, such as the acute phase of treatment, rehab in a hospital, and rehab at home (Fisher et al., 2020). These steps are often separated, and there are no excellent communication or transition plans between acute care hospitals, inpatient rehab facilities, outpatient rehab clinics, and community programs. Because of this, the growth of this treatment has become random, broken up, interrupted, and stopped.

Patients who have had a stroke need interdisciplinary rehabilitation in a hospital to get the most out of their healing and results. People who have had a stroke and start their rehab program as soon as possible after being hospitalized have a better chance of getting better than people whose rehab programs start later or are limited (Chien et al., 2020). Patients who have had a stroke and do not get comprehensive, intensive care are at risk for complications like falls, pressure sores, joint contractures, more brain damage from not moving around, muscle loss, and general physical deconditioning while they are in the hospital. LOS tracking for stroke rehabilitation is essential for determining how resources are used and how much they cost (Chouliara et al., 2023). As the time of hospitalization is mainly determined by the severity of the stroke and other health problems, there is a strong link between this and the total cost of hospitalization. LOS can vary a lot from hospital to hospital and area to region. Jee et al. (2022), a medicare study from 2002, found that it usually takes 12.4 days for someone who has had a stroke to get better and start getting post-acute care. The most current data from the NIH showed that the ALOS was 8.9 days for mild strokes, 13.9 days for moderate strokes, and 22.2 days for severe strokes. This time, shorter lengths of stay in rehab were caused by more work for the administration; some centres saw reductions of as little as one week. Still, community-based rehabilitation alone is not always enough to ensure patients are appropriately discharged and have the help and follow-up they need after they leave the hospital.

Many countries have established standardized stroke care pathways for patients with mild to moderate post-stroke disability, allowing for early discharge and home-based rehabilitation. Best practices for discharge planning and home-based care are outlined in the Stroke Foundation National Stroke Rehabilitation Guideline in Australia, the Canadian Stroke Network guidelines in Canada, the Danish Stroke Society national plan in Denmark, US’s American Stroke Association, and the Finnish Stroke Association recommendations which are just some of the examples in different countries (Fisher et al., 2021; Jee et al., 2022; Leach et al., 2020). These types of post-release treatment are referred to as “early supported discharge” (ESD). However, these practices vary from country to country. Stroke patients in the United States go through several stages of post-acute care rehabilitation, beginning with inpatient rehabilitation and progressing to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), long-term acute care (LTACs), outpatient treatment, and finally, home health care. Currently, no standards provide an expedited pathway for stroke patients to return home after discharge. Each level of treatment is associated with varying degrees of medical expenditure. In contrast, Early Supported Discharge (ESD) in nations such as England entails a coordinated transfer of care from the hospital to a patient’s home to provide timely rehabilitation from a multidisciplinary team (Jee et al., 2022). Stroke care guidelines in England and worldwide promote ESD as part of an evidence-based stroke care pathway, citing strong evidence of its benefits.

Home rehabilitation programs are designed to meet the same standards and intensity levels as inpatient rehabilitation units. Only around one-third of acute stroke occurrences fit the criteria for the Early Stroke Discharge program based on their functional capacity and medical requirements (Chang et al., 2021). Higher-functioning ESD programs allow patients to return home from expensive institutional care sooner, resulting in a higher independence rate in fundamental living tasks upon discharge. Numerous studies have found that ESD is cost-effective, as is maintaining patients in regular hospital wards or stroke units that do not use ESD methods. In other countries, such as Sweden, where the healthcare system is robust (the average stay in a stroke rehabilitation program is only 12 days), ESD programs are developed and thoroughly integrated into national guidelines (Leach et al., 2020; Chien et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2021). In England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, about 81% of hospitals have ESD coordinating teams dedicated to stroke management. Approximately 35% of the patients are treated (Fisher et al., 2021).

On the other hand, most other European and high-income countries do not have ESD in their systems. Chiu et al. (2021) in the EU, ESD is either nonexistent or implemented only at the local or even inferior level in a single or a few particular areas for the nations with available data, half of which are covered. The primary benefit of early stroke discharge is that it allows for intensive stroke therapy at residential institutions while ensuring a safe and supported transition from specialized inpatient care units to the community (Langton-Frost et al., 2023). It continues to provide resistance to hypertrophy at home with the same quality as hospital facilities. To ensure continuity of care, ESD treatments must begin by 24 hours after hospital discharge for qualifying patients.

