Introduction

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) concerns are taken into account by financial sector investors in order to make greater long-term investments into environmentally friendly economic activities and projects. For example, the preservation of biodiversity, pollution avoidance, and the circular economy are all examples of environmental factors that may be included in a comprehensive environmental policy. Inequality, inclusion, labour relations, investments in human capital and communities, and human rights challenges are a few examples of social factors. Management structures, employee relations and executive compensation all play a critical part in making sure that social and environmental factors are taken into account when making decisions (Deutschmann, 2020).

Policy and action must be taken by governments throughout the globe to incentivise sustainable investment and development via a set of laws and behaviours that have a beneficial impact on companies, the economy and eventually the lives of their population (Deutschmann, 2020). It’s becoming clearer that financial centres may play an important role in identifying the path to long-term prosperity. Financial services that include conservation, social and supremacy criteria for investment or company decisions for the long-term benefit of both customers and the social order are known as sustainable financial services (SFS).

New conditions call for money-related governance structures to play a critical role in spurring financial progress and maintaining ability estimates that depend on progress from various angles, such as expanded natural duty, atmospheric versatility and low carbon emissions; human rights; gender equity; manageable financial growth; and social integration. Based on a long-term insurgency over worldwide financial growth and on full-scale financial alternatives illustrated by legal, inventive, and government norms, the budgetary administration framework was built (Dávid & Kovács, 2019). It’s crucial to evaluate the financial, social, and administrative aspects in order to ensure that the system’s goals in environmental change, reducing disparity, reducing ozone-depleting substance outflows, and improving vitality adequacy and social consideration are met.

Giving too much long-term aggressiveness and steady growth, upgrading low impact enterprises based on asset safeguarding, reusability, reusing and sustainable power sources and considering the needs of who and what is to come are the supportability aims. There must be dynamic inclusion of all actors in the financial value chain, from the well-known and professional speculators to financial go-betweens, accounting organizations as well as rating offices across the globe. Financial choices are critical in company since many of the actions and elements that contribute to corporate failure may be addressed with an effective decision-making process in the form of adequate strategy and financial management. The organization’s long-term development and goals are aided by the company’s superior decision-making (Dávid & Kovács, 2019).

Corporate failures are blamed on a variety of factors, including a lack of financial planning, a lack of moral leadership, restrictions on subsidy access, a lack of assets, an abnormal trajectory of advancement, a lack of vital and monetary expectations, an inefficient allocation of fixed resources, and poor management (Budzik-Nowodzińska, 2020). It’s possible to change both the organization’s appearance and the way it’s run by focusing on financial decisions and major value drivers, such as capital expenditures, operational capital management and productivity and resource returns. Fixed resource and capital planning interest is particularly important when considering financial prospects.

The reasons for long-term development and influence make certain decisions more crucial than others. Despite the need of enhancing the decision-making process by modifying financial strategies to link sustainable challenges with monetary verdicts and essential value drivers, there is a lack of progress in this area. The new organizations are concentrating on the evaluation of decision making and its impact on the competitiveness of small businesses. Business success depends heavily on how well organizations use their limited resources; especially young enterprises, which must be very efficient in order to survive and earn money. Different frameworks and tactics are used by the new organizations to measure, report and evaluate financial capital in order to improve decision-making with the use of reporting to drive change and include performance management and give value to stakeholders (Budzik-Nowodzińska, 2020).

This paper seeks to dig deep into sustainability in finance and decision making based on the banking industry around the world and specifically in Indonesia. The section of this paper reviews a number of studies and theories regarding sustainable decision making and environment-responsible ways of raising finance. The theories and key terms defined in the 2nd section are further applied in section 3 based on real data from the industry of interest. Section 4 links sections 2 and 3 before making a conclusion in section 5. All in all, the objective of this paper is to define how companies can raise finance with environment responsible and sustainable decision making.

Literature Review

Because of the tremendous changes taking place in today’s financial markets, firms are under immense pressure to both survive and retain their success in the future. Because of the increasing relevance of business sustainability to investors, businesses, and consumers alike, there has been a significant increase in interest in the issue in recent years. New organizations are growing in scope, fusing money-related, natural, and social maintainability through manageability, as well as fiscal and economic development, with thin and transitory budgetary objectives. Because of the availability of resources and long-term financial development, organizations that care about the environment and the well-being of the general population have become a need rather than a choice. Corporate maintainability procedures are geared at broadening the scope of the money-related primary concern to include environmental and cultural variables of authoritative execution, as well as improving the feasibility of reasonable budgetary development (Migliorelli & Dessertine, 2017).

