Inflation, as per measurement by the consumer’s price index, reflects the annual percentage of its cost to the average consumer in obtaining a basket of services and goods that may be changed at specific intervals, such as annually (Kauerauf, 2020). The formula used is Laspeyres.

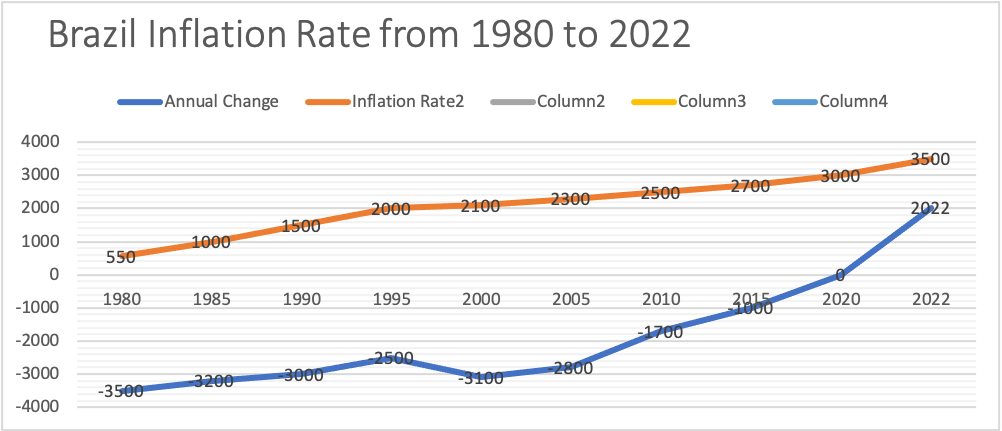

Brazil’s rate of inflation in 2021 was approximately 8.28%, a 5.09 increase from the year 2022

The inflation rate for the year 2020 was projected as 3.22%, a 0.51% decline from 2019

Brazil’s inflation rate for 2019 was 3.70%, a 0.06% increase from 2018

(Devarajan et al., 2022). Brazil’s inflation rate for 2018 was 3.67%, a 0.23% increase from 2017.

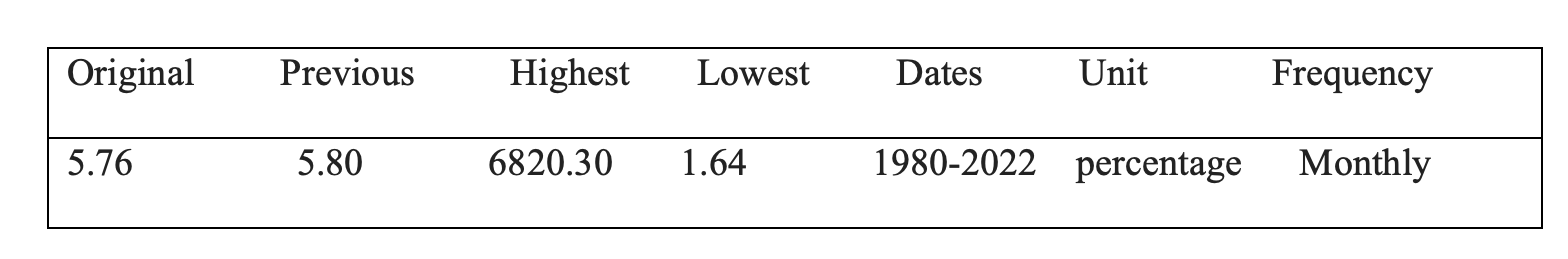

Brazil’s price inflation rate for consumers stood at 5.75 percent year-on-year by the beginning of January 2023; very little had changed from 5.77 percent in the previous month and was slightly lower than the market consensus of about 5.79 percent.

In Brazil, the inflation rate measures a vast rise or drop in prices paid by consumers for a basket of everyday goods. The most critical index categories are Food and beverages (18 percent of total weight); transport(20 percent), housing (16 percent); health care(14 percent); and personal expenses (10 percent). Education constitutes about 7 percent; communication accounts for 3 percent, clothing for 4 percent; and household goods at 5 percent.

Latino-American countries have realized massive economic growth for the past two decades, with an annual expansion rate of about 3%. This economic growth rate resulted from high commodity prices, favorable microeconomic policies, social policies, and innovative and structural reforms. When it comes to incrementing commodity prices, many of the exporters experienced a significant rise in terms of trade, and this is in terms of export prices relative to import prices. The innovative social policies boosted the economic growth rate through the mechanism for analyzing and collecting data for reliable information.