Inpatient recovery is challenging for most people who have had a stroke, and a lot of them have to go back home after that. This happens a lot because patients are thought to be at a high risk of either not planning and getting ready for their shift well enough before they leave the hospital or making mistakes, getting sick, or being hurt at home after they get to go, which can be avoided. Chiu et al. (2021) assert that teaching patients how to handle their problems improves their outcomes and sense of self-efficacy after they leave the hospital. However, what processes and interventions are best for enhancing skills before they go are still unclear or understood.

Early supported discharge (ESD) is one of the best ways to care for people (Chang et al., 2021). It makes the change from inpatient rehabilitation to integrated community-based care smooth by linking the rehabilitation care people get in hospitals with the tracking and rehabilitation care they get at home. With this fact, the US healthcare system uses fewer ESD models than other countries. As such, there are a variety of healthcare systems, financing models, cultures, and the most favoured institutional medical delivery models that may vary by country.

Today, the doctors and clinic specialists brainstormed the health care and the independence model. Leach et al. (2020) proved that the COMPASS program successfully treats stroke patients. Community Partnership for Achieving ServiceCoordinationn and Satisfaction (COMPASS) is an interdisciplinary model for coordinating care in the wider local community, in which clinicians collaborate with community teams to lead. The COMPASS model targeted to the stroke patient group that solely emphasizes the needs of patients after discharge and aftercare is presented by Duncan et al. (2020).

The purpose of organizing this case study is to assist students in comprehending the development and implementation of the so-called blended model with outreach components, which is a suitable way of management for post-stroke people with mild-to-moderate impairments who are discharged from hospital rehabilitation as NHS in the UK recommends. Moreover, the data available now suggests that opening the selective endovascular drainage for a specific group of stroke patients could reduce people’s dependency on these techniques for longer, resulting in faster independence, shorter hospitalizations, and reduced medical expenses.

Case Description: Target Setting

Three Crosses Community Hospital is the site of this project. In Las Cruces, New Mexico, there is an acute care hospital called Three Crosses Community Hospital with ten beds. They operate smoothly with two medical clerks on staff and a nurse-to-patient ratio of 1:2, an ideal ratio for any hospital (Fisher et al., 2020). The hospital accommodates up to 10 patients for inpatient acute care. Southwest Sports and Spine, Inc. in Las Cruces, comes to Three Crosses to help with therapy. Not only that, but Three Crosses does not treat neurological conditions, and it does not have any plans to shorten the stays of stroke patients. The NIH found that in 2018, the average length of stay for all medical illnesses was 5.5 days. This causes more problems for the patients and costs more because they have to stay in the hospital longer. The average person who has had a stroke should stay at the Johns Hopkins Center for seven days.

The city of El Paso, Texas, is right next to Las Cruces. El Paso has so many hospitals. Although New Mexico is a low-income state overall, Las Cruces needs more hospitals and other healthcare facilities that are up to par. A person might be able to get care at the hospital, but they would have to drive 45 minutes to get to El Paso. Therefore, the lack of post-acute rehabilitation facilities in Las Cruces makes it difficult because patients not yet ready to be sent home must be moved to places like Silver City, Truth or Consequences, or Albuquerque to get skilled care.

The ESD team at Three Crosses Hospital will make three significant changes to how stroke patients are cared for that will work. In terms of ESD, this can shorten stays and avoid readmissions for 30 days. It can also help people become more independent and safely go home, improving the total quality and value of the care (Chien et al., 2020). Through ESD, patients from the surrounding area can get high-quality sub-acute stroke care close to home.

Development of the Process

ESD has yet to be implemented in the United States, so we can look to successful models from countries like Canada, the UK, and Europe to develop community-level ESD at Three Crosses Hospital. In the UK, ESD teams consist of speech and language therapists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, specialist nurses, and rehab assistants – all with specialized stroke skills (Chouliara et al., 2023). They are all trained to help people who have had a stroke. In the acute care unit at Three Crosses, there are CNAs, RNs, PTs, OTs, SLPs, NPs, attending doctors, specialists, PAs, quick response teams, dietitians, pharmacists, patient advocates, and more (O Connor et al., 2024). Home health rehab is mainly done by therapists (PT, OT, SLP), support workers, nurses, and sometimes RNs, NPs, and MDs.