Socially Responsible Investment

It has been many years since socially responsible investing (SRI) was first used as an investment strategy. The notion of socially responsible investing (SRI) and the criteria used to evaluate responsible investments have evolved throughout time. The selection of these criteria has changed throughout time, but the criteria that have remained constant are those that represent modern norms and values that are now recognized in society. SRI has been characterized as “the process of incorporating personal beliefs and social issues into investment decision-making processes.” This definition, on the other hand, is much too broad, since it raises the issue of how much social responsibility is regarded to be sufficient social responsibility. An even more specific description is provided by Eurosif and the Principles for Responsible Investment.

SRI is defined as “an approach to investing that aims to incorporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors into investment decisions, in order to better manage risk and generate sustainable, long-term returns” according to the Principles for Responsible Investment, which are supported by the United Nations. According to the Eurosif organization, SRI is described as “a long-term focused investing methodology that incorporates environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues into the research, analysis, and selection process of securities within an investment portfolio.” Fundamental analysis and involvement are combined with an assessment of ESG variables in order to maximize long-term returns for investors while also benefiting society by influencing the behaviour of corporations.” The notion of corporate social responsibility serves as the foundation for the ESG criteria used in investment evaluation (CSR). Contemporary theoretical understanding predicts the presence of a link between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the economic success of a firm, as well as the resulting influence on the decision-making of investors in the future.

According to research findings by Sandberg (2018), firms with a favourable image of sustainability have beneficial impacts in their relationships with investors, are more readily able to get funding, and have higher market capitalizations. This occurs as a result of investors’ perceptions of sustainable businesses as being less risky. The findings of more than investigations were summarized by Sandberg (2018) who discovered that about percent of studies reveal a non-negative association between ESG and financial success, with the vast majority of studies reporting positive outcomes. Companies with strong environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance, according to the International Finance Corporation of the World Bank, have an advantage because they decrease costs and risks, boost their brand, and increase their development, hence delivering extra value to investors.

According to Volz (2018, p.11), “the following areas are most often covered by ESG criteria: Energy usage and consumption, water consumption and trash generation are all environmental factors to consider. – Environmental criteria to consider include: management systems; climate change; pollution control; land remediation; and the environmental effect of goods. The social criteria are as follows: respect for human rights, cultural diversity, labour practices, involvement in the community, charity contributions, and product safety – Corporate governance requirements include the following: code of conduct, board structure, board independence, audit committee independence, remuneration, bribery, and disclosure.”

The word “sustainable investment” may be used to refer to a variety of different types of investments, including responsible investment, ethical investment, and so-called impact investing. Compared to conventional investors, socially responsible investors put a higher focus on the moral component of their investments, and research has shown that they do not have to forego income or take on more risk. Generally speaking, sustainable investment has an influence on society and the environment in addition to resulting in increased economic performance. A number of previous research have focused on the differences in risks and returns between sustainable and conventional investing strategies (Stoian & Iorgulescu, 2020).

There may be a variety of factors that influence an investor’s decision to invest in a sustainable manner, the most important of which is the use of a broader range of criteria for investment decisions, which allows investors to avoid risks that affect long-term investment returns but are not detectable through financial analysis. Scandals in corporate practice have also played a role in this development. There is also pressure from the EU, which views it as a suitable instrument for investors, and from a variety of other groups of stakeholders, who all contribute to this decision (Ryszawska, 2018).

Green Finance

The economy is threatened by climate change and other environmental issues. Money dangers will become more obvious in the future years and decades. A wide variety of assets, including food and farming, infrastructure, house construction, and insurance, will be adversely affected by the expected rise in sea levels and the increased frequency and severity of severe weather events in the time it takes today’s young people to reach retirement age. As the globe implements the Paris Agreement, sectors and corporations who do not make a timely transition to low-carbon may potentially face expensive regulatory or legal action. Climate change and other sustainability concerns are still ignored by many financial institutions, corporations, and regulators, despite this. The financial markets will be able to function more effectively and UK institutions and investors will be better positioned to profit from the low-carbon transition if these risks and possibilities are properly recognized and disclosed (Flammer, 2020).