This strategy has been used to evaluate progress and improve programs to ensure that scarce resources are used effectively in handling more pressing issues. On the other hand, microeconomic policies were essential in these countries as they enhanced a high and sustainable growth rate (Franko, 2018). Therefore microeconomic stability was a key consideration as a strategy for reducing poverty. In most instances, the high growth rates are sustainable because microeconomic stability alone does not ensure a high economic growth rate.

The colonization aspect had an enormous impact on the economic expansion of Latino people by the Spanish and Portuguese governments around the 15th century. Through colonization, there was expansion in the trade base, and most of the produce, such as coffee in Brazil, was exported to European countries for consumption, which boosted income. Influence on the cultural change also played a role; women and girls were enrolled in several schools and later contributed to tax payments through employment. In countries such as Chile, Peru, and brazil, effective transport networks were established, which aided in supplies of goods to the market destinations. The colonizers also frequently used these roads (Lloyd & Lee, 2018). Colonization is also a vital aspect of democracy reshaping in the respective states; more Latino Americans Join armies and provide security for the government system and economic stability.

Product-led growth is the latest marketing formula and growth in the SaaS domain. Regarding the latest formula, the customer’s presence is the central driving component together with the know-how (McGowan, 2019). One of the characteristics of Product-led growth is the intensive use of the product in guiding the customer through the process of the sales funnel. In this case, customers have first-hand experience with the product and can convert at their own pace. The second characteristic is that its end goal is based on habit-building in which customers are getting hooked to the product via unique features and the pricing model that are enticing to motivate them to pay for the extra subscription. Thirdly, there are always the desired actions since customers can begin engagement in positive publicity by word of mouth upon testing the freemium model. Lastly, its methodology is focused on the customer and is product-driven from the beginning to the end.

From the perspective of approach, the product-led growth in Latina America has formed the heat of economic development as many low-income consumers can test the product and promote it based on their financial capabilities even amidst the economic crisis. There have also been heated arguments on product dependence or development in Latino America. However, the end goal has been to relate the capacity of product-led growth to generate dynamic growth (McDowell, 2022). The desired action for product-led growth in Latino America has been centered on product interest, and this desire has always remained. This is because the product exports continue to make these countries enjoy the largest share of the export basket, thus earning much foreign exchange on the methodology based on the customer focus and product-driven. The state-led industrialization was poised to strike a compromise between dependence on domestic markets for protection or the enhancement of Latino America’s world trade share.

Both the structuralism school of thought and theory of dependency developed out of the critique of the available paradigms of development; with this can of interpretation, the researchers and authors argued concerning the possibilities of not being able to uncover apart from just dealing with the problems facing the Latin Americans of development and underdevelopment (Dvoskin & Feldman, 2018). Structuralism argues in favor of a development policy that is directed inward. This argument is steered towards import-substituting industrialization, and dependency theory support the new economic international order and one of its strands. In other words, dependency theory interprets a transition to socialism as a means of eradicating the state of underdevelopment.

Both theories still need to be explored in this assignment; their relevance based on the contemporary has been clogged by insufficient knowledge and is often subjected to constant misplaced criticism (Bruff & Starnes, 2020). The facts drawn from these two schools of the theory are that while economic growth and exports have been improved, this has not been adequate for a significant reduction in extreme income disparities or poverty levels. However, poverty has been wholly reduced from its peak levels of the decades lost in the 1980s. Given the fall of the socialist East European system, countries like China were able to transition the market economy from just mere structural plans and the implementation of sound economic policies that favored the vast population. Latin American countries ought to have been oriented to a market-driven economy that favors many people instead of few (Ormaechea, 2020). In the context of Neoliberalism, Latin America has recorded social and economic development. There are always two ways in which Neoliberalism is widely used, a slight usage that is described as a shift in policies subset to some extent more significant reliance on markets, and a massive usage that implies the fundamental change in state and policy relationship. The first incidence was witnessed in most regions in the 1980s and 1990s.

Migrating to market dependence was essential, annoying relative to the advocate’s expectations, and absolutely as a strategy for development. The stability effect, growth, and inequality depend on other factors, including social institutions, structural policies, asset distribution, and politics (Wiarda & Kline, 2018). The critical assessment of the view of Neoliberalism is challenging to comprehend. States of Latin America has experienced different checked history concerning citizens. The concept has never been appropriate since it has had an unequal impact, especially in social provisioning. In most cases, its impact at the same time has been very oppressive to the rights of citizens.