Due to this, ESD must be done with the help of all the essential staff members from different departments and roles. However, only involving department heads could make it harder for direct care staff to communicate. As part of the organization’s processes, there must be meetings with CNAs, RNs, floor nurses, physical therapy specialists, patient advocates, social workers, and case managers. This is the group that could make up the ESD team. It could have SLPs, OTs, OTAs, PTs, PTAs, a dedicated doctor, and an RN. All providers must get specialized training in stroke to give the best ESD care to the patient (Horvath, 2024). This interdisciplinary development process tapping both managerial and bedside staff can lead to an invested ESD team tailored to Three Crosses’ existing human resources but with specialized stroke training. This method offers adapted care settings for people who are not yet able to be when they are not ready to be released.

An efficient ESD program requires developing, implementing, and maintaining a cooperative, interdisciplinary team. Leaders in nursing, therapy services, case management, social work, and hospital administration are essential groups that should be involved (Southerland et al., 2020). These team members need to commit to meeting at least once a month to be involved in all stages of planning and keeping an eye on things. Getting buy-in and support from all areas is very important because if people are not involved, the program’s goals and patient outcomes could be harmed or even stopped.

As soon as the ESD program is approved, the core team should work closely with department experts to set up detailed policies, procedures, protocols, and roles for each person within the first month. Being clear about the program’s goals, outcomes, and steps is essential. For example, who should be eligible for ESD, when the first home visit should happen after release, how often the team meets, how to keep records, train families and caregivers, and track outcome metrics. Processes should focus on learning about and considering each patient’s tastes whenever possible.

The first visit to the patient’s home within 24 hours of release is crucial for ensuring they are safe and getting extra medical tools. For the best recovery outcomes, caregivers need to be involved and receive intense training in providing care, using assistive techniques, and keeping an eye on things. According to the latest standards, tests based on evidence are used. These include the Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale, the Stroke Impact Scale, and the Stroke Rehabilitation Assessment of Movement (Ishige et al., 2022).

As a result, the ESD team takes on numerous duties, including offering education and assistance to stroke survivors, family members, and caregivers. This includes or gives each patient specific things geared toward their rehabilitation wants and goals. Their main job is to provide information on patient-specific goods like devices for safety and independence, do assessments, and make suggestions (Herssen et al., 2021). They also give their patients access to bulletin boards that list tools like exercise programs, ways to avoid having a stroke, and services that are easy to get after they leave the hospital.

The ESD program will offer health care through an Outreach Model of Transitional Care. The ESD model has the acute hospital team find patients who are good candidates for ESD, make a safe discharge plan that may include making changes to the patient’s home, and give the patients a time of intensive rehabilitation right after they are sent home (usually, the patients are followed up on for up to two weeks) (Lutz et al., 2020). Once the full-service early post-stroke transitional process is over, the patients get recovered by community outpatient teams trained in stroke care. In this situation, the acute release and community teams need to work together and get along so that care can continue as planned.

According to Sezgin et al. (2020), NHS England says that an older person must be able to get from one place to another with the help of a caregiver or partner if they live with someone, or they must be able to travel on their own if they live alone to be eligible for elderly day services. While most experts in ESD trials agree that the admission requirements should be flexible for the sake of research and clinical utility (i.e., to make sure that the target populations are feasible and acceptable), patients should be judged on their ability to receive treatments based on clinical judgment rather than specific impairment measures used to pick patients who are most likely to respond to interventions. Also, this means that people whose needs are very high and require much help can still be sent home with less complete hospice home care (Southerland et al., 2020). The ESD program does not work with people based on their race, disability, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, age, or any other protected trait.