Long-term problems such as environmental sustainability and anthropogenic global warming risks and possibilities are frequently sacrificed in the UK’s investment chain as a result of institutional incentives that promote a focus on short-term gains. Furthermore, ambiguity regarding the degree to which pension trustees must examine and mitigate climate-related risks may deter institutional investors from taking action to solve climate-related concerns. The results of our own investigation of the largest pension funds in the United Kingdom (those with assets above £ billion) present a mixed picture of the sector. According to some, the concept that climate change is essentially a matter of ethics or business responsibility rather than a significant material danger to current and future value has become obsolete (Flammer, 2020).

Corporations and pension funds must examine environmental threats in the context of their fiduciary responsibility in order to sustain long-term value. More opportunities for people to participate in choices about where their retirement savings are invested, as well as more openness, are necessary. According to recent polls, many millennials desire their money invested in ways that do not depend on fossil fuels for income generation. Those who wish to express themselves should have more opportunities. Human scepticism grew as they learned that pension fund trustees and other governing organizations are not required to consult with beneficiaries when developing their Statement of Investment Principles (SIP) (Flammer, 2020). Furthermore, once the SIP has been completed, there is no need to notify the beneficiaries of its existence or completion. The government should require fiduciaries to communicate with their beneficiaries when creating SIPs to guarantee that their interests are being represented. Efforts to enhance financial reporting on sustainability are gaining traction in a number of countries throughout the globe. The government claims that it has pushed publicly listed companies to adopt international regulations on climate-related financial reporting (Kurznack et al., 2021).

Ministers, on the other hand, seem to have made no concrete measures in this direction. People who have a pension fund should make sure that climate risk reporting is applied equally to asset owners (such as pension funds) and their investment managers, rather than only publicly listed corporations, as the government has proposed. It is critical that these organizations be given some breathing room in order to improve the way they report on climate-related threats and opportunities. A voluntary technique, on the other hand, is unlikely to be beneficial in the short run. It is suggested that the government impose obligatory reporting on a “compliance or explain” basis. Climate-related risk reporting may and should be examined within the current framework of financial law and regulation in the United Kingdom. As a result, the government should give guidelines, pointing out that the Firms Act already compels corporations to report climate change risks that are financially significant to the government (Schoenmaker, 2020).

The Financial Conduct Authority should alter the Corporate Governance Code of the Financial Reporting Council and the United Kingdom Stewardship Code to compel climate-related financial disclosure on a “comply or explain” basis (FCA). It may be possible to include climate risk reporting within existing corporate governance and reporting standards in the United Kingdom, eliminating the need for new law. The government should examine the results at least a year after they have been implemented. For example, if regulators do not fully apply the Article and increase their capability to oversee climate risk management, the government should create a new sustainability reporting legislation similar to that of France. The existing financial regulatory structure in the United Kingdom is insufficient to deal with the problem of climate change. Only the Bank of England and its Prudential Regulation Authority have given the matter the attention it requires in the United Kingdom. The current cycle of climate change adaptation reporting mandated by the Climate Change Act provides another big opportunity for other regulatory bodies to include climate change risk management into their work (Tang & Zhang, 2020).

Bankruptcy and sustainable development

Insolvency is a legal term used to describe a situation when a firm is unable to meet its financial obligations. For example, profitability, liquidity ratios and solvency have been taken into account in recent research to anticipate business bankruptcy and sustainable development. To ensure long-term growth, it is critical to examine the range of feasible growth rates. Predicting whether or not a new company will file for bankruptcy is one of the most important issues to investigate in the field of corporate finance (Dávid & Kovács, 2019). Corporations in the 21st century are seen as rising economies when developing a model for predicting bankruptcy. Predicting bankruptcy by using financial ratios supplied in financial statements, and these financial statements are used to analyse business circumstances in terms of financial sustainability viewpoint (Sandberg, 2018).