A broader view of neoliberal in the context of radical retreat to a small state is detrimental to development. However, in several instances, such a prism approach is not a valuable strategy for analyzing the most recent experiences; there has been a significant import-substitution shift model, but this has never included the entire retreat of the state. Therefore, it is critical to suggest that this analytical approach and development practice could be of better essence.

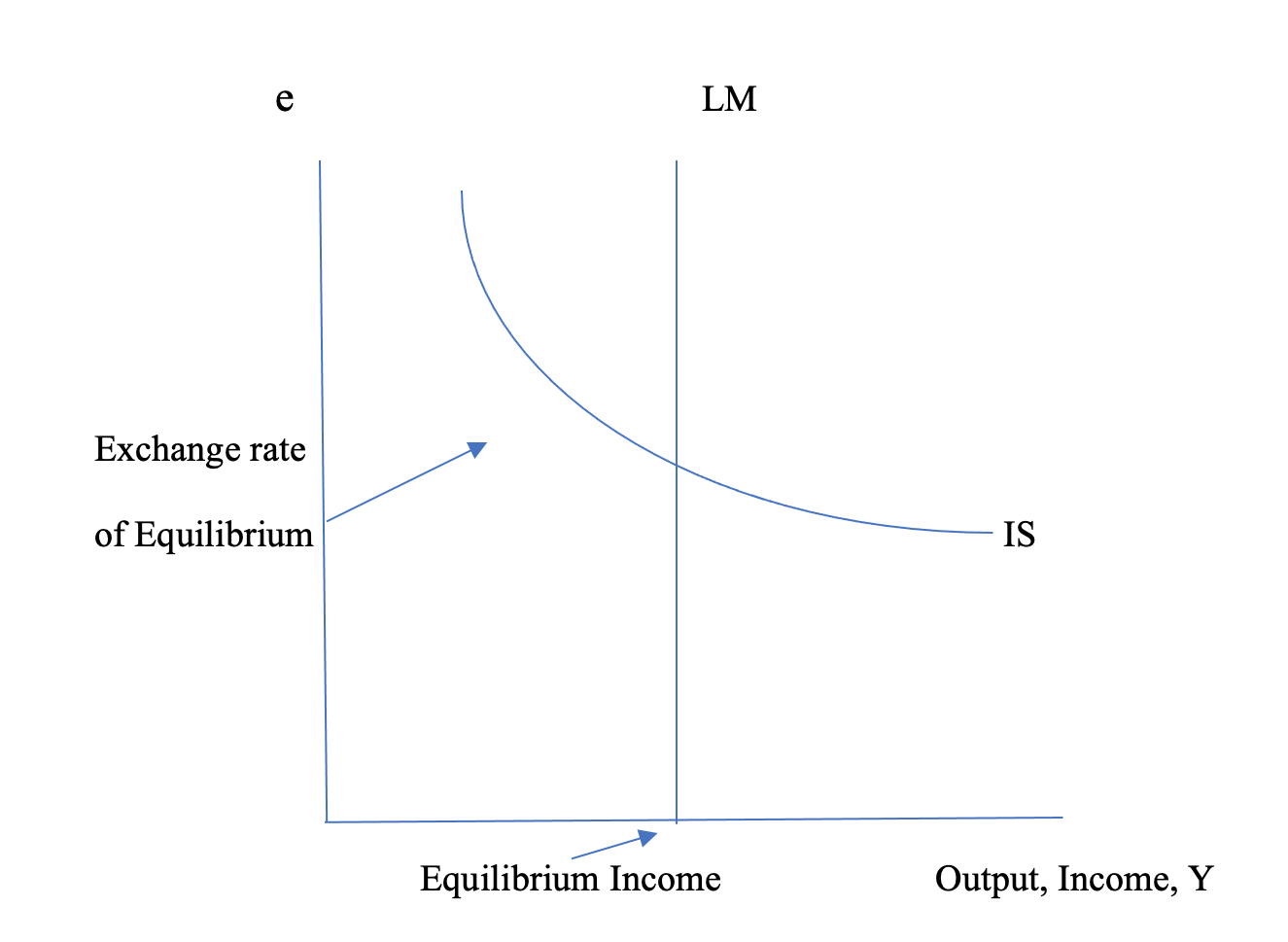

Mundell-Fleming Model explores the open economy in which finances and trade are added. The assumption of IS-LM is that of a closed economy.