The ESD service team will build meaningful relationships and care coordination protocols with the following key groups: inpatient rehab centres for stroke and neurology, social services, home health agencies, primary care providers, volunteer groups, mental health and behavioural clinics, psychological therapy services, urgent care centres open after hours, podiatry, nutrition, dental, orthotics, wheelchair and equipment providers, and community exercise facilities. To avoid gaps between agencies and ensure smooth transitions, ESD, primary care, secondary care, social services, and all other related providers must work together without any problems. This could mean ESD staff attends meetings about planning patient release, sets up pre-discharge outreach, names care coordinators, arranges collaborative reviews, and shares relevant patient information. There should also be regular meetings of the multidisciplinary ESD team.

The ideal NHS staffing for ESD is one full-time coordinator or team lead, one full-time specialist nurse, one full-time physical therapist, one full-time occupational therapist, 0.4 full-time speech therapists, one full-time psychologist, rehabilitation assistants trained in stroke care, 0.5 full-time social workers, and administrative and clerical roles. It is based on treating 100 patients annually (Ishige et al., 2020).

The ESD office room should have desks, chairs, IT equipment, and locked file cabinets. There needs to be a designated phone line with voicemail, a safe fax machine, and a printer. The clinical staff will have cell phones to get immediate referrals and talk to partners. When staff go to people’s homes or communities, they bring infection control supplies for washing their hands and essential tools for moving people. The environment has to meet health and safety guidelines set by the law and the WHO. The provider is in charge of getting and keeping up with rehabilitation tools. For patients to stay safe at home, they must get the right assistive tools as soon as possible. Essential equipment must be able to be prescribed by all clinical staff. More complicated items may need to be approved by the team head (Sezgin et al., 2020). The equipment needs and regular checks should be discussed during the first home visit.

For people to be eligible for ESD, they must meet the following requirements:

- Be at least 16 years old.

- Be registered with a local primary care provider.

- Get a new stroke diagnosis confirmed by a visiting neurosurgeon and a CT scan.

- Be physically stable enough to go home, as determined by the doctor.

- Provide consent to participate in ESD, with agreement from caregivers as applicable.

- Must be ready and willing to follow the personalized exercise plan and goals set before leaving the hospital.

- Have the ability to transfer themselves or with help from a trained helper. However, experts say that the ability to communicate should be flexible so that patients who need more help can still benefit from ESD.

- Take care of their own or someone else’s health and toileting needs.

- Be able to use a computer or a caregiver to get help if they need it, either one-on-one or a variety of therapies, as decided by the care team.

- Have a home setting that the evaluating inter-professional team says is safe and good for ESD.

The goal is to develop reasonable but flexible eligibility requirements so that expert clinical judgment and careful consideration of each patient’s unique situation can be used to find those most likely to benefit from intense transitional support through ESD.

Application of the Process

Assessment: The ESD process will begin with thoroughly evaluating each patient’s needs, goals, and living conditions. A key worker will be tasked with overseeing and coordinating the implementation of the tailored ESD care plan, as well as facilitating any necessary referrals. The stroke survivor will provide informed consent to undertake assessments collaboratively with family members and caregivers. Assessments and goal-setting will be based on each individual’s objectives, values, and needs. The key worker will present the patient and family with tailored evaluation results, rehabilitation goals, and a thorough ESD care plan (Lutz et al., 2020). If any social service requirements are found during the evaluation, the care plan will involve communication with social services to arrange for necessary support. Patients with informal caregivers will be referred to social services for a Carers Needs Assessment to assess whether further assistance is required. Care plans will be reassessed and updated throughout the ESD process to maintain the best quality of tailored transitional care. Patients and families will participate in all assessment and care planning activities (Merluzzi et al., 2024). The team must ensure that the patient and their caregiver(s) understand what has occurred to them and what to expect. Specialist stroke rehabilitation and assistance will treat stroke-related concerns directly or, if necessary, through referral.

Intervention: Patients will receive tailored ESD services for the first six weeks after release from the hospital. ESD can involve up to five weekly rehabilitation sessions, including occupational therapy, physical therapy, speech therapy, nursing care, and other services suited to each patient’s needs (García-Pérez et al., 2022). Some may need one or two visits from a single field, while others require six weeks of interdisciplinary therapy. For patients who require nursing care, the ESD nursing team should make a home visit within 24 hours of their hospital release. Some rehabilitation interventions may be carried out by trained assistants such as CNAs, PTAs, or COTAs while supervised by a skilled clinician. According to NHS guidelines, professional rehabilitation aides from the ESD team can provide short-term personal care needs that do not require ongoing social services (Auger et al., 2023). However, the NHS does not define the essential qualifications for these positions. Thus, credentials and competencies must be produced.