Sustainable growth, on the other hand, is growth that a corporation can sustain forever without meeting difficulties or raising concerns. Fast-growing enterprises may find it challenging to get the funding they need to expand. As a result, emerging businesses should exercise caution when generating long-term growth estimates. To characterize the practice of integrating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) problems into investment choices, many terminologies such as sustainable investing, socially responsible investing (SRI), impact investing, moral investing, and others are used interchangeably. A rising number of institutional investors and other market participants are showing an interest in these aspects of the market. Despite the fact that various investors take varied approaches to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) aspects, institutional investors employ a wide range of tools, databases, and procedures to include ESG considerations into their decision-making (Ryszawska, 2018).

Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations are being incorporated into institutional investors’ investment decisions in a variety of ways. The significance of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors is discussed, as well as the significant problems and possibilities that investors face when making investment choices based on them. These findings may be useful to institutional investors in developing adequate ESG governance structures and processes. The COVID-19 quandary also highlights the need for more strong portfolios that address a larger range of concerns, as shown by the European Union. Previous OECD work on regulatory frameworks for institutional investors in various jurisdictions has found that environmental, social, and governance concerns in investment decisions are generally permissible if they are related to insurance companies’ and pension funds’ financial obligations to their beneficiaries and members, as well as their own financial obligations (OECD, 2017).

Because ESG integration is a continuous process, investors may want to approach it in phases. The first stage in implementing ESG concerns is to analyze environmental, social, and governance problems from a risk perspective and determine how each ESG aspect may affect financial performance. In the second phase, it is critical to consider environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals while deciding between two equivalent assets. During the third phase of their ESG journey, “advanced” institutional investors should set goals or objectives in terms of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) consequences. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs), the Paris Agreement, and other efforts are often cited as sources of inspiration for these goals (United Nations, 2020).

Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) aspects may be seen primarily as a risk factor by institutional investors. Risk management should be expanded to incorporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) problems in addition to financial ones in order to optimize risk-adjusted financial returns. According to the World Economic Forum, certain institutional investors may incorporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations into their general risk prevention and mitigation, while others may incorporate ESG variables into conventional analysis when assessing the risks associated with individual investments. When making a real estate investment choice, real estate investors should consider ESG concerns such as a property’s location, as mentioned below. Acceptance of a larger set of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria is often seen as the next stage in the evolution of investors. According to recent research, some insurance firms that previously incorporated key ESG criteria in their overall investing process are now adding ESG-themed funds, bonds, and other impact investments to their portfolios (Redclift, 2015).

A increasing number of institutional investors are incorporating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors into their whole decision-making process and investment choices. This policy may have been necessitated by a strategic choice made by the investor or the organization. A big insurer, for example, has an environmental, social, and governance plan as well as a climate strategy, all of which are used in the investment process, according to a group policy. In our nation, positive change is seen as a powerful tool, and investment is regarded as an essential component of it. When asset management is assigned to a third party, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors may also come into play. Compliance with the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment is a requirement for certain institutional investors that contract with external asset managers (UN PRI). Other investors examine an asset manager’s environmental, social, and corporate governance policies and processes before choosing an asset manager. They will continue to do so in the future (Redclift, 2015).

Impact investments are typically seen to be a more “advanced” approach to environmental, social, and governance concerns than other kinds of investing. Investors concerned with climate change mitigation may place a higher value on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) characteristics associated with these aims. They may apply this weighting to particular funds they manage or to all of their managed assets, depending on their needs. A new product that invests in chosen climate-focused assets will be introduced in 2020 by a Danish pension fund that has been integrating responsibility and sustainability themes into its investment choices for many years. This product’s long-term performance is projected to be impacted by the provider’s “conventional” pension systems. According to the fund’s management, returns on this fund are likely to be more volatile and fluctuating in the short term due to the fund’s unique attention and investing policy features (Migliorelli, 2017).

