Introduction

As long as humans have lived, art has existed in one form or another – it is a fundamental part of human life (Livni, 2018). Evidence found in prehistoric Africa shows that early humans were used to painting their artifacts, with discoveries of paint containers lending more credence to this assertion. Humanoid carvings called Venus Figurines have been discovered across Europe in Germany, and Austria, and cave paintings in France, Ukraine, Italy, and Spain (H. W. Janson, 2001). This interest in art continued throughout human history from antiquity through the Middle Ages to the Age of Enlightenment, and the present, with each period featuring more refined art than the preceding period, from the simple styles of the middle stone age to the present form. Art has been used as a medium to preserve history, as a form of communication, and as a symbol of a higher power, thus reinforcing its relevance to human development and experience (Livni, 2018). This essay reviews the life and works of five of the most impactful European visual artists through the different historical periods, their influences, and their legacy.

Duccio di Buoninsegna

One of the most prolific artists and painters of the Middle Ages, Duccio was born in 1319 in Siena, Italy. He worked mostly in Tuscany and its vicinity (Boskovits, 2016). Although no evidence exists, there are speculations that he also traveled and worked in Rome (1280-1285), Assisi, and Paris. However, his most renowned workplace was in Siena, where he gained significant commissions, including the Maesta for the high altar of Siena Cathedral in 1308 and the Rucellai Madonna for a chapel in Florence commissioned by the Compagnia del Laudesi di Maria Vergine. Although he gained infamy for his financial troubles, he was considered one of his generation’s most radical painters, influencing and attracting many pupils, including Master of Badia an Isola, Master of Città di Castello, Ugolina de Nerio, and many more (Robert et al., 1983). Duccio contributed substantially to the Gothic painting style through his formality of the Italo-Byzantine tradition. His most renowned works include Singers Praising the Virgin Mary, Madonna Recellai, and The Madonna of the Franciscans (Boskovits, 2016). His other surviving works include Configuration, Disputation with the Doctors, Christ before Caiaphas, Triptych: Crucifixion and Other Scenes (1302-08), and Dosale no. 28 (1305), among others. Sample of his works include:

Duccio di Buoninsegna

Maesta de Duccio ca. 1308-1311

Tampera and Gold on Wood

84 × 156 in

The Maesta (1311) forms the centerpiece of Siena Cathedral and shows Duccio’s specialization in religious depictions. It is argued that Pisani’s sculpture greatly inspired Duccio’s artwork.

Duccio di Buoninsegna

Madonna with Child ca. 1300

Tampera on Wood

11.0 × 8.3 in

Madonna with Child(1300) is inspired by the biblical story of Jesus Christ and his mother, Mary (Madonna), featuring Christ’s child gently pushing away the sorrowful mother’s veil whose expression betrays her foreknowledge of the impending crucifixion of the child.

Giotto di Bondone

Giotto was a late Middle Ages painter and architect credited for breaking the predominant Byzantine style and reintroducing near-to-life painting that had been abandoned and neglected for two hundred years (Vasari et al., 1998). Born in 1267 near Florence, a son of a humble blacksmith, he was discovered by the great Cimabue while painting a picture of his father’s sheep, so the legend goes. The legend further emphasizes his talent, stating that his painting was so lifelike that they confused even the most seasoned painter, including Cimabue. He eventually surpassed his mater with his works being praised within his lifetime, with Dante Alighieri writing, “Oh, the vein pride of human talents! Cimabue expected to retain the field, but now Giotto has the voice, and the other’s glory is lessened” (Barolini, 2014, p. 2). Throughout most of his young life, Giotto worked alongside his Master Cimabue. Several paintings bear the hallmarks of both Giotto and Cimabue, with speculation rife that Cimabue may have traveled with Giotto to paint the giant murals for the new Basilica in Assisi. Vasari notes that some of the earliest works by Giotto were commissioned by the Dominican monks of Santa Maria Novella, including the mural of the Annunciation and a five-meter-tall hanging crucifix.