Throughout ESD, frequent reassessments and care plan reviews via MDT and patient/family meetings are required to track progress toward targets. Following review, patients may continue with ESD, move to outpatient community rehabilitation, be discharged if goals get fulfilled, or be referred to other necessary services. ESD’s intensity, frequency, and duration will be re-evaluated and modified regularly to ensure patients transition safely while maintaining functional independence (Connor et al., 2023). Clear policies on rehabilitation assistant credentials and supervision are required to provide quality care.

Patients will be sent home or referred to physical therapy or home health care extension after completing a specific early supported discharge (ESD) program. The area has no particular stroke outpatient facilities or health clinics, but London’s Strategic Clinical Networks believe these will be the most appropriate sites (García-Pérez et al., 2022).

The primary goals of this ESD program are self-management and maximal independence. Patients should be able to care for long-term diseases to the greatest extent possible, although they may get directed to the self-management plan and expert-patient classes for assistance. The translators should be provided for patients who require assistance. These should be transcribed into the target languages. Stroke patients and caregivers should receive applicable written or printed information and education packets (Auger et al., 2023). Advice on how to use and apply them should also be provided. These can cover many topics, such as lifestyle diet, weight control, and smoking cessation. The majority of stroke victims suffer from severe cognitive and communication difficulties, such as aphasia. The material should be tailored to the patient’s communication ability, and images or diagrams can help with comprehension. The goal is to increase self-efficacy through tailored instruction and help.

Outcome

Patients with stroke can receive prompt and coordinated early supported discharge (ESD) for home-based rehabilitation, reducing hospital stays while improving outcomes because intensive therapy is also delivered. ESD is expected to save healthcare costs, improve quality of life and function, minimise caregiver load, enhance the experience, limit unneeded readmissions, meet quality requirements, and reduce complications (Connor et al., 2023). ESD typically begins immediately after hospital discharge, aims to increase rehabilitation intensity, assists patients in managing their day-to-day activities on their own, demonstrates improvements across multiple domains (e.g., costs, metrics, and patient experience), reduces the risk of developing secondary health issues, and ensures stroke rehabilitation is evidence-based and by standards. A well-run ESD necessitates the involvement of multiple systems and individuals’ active participation in their health management.

Discussion

Adopting an early supported discharge (ESD) program at Three Crosses Hospital for stroke patients can help ensure a prompt and coordinated transition to home-based rehabilitation. It shortens hospital stays while still allowing intensive therapy to improve functional results. Based on evidence from successful ESD models around the world, this approach is thought to lower healthcare costs, raise patient satisfaction, promote independence and quality of life, ease the burden on caregivers, stop patients from needlessly returning to the hospital, help meet quality standards, and lower the risk of complications (Shahid et al., 2023).

Everyone involved—the hospital staff, doctors, nurses, therapists, social workers, case managers, community providers, patients, and caregivers—must be committed and on board to get these benefits. Support from leaders is essential, even if some area heads do not want to help at first. Over time, ESD can be supported by teaching people about its evidence and focusing on how it can help reduce work and improve results (Lee et al., 2024). Even if people do not want to follow through initially, administrative leadership and expert support can make it easier.

As the ESD program strengthens, some temporary programs may be shut down. This will free up money that can be used to improve quality or move to areas that need it. Looking at how ESD affects staff retention, efficiency, income, and the difference between costs and reimbursement is essential in the long term. The scheme must be changed as new evidence comes in (Cameron et al., 2023). For instance, technology like apps that analyze the gait could added once proven to work well enough. The ESD team needs to know about the newest methods to change the rules to fit.

This ESD program can help other hospitals and post-acute care providers make the transfers for stroke patients better. There are, however, some problems and areas that need more study. The eligibility requirements need to be improved to include more suitable people. There needs to be more information about what makes ESD hard and accessible in the US. Locally, cost-effectiveness and budget effects should be examined (Lee et al., 2024). Also, the best ways to hire and train people must be figured out. Follow-up studies must be done on patients’ adherence, involvement, and long-term outcomes.