Data and Results

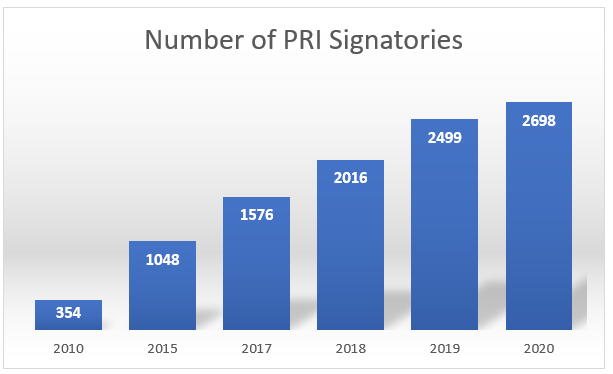

As a result of the integration of economics, society, and environment in twenty-first-century development, green economy and green finance have been driving forces in contemporary economic growth. This notion is larger than the concept of sustainable development. In order to transform a carbon-intensive economy into a long-term green economy, low-carbon green development has been the objective of global environmental governance since the UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties in Copenhagen in December 2015. Ecologically aware financing lays more emphasis on the relationship between human life and nature than traditional finance. Corporate investment in sustainable financial methods and decision-making has increased significantly since 2015. This is shown by a trend in the number of PRI signatories globally.

For example, in their October 2018 progress report on climate-related concerns, NGFS members agreed that “financial risks” are connected to environmental changes, indicating a significant relationship between green finance and changes in environmental circumstances. As a result of their efforts to protect the environment, corporations have shifted their attention to environmental sustainability. It says that financial institutions, society, and the environment must collaborate to produce long-term, sustainable development for society as a whole. A green bond, as a green financial product, provides both economic and environmental advantages. This research investigates these benefits as well as the possibilities of future expansion.

To put it another way, the green financial system is an institutional arrangement that employs financial instruments such as green credit, green bonds, sustainable stock indices and related products, as well as sustainable development funds, sustainable insurance, and carbon finance, as well as relevant policy incentives, to aid in the economic green transformation. Green bonds have become more popular as a financial product in recent years. Following a period of substantial expansion in 2013, the global green bond market has risen even faster since 2013. Green bond issuance increased by $36.593 billion in 2014, compared to $11.042 billion in 2013. Between 2007 and 2014, these values were used to underpin about 80% of all green bonds issued.

The global issuance of green bonds continued to surge in the first three months of 2019, hitting $47.2 billion, the greatest amount ever recorded for the first three months of any year. Furthermore, China’s Green Bond market is rapidly expanding. Since the issuance of the country’s first green bond at the end of 2015, the country has surged to the top of the worldwide rankings. According to the Climate Bonds Initiative, the worldwide issuance of green bonds reached $167.3 billion in 2018. China contributed $18.8 billion of this total, ranking second only to the United States in terms of contribution.

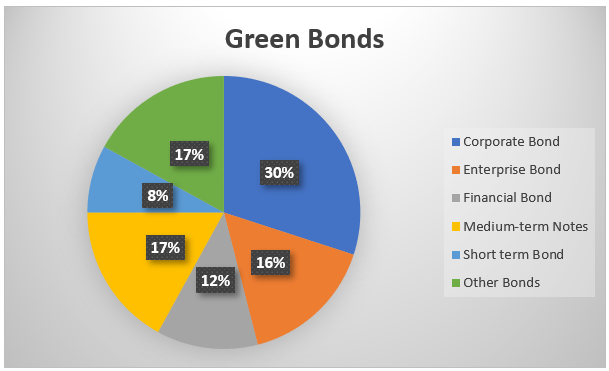

At the present, investors, researchers, and academics are all interested in environmentally friendly bonds. Scholars have started to investigate the definitions and criteria, the issuance and pricing, as well as the dangers and advantages associated with green bonds. While green bonds are becoming more popular as an innovative green financing tool in many nations, whether they can really express their intrinsic vitality is debatable. Green bonds are issued in conjunction with green industrial enterprises and environmental development initiatives that seek to mitigate the impacts of climate change, save resources, and limit pollution. In the banking sector in Indonesia, the distribution of bonds is as shown in the pie-chart below. The diversification among the bonds helps in risks mitigation.

