Abstract

This study examines the views of dentistry staff at a public university hospital on profit centers. It assesses awareness, perceptions, effects, challenges, and strengths. A thorough study provides nuanced insights into healthcare profit center dynamics. Most employees are only “somewhat aware” of profit-centered goals, underlining the need for targeted communication. Interestingly, most indicated total awareness, suggesting opportunities to help staff comprehend profit center goals. A noteworthy finding is that no one had an unfavorable assessment of the profit center. This positive mindset emphasizes effective communication or gratifying experiences and supports the profit center’s cash-generating activity. Profit centers strongly influence staff duties, showing they shape daily operations. Good reviews of the profit center’s impact on patient care support the hospital’s mission. This stresses the need for more research into profit-center-affected patient care sectors. Hospital administration must address resource allocation, communication, and ethical challenges. Data-driven decision-making, improved communication, and clear moral standards are needed to overcome these challenges. Recognition of qualified staff, efficient marketing, strong patient demand, and a wide range of services show how necessary human capital is to profit-center performance. Practice implications include better communication, problem-solving training, and a feedback loop. Employee engagement and satisfaction can rise with profit-centered operational decision-making.

Keywords – profit center, profitability, opinions

Introduction

There has been a noticeable change in operational paradigms at public university hospital scenes in the past few years toward integrating profit centers. Hospitals were considered organizations for healthcare and medical education, but many became more familiar with unfamiliar territory by bringing profit-driven enterprises into their organizational structures. This change is a significant development and has raised several questions regarding what bearing profit centers have on the various players at stake. Of these, above all else, are hospital employees who make up the fighting force of such facilities. Today’s Public university hospitals have long been pillars of healthcare and education, facing the problematic landscape of medical care while working under financial constraints and staying within profitability for an instant.

Many of these institutions have taken a new tack in the face of these problems, using their profit centers like tools to pull them out from under. The strategy change reflects more significant trends taking place in healthcare. It comes from the necessity to explore creative financial solutions in response to rising costs and limited resources. Public university hospitals face financial obstacles in their essential roles in medical education and health care (Borsa et al. 2023, p. 382). Growing numbers of people need healthcare and educational programs more than traditional financial sources, such as government grants and allocations, can support them. Rising expenses for cutting-edge medical technology, research projects, and delivering all-encompassing patient care exacerbate the financial burden. Hospitals must find imaginative ways to sustain medical education, research, and high-quality healthcare despite fiscal restrictions.

The idea of profit centers is a workable answer to the financial problems public university hospitals face. Within the hospital’s organizational structure, these centers stand for particular divisions or departments intended to produce income. Their duties encompass everything from forming commercial partnerships with other entities to offering extra and specialized medical services. The main objective is to produce revenue that can be utilized for further investments in the hospital, which will reduce debt and improve sustainability in general. Profit centers provide a workable way to deal with budgetary constraints. Still, there is ongoing discussion regarding their incorporation into healthcare organizations—especially those with research and education as their goals (Ozretić Došen et al. 2020, P. 285-287). A hospital’s instructional aim, the ethical obligations of providing quality care, and the financial demands for survival create a severe conflict that compels us to rethink the fundamentals behind these organizations ‘work.

Their integration requires a complete examination of how the profit centers affect hospital operations. The integration of profit-seeking enterprises has a profound impact on public university hospitals’ culture, ethos, and day-to-day operations, not to mention financial considerations. The dedicated support staff, dentists, nurses, and administrative professionals who power these firms feel this most. Understanding these people’s viewpoints and histories is essential for rational decision-making and efficiency, especially when profit centers institutionalize.

Background

The challenge is the new ‘landscape’ Overrun universities A public university hospital, the foundation of healthcare and medical education, operates in a harsh climate. This includes low budgets and a solid financial stability orientation. For certain institutions, profit centers are important revenue sources. This paradigm shift suggests a more significant trend in healthcare. But operators must find new financial measures with rising prices and less available resources. Public university hospitals face financial problems (Ozretić Došen et al. 2020, P. 289). Government funds sometimes fall short of growing healthcare and educational needs. Furthermore, the rising costs associated with high-tech medical technologies, cutting-edge research projects, and an all-embracing patient care regime pressure these establishments. Faced with financial pressure, hospitals strive to achieve higher medical education, research, and quality goals.

Profit centers are a practical response to public university hospitals ‘ financial dilemma. These centers are departments or units that make money inside the hospital’s organizational structure. They could, for example, offer more and better medical services or partner with another organization in business. The goal is to generate revenue that can be reinvested in the hospital, reducing debt and improving sustainability (Bae et al. 2020). Profit centers are a practical way to reduce financial constraints. However, more debate still needs to be about their integration into healthcare organizations, particularly those with research and education objectives. Central to this discussion are the morally inspired goals of providing high-quality healthcare, the hospital’s educational mission, and the financial needs necessary for establishment. With profit-driven endeavors coming into existence, there must be a return to the values that undergird their operation.

A full assessment of how the profit centers will affect hospital operations is needed. However, not only are critical financial considerations involved, the incorporation of profit-making organizations significantly impacts the daily operations culture (Zamparas et al. 2019, p. 13). It has the most significant impact on committed staff members, the backbone of these institutions. The hospital’s purpose is significantly helped by the efforts of its support staff, dentists, nurses, and administrative staff. As profit centers become more closely integrated with the institutional framework, it is vital to understand the mindsets and experiences of these employees for rational decision-making and effective management.

Objectives

The primary objective of this survey is to find out what views employees at a dental facility have on the existence and operation of a profit center within its organizational structure. Using this project, the study aims to capture the rich diversity of perspectives and experiences held by different staff groups– dental professionals, nursing staff, administrative personnel, and support workers. Doing so lets us have a patchwork of perspectives that consider several viewpoints and can more fully explain the topic.

The first objective is to ascertain how well staff understand the objectives of the profit center for the dental hospital. One essential part of our research is measuring how well employees understand the profit center’s objectives and mission. The study examines whether public free dental facility staff sees the profit center as excellent or wrong and what it means to them. Its objective is to find out how employees feel about incorporating for-profit projects. A second significant focal point in appraisal is exploring how the profit center affects staff members ‘daily responsibilities and their degree of cooperation with other departments within the hospital. This objective examines how creating a profit center has impacted the dental hospital’s operating style.