In conclusion, an early-supported discharge program has much promise to make rehabilitation after a stroke better and more valuable. However, working together, getting trained, having good guidance, and constantly improving things will be critical to its success. This project can help more people use ESD and find knowledge gaps that can guide future studies. With much work, ESD could become the new standard of care for helping stroke patients make safe, timely, and effective transitions.

References

Auger, L. P., Moreau, E., Côté, O., Guerrera, R., Rochette, A., & Kairy, D. (2023). Implementing Telerehabilitation in an Early Supported Discharge Stroke Rehabilitation Program before and during COVID-19: An Exploration of Influencing Factors. Disabilities, 3(1), 87-104.https://www.mdpi.com/2673-7272/3/1/7

Cameron, T. M., Koller, K., Byrne, A., Chouliara, N., Robinson, T., Langhorne, P., … & Fisher, R. J. (2023). A qualitative study exploring how stroke survivors’ expectations and understanding of stroke Early Supported Discharge shaped their experience and engagement with the service. Disability and Rehabilitation, 45(16), 2604–2611.https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09638288.2022.2102251

Chang, W. K., Kim, W. S., Sohn, M. K., Jee, S., Shin, Y. I., Ko, S. H., … & Paik, N. J. (2021). Korean model for post-acute comprehensive rehabilitation (KOMPACT): The protocol for a pragmatic multicenter randomized controlled study on early supported discharge. Frontiers in Neurology, 12, 710640.https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2021.710640/full

Chien, S. H., Sung, P. Y., Liao, W. L., & Tsai, S. W. (2020). A functional recovery profile for patients with stroke following post-acute rehabilitation care in Taiwan. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 119(1), 254-259.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0929664619302190

Chiu, C. C., Wang, J. J., Hung, C. M., Lin, H. F., Hsien, H. H., Hung, K. W., … & Shi, H. Y. (2021). Impact of multidisciplinary stroke post-acute care on cost and functional status: A prospective study based on propensity score matching. Brain Sciences, 11(2), 161.https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3425/11/2/161https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3425/11/2/161

Chouliara, N., Cameron, T., Byrne, A., Lewis, S., Langhorne, P., Robinson, T., … & Fisher, R. (2023). How do stroke early-supported discharge services achieve intensive and responsive service provision? Findings from a realist evaluation study (WISE). BMC Health Services Research, 23(1), 1–12.https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-023-09290-1

Chouliara, N., Cameron, T., Byrne, A., Lewis, S., Langhorne, P., Robinson, T., … & Fisher, R. (2023). How do stroke early-supported discharge services achieve intensive and responsive service provision? Findings from a realist evaluation study (WISE). BMC Health Services Research, 23(1), 1–12.https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-023-09290-1

Connor, E. O., Dolan, E., Horgan, F., Galvin, R., & Robinson, K. (2023). A qualitative evidence synthesis exploring people after stroke, family members, carers, and healthcare professionals’ experiences of early supported discharge (ESD) after stroke. Plos one, 18(2), e0281583.https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0281583

Duncan, P. W., Bushnell, C. D., Jones, S. B., Psioda, M. A., Gesell, S. B., D’Agostino Jr, R. B., … & COMPASS Site Investigators and Teams. (2020). Randomized pragmatic trial of stroke transitional care: the COMPASS study. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 13(6), e006285.https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.006285

Fisher, R. J., Byrne, A., Chouliara, N., Lewis, S., Paley, L., Hoffman, A., … & Walker, M. F. (2020). Effectiveness of stroke early supported discharge: analysis from a national stroke Registry. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 13(8), e006395.https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.006395

Fisher, R. J., Chouliara, N., Byrne, A., Cameron, T., Lewis, S., Langhorne, P., … & Walker, M. F. (2021). Large-scale implementation of stroke early supported discharge: the WISE realist mixed-methods study. Health Services and Delivery Research, 9(22).https://eprints.gla.ac.uk/259594/

García-Pérez, P., Lara, J. P., Rodríguez-Martínez, M. D. C., & de la Cruz-Cosme, C. (2022, August). Interventions within the Scope of Occupational Therapy in the Hospital Discharge Process Post-Stroke: A Systematic Review. In Healthcare (Vol. 10, No. 9, p. 1645). MDPI.https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/10/9/1645

