Part 1: Personal Narrative

The Uruk Era, which corresponds to a period in ancient Mesopotamian history that began around 5000 years ago, is known for being the pinnacle of Uruk’s power. I was born into a family living in Uruk, an ancient city-state in Mesopotamia, in 3000 BCE. This region was known by Greek historians as Mesopotamia, or “the land between the rivers.” These rivers, which ran from the Taurus Mountains in Anatolia (now Turkey) in the north all the way down to the Persian Gulf, were the Euphrates to the west and the Tigris to the east (Bertman, 2005). Growing up in Uruk, religion was very significant and heavily influenced the people’s culture, with many temples and monuments dedicated to gods and goddesses. Waking up every day, I would walk the streets of Uruk, hearing the chantings of the priests and the chatter of the people as they went about their day. At the centre of the city, there was a great temple dedicated to the goddess Inanna (Harmansah, 2007).

Every day I would watch in awe as the priests and priestesses prepared the offerings for the goddess. I believed that the gods and goddesses were watching over and taking care of us, and it was comforting to have that belief. I had the privilege of living in a time of great advancement for our city. We had developed a system of writing that was used to keep records of transactions. We also developed a system of irrigation that allowed us to cultivate the land and sustain our population. The city was bustling with activity, with people from all walks of life, from merchants to craftsmen to farmers. People from neighbouring cities would come to Uruk, bringing with them new ideas and goods. This allowed me to learn about the cultures of other cities and to compare and contrast them with our own. It was not always easy living in Uruk. I lived in fear of the gods and goddesses, and I was constantly worried that I would anger them in some way. I also had to deal with the dangers of living in an ancient city, such as rampant disease and famine. Nevertheless, despite the risks, I was filled with a sense of hope, believing that if I lived a good life, the gods and goddesses would reward me.

Living in Uruk gave me an appreciation for the culture of the ancient world and for the people who lived and worked in it. I was filled with admiration for the craftsmanship and the ingenuity of the people of Uruk, who, despite their limited resources, created great monuments and structures that still stand today. My life in Uruk was a unique and special experience, one that will stay with me for the rest of my life. I am thankful for having been given the opportunity to live in a time and place as beautiful and rich in culture as Uruk. I often reflect on my day and think about the changes that are taking place in Uruk. I am filled with a sense of wonder, as I know that our city is playing a significant role in the development of civilization. At the same time, I am also filled with a sense of fear, as I know that the future of Uruk is uncertain. Our city is constantly growing and changing, and I never know what tomorrow will bring.

PART 2

The city of Uruk is most known as the birthplace of writing, famous for its King Gilgamesh and a number of other cultural innovations, such as the development of cuneiform script around 3200 BCE. The remains of Uruk can still be found today in Warka, Iraq. The contemporary name of Iraq is believed to have originated from Uruk (Bogdanovych et al.,2012.p.28). Due to resource depletion and the loss of its position as a political and commercial power, Uruk was abandoned around 300 CE. Uruk, located in present-day Iraq, is one of the oldest cities in the world. The city is situated 250 km south of Baghdad, on an ancient branch of the Euphrates River known as Erech (now Warka). Uruk was the first major city founded in Sumer in the 5th century B.C. and is considered one of the largest Sumerian settlements and most important religious centres in Mesopotamia(Crüsemann et al.,2019). The city was continuously inhabited from around 5000 BC up to the 5th century A.D. Uruk was one of the world’s earliest cities and was a major centre of trade and power in the ancient Near East. Evidence of daily life in Uruk can be found in archaeological remains, written records, and artistic depictions(Algaze, 2013,p.92). This evidence reveals a highly stratified society with a complex social, political, and economic organization.

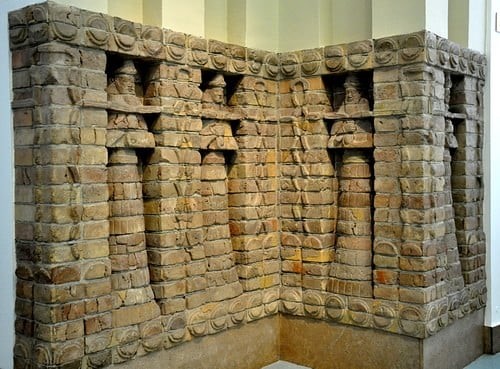

Over the centuries, Uruk has remained a significant centre of culture and commerce, leaving behind an impressive legacy of archaeological remains. The city was divided into the Eanna District and the older Anu District, named for and dedicated to the goddess Inanna and her grandfather-god Anu, respectively(Crüsemann et al.,2019). The famous Mask of Warka (also known as `The Lady of Uruk’), a sculpted marble female face found at Uruk, is considered a likeness of Inanna and was most likely part of a larger work from one of the temples in her district.