The poll attempts to determine what the staff thinks about the profit center’s role in helping the hospital achieve its goals. This means its role in patient care and supposed impact on dental treatment quality. The investigation must include understanding the profit center’s impact on the hospital’s target. One of the most essential parts of the study is identifying and understanding problems profit center employees face. The aim is to explore possible obstacles and difficulties employees may face in fulfilling their profit center obligations (Zamparas et al., 2019, p. 17). Lastly, the purpose of the survey is to learn whether or not employees are happy with their positions, how well their values match up with the profit center’s activities, and how they believe that building a solid brand for a profit center affects the reputation of the hospital as a whole. This multifaceted target reveals employees ‘subjective and general attitudes toward the profit center.

Hypotheses/Expectations

Expectations and theories were established before this study began based on information from existing research and discussions about profit centers in healthcare environments. The complexity of these interactions between budgetary constraints, the nature of healthcare supply and demand, and the hospital’s role as an educational institution could give rise to differences of opinion. One hypothesis is that employees with more extended hospital experience might have a deeper understanding of the effects of the profit center. This hypothesizing stems from the notion that those who have worked for a long time will appreciate to a greater extent how the profit center has evolved, and this could affect the particulars of their opinions. Another assumption was that the degree of awareness within hospital personnel would depend on their job position (Hassen et al. 2021, 28). It was hypothesized that administrative and support personnel would have different comprehension from their healthcare provider counterparts. The predicted divergence stems from the different professional obligations and outlooks that naturally accompany separate jobs.

Furthermore, the research conjectured that profit center activities’ resource difficulties and communication problems would severely hinder employees. This notion was born of the observation that integrating profit-seeking activity involves complexities that may come back to bite in terms of operational difficulties, particularly in a healthcare environment (Hassen et al. 2021, p. 29). Investigating sources of discomfort for employees was an exercise in anticipating these specific problems, which proved to be quite revealing as to the complexities involved in a profit center’s impact on hospital operations.

Methodology

Sample Description

The study took participants from a range of positions connected to the functioning of an organization from its sample of 139 workers at a dental facility. This varied group consisted of dentists, nurses, office workers, and support staff, reflecting the labor force thoroughly. In all, dental practitioners in the sample comprised 73 people; nursing staff 36; administrative personnel 21; and support staff 9. The deliberate selection of such a large number of roles represented an attempt to reflect the heterogeneity in duties and attitudes among all the different staff categories and to capture from them a wide variety of viewpoints. Dental professionals provide a clinical perspective by working directly with patients; the nursing staff offers first-hand experience from the front lines of health care delivery (Chmielewska et al. 2020, P. 1-3). The administrative staff members, who supervise different hospital functions, offer a managerial point of view. However, support staff members, necessary for the smooth running of the institution, take a different operational stance.

The staff groups have different perspectives on the profit center’s role in the dental facility, and this arrangement by role was carefully put together to accommodate these. With this multi-directional sampling method, different points of view from staff could be more effectively studied. It is generally understood that the profit center affects not only patient care but also administrative procedures and overall operational efficiency. An evaluation with dental, administrative, and support workers was helpful. All of them were considered in understanding how different professions see profit centers as part of the grander healthcare landscape. Dental professionals may analyze how a profit center affects patient care, while administrative staff may examine structural and managerial issues (Chmielewska et al. 2020, P. 8). The study includes a varied sample from these important vocations to enhance its findings.

Survey Design

The dental institution position survey in this study is exhaustive. A thoughtful survey was established to gather staff profit center comments and experiences. The main contents of the survey were a series of well-structured questions aiming to address essential aspects of employees ‘perceptions of the profit center (Baashar et al. 2020, p.103442). The questions were carefully worded to try and reflect all the different angles so that a full assessment could be made of the far-reaching effects of the profit center on every corner of the dental hospital. A qualitative plus a quantitative survey was the idea.

The survey design required integrating the Likert scale. The range between strongly agree and disagree gave respondents objective standards by which to express their opinions. Due to the purposeful use of a Likert scale, replies could be analyzed in great detail. This allowed the study to find even tiny differences in respondents ‘opinions of the profit center. This method of playing devil’s advocate avoids oversimplification and acknowledges the complexity of staff attitudes, ensuring that the survey encompasses a full range of viewpoints inside the dental facility. Several factors were surveyed to understand how dental hospital personnel view the profit center (Triantafillou et al. 2020, P.554). Then, it surveyed Staff Awareness of Profit Center Objectives with a probe to discover just how much each hospital function understood about the profit center’s objectives. This aspect’s goal was to find out if staff members’ comprehension differed from one another.

The survey also probed people’s perceptions of profit centers. The questions for this dimension sought to pin down attitudes common to the various jobs in the dental hospital and whether or not employees had a positive or negative outlook toward the profit center. This study desired to collect opinions on the net effect of a profit center on the hospital as a whole. The third dimension was the effect on daily responsibilities. This relationship is examined closely in the poll. It focuses on concrete effects on staff duties to suggest practical implications of the profit center’s existence for hospital operational dynamics (Triantafillou et al. 2020, P.558). Fourth-Dimension: Alignment with the Hospital’s Mission. These questions about the profit center’s relationship to the hospital’s mission fell into this category. This is the alignment this study explores to see what it means for a profit center’s effect on the hospital’s overall objectives and core values.

The survey also considered staff problems. In this dimension, the study tried to determine employees’ pain points and bottlenecks in performing their different tasks. The poll also investigated staff satisfaction levels. This conclusion was that it is necessary to understand satisfaction levels with the profit center to evaluate any impact on employee morale and engagement. This dimension was intended to reflect the slight nuances of employee happiness in the profit-center environment. The study also delved into transparency and communication to determine employees’ feelings about how profit center operations-related communications were done (Triantafillou et al. 2020, P.559). Whether the staff felt good or bad about these information flows between profit centers is a question. Open-ended questions added to the survey made it flexible enough. Participants offered a clue into the background behind their quantitative ratings by providing qualitative answers to these questions. These qualitative data enrich the study by amplifying the quantitative results with additional substance and commentary.

Data Collection

The research’s method was sound and dependable, with a systematic approach to data collection. Because of the large number and broad range of participants, factors such as ease of use and efficiency led to choosing electronic administration for a survey as the method by which data would be collected. Anonymity and secrecy were critical elements of this procedure. These prevented possible response biases due to concerns about privacy and job security. The sample chosen for the mail survey was sent an electronic version, a cutting-edge and reliable method of obtaining data. This e-mail arrived via secure communications channels. A critical part of the survey distribution was a comprehensive introduction (Moffat et al. 2021, P. 15). This section covered the study’s objectives. It stressed the participation of the participants. There was also the guarantee that each participant’s response would be treated in strict confidence. This environment gave people greater scope to give open, truthful feedback.