He undertook his first major work in Assisi between 1290 and 1295 before traveling extensively in Italy and establishing studios in various localities where his work was replicated by his students, some of whom went ahead to launch their careers (Gardner & Giotto, 2011). On traveling to Padua, he set about painting his most well-known work, The Last Judgment (1306), at the Arena Chapel (Ruskin & Hewison, 2018). Between 1305 and 1315, he was commissioned by cardinals of Rome to create the mosaic of the façade of the Ancient Saint Peter’s Basilica; he was also contracted to the Church of Santa Croce in Florence and was also contracted by the Peruzzi to create two murals of John the Baptists and John the Evangelist(1315-1325) at the Peruzzi chapel, held in high regards by most renaissance artists. Other renowned works by Giotto include Ognissanti Madonna (1314-1327), Stefaneschi Triptych (1320-1330), Christ’s Lamentation (1304-1306) at the church of Santa Chiara, Illustrious Men on the Windows of Santa Barbara Chapel in the Castel Nuovo, Pentecost (1310-1318), Madonna and the Child (1320-1330) among others (Bondone, 2016). He passed on in January of 1337 and was laid to rest on the left side of the entrance to Florence Cathedral.

Selected works

Giotto di Bondone

Ognissanti Madonnaca. 1310

Tempera on panel

128 × 80 in

Ognissanti Madonna (1310) is based on traditional Christian imagery depicting the Virgin Mary seated on a throne with Christ’s child on her lap, surrounded from all sides by the saints. The painting is considered the first to move from the Byzantine style into the new Renaissance style while retaining some influences of Byzantine art infused with Gothic art forms.

Campanile di Giotto

1337-1359

Florence Cathedral, Florence, Italy

Campanile di Giotto (1337–1359) – The 84m free-standing structure stands adjacent to the Santa Maria de Fiore Basilica in Florence, Italy. It was initiated by Giotto in 1334 when he was appointed as the Master of works of the cathedral. Works on the structure were incomplete at his death, and his successor, Alfred Pisano, continued with the construction, introducing some changes to the overall structure. The structure bears the religious connotations typical of Giotto’s works, with several symbols observed, including the number seven and the Hexagonal panel reminiscent of the beginning of mechanical art, among others.

Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, famously known by the mononym Michelangelo, was a painter, sculptor, and architect born in 1475 in Caprese in the Republic of Florence in present-day Italy. Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci are considered the world’s foremost Renaissance artists; their paintings and sculptures bring some of the most revered works of art (Lazzeri et al., 2012). Unlike the other great artists of his time, his life is much better documented since three versions of his biography were published while he was still alive. His parents realized his interest in art early and sent him to apprentice with Ghirlandaio, where he learned the fresco technique. After that, he studied classical sculpture in the palace gardens of Lorenzo de Medici, granting him access to the elite crowd of Florence, interacting with the most prominent poets, learned humanists, and scholars, a combination of experience that laid the foundation of what would become his distinctive style – A combination of lyrical beauty and macular precision and reality (Vasari et al., 1998). After that, Michelangelo moved to Bologna and finally to Rome, where he worked for the rest of his life.

Michelangelo’s personality was characterized by brilliance and considerable talent punctuated by quick tempers and spells of melancholy. Some of his most outstanding works include Paintings – Creation of Adam (1512), Last Judgment (1541) and, Sistine Chapel (1508-1512); Sculptures – Pieta (1498-1499) and David (1501-1504); Architecture – the Tomb of Julius II (1505-1545), the design of the Medici Chapel and Laurentian Library in Florence and his crowning jewel, being selected to be the chief architect of the St. Peter Basilica (1546) in Rome (present-day Vatical city). He died following a brief illness aged 89 at his home in Macel de’Corvi in Rome and was laid to rest at the Basilica di Santa Croce. With multiple works of art credited to him, Michelangelo was and is celebrated as the epitome of humanist artistic expression in the Renaissance age as well as one of the most enduring artists in the world. His artwork continuously attracts vast numbers of visitors each year.