Furthermore, we can turn to the city’s art and architecture to understand Uruk’s cultural life. The city’s temple complexes contain some of the earliest examples of figurative art in Mesopotamia in the form of reliefs depicting gods, kings, and scenes from mythology. These reliefs provide a glimpse into the beliefs and values of the city’s inhabitants. Meanwhile, the city’s walls feature various decorative motifs, such as bulls and lions, which may have been symbols of power and protection(Algaze, 2013,p.93).

As Cuneiform texts indicate, Gilgamesh, the King of the city’s first dynasty, was said to have built the city walls in 4700 BC(Nissen, 1986.p.320). The Eanna (house of An) temple complex was also built in the city, dedicated to the goddess Inanna (also known as Ishtar, goddess of love, procreation, and war). The Greeks and Romans adopted her worship under the name of Aphrodite or Venus. Uruk is renowned for its religious and scientific importance. Thousands of clay tablets have been excavated from the city, dating back to the beginning of writing around 5000 years ago(Bogdanovich et al.,2012). Mesopotamia is the world’s first city because excavations have revealed a series of very important structures and deposits of the 4th millennium B.C.

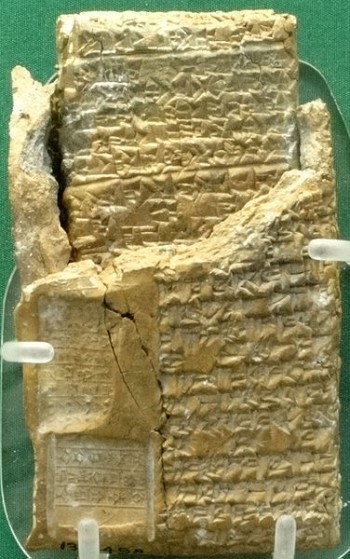

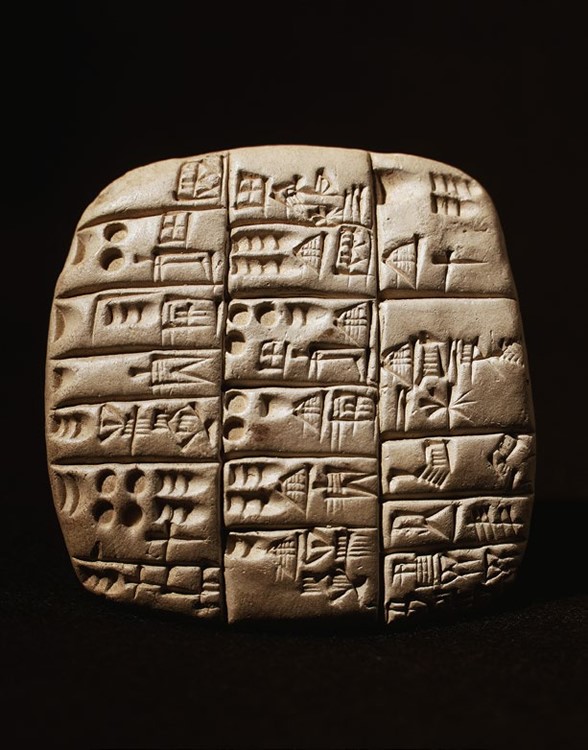

The two major temple complexes in Uruk are the Anu (god of the sky) sanctuary and the Eanna sanctuary, which is dedicated to Ishtar and is known as the Mosaic Temple of Uruk. The city also boasts a Ziggurat, which was built by Ur-Nammu of Ur in the Ur III period (late 3rd millennium B.C.) (Bertman, 2005). Uruk is also famous for its contribution to writing, as evidence from the excavations of the Eanna sanctuary shows the development of writing from simple pictographic symbols to the Cuneiform script of the Early Dynastic period(Crüsemann et al.,2019). These mud-based tablets were often enclosed in clay envelopes and signed with cylinder seals. These seals’ tiny images employ a system of symbolic representation that indicates the owner’s political rank.

The clay tablets keep track of economic activities such as the administration of people, land, animals, and agricultural products—often in vast numbers. Contrary to Egypt, the marks carved into Mesopotamian clay evolved into increasingly abstract, wedge-shaped, or cuneiform symbols; by 2600 BC, scribes employed them to record Sumerian poetry and literature(Nissen, 1986.p.318). For instance, the documents show that Uruk was home to a wide variety of people, including priests, merchants, artisans, and labourers. They also provide evidence of the city’s taxation and legal systems, as well as its trade networks(Crüsemann et al.,2019).