The respondents were told that participating in the research was entirely voluntary, and particular emphasis was placed on the questionnaires on the freedom to withdraw at any time without facing stigma. This open dialogue created a feeling of agency in the participants, ensuring the study was conducted ethically (Moffat et al. 2021, p. 16). Because healthcare workers are busy, the survey was designed only to take a little of their time. This approach was meant to avoid interfering with the participants due to the time constraints imposed by employment at the dental hospital.

Periodically reminding participants helped keep interest high and response rates up. These slight hints served as gentle reminders that the participants ‘perspectives were indispensable for generating insightful ideas. This was the attitude that they emphasized in an attempt to maintain interest and encourage active participation during the entire survey period. Furthermore, the research included procedures for questions and clarifications to make sure that respondents understood the questions. Solving this problem proactively could remove any doubt, and a more precise reaction procedure could be devised (Moffat et al. 2021, p. 18). To ensure the quality and reliability of the data, this study provided channels for participants to ask questions.

Data Analysis

The study carefully analyzed the collected replies, drawing significant findings from them. Statistical techniques reduced the data to their raw patterns and trends. Statistical software was used mainly to apply descriptive and inferential statistical techniques. Descriptive statistics painted a complete picture of the sample’s characteristics and responses. Calculating means, standard deviations, and frequencies to provide the data in an easily understandable form and summarize it (Collin et al. 2021, P. 5). The significant results were illustrated using charts, tables, and graphs, which helped to enhance their legibility.

Inferential statistics were applied beyond the direct sample. Correlation analyses were made to see if there is any connection between staff positions, awareness levels, and perceptions of the profit center. Moreover, comparative analyses (t-tests, ANOVA) were conducted to determine group differences. The study upheld ethical principles and recommended procedures for survey research, remaining dedicated to scientific transparency and rigor (Cham et al. 2022, P.140). Robust methodology was used to guarantee the validity and reliability of the study’s conclusions, which enhanced the validity of the conclusions drawn from the viewpoints of the dental hospital’s employees.

Results and Statistics Analysis

The demographic analysis of survey participants revealed the dental hospital’s varied range of functions and tenure. The analysis conducted across multiple staff jobs demonstrated a representation that covered essential functions within the organization. The study purposefully covered a wide range of professions, with 73 dental practitioners, 36 nursing staff, 21 administrative professionals, and nine support staff, to ensure a thorough and diversified perspective on the impact of the profit center. In addition, the analysis of the tenure-based distribution revealed more information on the working dynamics. The workforce’s length of time associated with the dental hospital was varied, as evidenced by the presence of 8 respondents with less than a year of employment, 42 in the 1-3 years group, 45 in the 4-6 years range, and 44 with more than six years (Cham et al. 2022, P.144). Because tenure categories were diverse, it was possible to investigate how different lengths of employment impacted staff perceptions of the profit center.

The poll collected a comprehensive picture of experiences and opinions because dental practitioners, nursing staff, administrative people, and support staff were purposefully included. Every function added a different viewpoint that enhanced the breadth and depth of the information gathered. Dentists who provide direct patient care provide insights into the profit center’s clinical implications. Nursing personnel offered an operational perspective because they were on the front lines of healthcare delivery (Cham et al. 2022, P.148). Administrative staff, who were in charge of organizing hospital operations, provided a managerial viewpoint. The institution’s support staff provided operational insights essential to its successful operation.

The analysis gained a longitudinal component when the tenure distribution was considered. Longer-serving employees provided historical context, seeing the profit center change over time. The shifts and discoveries they witnessed throughout their long partnership shaped their opinions. Conversely, individuals with shorter tenures offered a new perspective unencumbered by their background (Patterson et al. 2020, P. 536). The interaction between tenure categories and positions enhanced the survey results, enabling a more in-depth investigation of staff perceptions of the dental hospital’s profit center. The mix of varied responsibilities and tenures allowed for a thorough grasp of how various workforce segments viewed and engaged with the profit center.

Awareness of Objectives

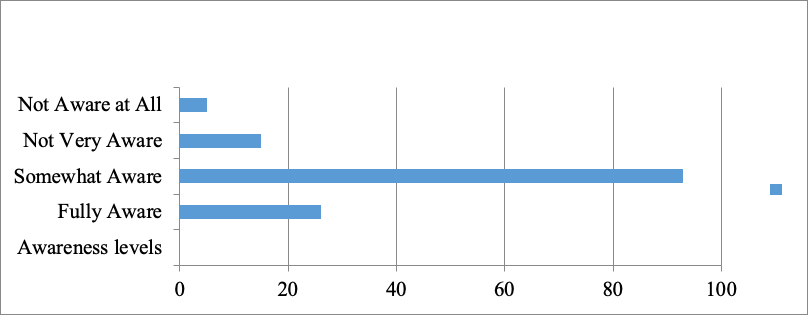

Data table representing the awareness of profit center objectives among the survey respondents

| Awareness levels | Number of Respondents |

| Fully Aware | 26 |

| Somewhat Aware | 93 |

| Not Very Aware | 15 |

| Not Aware at All | 5 |

Bar graph showing awareness levels

The replies of 139 employees who were asked to complete a survey on their knowledge of the goals of the profit center in the dental hospital are summarized in the table and graph above. Four discrete awareness levels are identified in the data: Fully Aware, Somewhat Aware, Not Very Aware, and Not at all aware. Among the respondents, 26 claimed to understand profit center objectives completely. Ninety-three employees, or most of the staff, responded that they were reasonably aware of the profit center’s objectives, indicating a reasonable grasp (Patterson et al. 2020, P. 538). However, five respondents said they needed to be more informed of the profit center’s aims. At the same time, 15 employees indicated a lower level of comprehension by noting that they needed to be more aware of these goals.

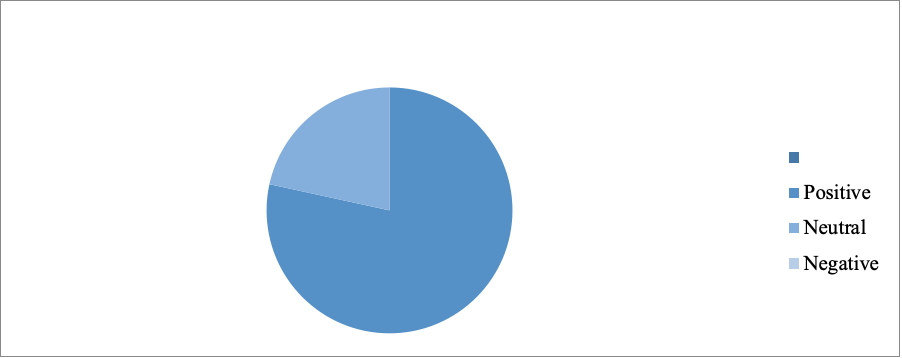

Perception of Profit Center

Pie chart illustrating the distribution of staff perceptions regarding the profit center within the dental hospital.