Selected works

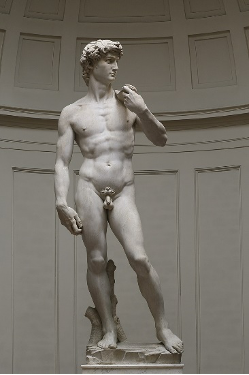

Michelangelo

David ca. 1501-1504

Marble sculpture

17 x 6.5 ft

David (1505) – The first of its kind in post-antiquity Florence, the David statute was commissioned as one of a series of biblical statutes to be placed at the Florence cathedral but was moved to a public square. Incidentally, despite Michelangelo’s relationship with the Medici family, the statute represented the defense of civil freedom threatened by the Medici family’s grip on power in Florence and the ever-present danger of invasion from powerful rivals.

Michelangelo

Madonna della Pietà ca. 1498-1499

Marble Sculpture

68.5 x 78.8 in

Madonna della Pieta (1499), known as Pieta, represents Jesus Christ and Mary at Mount Golgotha following his death on the cross. Inspired by Dante’s Devine Comedy, Michelangelo carved Jesus as visibly older than his mother. The image has an uncanny balance of classical beauty in the Renaissance infused with naturalism. The sculpture was initially commissioned for the funeral monument of the Cardinal of France but was moved back to its present location in the Vatican in the 18th century.

Leonardo da Vinci

Arguably one of the most, if not the most, famous artists, Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci, was born in 1452 in Vinci, Italy, to a low-class woman (Worrall, 2017). He studied under Andrea del Verrocchio in Florence before becoming an independent painter, being commissioned to paint the altarpiece of the Chapel of St. Bernard and The Adoration of the Magi (1482), neither of which he completed. After moving to Milan, he was commissioned to paint The Virgin of The Rock (1483-93) and The Last Supper (1495-98), and many other works; he also stayed in Rome in service of Leo X and on the occupation of Rome, went to France in service to King Francis I, both of whom held him in high esteem. He died in 1519 following a stroke, with legend stating that the King held his head as he died.

Leonardo is considered one of the greatest painters of the resistance age. He is credited with the foundation of a high renaissance, with some of his works being some of the most famous works of art in history and influencing numerous future Renaissance artists, including Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, better known as Raphael (1483-1520) who went ahead to form the trinity of great masters alongside da Vinci himself and Michelangelo (Clark et al., 1993). Some of the most renowned works of art fully credited or in Part to Leonardo da Vinci include the Mona Lisa (1503-1516)- one of the most famous paintings by da Vinci, Salvator Mundi (1599-1510), the Vitruvian Man (1483)

Leonardo da Vinci

The Mona Lisa (1503-1506)

Oil on Lombardi Poplar Panel

30.2 x 20.9 in

The Mona Lisa (1506) is a half-length portrait painting of the Noblewoman Lisa Del Giocondo by da Vinci. It remains one of the most well-known and valuable paintings in the world. The dominating feature of the image is how alive the woman looks, with her gaze fixed directly on the observer with a background featuring aerial perspective receding to an icy landscape and the horizon in line with the subject’s eyes (Zollner, 2006).

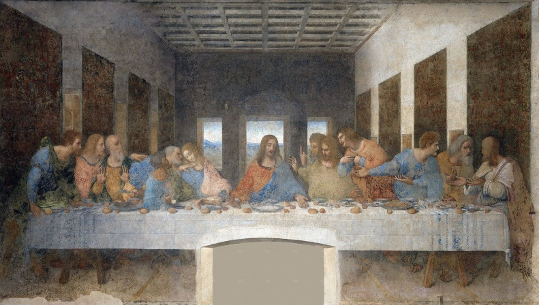

Leonardo da Vinci

The Last Supper ca. 1495-98

Tampera on gesso, pitch and mastic

180 x 350 in

The Last Supper (1495-98) painting depicts Jesus and his disciples during the last supper, specifically when he announces that one will betray him. It continues Leonardo da Vinci’s religious depiction with this one commissioned by the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza. It was painted on materials that allowed for alterations and revisions and became one of the most extensive works by Leonardo (Vasari et al., 1998).