The archaeological remains of Uruk are some of the most important sources of evidence for daily life in the city. The most significant remains are the city walls and temples, which were constructed in the fourth millennium BCE. These monuments served to both protect the city and to legitimize the power of the ruling class. The walls and temples reveal the complexity of Uruk’s political and religious systems, which were organized around the cult of the goddess Inanna(Bogdanovych et al.,2012.p.30). The archaeological remains also include various artefacts, including pottery and stone vessels, which were used for food storage and preparation. Other artefacts include weapons, tools, and jewellery, which were used for hunting and trading that have been unearthed from the city’s ruins(Bertman, 2005). Uruk was a bustling centre of trade, and archaeological evidence suggests that the city was home to a wide variety of craftspeople and merchants. These artefacts show us that Uruk was a centre of production and exchange and that the city’s inhabitants were highly skilled in various trades.

In addition, there are many artistic depictions of daily life in Uruk, which include scenes of hunting and warfare, religious ceremonies, and the production of goods. Written records like administrative documents, such as legal contracts and accounts of economic transactions, provide further evidence of daily life in the city. There are also literary texts that describe the city’s history and culture, as well as religious texts that explain the beliefs and practices of the people of Uruk(Nissen, 1986.p.320). The city was divided into social classes and governed by a powerful ruling class, revealing a complex and stratified society.

The ruins of Uruk are currently located several kilometres east of the Euphrates River in southern Iraq, in a featureless, arid desert(Bogdanovich et al.,2012.p.28). However, 5,000 years ago, it was encircled by reed marshes, rich alluvial soil, and streams that provided access to nearby towns and the Persian Gulf. Uruk remained an important city for the various civilizations that ruled Mesopotamia, such as the Akkadians, Assyrians, Achaemenids, and Seleucids. The city was ultimately abandoned about the 2nd century A.D.

Bibliography

Algaze, G., (2013). The end of prehistory and the Uruk period. In The Sumerian World (pp. 92–118). Routledge. https://www.worldhistory.org/books/0812210476/

Bertman, S., (2005). Handbook to life in ancient Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press. https://www.worldhistory.org/books/0195183649/

Bogdanovych, A., Ijaz, K. and Simoff, S., 2012. The city of Uruk: teaching ancient history in a virtual world. In Intelligent Virtual Agents: 12th International Conference, IVA 2012, Santa Cruz, CA, USA, September 12-14, 2012. Proceedings 12 (pp. 28-35). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-33197-8_3

Crüsemann, N., van Ess, M., Hilgert, M., Salje, B. and Potts, T. eds., 2019. Uruk: First City of the Ancient World. Getty Publications. https://books.google.co.ke/books?hl=en&lr=&id=muCvDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=city+of+uruk+%22ancient+history%22&ots=RCHomiKXT8&sig=4CnkSwcbRljTlj5VySjQ-_Y4PLM&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=city%20of%20uruk%20%22ancient%20history%22&f=false

Harmansah, Ö., 2007. The Archaeology of Mesopotamia: Ceremonial centres, urbanization and state formation in Southern Mesopotamia. Retrieved 2011-08-28

Nissen, H.J., 1986. The archaic texts from Uruk. World Archaeology, 17(3), pp.317–334.

List of Figures

Fig 1: Cuneiform tablet still in its clay case: a legal case from Niqmepuh, King of Iamhad(Allepo),1720BCE(British Museum)

Fig 2: The Inanna’s Temple at Uruk

Fig 3: Detail of a cuneiform tablet from Tello in southern Mesopotamia.

Fig 4: The Uruk or Warka Vase is an ancient artefact depicting a religious banquet and likely an agricultural festival. It is composed of four registers which likely represent the social hierarchy of Uruk. The bottom register shows water, plants, and ears of wheat; the second shows right-facing sheep; the third shows nude priests with offering vessels; and the fourth and top register shows a “priest-king” (damaged) and attendant approaching the goddess Inanna, who can be identified by the two reed gateposts leading into her temple filled with offerings.

Fig 5: Beveled rim bowls were a common type of clay bowl produced in large quantities during the 4th millennium B.C. in the Uruk culture of Mesopotamia. They make up the majority of ceramic artefacts found at Uruk sites and are thus a reliable marker of the Uruk presence in the area.

write

write