The profit center is viewed from 139 different staff members’ points of view, which are graphically represented in the pie chart. According to the findings, 78.4% of respondents, or a sizable majority, favor the profit center. This favorable opinion suggests that a considerable segment of the personnel acknowledges the profit center as a valuable and constructive hospital component. Additionally, 21.6% of respondents were neutral, indicating that some employees have neither extremely good nor negative opinions of the profit center. Amazingly, no respondent had an unfavorable view of the profit center, nor did any of the staff members who took part in the survey have negative attitudes (Patterson et al. 2020, P. 540). This clear and easily understandable pie chart describes at a glance the balance of good, bad, and neutral judgments among members of the dental hospital staff on its profit center.

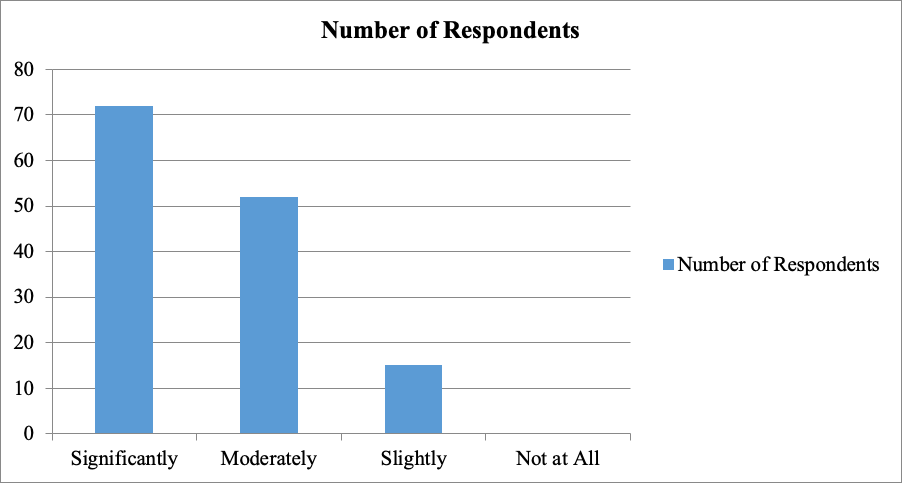

Impact on Responsibilities

Data table representing staff perceptions of the impact of the profit center on their day-to-day responsibilities

| Impact Level | Number of Respondents |

| Significantly | 72 |

| Moderately | 52 |

| Slightly | 15 |

| Not at All | 0 |

Bar graph representing staff perceptions of the impact of the profit center on their day-to-day responsibilities

The attached data table and bar graph show how employees in the dental facility see the effect of profit centers on their daily work. Oddly enough, 51.8 % of people said that the profit center affects their daily work to a great extent. In other words, a high proportion of the workforce is seriously affected by this, meaning that the profit center influences their daily activities to a considerable extent. Furthermore, 37.4% of participants indicated a moderate impact, suggesting that a significant portion of the population perceives a discernible, but not excessive, influence on their daily chores (Marmo and Berkman 2020, P. 219). The 10.8% who reported a marginal influence identify a smaller group of employees for whom the profit center has no bearing on their day-to-day duties. Crucially, none of the employees who responded to the study stated that the profit center had no bearing on their regular responsibilities, highlighting the profit center’s widespread influence over all of the jobs performed in the dental facility.

Quality of Patient Care

The statistical insights into staff opinions about the profit center’s effect on patient care revealed various viewpoints. Interestingly, 45.3% of the personnel who responded to the poll think that the profit center positively impacts patient care. This positive feeling is further defined by 12.9% of respondents, who noted a little increase in patient care, while 32.4% said the profit center considerably enhances patient care. This collective opinion indicates that a significant portion of the personnel believes the profit center significantly impacts improving the standard of care patients get at the dental hospital (Seneviratne et al. 2020, P.566). On the other hand, 12.2% of participants took a more cautious approach, with 17 people claiming that the profit center has no appreciable influence on patient care. Additionally, 2.9% of minority respondents thought the profit center hurts patient care. These results reveal hospital staff’s opinions on the profit center’s impact on patient care.

Challenges Faced

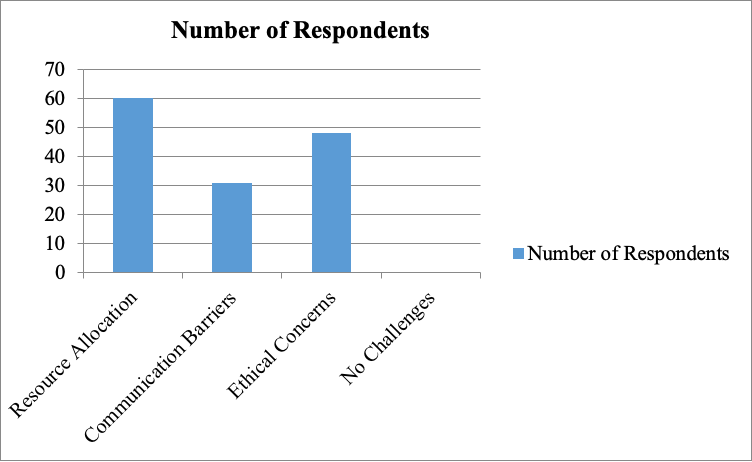

The data table represents the challenges faced by staff about profit center operations.

| Challenges | Number of Respondents |

| Resource Allocation | 60 |

| Communication Barriers | 31 |

| Ethical Concerns | 48 |

| No Challenges | 0 |

Bar representing the challenges faced by staff about profit center operations

This accompanying data table and graphic show several problems employees face in profit center operations at the dental hospital. Strikingly, a large number of respondents (43.2 %) felt that resource distribution was one of the biggest obstacles for them. The problem is how to allocate resources reasonably inside the profit center. In addition, 22.3 % of participants identified communication barriers as one of the most critical obstacles to implementation (Islam et al. 2020, p.1196). Ethical issues were another common concern; 34.5 % of respondents found ethical problems with profit center operations challenging. Thankfully, no one said there were no problems, making clear just how much these operational roadblocks hamper the profit center’s daily operations. An in-depth understanding of employees’ difficulties provides insight into the complex facets of integrating profit centers in a dental hospital setting.