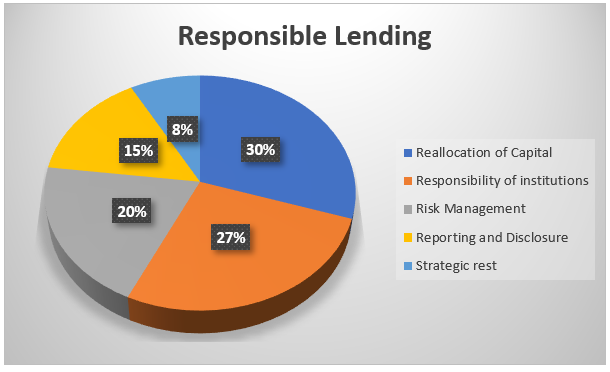

Whether green bonds can provide environmental benefits while still providing a reasonable return on investment is a subject that has to be addressed. Even while some studies have examined the economic and environmental benefits of green bonds, their results have been limited to the performance of particular companies and have failed to take into account the impact of green bonds on corporate social responsibility. Alternatively, institutions, especially those in the financial industry have resulted to promote responsible borrowing among their customers. For example, banks in Indonesia have adopted a number of strategies that help them in lending management. A study conducted by Carè et al. (2018) revealed that the banks employ a combination of debt management strategies to help shield them against financial risks. These strategies are summarized in the pie-chart below;

Discussion

According to the findings of the OECD ESG survey, almost all respondents agreed that excluding or avoiding ESG concerns is frequently the first step toward ESG integration. Diluting one’s assets is another common tactic among institutional investors. Companies having links to contentious topics, such as weapons, coal, and cigarettes, are the most often requested for exclusion and divestment. Investment in fossil fuel exploration and production, alcohol, gambling, unbalanced boards of directors, and pornography are some of the sectors that financial institutions and investors often neglect.

In the first stage of exclusion, exclusionary screening and best-in-class investment are heavily used to determine whether or not a candidate is suitable for further consideration. Many considerations must be considered when selecting assets for inclusion in a portfolio, including the E, S, and G criterion. The following table contains a list of these requirements: Criteria E, S, and G A rating system or scale is used to assess the performance of different assets as well as their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) ratings, which may be developed internally or externally. To make a final asset selection, choose those businesses that score higher than average, those that score higher than a predefined threshold, or those that get the top ratings in each of the asset categories. …. (Schoenmaker, 2020).

Depending on the circumstances, the best-in-class strategy may be used to a wide range of sectors and specific ESG objectives. According to many investors, one of the best methods to invest in carbon-heavy industries is to examine the company’s carbon footprint and only invest in enterprises with a low or greatly reduced carbon footprint. Although not all institutional investors use these tactics, many have adopted features of ESG-integration initiatives such as active ownership and involvement. Although the G20/OECD Principles urge fiduciaries to be actively involved in their firms, the G20/OECD Principles note that not all institutional investors are ready to participate as active shareholders, and making engagement mandatory may be counterproductive (Paranque, 2016).

Investors who want to become active shareholders must follow the G20/OECD Principles for Active Shareholders, which give guidance for investors. This document contains principles for disclosing voting policies and decision-making procedures, as well as for managing and disclosing any conflicts of interest and other problems (OECD 2011). OECD (2015) (Schoenmaker, 2020). Some of the behaviors connected with active ownership may be forbidden by rules, so institutional investors should be aware of this. Colombia and Costa Rica, for example, prohibit pension funds from attending shareholder meetings.

Institutional investors that want to execute an active ownership and engagement approach in their assets may want to explore voting in person. A technique like this would need a significant investment of time and money, which is why proxy voting is most often utilized in most instances. A growing trend in the financial services industry is the collaboration of certain institutional investors and third-party service providers to build voting and participation mechanisms that are shared by all stakeholders (Stoian & Iorgulescu, 2020). Stoian and Iorgulescu (2020).

If the corporation refuses to respond to their engagement strategies, institutional investors may choose to sell their shares. It may also be necessary to implement divestment in the event of an ESG-related event, such as a natural catastrophe, that is expected to have a negative impact on the company’s performance. According to a statement made by a Danish pension fund in 2020, the mining corporation had been prohibited and its assets had been auctioned off owing to the company’s refusal to respond to their repeated attempts at communication and engagement on concerns relating to the new tailings dam.

Institutional investors often employ thematic ESG focus to attain these objectives. Speculative investments in thematic assets are often directed toward assets that generate both predictable financial returns and a positive environmental impact. This category includes sustainable and social bonds, as well as microfinance funds (Tang & Zhang, 2020).