Herssens, N., Swinnen, E., Dobbels, B., Van de Heyning, P., Van Rompaey, V., Hallemans, A., & Vereeck, L. (2021). The relationship between the activities-specific balance confidence scale and balance performance, self-perceived handicap, and fall status in patients with peripheral dizziness or imbalance. Otology & Neurotology, 42(7), 1058-1066.https://journals.lww.com/otology-neurotology/_layouts/15/oaks.journals/downloadpdf.aspx?an=00129492-202108000-00028

Horvath, B. (2024). Skilled Nursing Facility Interventions: Interdisciplinary Collaboration Between Therapists And Certified Nursing Assistants. Gerontology.https://www.occupationaltherapy.com/articles/skilled-nursing-facility-interventions-interdisciplinary-5665

Ishige, S., Wakui, S., Miyazawa, Y., & Naito, H. (2022). Psychometric properties of a short version of the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale-Japanese (Short ABC-J) in community-dwelling people with stroke. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 38(11), 1756-1769.https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09593985.2021.1888342

Jee, S., Jeong, M., Paik, N. J., Kim, W. S., Shin, Y. I., Ko, S. H., … & Sohn, M. K. (2022). Early supported discharge and transitional care management after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Neurology, 13, 755316.https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2022.755316/full

Langton-Frost, N., Orient, S., Adeyemo, J., Bahouth, M. N., Daley, K., Ye, B., … & Pruski, A. (2023). Development and implementation of a new model of care for patients with stroke, acute hospital rehabilitation intensive services: Leveraging a multidisciplinary rehabilitation team. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 102(2S), S13-S18.https://journals.lww.com/ajpmr/Fulltext/2023/02001/Development_and_Implementation_of_a_New_Model_of.4.aspx

Leach, K., Neale, S., Steinfort, S., & Hitch, D. (2020). Clinical outcomes for moderate and severe stroke survivors receiving early supported discharge: A quasi-experimental cohort study. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 83(11), 680–689.https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0308022620939860

Lee, H. M., Mercimek-Andrews, S., Horvath, G., Marchese, D., Poulin III, R. E., Krolick, A., … & Hwu, W. L. (2024). A position statement on patients with aromatic I-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency post-gene-therapy rehabilitation. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 19(1), 17.https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13023-024-03019-x

Lutz, B. J., Reimold, A. E., Coleman, S. W., Guzik, A. K., Russell, L. P., Radman, M. D., … & Gesell, S. B. (2020). Implementing a transitional care model for stroke: perspectives from frontline clinicians, administrators, and COMPASS-TC implementation staff. The Gerontologist, 60(6), 1071-1084.https://academic.oup.com/gerontologist/article-abstract/60/6/1071/5818705

Merluzzi, T. V., Salamanca-Balen, N., Philip, E. J., Salsman, J. M., & Chirico, A. (2024). Integrating Psychosocial Theory into Palliative Care: Implications for Care Planning and Early Palliative Care. Cancers, 16(2), 342.https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/16/2/342

O Connor, E., Dolan, E., Horgan, F., Galvin, R., & Robinson, K. (2024). Healthcare professionals’ experiences delivering a stroke Early Supported Discharge service–An example from Ireland. Clinical Rehabilitation, 02692155231217363.https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/02692155231217363

Sezgin, D., O’Caoimh, R., Liew, A., O’Donovan, M. R., Illario, M., Salem, M. A., … & all EU ADVANTAGE Joint Action Work Package 7 partners. (2020). The effectiveness of intermediate care including transitional care interventions on function, healthcare utilization, and costs: a scoping review. European geriatric medicine, 11, 961-974.https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41999-020-00365-4

Shahid, J., Kashif, A., & Shahid, M. K. (2023). A Comprehensive Review of Physical Therapy Interventions for Stroke Rehabilitation: Impairment-Based Approaches and Functional Goals. Brain Sciences, 13(5), 717.https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3425/13/5/717

Southerland, L. T., Lo, A. X., Biese, K., Arendts, G., Banerjee, J., Hwang, U., … & Carpenter, C. R. (2020). Concepts in practice: geriatric emergency departments. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 75(2), 162–170.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S019606441931114X

Appendix

write

write