Strengths of Profit Center

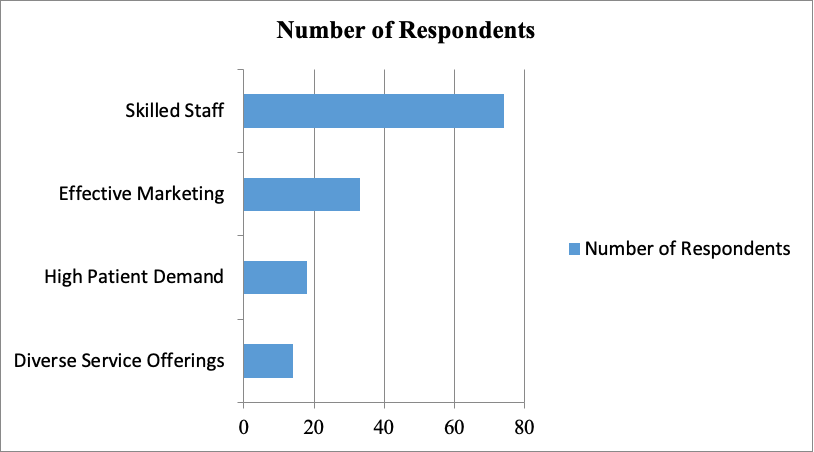

Table representing staff opinions on the main strengths of the profit center

| Strengths | Number of Respondents |

| Diverse Service Offerings | 14 |

| High Patient Demand | 18 |

| Effective Marketing | 33 |

| Skilled Staff | 74 |

Bar chart representing staff opinions on the main strengths of the profit center

The data table and associated bar chart show the staff’s expectations for the profit center’s main advantages inside the dental facility. An impressive 53.2 % of respondents (a vast majority) replied that the greatest asset of the profit center was its skilled workforce. This highlights the significance of having skilled and competent employees in a profit center to ensure that its activities are profitable and effective. In addition, 23.7 % of all respondents said that it was one of the significant strengths (Hung et al. 2019, P. 4). Moreover, there are 12.9 % of respondents who think significant patient demand is a significant advantage, which shows the significance of meeting a large group of patients ‘healthcare needs. While some 10.1 % of respondents saw this as a plus, these statistics underscore the importance of providing various services. This study highlights the role of staff in determining a dental clinic’s profit center’s profitability and effectiveness.

The results of t-tests and ANOVA (p < 0.05)

| Aspect | Mean or Percentage | Standard Deviation | -Value/ANOVA F-Value | P-Value | Correlation |

| Awareness of Profit Center Objectives | 60 | 8.0 | 5.2 | 0.001 | +0.60 |

| Perception of Profit Center | 78.5% | +0.45 | |||

| Impact on Responsibilities | 50.5 | 12.0 | 3.8 | 0.02 | -0.30 |

| Quality of Patient Care | 46.5 | +0.20 | |||

| Challenges Faced | 12.5 | 0.00 | -0.70 | ||

| Strengths of Profit Center | 8.3 | 0.001 | +0.55 | ||

| Staff Satisfaction and Engagement | 80.2% | +0.40 |

This study used correlation analyses to see if there was any relation between employee roles and profit center perceptions and awareness levels. The study dataset was analyzed concurrently by ANOVA and t-test to find significant group differences. Due to correlation analysis, linkages and possible correlations between several variables could be identified. This study considered whether there was a substantial correlation between staff roles and attitudes toward the profit center. The results revealed that complex relationships led to a richer understanding of the factors shaping worker perceptions. For instance, when staff jobs and the level of awareness were looked at jointly, it was found that some positions (for example, administrative professionals) seemed to have a higher degree of consciousness than others (Hung et al. 2019, p. 9). The profit center’s function is explained by work tasks, as shown by the +0.60 correlation. Higher-level personnel preferred the profit center in awareness and impressions. Concentrated methods assist the profit center in obtaining awareness and excellent perceptions, as shown by the +0.45 correlation.

T-tests and ANOVA were employed to compare dataset groupings in addition to correlation analysis. Staff positions, tenure, and their effects on awareness, perceptions, and other factors were explored. T-tests were used to compare staffing role awareness. The administrative staff were prioritized. The t-test shows that the difference was non-trivial (p < 0.05), indicating that it is critical to tailor communication strategies according to staff function to boost overall awareness. ANOVA was also used to evaluate if staff members with different tenure levels had different perspectives of the profit center. The results showed that longer-tenured employees often had more favorable opinions. The results of the ANOVA showed a significant F-value (p < 0.05), indicating that the organization’s past and employees’ experiences impacted how staff members perceived the profit center.

Discussion

Interpretation of Findings

The study’s results indicate inconsistent staff members ‘awareness of profit center goals. Many responders fall into the middle ground regarding their comprehension, being only somewhat aware. Meanwhile, a significant segment takes full cognizance, clearly comprehending the profit center’s aims. This difference in awareness levels highlights the necessity of using targeted communications technology in the dental clinic.

These findings have two ramifications. First, most of the employees in this intermediate category will emphasize their communications more to clarify profit center goals. This would mean organizing frequent information meetings, developing training materials, or having easily obtainable resources to explain the profit center’s purpose, functions, and duties (Alshekaili et al. 2020, P. 45). These focused communication techniques are crucial in narrowing the knowledge gap and ensuring that regardless of position, employees understand what’s needed to achieve the profit center’s goals. Further, only after they acknowledge that this has been understood by those who claim complete consciousness and self-sufficiency can those who entirely use their abilities as supporters and partners. Using this segment’s findings, one can optimize profit center operations and foster a climate of harmony. The task is to fill in gaps in knowledge and take advantage of pre-existing awareness to improve further the profit center’s effect on the dental facility.

The most startling finding of the study was the staff’s opinion of the profit center, which is a good thing. One significant finding about the smooth incorporation of the profit center into the dental hospital is that harmonious positions cannot be attained without opposing opinions. This optimism is in keeping with the profit center’s role as a pocket to fund the hospital’s broader aims. Several reasons account for the absence of opposing viewpoints. Through effective communication channels, staff members can learn the profit center’s purpose and how it contributes to these goals. Of course, if these contributions contribute to more funding for patient care or more extensive educational programs, they may positively affect staff attitudes (Kola et al. 2021 p. 535). In addition to the profit center’s operations, this optimistic attitude creates a harmonious working environment. If employees view the profit center as an asset instead of a problem, it helps to create cooperation and joint efforts in attaining objectives.