Parmigianino

Born Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola in 1503 in Parma, Italy, Parmigianino was well known for the refined sensuality in his paintings, becoming one of the most prominent mannerist period artists (Hartt & Wilkins, 2003). He aspired to follow in the steps of other great artists, such as Raphael, and thus moved to Rome, the center of art and culture, to pursue this dream. However, his dream was cut short in 1527 by the invasion of Rome by the German army, and he had to flee back to Parma, where his fame continued to grow, gaining recognition and celebration. However, his career suffered when his obsession with alchemy and eccentricity interrupted his works and earned him a jail sentence for failing to uphold a contract, signaling the beginning of the steady decline of his artwork till his death from fever in 1540.

Parmigianino’s works were styled as elegance of his decorations, freedom of the brushstrokes, and subtle elongation of human features in his painting as illustrated in The Vision of St. Jerome (1527); his religious scenes displayed grace and sensuality with more emphasis on the artificial expression of nature, a departure from Raphael’s idealized classical beauty. Most art scholars agree that the expression of these styles implicated a feeling of deep spiritual uncertainty and an attempt to fulfill deep-rooted etching, which he eventually expressed through an interest in alchemy. His drawings are notable for the juxtaposition of high Renaissance art expression – as done by Raphael – and the mannerist artificial expression (Artble, 2023). His most notable works are; the Portrait of a Collector (1523), the Madonna and Child with Saints (1527), and the Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine (1531), among others (Ekserdjian, 2006).

Selected works

Parmigianino

Madonna dal collo lungo ca. 1535-1540

Oil on Panel

135 × 59 in

Madonna dal collo lungo (1535-1540) The painting depicts Madonna and the child with angels. It was commissioned for the funeral chapel of Francesco Tagliaferi but remained incomplete on the death of Parmigianino. It features distorted images of Mary with an unusually long neck, and Christ is much bigger than a normal baby.

Parmigianino

Madonna and Long Child with Angels and St. Jerome ca. 1535-1540

Oil on Wood

85 × 52 in

Maria Bufalini commissioned the vision of St. Jerome (1540) to decorate the family chapel at Santa Salvatore Church in Lauro. It features St. Jerome sleeping next to a crucifix receiving a vision of St. John the Baptist pointed at a mother and child representing Mary and her son Jesus Christ. The image of John pointing upward is reminiscent of da Vinci’s John the Baptist.

Gustave Courbet

Jean Désiré Gustave Courbet, born in 1819 in Ornan, France, was one of the leading figures of the realist movement of the 19th century, rejecting the romanticism and academic convention so revered by the previous generation of visual artists. His independence from the establishment and socialist politics set him on a clashing course with the French authorities leading to his subsequent imprisonment and exile in Switzerland, where he died in 1877, aged 58 (Riat, 2012). Gustave’s art was in the realism era and faced. His primary source of inspiration was his own experiences and those of others, abandoning the long-established artistic traditions of presenting historical figures rather than courting controversy by expressing social concerns in his works. Unlike artists before him, Courbet drew most of his paintings based on the real-life experiences of the poor and the lowly. He addressed the rejection of his works by established exhibitions and art critics through his works, The Artist’s Studio (1855) (Masanes, 2006).

Courbet’s notoriety continued with The Young Ladies on the Bank of the Seine(1856), which received mass condemnation from art critics for displaying prostitutes with their undergarments exposed, a taboo in neoclassic art (Courbet, 1856). This uproar did not deter him; in fact, he went ahead and painted other controversial works, including; The Village Damsels (1852) and The Wrestlers (1853), Femme Nue Couchee (1862), L’Origine du Monde (1866), and Sleep (1866).