An increase in consumers’ confidence about the future tends to boost the consumer’s desire to spend more with little savings. When there is an increment in government expenditure, the IS curve will shift to the right. This behavior means that the general domestic interest rate and GDP will increase. The effect will trigger consumers to stretch their pockets and spend more on essential commodities (Rapetti & Frenkel, 2018). However, an increment in interest rates will attract foreign investment to take advantage of exorbitant rates. The currency strengthening means that it will be more expensive for customers dealing with domestic producers to buy the exports in the home country. Therefore there will be a decline in net export, which will cancel out the spending by the government and shift the curve IS to the left.

(b) During the ISI on the restriction of trade by the government, the Mundell-Fleming model, with the view of the domestic rate of interest determined by the interest rate of the world, the government tends to focus on the role played by the exchange rate in short run national income determination (Born et al., 2019). The Mundell-Fleming model enables the government to predict economic behavior depending on whether it adopts a fixed exchange rate or flexible rates.

There are numerous reasons why that are historic why Latin America did not experience ISI right after or at the time of the European ISIs. The colonial policies provided by European countries yield much of the explanation for the previous two cases; on the other hand, the social-economic structural aspect aids in explaining the case of Latin America (Lubbock, 2022). The availability of lucrative markets that are external for the primary exports within the region, which profited the elites, means there was the minimal political desire to alter the economic structures. In the early twentieth century, countries in Latin America needed to have entrepreneurial classes, market size, or labor force. Therefore ISI strategy could have helped in solving the developmental problems within countries in Latin America, such as Brazil. This is because the European powers needed more leverage towards government enforcement through free trade policy maintenance, thus blocking the effect of ISI possibilities.

Latin America was full of processing and manufacturing activities prior to the occurrence of world war I. Currently, and it is comprehensively documented that in the late 19th century (Lucchini, 2021). Small factories and workshops in food products and textiles industries had expanded some of the development of some of Argentina, Mexico, Brazil, and other countries within Latin America. The presence of machine tools and spare part workshops immensely contributed to the development of sugar refining mills and the service railroads. There was even an attempt to raise the tariffs to protect the industries that were incipient to stimulate the development of the modern one. Such attempts were not geared towards uplifting the lives of ordinary people in these countries; instead, they were meant to propel the financial status of the capitalist, the main shareholder in both import and export substitution industries.

References

Born, B., D’Ascanio, F., Müller, G. J., & Pfeifer, J. (2019). The Worst of Both Worlds: Fiscal Policy and Fixed Exchange Rates.

Bruff, I., & Starnes, K. (2020). Framing the Neoliberal Canon: Resisting the market myth via Literary Enquiry. In Authoritarian Neoliberalism (pp. 13-27). Routledge.

Devarajan, S., Go, D. S., Robinson, S., & Thierfelder, K. (2022). How Carbon Tariffs and Climate Clubs can Slow Global Warming. Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper, (22-14).

Dvoskin, A., & Feldman, G. D. (2018). Income Distribution and the Balance of Payments: a Formal Reconstruction of Some Argentinian Structuralism Contributions Part II: Financial Dependency: Part II: Financial Dependency. Review of Keynesian Economics, 6(3), 369-386.

Franko, P. (2018). The puzzle of Latin American Economic Development. Rowman & Littlefield.

Kauerauf, M. (2020). International Trade and Economic Growth: an Exploratory Case Study Based on the Country Analysis of Colombia, South Africa and Vietnam (Doctoral dissertation).

Lloyd, P., & Lee, C. (2018). A review of the Recent Literature on the Institutional Economics Analysis of the Long‐run Performance of Nations. Journal of Economic Surveys, 32(1), 1–22.

Lubbock, R. (2022). Capitalist Geopolitics and Latin America’s Long Road to Regionalism. Globalizations, 19(4), 536–554.

Lucchini, G. (2021). From Financial to Climate Debt: Changing Patterns of Political Economy in Latin America.

McDowell, E. L. (2022). From Transaction to Enaction: Reframing Theatre Marketing (Doctoral dissertation, University of Leeds).

McGowan, D. (2019). Animated Personalities: Cartoon Characters and Stardom in American Theatrical Shorts. The University of Texas Press.

Ormaechea, E. (2020). Latin American Development: What About the State, Conflict, and Power? Journal of Economic Issues, 54(2), 322–328.

Rapetti, M., & Frenkel, R. (2018). A Concise History of Exchange Rate Regimes in Latin America. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Editora.

Wiarda, H. J., & Kline, H. F. (2018). A concise Introduction to Latin American politics and Development. Routledge.

write

write