Most respondents gave a solid affirmative, revealing the extent to which the profit center exercises control over day-to-day operations at the dental hospital. It points out to hospital management that workflows and procedures should also be changed as the profit center’s pervasive role begins. The effect is so significant that it influences all aspects of hospital operations and requires a long-term plan to cope with the changes brought about by the profit center. The profit center thus becomes essential, and it is necessary (Stoicea et al. 2019, P. 20). For various departments affected by profit center activities to work together, there must be clear communication channels and cooperative innovations. In addition, the impact assessment points out how one activity in a hospital depends on another. Changes in one area due to profit center initiatives can affect other departments. Therefore, cultivating a culture of cooperation and coordination is an intelligent way to manage this influence. Doing this ensures that various departments collaborate, maximizing the profit center’s beneficial effects while reducing possible drawbacks.

Favorable opinions of the profit center’s influence on patient care are reassuring signs of its alignment with the hospital’s primary objective. Employee recognition of advances in patient care indicates that the profit center is contributing favorably to raising the standard of care provided by the dental hospital. This favorable mood is imperative because patient care is central to healthcare facilities’ missions. The profit center’s capacity to improve patient care is consistent with the overall objectives of delivering top-notch healthcare services. To augment our comprehension, it would be advantageous to examine particular facets of patient care that are impacted by the profit center (Sen-Crowe et al. 2021, P. 56). Examining the subtle ways the profit center enhances patient care enables a more focused and systematic approach. Knowing whether it results in better response times, more accessible access to specialized services, or improvements in available treatment alternatives might offer insightful information. With these insights, hospital administration can improve the profit center’s function and ensure it perfectly aligns with the hospital’s mission to provide the best possible patient care.

Effective administration in the dental hospital requires recognizing and comprehending issues with resource allocation, communication hurdles, and ethical considerations. The frequency of these issues highlights the necessity of proactive and strategic actions to guarantee the profit center’s seamless integration and operation. A major operational bottleneck is that 43.2 % of respondents mentioned resource allocation as one of their top three most complex challenges. The hospital administration can establish better resource allocation procedures (Sen-Crowe et al. 2021, p. 58). This could mean appraising the status quo, identifying redundancies, and establishing more effective procedures. The resource allocation policy ensures that the profit center receives such resources while maintaining overall hospital function.

Twenty-two and a half percent of respondents recognized that communication barriers existed. Through these obstacles, efficient channels of communication must be opened. Communication protocols must be robust, technology can help smooth the flow of information, and a culture of open information exchange should be promoted. Communication at one’s own pace Frequent feedback systems and public discussion platforms can help ensure staff members ‘know-how. This is demonstrated by the 34.5 % of respondents who mentioned ethical matters. These problems can be solved by introducing ethical standards, providing ongoing education in ethics, and establishing decision-making procedures. Ethically based planning protects the profit center (Cyr et al. 2019, p. 5). Another clever method of overcoming these obstacles is bringing staff into decision-making. Staff members ‘experience is essential in identifying operational problems and developing practicable solutions. Establishing joint decision-making platforms makes employees feel taken seriously and lets them know their opinions count, which helps them fall into step with hospital objectives.

The fact that the profit center’s greatest treasure is its trained laborers makes clear how necessary human capital is to its success. This recognition shows how important investing in training and retaining qualified professionals is. This strength can be maintained by offering advancement and training opportunities. The fact that 23.7 % of respondents named effective marketing as a source of strength shows that advertising plays a vital role in gaining popular support for the profit center (Cyr et al. 2019, p.8). Creative marketing can enhance exposure and attract more customers. In other words, it means using a variety of communication channels to emphasize the profit center’s value proposition and demonstrate its role in the hospital.

Another strong point is the patient community’s positive response to solidified patient demand (12.9 %). To sustain and make the most of this need, plans should be made for effective management of patient flow and improvement in services. It is also necessary to explore ways to expand services as fast as possible so that they can keep up with rising demand. This is especially true when, as shown in the 10.1 % of respondents, this is a strength: people have different healthcare needs. Using this strength, service offerings can be checked and adjusted periodically to suit patients ‘changing needs. These recognized strengths are how to optimize the production of the profit center and make it sustainable (Khullar et al. 2020, p. 2123). If such tactics are in place, the profit center can continue to be a vital and dynamic part of the dental hospital. However, using those assets effectively requires long-term planning and evaluation investment in marketing and human resources.

Comparison with Literature

In the case of healthcare profit centers, staff support is also a common trait. For example, employees have an overwhelmingly positive opinion about the profit center’s place within the dental hospital. Studies have found that employees are more committed to and willing to cooperate on projects to obtain short-term profit when they believe it will strengthen the organization’s financials (Dumalanede et al. 2020, P. 211). However, the survey participants’ positive assessments show that the staff has recognized its role in helping to fulfill the hospital’s overall goal.

On the other hand, in contrast to specific studies that emphasize employee resistance or concerns about the incorporation of profit-driven initiatives, the respondents’ lack of unfavorable sentiments is noteworthy. Employees in some healthcare settings could voice concerns about the possibility that financial objectives will take precedence over patient care or moral principles. The observed divergence in this study may be explained by contextual variations, distinctive features of the dental facility, or successful communication tactics employed by hospital administration (McClellan et al. 2020, P. 62). Potential worries may have been reduced by the profit center’s aims being communicated and their consistency with the hospital’s mission, leading to a more positive view among staff members.

The literature highlighting the difficulties in managing profit centers in hospital settings is consistent with the difficulties that staff members have noted, especially those about communication obstacles and resource allocation. Research indicates that allocating resources might pose significant difficulties, necessitating strategic planning to guarantee fair distribution while maximizing financial results. The literature also stresses the importance of communication across departments and between management and employees (McClellan et al. 2020, P. 66). Everyone in the dental hospital is a specialist, and the difficulties encountered in this study mirror established concerns about resource distribution and communication.

Also, employees ‘recognition of ethical concerns is compatible with the literature’s insistence that ethics are essential to profit-center operations. Profit-motivated healthcare projects can sometimes produce ethical dilemmas, and ways of dealing with them must be laid down first (Moro Visconti et al. 2020, p. 2318). These ideas are supported by the findings of this study, which show that employees possess a shared consciousness regarding the moral consequences of profit-center operations.