Selected works

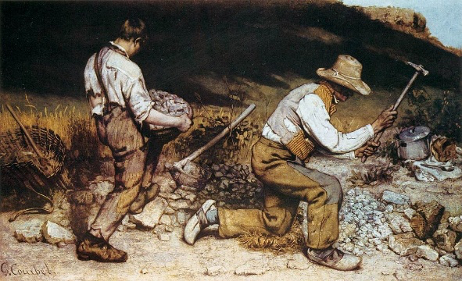

Gustave Courbet

The Stone Breakers ca. 1849

Oil on Canvas

65 × 94 in

On the Stone Breakers (1849), Courbet features two men he had encountered undertaking hard labor on the roadside on his way back to Ornan in 1848. In the painting, he avoided idealizing the models as the norm, preferring to show them in their realities. The historical timelines of his life and socialist-leaning also drove him to paint the simple man in his natural environment to counter the establishment (Savatier, 2006).

Gustave Courbet

A Burial at Ornan ca.1850-51

Oil on Canvas

142 × 235 in

On A Burial at Ornan (1850-51), Courbet exhibits the burial of his uncle, with the attendees being the models of this work, unlike in classical and neoclassic works where the characters presented were hired actors, thus drawing both criticism and praise in equal measure.

Drawing from his characterization as a genius and a savage, Courbet courted even more dissension through works such as The Bathers (1853). His main source of inspiration from the realities and suffering around him, especially the commoner’s plight. In a departure from the previous artists, his works were more original, uncompromising, full of social context, and highly divisive. His works were enigmatic, a transformation from the old traditional art often commissioned by the church, the nobles, or the aristocrats of his time, a humanistic form of art. He set out to challenge the establishment through his works and politics. He thus prepared the way, alongside Cezanne, for cubism, an art form that combined multiple perspectives to present context (Metzinger, 1910).

Comparison of the Artists

The differences between these six artists are glaring, primarily due to their living in different periods and their differing circumstances of their lives. However, the similarities are uncanny as most artists influenced each other, with the previous generation influencing and impacting the upcoming generation. This similarity is seen through their biographies, works, relationships, and inspirations.

Similarities

The most remarkable similarity between all six artists was their pioneering in different timelines. While Duccio introduced an element of softness in the prevailing Byzantine painting style, Giotto introduced natural humanistic elements which had laid dormant for several years. Michelangelo reinforced humanistic ideas in his paintings and sculpture with an emphasis on muscular precision and lyrical beauty admired by most, while his nemesis Leonardo da Vinci is credited with the foundation of high Renaissance art and using his talent to invent several items (Clark et al., 1993). Parmigianino introduced elegance and natural beauty, which departed from the classical beauty so common with the artists during his time (Artble, 2023), like Raphael, while Courbet introduced social awareness and a departure from the religious basis of painting to the point of being banished by some major exhibitions. All in all, each of these writers was a master of a new art form, for which they created or improved. No one can question the ingenuity and talent of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, or even Courbet, and their works continue to inspire new art enthusiasts (Garg, n.d.). Analyzing their works and biographies indicated their dedication to their art. Vasari, in his anthology, considers them masters of the art, and over the entire period reviewed, each one of these artists has grown in fame, influence, and stature (Vasari et al., 1998). This fact can only lend credence to their prowess.

Differences

The main difference between these masters and art is their source of inspiration. While most of the paintings depicted above were religious, others, like Courbet’s, were inspired by reality, and he outrightly shunned classical painting. Equally for Parmigianino, his paintings display spiritual expression and not in the traditional sense, and analysis of his works has indicated an attempt to express his eccentric thoughts through his works. In a nutshell, each of these artists had their specific inspiration based on their experiences, mental state, politics, and prevailing social and artistic structure, which played a big part in the expressions in their works.