Conclusion

It is determined that financial choices play a vital role in company since they influence a variety of organizational activities and elements that contribute to corporate failure. Business may be managed via the use of an effective decision-making process, which can take the shape of sound business plans and sound financial administration. Excellent decision-making contributes to the organization’s ability to achieve long-term development and achieve its strategic goals. Several factors are cited as the primary reasons for the failure of business: a lack of financial development, unethical decision-making, and limited access to capital; a lack of investment; abnormal growth; a lack of tactical and fiscal planning; and an excess of fixed asset administration and capital management.

It is possible to improve the performance of the company as well as the decision-making process by linking sustainable concerns to monetary decisions and critical value drivers, such as capital planning and capital cost, working capital administration, and profitability and asset revenues, among other things. When it comes to financial choices, the investment in fixed assets and the preparation of capital budgets are particularly important. Because of the reasons for long-term growth and consequence, these decision-making processes are comparably more crucial. Despite the necessity of improving the decision-making process via the adaptation of financial strategies that link sustainable concerns with monetary verdicts and essential value drivers, there is a need to improve the decision-making process through the adaptation of financial strategies.

In addition to assisting in the development of pressure points that prompt firms to form and invest in sustainability plans, long-term risks and possibilities are also being considered. The risks and opportunities associated with long-term sustainability are rising, and management, investors, regulators, and lenders are paying more attention to them. Sustainable hazards are threatening mining activities in the new companies, with risks associated to the point of view of overconsumption of water, while reputational risks of the organizations are intertwined with investment in projects that may have potentially harmful environmental results.

References

Budzik-Nowodzińska, I. (2020). Sustainable management of commercial real estate in the context of investment performance. Finance and Sustainability, 61-75. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34401-6_6

Carè, R., Trotta, A., & Rizzello, A. (2018). An alternative finance approach for a more sustainable financial system. Palgrave Studies in Sustainable Business In Association with Future Earth, 17-63. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66387-6_2

Deutschmann, C. (2020). Entrepreneurship, finance and social stratification. The Routledge International Handbook of Financialization, 31-42. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315142876-3

Dávid, S., & Kovács, L. (2019). The development of clearing services – Paradigm shift. Economy & finance, 6(3), 296-310. https://doi.org/10.33908/ef.2019.3.4

Flammer, C. (2020). Green bonds: Effectiveness and implications for public policy. Environmental and Energy Policy and the Economy, 1, 95-128. https://doi.org/10.1086/706794

Kurznack, L., Schoenmaker, D., & Schramade, W. (2021). A model of long-term value creation. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2021.1920231

Migliorelli, M., & Dessertine, P. (2017). Time for new financing instruments? A market-oriented framework to finance environmentally friendly practices in EU agriculture. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 8(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2017.1376270

Paranque, B. (2016). A provisional conclusion: A shift towards finance as a Commons? Critical Studies on Corporate Responsibility, Governance and Sustainability, 387-394. https://doi.org/10.1108/s2043-905920160000010036

Redclift, M. (2015). Routledge international handbook of sustainable development. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203785300

Ryszawska, B. (2016). Sustainability transition needs sustainable finance. Copernican Journal of Finance & Accounting, 5(1), 185. https://doi.org/10.12775/cjfa.2016.011

Ryszawska, B. (2018). Sustainable finance: Paradigm shift. Finance and Sustainability, 219-231. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92228-7_19

Sandberg, J. (2018). Toward a theory of sustainable finance. Palgrave Studies in Sustainable Business In Association with Future Earth, 329-346. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66387-6_12

Schoenmaker, D. (2018). A framework for sustainable finance. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3125351

Schoenmaker, D. (2020). Sustainable finance. Essential Concepts of Global Environmental Governance, 253-254. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367816681-103

Stoian, A., & Iorgulescu, F. (2020). Sustainable finance. Finance and Sustainable Development, 6-20. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003011132-2

Tang, D. Y., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Do shareholders benefit from green bonds? Journal of Corporate Finance, 61, 101427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2018.12.001

Volz, U. (2018). Fostering green finance for sustainable development in Asia. Routledge Handbook of Banking and Finance in Asia, 488-504. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315543222-27

write

write