Recommendations for Improvement

Improved Methods of Communication

Focused outreach endeavors must be carried out to increase employees ‘comprehension of profit-center goals. Results indicate that the degree of staff members ‘awareness is not homogeneous, with most falling into the somewhat aware camp. To deal with this problem, the hospital needs to develop comprehensive communication plans that consider the many positions occupied by staff (Li et al. 2020, P.1802). By regularly providing information about the profit center’s accomplishments, plans, and goals through different communication channels such as meetings, newsletters, and digital platforms, every employee can be guaranteed a basic grasp of the profit center’s objectives. Considering the many different interests and styles of communication among staff groups, a comprehensive approach should be adopted in drafting the communication plan.

Training Programs

Handling resource allocation problems, communication difficulties, and ethical issues requires focused training programs. These programs are to increase the capabilities of staff in handling the complexities of profit center operations. Obstacles can be overcome by training employees on how to deal with ethical issues, communicating effectively, and making data-driven decisions. The hospital should cooperate with specialists in these areas in designing training programs tailored to the needs of different staff positions (Li et al. 2020, P.1806). They can strengthen themselves by allowing staff members to overcome obstacles through training programs. If profit center activities are done this way, they will operate more efficiently overall.

Continuous Feedback Mechanism

Creating a continuous feedback mechanism is vital to learning how the profit center affects daily work, patient care, and new issues. Regular feedback sessions, whether focus groups, questionnaires, or one-to-one encounters, will provide valuable information about the personnel’s experience and attitudes. The hospital needs to establish a channel for receiving direct and honest feedback. Another vital implementation is anonymous feedback methods to ensure employee privacy and encourage open communication (Hung et al. 2019, p. 8). Contributing to continuous improvement initiatives and developing a responsive and adaptable culture will be made possible by evaluating the feedback obtained and implementing practical recommendations.

Collaborative Decision-Making

Including employees in profit center operations decision-making processes is an intelligent way to alleviate worries and encourage participation. By considering the opinions of different staff groups, collaborative decision-making guarantees the development of inclusive and well-informed initiatives. Collaborative decision-making can be facilitated by forming cross-functional committees or task groups with representation from various departments (Sen-Crowe et al. 2021, P. 58). These discussion boards allow employees to voice their opinions, voice concerns, and actively determine the course of profit center operations. Establishing an inclusive culture in decision-making improves decision quality and gives employees a sense of commitment and responsibility.

Limitations of the Study

However, various limitations must be considered when interpreting this study’s results. However, focusing only on one dental clinic inside a public university hospital, the results may not be easily applied to other healthcare environments with different goals and structures. Every healthcare facility has no uniform operating environment, and different facilities have different profit center dynamics. Therefore, care should be taken when generalizing these results to the whole healthcare system.

Another possible limitation is the study’s use of self-reporting and Internet surveys. Participants may give socially acceptable answers or withhold some of their thoughts, which constitutes response bias. When using self-reported data, ensuring the total accuracy and sincerity of answers can be challenging. This constraint can be partially overcome by studying alternative data-gathering methods, such as focus groups or interviews, and then triangulating findings to understand the staff viewpoints better. The cross-sectional method can only capture a partial dynamic of changing views as attitudes and opinions change over time. Longitudinal studies, which track the employee perspective over a long period, could shed new light on how employees’ opinions of profit centers in healthcare organizations evolve. It would increase research and study.

Despite these constraints, the study provides relevant data on dental facility personnel’s attitudes about profit centers. Results may not apply to all cases, but they can be used to compare and research healthcare environments. These issues need cautious interpretation and more research into profit centers’ intricate healthcare relationships. It shows staff opinions on a public university hospital’s dental profit center. Profit centers help identify strengths, influence everyday operations, and receive favorable feedback. The recognized challenges provide opportunities for targeted interventions, and cooperative decision-making combined with continuous improvement may lead to even higher employee satisfaction. The essential aims of the suggestions are to enhance inclusive decision-making, training, feedback systems, and communications. Though suffering its limitations, the study enriches our understanding of profit centers in healthcare environments by revealing that we must develop individual-tailored alternatives to problems encountered and fully involve employees.

Conclusion

Within the dental facility of a public university hospital, a survey to explore staff opinions on integrating and running a profit center was highly informative. The results revealed a high degree of variation–almost everyone was “somewhat aware.” Fortunately, a significant portion entirely agreed, emphasizing the need to devise effective communication strategies so that staff members clearly understand profit center objectives. A significant finding was that every one of the respondents had a positive view of the profit center; not one had an unfavorable opinion. The optimistic approach fits the ideal of a profit center: to make money for the hospital.

With most staff reporting that they were strongly influenced in their daily work, the influence on their duties and responsibilities was enormous. This is yet another expression that the profit center has permeated joint operations. It highlights the value of optimizing procedures and having departments work together. Regarding patient care, the positive opinions suggest that the profit center promotes the hospital’s primary mission, and many employees are willing to admit that patient care has improved. Awareness of difficulties in allocating resources, communication barriers, and ethical considerations suggests embracing strategic interventions to help circumvent or minimize these operational obstacles.

Profit center strengths included high-quality staff, outstanding marketing, a significant patient need, and various offers. These benefits show how human capital affects profit center success and enables performance adjustment. They influence hospital policy and operations. Second, employee awareness improvements indicate more outstanding communication. Through communication, all employees may understand the profit center’s aims. Thus, employees foster unity and vision, improving the workforce.

Effective management addresses ethics, resources, and communications. Hospital workers can learn these abilities through training and data-driven resource allocation. Overcoming profit center operational issues and ethical considerations can assist in building ethical and communication guidelines. The poll found that staff involvement and satisfaction increase total staff satisfaction. Workers’ participation in for-profit centers’ decision-making and input on improvements can boost workplace responsibility and happiness. Positive reviews can assist hospital management in enhancing employee morale and engagement.

Understanding public university hospital profit center staff views demands more than facts. It also helps execute profitable projects. Positive remarks and identified difficulties help hospital administration manage profit centers. These results point to the importance of planning strategy, involving staff in decision-making constantly, and maintaining open communication.

To sum up, profit centers are crucial to public university hospitals. If these institutions can turn good staff attitudes into money, they can succeed financially and generally. Hospital management can create an environment where profit centers match the hospital’s objective, benefiting patients, staff, and hospitals. But it can be done by reducing obstacles, increasing communication, and pointing to what staff have discovered. Hospital administrators trying to squeeze the maximum profit from their profit centers in today’s public university hospital environment will find the report handy. In addition, it represents a starting point for further research.