Conclusion

Art has always been a means for human expression, with each era of human civilization presenting its idea in various art forms. While this is a global phenomenon, nowhere is this clear than in Europe. Since antiquity, Europe and especially southern Europe, has been the center of culture and commerce, with art becoming the best form for expressing one’s success and, therefore, a high demand for talented artists who can satisfy the demand for this trade (H. W. Janson, 2001). Therefore, it is notable that most prominent artists trace their roots to Europe and Mediterranean Europe, with Italy and Florence home to some of the most reputable artists (Artsy Editorial, 2014; HistoryWorld, 2012). This essay goes into the lives of some artists, their works, inspirations, schools of thought, and their influence in the present world. In doing so, a glaring observation is noted, while these artists lived in different timelines and countries, they have more similarities than differences.

References

Arable. (2023). Parmigianino Style and Technique | artble.com. Artble.Com. https://www.artble.com/artists/parmigianino/more_information/style_and_technique

Artsy Editorial. (2014, March 25). Italian Art History, in a Nutshell. Artsy. https://www.artsy.net/article/editorial-italian-art-history-in-a-nutshell

Barolini, T. (2014). Purgatorio 11: After 1000 Years?. In Commento Baroliniano. Columbia University Press. https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/purgatorio/purgatorio-11/

Bondone, G. di. (2016). Delphi Complete Works of Giotto. https://www.scribd.com/book/306353776/Delphi-Complete-Works-of-Giotto-Illustrated

Clark, K., Leonardo, da V., & Kemp, M. (1993). Leonardo da Vinci. Penguin Books.

Courbet, G. (1856). Young Ladies on the Banks of the Seine (Summer) | NG6355 | National Gallery, London. The National Gallery. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/possibly-after-gustave-courbet-young-ladies-on-the-banks-of-the-seine-summer

Gardner, J., & Giotto, 1266–1337. (2011). Giotto and his publics : three paradigms of patronage. Harvard University Press. https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674050808

Garg, A. (n.d.). Renaissance Art Garg.

Hartt, F., & Wilkins, D. G. (2003). History of Italian Renaissance art : painting, sculpture, architecture. H.N. Abrams.

HistoryWorld. (2012). Timeline: Italian art. HistoryWorld. https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780191736520.timeline.0001;jsessionid=8DF40ACCE714A2C26E5EB12A5D41FD82

Janson, H. W. (2001). History Of Art (A. Janson (Ed.)).

Lazzeri, D., Huemer, G. M., Larcher, L., & Agostini, T. (2012). Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery, 130(3), 492e-493e. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e31825dc536

Livni, E. (2018, February 13). Art made Homo sapiens smarter than Neanderthals—and better equipped to survive. Quartz. https://qz.com/1205270/art-made-homo-sapiens-smarter-than-neanderthals-and-better-equipped-to-survive

Masanes, F. (2006). Gustave Courbet 1819-1877: The Last of the Romantics. http://www.amazon.fr/dp/3822856835

Metzinger, J. (1910). Note sur la peinture (Vol. 9). http://www.peterbrooke.org/form-and-history/cubisme/note.html

Robert, P., Bergman, M., Bush, V. L., Peckar, R. S., Gray, M. C., Katzoff, N. M., Mitchell, L. H., Mitchell, P. M., Rouse, H. C., & Seitz, E. J. (1983). Rutgers Art Review: Vol. IV (T. Somma (Ed.)). Howard Press.

Ruskin, J., & Hewison, R. (2018). Giotto and his works in Padua. David Zwirner Books.

Savatier, T. (2006). L ’ origine du monde : histoire d ’ un tableau de Gustave Courbet La revue de presse La revue de presse. 1–5.

Vasari, G., Bondanella, J. C., & Bondanella, P. E. (1998). Lives of the Artists (Oxford World’s Classics). 586.

Zollner, F. (2006). Leonardo ’ s Portrait of Mona Lisa del Giocondo (Vol. 138).

write

write