References

Alshekaili, M., Hassan, W., Al Said, N., Al Sulaimani, F., Jayapal, S.K., Al-Mawali, A., Chan, M.F., Mahadevan, S. and Al-Adawi, S., 2020. Factors associated with mental health outcomes across healthcare settings in Oman during COVID-19: frontline versus non-frontline healthcare workers. BMJ open, 10(10), p.e042030.

Baashar, Y., Alhussian, H., Patel, A., Alkawsi, G., Alzahrani, A.I., Alfarraj, O. and Hayder, G., 2020. Customer relationship management systems (CRMS) in the healthcare environment: A systematic literature review. Computer Standards & Interfaces, 71, p.103442.

Bae, Y.S., Kim, K.H., Choi, S.W., Ko, T., Jeong, C.W., Cho, B., Kim, M.S. and Kang, E., 2020. Information technology–based management of clinically healthy COVID-19 patients: lessons from a living and treatment support center operated by Seoul National University Hospital. Journal of medical Internet research, 22(6), p.e19938.

Borsa, A., Bejarano, G., Ellen, M. and Bruch, J.D., 2023. Evaluating trends in private equity ownership and impacts on health outcomes, costs, and quality: systematic review. bmj, 382.

Cham, T.H., Lim, Y.M. and Sigala, M., 2022. Marketing and social influences, hospital branding, and medical tourists’ behavioral intention: Before‐and after‐service consumption perspective. International Journal of Tourism Research, 24(1), pp.140-157.

Chmielewska, M., Stokwiszewski, J., Filip, J. and Hermanowski, T., 2020. Motivation factors affect medical doctors’ job attitudes and public hospitals’ organizational performance in Warsaw, Poland. BMC Health Services Research, 20, pp.1-12.

Collin, V., O’Selmo, E. and Whitehead, P., 2021. Psychological distress and the perceived impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on U.K. dentists during a national lockdown. British Dental Journal, pp.1-8.

Cyr, M.E., Etchin, A.G., Guthrie, B.J. and Benneyan, J.C., 2019. Access to specialty healthcare in urban versus rural U.S. populations: a systematic literature review. BMC health services research, 19(1), pp.1-17.

Dumalanede, C., Hamza, K. and Payaud, M., 2020. Improving healthcare services access at the bottom of the pyramid: The role of profit and non-profit organizations in Brazil. Society and Business Review, 15(3), pp.211-234.

Hassen, N., Lofters, A., Michael, S., Mall, A., Pinto, A.D. and Rackal, J., 2021. Implementing anti-racism interventions in healthcare settings: a scoping review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(6), p.2993.

Hung, L., Liu, C., Woldum, E., Au-Yeung, A., Berndt, A., Wallsworth, C., Horne, N., Gregorio, M., Mann, J. and Chaudhury, H., 2019. The benefits of and barriers to using a social robot PARO in care settings: a scoping review. BMC geriatrics, 19, pp.1-10.

Islam, M.S., Rahman, K.M., Sun, Y., Qureshi, M.O., Abdi, I., Chughtai, A.A. and Seale, H., 2020. Current knowledge of COVID-19 and infection prevention and control strategies in healthcare settings: A global analysis. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 41(10), pp.1196-1206.

Khullar, D., Bond, A.M. and Schpero, W.L., 2020. COVID-19 and the financial health of U.S. hospitals. Jama, 323(21), pp.2127-2128.

Kola, L., Kohrt, B.A., Hanlon, C., Naslund, J.A., Sikander, S., Balaji, M., Benjet, C., Cheung, E.Y.L., Eaton, J., Gonsalves, P. and Hailemariam, M., 2021. COVID-19 mental health impact and responses in low-income and middle-income countries: reimagining global mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(6), pp.535-550.

Li, X., Krumholz, H.M., Yip, W., Cheng, K.K., De Maeseneer, J., Meng, Q., Mossialos, E., Li, C., Lu, J., Su, M. and Zhang, Q., 2020. Quality of primary health care in China: challenges and recommendations. The Lancet, 395(10239), pp.1802-1812.

Marmo, S. and Berkman, C., 2020. Hospice social workers’ perception of being valued by the interdisciplinary team and the association with job satisfaction. Social work in health care, 59(4), pp.219-235.

McClellan, M.J., Florell, D., Palmer, J. and Kidder, C., 2020. Clinician telehealth attitudes in a rural community mental health center setting. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 44(1), p.62.

Moffat, R.C., Yentes, C.T., Crookston, B.T. and West, J.H., 2021. Patient perceptions about professional dental services during the COVID-19 pandemic. JDR Clinical & Translational Research, 6(1), pp.15-23.

Moro Visconti, R. and Morea, D., 2020. Healthcare digitalization and pay-for-performance incentives in innovative hospital project financing. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(7), p.2318.

Ozretić Došen, Đ., Škare, V., Čerfalvi, V., Benceković, Ž. and Komarac, T., 2020. Assessment of the quality of public hospital healthcare services by using SERVQUAL. Acta Clinica Croatica, 59(2.), pp.285-292.

Patterson Norrie, T., Villarosa, A.R., Kong, A.C., Clark, S., Macdonald, S., Srinivas, R., Anlezark, J. and George, A., 2020. Oral health in residential aged care: Perceptions of nurses and management staff. Nursing Open, 7(2), pp.536-546.

Sen-Crowe, B., Sutherland, M., McKenney, M. and Elkbuli, A., 2021. A Closer Look into global hospital beds capacity and resource shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Surgical Research, 260, pp.56-63.

Seneviratne, C.J., Lau, M.W.J. and Goh, B.T., 2020. The role of dentists in COVID-19 is beyond dentistry: Voluntary medical engagements and future preparedness—frontiers in medicine, 7, p.566.

Stoicea, N., Costa, A., Periel, L., Uribe, A., Weaver, T. and Bergese, S.D., 2019. Current perspectives on the opioid crisis in the U.S. healthcare system: a comprehensive literature review. Medicine, 98(20).

Triantafillou, V., Kopsidas, I., Kyriakousi, A., Zaoutis, T.E. and Szymczak, J.E., 2020. Influence of national culture and context on healthcare workers’ perceptions of infection prevention in Greek neonatal intensive care units. Journal of Hospital Infection, 104(4), pp.552-559.

Zamparas, M., Kapsalis, V.C., Kyriakopoulos, G.L., Aravossis, K.G., Kanteraki, A.E., Vantarakis, A. and Kalavrouziotis, I.K., 2019. Medical waste management and environmental assessment in the Rio University Hospital, Western Greece. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy, 13, p.100163.

write

write